from Leslie's Monthly

The Adventure of the Fifth Street Church

by Ellis Parker Butler

After that Glaubus affair I did not see Perkins for nearly a year. He was spending his money somewhere, but I knew he would turn up when it was gone, and one day he entered my office, hard up but enthusiastic.

"Ah," I said, as soon as I saw the glow in his eyes, "you have another good thing? Am I in it?"

"In it?" he cried. "Of course, you're in it. Does Perkins of Portland ever forget his friend? Never! Sooner will the public forget that 'Pratt's Hats Air the Hair' as made immortal by Perkins the Great! Sooner will the world forget that 'Dill's Pills Cure All Ills,' as taught by Perkins!"

"Is it a very good thing, this time?" I asked.

"Good thing?" he asked. "Say! Is the soul a good thing? Is a man's right hand a good thing? You know it! Well, then, Perkins has fathomed the soul of the great U. S. A. He has studied the American man. He has watched the American woman. He has discovered the mighty lever that heaves this glorious nation onward in its triumphant course."

"I know," I said, "you are going to start a correspondence school of some sort."

Perkins sniffed contemptuously.

"Wait!" he cried, imperiously. "See the old world crumbling to decay! See the U. S. A. flying to the front in a gold painted horseless bandwagon! Why? Why does America triumph? What is the cause and symbol of her success? What is mightier than the sword, than the pen, than the Gatling gun? What is it that is in every hand in America; that opens the good things of the world for rich and poor; for young and old, for one and all?"

"The ballot box?" I ventured.

Perkins took something from his trousers' pocket and waved it in the air. I saw it glitter in the sunlight before he threw it on my desk. I picked it up and examined it. Then I looked at Perkins.

"Perkins," I said, "this is a can-opener."

He stood with folded arms and nodded his head slowly.

"Can-opener, yes!" he said. "Wealth opener; progress-opener." He put one hand behind his ear and glanced at the ceiling. "Listen!" he said. "What do you hear? From Portland, Maine, to Portland, Oregon; from the palms of Florida to the pines of Alaska -- cans! Tin cans! Tin cans being opened!"

He looked down at me and smiled.

"The backyards of Massachusetts are full of old tin cans," he exclaimed. "The garbage wagons of New York are crowned with old tin cans; the plains of Texas are dotted with old tin cans. The towns and cities of America are full of stores, and the stores are full of cans. The tin can rules America! Take away the tin can and America sinks to the level of Europe! Why has not Europe sunk clear out of sight? Because America sends canned stuff to their hungry hordes!"

He leaned forward and, taking the can-opener from my hand, stood it upright against my inkstand. Then he stood back and waved his hand at it.

"Behold!" he cried. "The emblem of American genius!"

"Well," I said, "what are you going to sell, cans or can-openers?"

He leaned over me and whispered:-

"Neither, my boy. We are going to give can-openers away, free gratis!"

"They ought to go well at that price," I suggested.

"One nickel-plated Perkins Can-opener free with every can of our goods. At all grocers," said Perkins, ignoring my remark.

"Well, then," I said, for I caught his idea, "what are we going to put in the cans?"

"What do people put in cans now?" asked Perkins.

I thought for a moment.

"Oh!" I said, "tomatoes, and peaches, and corn, sardines, and salmon, and --"

"Yes!" Perkins broke in, "and codfish, and cod-liver oil, and kerosene oil, and cotton-seed oil, and axle grease and pie! Everything! But what don't they put in cans?"

I couldn't think of a thing. I told Perkins so. He smiled and made a large circle in the air with his right forefinger.

"Cheese!" he said. "Did you ever see a canned cheese?"

I tried to remember that I had, but I couldn't. I remembered potted cheese, in nice little stone pots, and in pretty little glass pots.

Perkins sneered.

"Yes?" he said; "and how did you open it?"

"The lids unscrewed," I said,

Perkins waved away the little stone pots and the little glass pots.

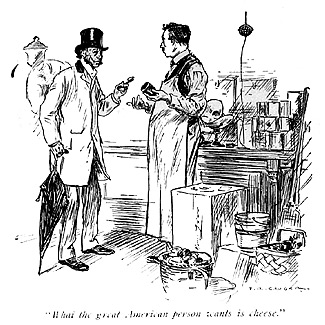

"No good!" he cried. "They don't appeal to the great American person. I see," he said, screwing up one eye -- "I see the great American person. It has a nickel-plated, patent Perkins Can-opener in its hand. It goes into its grocer's shop. It asks for cheese. The grocer shows it plain cheese by the slice. No, sir! He shows it potted cheese. No, sir! What the great American person wants is cheese that has to be opened with a can-opener. Good cheese, in patent, germ-proof, airtight, watertight, skipper-tight cans, with a label in eight colors. Full cream, full weight, full cans; picture of a nice, clean cow and red-cheeked dairy-maid in short skirts on front of the label and eight recipes for welsh rabbits on the back."

