from The Iowan

The 'Pigs Is Pigs' Phenomenon

By Fred W. Lorch

Today if you ask an Iowan under forty years of age if he has ever heard of Ellis Parker Butler, or his book, Pigs Is Pigs, the probability is that few would claim knowledge of either the man or his book. Yet for more than a quarter of a century, from 1906, when Pigs Is Pigs first appeared in book form, until well into the 1920's, Ellis Parker Butler was not only one of Iowa's most prolific writers but a humorist of national reputation, rivaling such personalities as George Ade and Eugene Field.

Born in Muscatine in 1869, he dropped out of high school at the beginning of his second year in order to contribute to the support of the family. During the next eleven years he worked as a clerk and salesman in various local business houses -- a spice mill, an oat mill, a crockery store, and finally, for a period of nearly eight years, for a wholesale grocery company where his father was bookkeeper and secretary.

By his own confession he was fired from the oat mill for mailing a contents list and a bill of lading for a car of oatmeal to one "Henry Smith, of New York."

While the freight agent in New York City tried to find the proper Henry Smith, the car stood idle for days in the freight yard; and by the time delivery could be made, bole weevils had gotten into the oatmeal. Butler also acknowledged that he might have been fired from the wholesale grocery had his father not been secretary. As for his job at the crockery store, he claims he "broke more in a month than two months wages" amounted to.

While the freight agent in New York City tried to find the proper Henry Smith, the car stood idle for days in the freight yard; and by the time delivery could be made, bole weevils had gotten into the oatmeal. Butler also acknowledged that he might have been fired from the wholesale grocery had his father not been secretary. As for his job at the crockery store, he claims he "broke more in a month than two months wages" amounted to.

It is quite apparent that Butler's job difficulties arose from sheer inattention, for his heart was certainly not in clerking, or selling spices, oatmeal, crockery, and groceries. What he really wanted to do was to write humorous poetry and stories and get them into print. During working hours when he should have been concentrating on his job, he was composing poems in his head, or planning the development of some humorous story or sketch. As far as Butler was concerned, his real work began about nine o'clock in the evening, when, after a brief visit with family or friends, he went to his room and wrote till midnight or after. Many of these early pieces appeared in the local newspapers, especially in the Muscatine News, some of them under the pen name "Elpabu Samantha Smith." "Elpabu" was, of course, derived from the two initial letters of his full name. Mainly, however, he aimed at such national humorous magazines as Truth, Judge, and Puck, and was highly gratified when these magazines accepted his contributions and sent him a check in payment.

Encouraged by this success, and finally convinced that he was "wasting his wit on the desert air," as he said, he concluded that instead of selling navy beans in Muscatine he might better be in New York selling his manuscripts. When a good friend offered to pay his fare there for the sake of company, he gladly accepted and went to interview the big city editors. One of these was Tom Masson, for twenty-eight years literary and managing editor of Life. Masson listened sympathetically and recommended that the aspiring young humorist make a try at literary freelancing in New York. With industry and good luck Butler might very well, he believed, make enough of a living with his pen to risk the move. It was all the encouragement Butler needed. He returned at once to Muscatine, managed to borrow two hundred dollars to tide him over in New York till he could get a start, and then hastened back to the big city.

He rented a hall bedroom and started to work. But a curious thing happened. He discovered that he simply could not settle down to write in the daytime. "My muse," he reported, "went back on me." The fact was that he had become so accustomed to writing at night while working at other occupations during the daytime that a radical shift in the pattern proved insurmountable. At night, alone in his room in the strange city, he was too homesick to write.

After several weeks, running low on money, Butler looked for a job and luckily found what purported to be an editorial position with a tailors' publication. He found that the editorial work consisted mostly, he recalled, in taking a big roll of fashion plates and peddling them to little tailors about town, and soliciting advertisements from the importers and jobbers. "In this work I traveled all over the East and Middle West," he said, "and as soon as I got to work my muse came back. I wrote the first 'Mr. Perkins of Portland' story while in Cleveland."

