from Cosmopolitan

Something for the Kid

by Ellis Parker Butler

After all, Christmas is for the children, dear little things! Half the joy of the day is in seeing them dancing around the Christmas tree, clapping their hands at the pretty lights, and bursting into squeals of joy as they discover their little presents. How easily they are satisfied, the little darlings of today! There has been a great improvement in children since you and I were boys and girls.

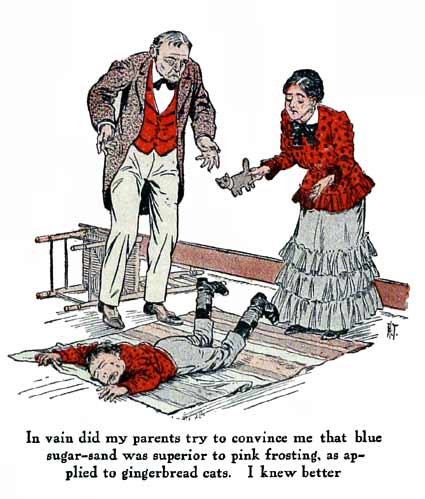

I remember how difficult I was to please, when I was a boy. I remember how I threw myself flat on the floor and howled with rage because I had set my heart on a gingerbread cat with pink fur of frosting, and when I dug the cat out of my stocking it had blue sugar-sand fur. In vain did my parents try to convince me that blue sugar-sand was far superior to pink frosting, as applied to cats. I knew better. My howls spoiled the day for the whole family. I must have been a little wretch. There my parents had gone to all the trouble of preparing a first-class gingerbread cat -- that looked like almost any animal in the zoo, and was consequently universally useful -- and I rewarded their love by howling like a banshee.

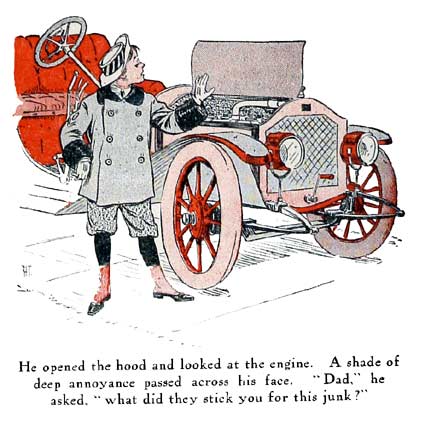

How different it is with the children of today. No more crying over gingerbread cats! Little Mortimer, next door to us, had one of those severe disappointments last Christmas, but he did not drop on the floor and howl. Not at all. He walked around the automobile that his father had given him -- they had the Christmas tree in the side yard, because an automobile is too large to take into the house -- and kicked the tires to see if they were properly inflated. He examined the upholstery of the car, took a brief look at the magneto, the lamps, all the trimmings. All he said was, "Pretty punk!" No howling. No fit of rage. He merely walked around the car, with one hand in his pocket, and repeated in a low, disgusted tone: "Pretty punk! Pretty punk!" Then he opened the hood and looked at the engine. A shade of deep annoyance passed across his face.

"Doesn't little Morty like the pretty automobile Santa Claus has brought him?" his mother asked anxiously.

"Well, all I've got to say," said Mortimer, "is that if I have to drive a four-cylinder machine when everyone is driving a six, the other kids will have the laugh on me." Then he turned to his father. "Dad," he asked, "what did they stick you for this junk?"

His father blushed with shame. Who would not? For a year he and Mortimer's mother had been saving their dollars, vainly hoping that stocks would rise and they could get a high-class French car for Mortimer, but stocks fell instead, and ten hundred dollars was the most they could raise by putting a second mortgage on the house.

"Fourteen hundred and fifty, all complete," said Mortimer's father with a shamed face.

Mortimer smiled grimly. "Stung!" he said.

No howling, you see! No tears!

"My son," said his father, "I know how bitter your disappointment must be, but your mother and I have strained every resource to purchase this little gift. We know it is utterly inadequate to your merits. We -- we hoped," he wiped a tear from his eye, "it would do as a makeshift for a while. If all goes well we mean to give you a six-cylinder imported car on your ninth birthday. You see," he said, and his eagerness was almost pathetic, "we only want to make you happy. On your birthday you shall have a six-cylinder car, Mortimer!"

I want you to observe that there were no yells of uncontrolled rage. No spasms of ill temper. Mortimer merely shrugged his shoulders.

"Oh, hot air!" he said. "Nothing but hot air! You ought to buy a balloon to put that in!"

His father took the rebuke meekly, as he should.

"Mortimer is such a dear boy," his mother said, when she and Mortimer's father had gone into the house. "Did you see how grateful he was, Edgar? I remember what a rage I was in, when I was his age and I had expected a pair of school shoes from Santa Claus, and he only brought me a hair-ribbon. Mortimer has such a sweet disposition!"

"He certainly is a dear chap," said his father heartily, and then he sighed. "I wish to thunder I had something I could mortgage. When a boy receives a fourteen-hundred-and-fifty-dollar car in such a spirit, my heart aches to reward him by giving him a 1911 French limousine. But I'm mortgaged to the limit."

"Well, never mind, dear," said his wife consolingly. "If we give him a better car on his birthday, we can make up his disappointment to him next Christmas by giving him a biplane and an aerodome to keep it in."

Nearly all children are that way, nowadays. That is the wonder of it. They expect automobiles, or aeroplanes, or player-pianos, or ermine stoles, or diamond-studded watches; and yet they do not howl if the biplane turns out to be a mere monoplane, or the watch is studded with only fifty diamonds instead of one hundred. A little word or two of disgust -- that is all. Perhaps a brief suggestion that father and mother have low taste, a prompt request for permission to exchange the gift for something really decent. But no howling. Oh, the world has advanced!

Your own children have improved it that way, have they? Little rascals, expecting Santa Claus to bring gold chains and rubber-tired pony-carts and all sorts of things that were as distant from your thoughts when you were a child as the moon is now! Positively, the Christmas rapacity of the little wretches is getting beyond endurance. Four-year-olds wanting gifts beyond anything the Queen of Sheba carried to King Solomon! What is the matter with the modern child, anyway? Whence this sophistication?

Why, my dear mister and madam, it comes from you and me. Don't blame little Mortimer or little Susie. The children are at heart as sweet and as easily satisfied as you and I were, but we pile gifts on them, and heap gifts on them, and smother good old Santa Claus, with his gingerbread cat, under heaps of silk and gold. Bless your heart, we have made of Christmas a mere occasion for showing off before our little ones, bragging with big gifts.