He paused to let this soak into me, and then continued:--

"Individual cheese! Why make cheese the size of a dishpan? Because grandpa did? Why not make them small? Perkins' Reliable Full Cream Cheese, just the right size for family use, twenty-five cents a can, with a nickel-plated Perkins Can-opener free with each can. At all grocers?"

That was the beginning of the Fifth Street Church, as you shall see.

We bought a tract of land well outside of Chicago, and to make it sound well on our labels we named it Cloverdale. This was Perkins' idea. He wanted a name that would harmonize with the clean cow and the rosy milkmaid on our label.

We owned our own cows, and built our own dairy and cheese factory and made first-class cheese. As each cheese was just the right size to fit in a can, and as the rind would protect the cheese anyway, it was not important to have very durable cans, so we used a can that was all cardboard, except the top and bottom. Perkins insisted on having the top and bottom of tin, so that the purchaser could have something to open with a can-opener, and he was right. It appealed to the public.

The Perkins cheese made a hit, or at least the Perkins advertising matter did. We boomed it by all the legitimate means, in magazines, newspapers and streetcars and on billboards and kites, and we got out a very small individual can for restaurant and hotel use. It got to be the fashion to have the waiter bring in a can of Perkins' cheese and show the diner that it had not been tampered with, and then open it in the diner's sight.

We ran our sales up to six hundred thousand cases the first year, and equaled that in the first quarter of the next year, and then the cheese trust came along and bought us out for a cool eight hundred thousand, and all they wanted was the good will and trademark. They had a factory in Wisconsin that could make the cheese more economically. So we were left with the Cloverdale land on our hands and Perkins decided to make a suburb of it.

Perkins' idea was to make Cloverdale a refined and aristocratic suburb; something high-toned and exclusive, with Queen Anne villas and no fences; and he was particularly strong on having an ennobling religions atmosphere about it. He said an ennobling religious atmosphere was the best kind of a card to draw to -- that the worse a man was, the more anxious he was to get his wife and children settled in the neighborhood of an ennobling religious atmosphere.

So we had a map of Cloverdale drawn, with wide streets running one way and wide avenues crossing the streets at right angles, and our old cheese factory in a big square in the center of the town. It was a beautiful map, but Perkins said it lacked the ennobling religious atmosphere, so the first thing he did was to mark in a few churches. He began at the lower left-hand corner and marked in a church at the corner of First Street and First Avenue, and put another at the corner of Second Street and Second Avenue, and so on right up the map. This made a beautiful diagonal row of churches from the upper right hand comer to the lower left hand corner of the map, and did not miss a street. Perkins pointed out the advertising value of the arrangement -- "Cloverdale, the Ideal Home Site. A Church on Every Street. Ennobling Religious Atmosphere. Lots on Easy Payments."

The old cheese factory was to be the Cloverdale clubhouse, and we set to work at once to remodel it. We had the stalls knocked out of the cow shed and made it into a bowling alley, and added a few cupolas and verandas to the factory, and had the latest styles of wallpaper put on the walls, and in a few days we had a first-class club house.

But we did not stop there. Perkins was bound that Cloverdale should be first-class in every respect, and it was a pleasure to see him marking in public institutions. Every few minutes he would think of a new one and jot it down on the map, and every time he jotted down an opera house, or a school house, or a public library, he would raise the price of the lots, until we had the place so exclusive I began to fear I couldn't afford to live there. Then he put in a streetcar line and a water and gas system, and quit, for he had the map so full of things that he could not put in another one without making it look mussy.

One thing Perkins insisted on was that there should be no factories. He said it would be a little paradise right in Cook County. He liked the phrase "Paradise Within Twenty Minutes of the Chicago Post Office" so well that he raised the price of the lots another ten dollars all around.

Then we began to advertise. We did not wait to build the churches nor the schoolhouse nor any of the public institutions. We did not even wait to have the streets surveyed. What was the use of having twenty or thirty streets and avenues paved when the only inhabitants were Perkins and I and the old lady who took care of the clubhouse? Why should we rush ourselves to death to build a schoolhouse when the only person in Cloverdale with children was the said old lady? And she had only one child, and he was forty-eight years old and in the Philippines.

We began to push Cloverdale hard. There wasn't an advertising scheme that Perkins did not know, and he used them all. People would open their morning mail and a circular would tell them that Cloverdale had an ennobling religious atmosphere. Their morning paper thrust a view of the Cloverdale clubhouse on them. As they rode downtown in the streetcars they read that Cloverdale was refined and exclusive. The billboards announced that Cloverdale lots were sold on the easy payment plan. The magazines asked them why they paid rent when Cloverdale land was to be had for little more than the asking. Round trip tickets from Chicago to Cloverdale were furnished any one who wanted to look at the lots. Occasionally we had a free, open-air, vaudeville entertainment.

Our advertising campaign made a big hit. There were a few visitors who kicked because we did not serve beer with the free lunches we gave, but Perkins was unyielding on that point. Cloverdale was to be a temperance town and he held that it would be inconsistent to give free beer. But the trump card was our guarantee that the lots would advance twenty per cent, within twelve months. We could do that well enough, for we made the price ourselves, but it made a fine impression, and the lots began to sell like hot cakes.