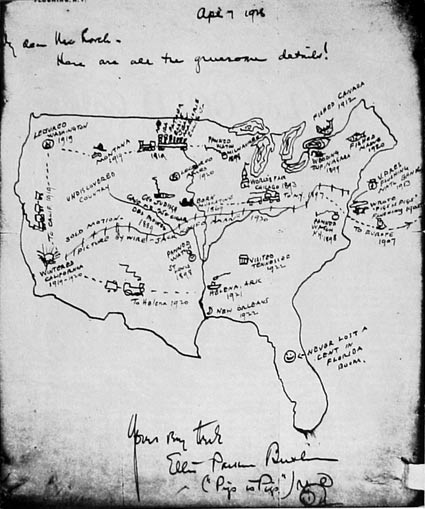

That first year on the road was a particularly difficult one. Often he found himself so short of money that he was forced to pawn his watch in order to keep going. (An examination of Butler's autobiographical map, printed herein reveals that in 1898 he pawned it at least three times in as many different cities -- New York, Milwaukee and St. Louis.)

By June of the following year, however, he had prospered enough to make a hasty trip back to Muscatine to marry his waiting sweetheart, Ida Anna Zipser. The wedding took place June 29, 1899, and as the autobiographical map shows, the young couple spent at least part of their honeymoon, in accordance with the popular fashion of the time, at Niagara Falls.

Click for larger image

Shortly after his return to New York he was offered, and he accepted, the assistant editorship of a wallpaper publication. Thereafter, for a time, he worked for an upholstering journal. All these editorial and newswriting assignments for trade journals led him, about the turn of the century, to start a trade journal of his own, the Decorative Furnisher.

Whether or not this journal proved financially profitable is not known, but soon after moving to Flushing, New York, which became his permanent home, Butler sold it. He began, now, seriously to devote himself again to literary production, and it was not long thereafter, in 1905, that Pigs Is Pigs, upon which his literary fame was chiefly to rest, first appeared in the pages of the American Magazine. The story, one of a series on the experiences of a railroad station agent by the name of Mike Flannery, was an instant success -- so much of a success, indeed, that it set the entire nation laughing at Flannery's predicament concerning a shipment of guinea pigs, and thrust a greatly surprised and jubilant Butler into the national spotlight.

Butler's popularity did not go unnoticed by Iowans. They discovered that he was a native of Muscatine and had done a good deal of early writing there. When this fact came to the attention of Edgar R. Harlan, Curator of the Iowa Historical Department, he decided to acquire a copy of Butler's book for the Iowa Authors Collection in the Historical Library. The story of this episode has frequently been told but is amusing enough to bear retelling.

Harlan, it should be pointed out, was an exceedingly able and devoted collector of Iowana, a great curator. He once described himself to this writer as a "pack rat" who busied himself, among many other duties, in assembling all the items relating to Iowa history he could lay his hands on. It is understandable, therefore, when Ellis Parker Butler's prominence became a matter of state pride, that Harlan sought to establish a connection with the popular humorist and get from him an autographed copy of Pigs Is Pigs.

In a letter to Butler, Harlan asked for an inscribed complimentary copy. He explained that he had at his disposal neither the funds nor the authority to purchase it for the Department. He also sent Butler an application for membership in the Iowa Historical Department, together with a formidably extensive questionnaire concerning his personal history. The form was apparently designed to supply detailed information for future historical reference.

Butler's reply was characteristically humorous.

Dear Sir:

I am very glad indeed to aid you by filling in the application blank. You can have your doctor call to make the examination any day after 4 o'clock.

I have sent a lot of books to some gentleman in Iowa City, who said he was some sort of historical Society or other. He must have been an official Iowan, too, for he couldn't pay for the books either. Wouldn't it be a good idea to work up a pull with the legislature and do away with "Having neither funds nor authority"? Maybe if you spoke to Paddy Welch he might work a pull for you.

I'm sending you a copy of Pigs is Pigs which I present freely to the great state of Iowa which can't afford to spend 25cts for it.

Yours sincerely,

Ellis Parker Butler

The "gentleman in Iowa City" Butler referred to was Benjamin Shambaugh, for many years Superintendent of the Iowa Historical Society and a colorful figure in Iowa City. He, too, was an avid collector of Iowana, especially in the fields of history, politics, and literature. In the fly-leaf of The Water Goats, one of the books he sent to Dr. Shambaugh, he inscribed the following humorous bit of verse:

"O Happy, Happy Iowa!

How joyous thou shouldst be

Upon thy eastern side close clasped

By fair Miss Issippee

While on thy west that dusky maid,

Miss Ouri, clings to thee!

Ah, I, also, were happy with

Two misses, hugging me!"

The questionnaire concerning his personal history which Harlan sent along with the application plainly dismayed Butler. He began answering the questions seriously enough, but as he progressed his mood changed to humor and finally to rebellious hilarity.

To the question "Emigrated to America, when?" he replied "From Heaven, 1869." "Place of death?" -- "Sorry, but I can't give this." Occupation of Father?" -- "Father." "Political offices?" -- "None, always earned my own living." "Politics?" -- "Anything to beat Bryan." "Religious denomination if any?" -- "Golf." "To whom married second time?" -- "Not decided yet." Date of his or her death?" -- "Mince Pie." "Place of his or her death?" -- $7.61." "Parents' residence at time of marriage?" -- "4%." As Harlan read through it, he had no doubt that he was dealing with a free-spirited humorist.

The copy of Pigs Is Pigs that presently came to the Curator's desk was inscribed by the author, as he had requested, but hardly in a fashion he had anticipated. On the fly leaf was penned the following verse:

To Iowa

Dear Iowa

State of my birth

Accept this book --

A quarter's worth

Oh State of corn

Take it from me

And ever let

Thy motto be --

"Three millions yearly for manure

But not one cent For literature."

Ellis Parker Butler

Nothing made Harlan prouder in later years than to get out the inscribed copy of Pigs Is Pigs and point to Butler's poem.

The success of Pigs Is Pigs was truly phenomenal for so brief a work, for it comprised only 37 pages in a small-sized book. When Golden Book magazine re-printed it in 1926, the editor claimed that a million copies had been sold. At five cents a copy royalty this meant $50,000 for Butler. No doubt additional copies were sold after 1926. As late as 1945 it was reprinted in The Best American Short Stories, in the Modern Library edition published by Random House.

An ironic disclosure about the title Pigs Is Pigs came shortly after Butler's death. According to Edward Weeks, a well-known editor, Butler never created the title. Weeks reports that during three revisions of the manuscript prior to publication, the title was "The Dago Pig Episode," but when it was published it was changed to Pigs Is Pigs and the editor (Ellery Sedgewick of American Magazine) had done the christening.

Butler never again succeeded so handsomely with any of his later writings, but the wide sale of Pigs Is Pigs and its great popularity spurred him on to greatly increased literary production. A sketchy survey of Readers Guide reveals that between 1905-1909 he published forty items, comprising poems, short stories, and humorous essays on a variety of topics. During other five-year periods he was equally productive. It should be observed also that over the years his writings appeared in at least twenty-five different magazines of national circulation, including all leading ones.

Outside of Pigs Is Pigs and possibly Goat Feathers, very little of Butler's work is remembered today. His humor played along the surface of life. Rarely did he touch it deeply. If ever he arrived at the perception that humor, to be great, is rooted in the pain and tragedy of human existence, that fact is rarely, if at all, revealed in his writings. Perhaps he aimed only at the comic, or, as he complains in Goat Feathers, perhaps he was too often diverted from the business of writing by a multitude of demands upon him for public service to analyze the nature of his art. What appeared to give him satisfaction, and the public pleasure, was the light, humorous treatment of simple themes -- boys and their experiences, the complications and amusing frustrations of domestic life, the autobiographical stories and essays,

Critics have occasionally pointed out that such boys stories as "Swatty" and the Jibby Jones books, which have the Mississippi river as a background, invite comparison with the river stories of Mark Twain. Unfortunately they do not profit by such comparison.

Like many other successful author Butler had advice for young writers, which if not profound, at least came straight out of his own experience. "My advice," he said, "is to get an outside job if possible, something that keeps you in the open air. It gives you exercise, brings you into contact with people and situations, and keeps you so far from a desk that when night comes you want to get at it, not away from it, as is usually the case when you have worked all day in an office, and have only the evenings to give to writing. A taxi-cab driver's position is about the best sort of a job, I think."

More immediately fruitful, to Iowa, at least, was Butler's advice to Mr. Harlan to pressure the legislature for funds for the purchase of books for the Historical Library. Not long thereafter such funds were provided, and there can be little doubt that Butler's bitingly satiric lines "Three millions yearly for manure but not one cent for literature" turned the scales in his favor.