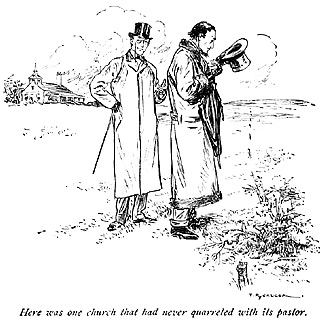

There were ten streets in Cloverdale (on paper) and ten avenues (also on paper), and Perkins used to walk up and down them (not on the paper, but between the stakes that showed their future location) and admire the town of Cloverdale as it was to be. He would stand in front of the plot of weeds that was the site of the opera house and get all enrapt and enthusiastic just thinking how fine that opera house would be some day, and then he would imagine he was on our streetcar line going down to the library. But the thing Perkins liked best was to go to church. Whenever he passed one of the corner lots that we had set aside for a church he would take off his hat and look sober, as a man ought when he has suddenly run into an ennobling religious atmosphere.

One day a man came out from Chicago and, after looking over our ground, told us he wanted to take ten lots, but none suited him but the ten facing on First Avenue at the corner of First Street. Perkins tried to argue him into taking some other lots, but he wouldn't. Perkins and I talked it over, and as the man wanted to build ten houses, we decided to sell him the lots. We thought a town ought to have a few houses, and so far Cloverdale had nothing but the clubhouse. As we had previously sold all the other lots on First Street, we had no place on that street to put the First Street Church, so Perkins rubbed it off the map and marked it at the corner of First Avenue and Fifth Street.

The next day a man came down who wanted a site for a grocery. We were glad to see him, for every-first class town ought to have a grocery, but Perkins balked when he insisted on having the lot at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Sixth Street that we had set aside for the First Methodist Church. Perkins said he would never feel quite himself again if he had to think that he had been taking off his hat to a grocery every time he passed that lot. It would lower his self-respect. I was afraid we were going to lose the grocer to save Perkins' self-respect. Then we saw we could move the church to the corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifth Street.

When we once got those churches on the move there seemed to be no stopping. We doubled the price, but still people wanted those lots, and in the end they got them, and as soon as we sold out a church lot we moved the church up to Fifth Street, and in a bit Perkins got enthusiastic over the idea and moved the rest of the churches there on his own accord. He said it would be a great "ad" -- a street of churches; and it would concentrate the ennobling religious atmosphere and make it more powerful.

All this time the lots continued to sell beyond our expectations, and by the end of the year we had advanced the price of lots one hundred per cent, and were considering another advance. We did not think it fair to the sweltering Chicago public to advance the price without giving it a chance to get the advantage of our fresh air and pure water at the old price, so we told them of the contemplated rise. We let them know it by means of billboards and newspapers and circular letters and magazines, and a great many people gladly availed themselves of our thoughtfulness and our guarantee that we would advance the price twenty per cent, on the first day of June.

So many, in fact, bought lots before the advance that we had none left to advance. Perkins came to me one morning, with tears in his eyes, and explained that we had made a promise and could not keep it. We had agreed to advance the lots twenty per cent, and we had nothing to advance.

"Well, Perky," I said, "it is no use crying. What is done is done. Are you sure there are no lots left?"

"William," he said seriously, "we think a great deal of these churches, don't we?

"Yes!" I exclaimed. "We do!

We think an ennobling religious atmosphere --"

But he cut me short.

"William," he said, "do you know what we are doing? We talk about our ennobling religious atmosphere, but we are standing in the path of progress. A mighty wave of reform is sweeping through Christendom. The new religious atmosphere is wiping out the old religious atmosphere. I can feel it. Brotherly love is knocking out the sects. Shall Cloverdale cling to the old, or shall it stand as the leader in the movement for a reunited church?"

I clasped Perkins' hand.

"A tabernacle!" I cried.

"Right!" exclaimed Perkins. "Why ten conflicting churches? Why not one grand meeting place -- all faiths -- no creeds! Bring the people closer together -- spread an ennobling religious atmosphere that is worth talking about!"

"Perkins," I said, "what you have done for religion will not be forgotten."

He waved my praise away airily.

"I have buyers," he said, "for the nine church lots at the advanced price."

Considering that the land practically cost us nothing, we made one hundred and six thousand dollars on the Cloverdale deal. Perkins and I were out that way lately and there is still nothing on the land but the clubhouse, which needs paint and new glass in the windows. When we reached the Fifth Street Church we paused and Perkins took off his hat. It was a noble instinct, for here was one church that never quarreled with its pastor, to which all creeds were welcome, and that had no mortgage.

"Some of these days," said Perkins, "we will build the tabernacle. We will come out and carry on our great work of uniting the sects. We will build a city here, surrounded by an ennobling religious atmosphere -- a refined, exclusive city. The time is almost ripe. By the time these lot holders pay another tax assessment they will be sick enough. We can get the lots for almost nothing."