from Red Cross Magazine

Brad & Dunk, Junkmen

by Ellis Parker Butler

I -- I -- I yish we eated yimburger cheese at our house," said Billy Brad one day at dinner.

"Horrors! Limburger cheese!" exclaimed Mrs. Bradley. "What ever makes you think of such awful things, Billy Brad?"

"Why, it -- it's got tim-foil onto it," said Billy Brad eagerly.

"There!" cried William Bradley, Senior. "There! Now I know why you have been watching me, Billy Brad! You're one of the foil-hounds. And you," he said to Mrs. Bradley, "thought it was measles!"

"And you," said Mrs. Bradley, "thought it was father-worship, 'a phase,'" she quoted, "'through which all boys pass when five years old, my dear.'"

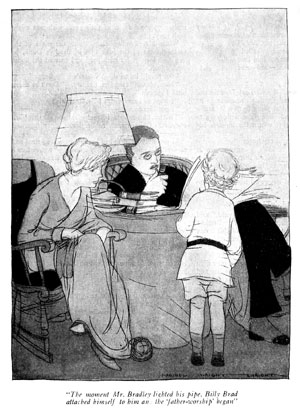

For several days Billy Brad -- which is to say William Bradley, Junior -- had been haunting his father. The moment Mr. Bradley reached home and lighted his pipe, Billy Brad attached himself to his father and began the haunting business. His big blue eyes watched Mr. Bradley fill his pipe, watched his lips as he puffed the blue smoke into the air, and sighed a sigh of happiness whenever Mr. Bradley emptied the ash from the pipe and filled it again.

"I can't imagine what makes Billy Brad act so," his mother had said. " I do hope he is not going to be sick. Of course I know how he admires you, William, but he has never been content to be still so long without talking. He does not seem to be able to take his eyes from your face."

"Perhaps the dear little kid is afraid I am going to war," Mr. Bradley had answered with some emotion. "Five-year-olds have strange ideas. He does not realize that I am too old to be called. To him I am still young and brave and a man of might. It is touching, to me, to see him. It is father-worship -- a phase through which all boys pass when five years old, my dear."

"I only hope it isn't measles coming on," Mrs. Bradley had said.

It was neither measles nor father-worship; it was, as Mr. Bradley phrased it, the "foil-hound" waiting for his prey, which was the tin-foil lining Mr. Bradley's package of tobacco.

For some weeks after that it was tin-foil only -- "tim-foil for the Yed Twoss" -- and Billy Brad hoarded it and gloated over it, carrying it to the kindergarten every Friday morning. He developed the "tim-foil eye," a product of the war.

He could see, on the sidewalk or hidden in the deep grass, specks of tin-foil so minutely insignificant that Mrs. Bradley could not have seen them with her reading glasses. He would stop and examine a grain of sand that sent up an illusive sparkle. He rescued, gloatingly, from the sandy clay of gutters, strange, damp wads of decaying paper and gloried as he separated, from between the paper and its half-inch caking of mud, fragile bits of tin-foil.

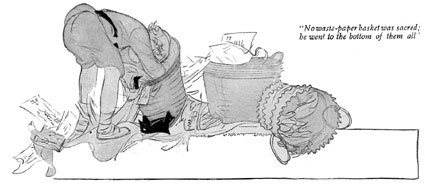

He haunted the kitchen, standing on chairs to investigate the inner linings of cracker cartons and tea packages and food parcels, seeking tin-foil. No waste-paper basket was sacred; he went to the bottom of them all a dozen times a day. Mrs. Bradley even caught him gazing longingly at the Carter's full garbage pail, as if its depths might be concealing tin-foil. He asked his mother if the silver backs of Mr. Bradley's hairbrushes were tin-foil. He had designs on them.

One day, when school had closed, Billy Brad came running into the house.

"Mamma," he cried excitedly, "I want all the old yags, and all the old bottles, for because me and Dunk --"

"Now, Billy Brad," said Mrs. Bradley, "I will not have you rushing into the house like this, slamming the screen door. And you must not say 'Dunk.' Mrs. Carter does not like to have him called 'Dunk.' His name is Duncan. You must call him Duncan."

"Yes'm. Duncan. And -- and -- and me and Dunk --"

"Duncan and I."

"Yes'm. Duncan and I. I yallers say Duncan and I. And -- and -- and me and Dunk we're going to be the yunkmen. And -- and I'm going to own it, and -- Dunk's going to own it, and -- and we're both going to own it, but -- but I'm going to own it the mostest because I got my wagon, and --"

"Not 'mostest.' You must say 'most.'"

"Yes'm. 'Most.' And Dunk's going to own it mostest, too, for because he's olderer than me. And -- and we is both going to own it the mostest, and -- and we want some old yags --"

"Rags, not 'yags.' And anyway I have no time to get old rags for you now. You can play junkmen if you wish --"

"In our yard?" asked Billy Brad.

"I much prefer to have you play in our yard," said Mrs. Bradley. "But remember this, Billy Brad, I don't want you to take a single rag out of this house without asking my permission. Now go out and play with Duncan." She was glad Duncan Carter was willing to play with Billy Brad, for Duncan was a clean, bright boy and older than Billy Brad. He was eight years old and sedately correct in his mode of speech, and Mrs. Bradley was beginning to be worried by Billy Brad's whole-souled abuse of the English language. He no longer said "ump-a-ump" for "elephant," having improved it to "yellumpump," which was quite a notable stride; but this and the ability to say "yi-yoss-er-yoss" for "rhinoceros," instead of "noss-er-noss," had marked a distracting and increasing fondness for the letter "y". He was now able to begin almost any word, from "apple" to "zebra" with a "y", and seemed to glory in "yapple," "yebra," and similar errors of speech. Mrs. Bradley hoped that association with Duncan Carter would correct such things as Billy Brad's perfect impartiality in calling both a lemon and a gentleman by the common name of "yemmon."

Mrs. Bradley was also glad that Billy Brad and Duncan were willing to play in the Bradley yard, for Billy Brad had reached the wanderlust age and was only too eager to be far and away whenever possible. He often came home from his jaunts abroad far from clean, and the Bradley yard was such a neat, clean place for the boys to play. Mr. Bradley saw to that. His greatest pleasure, on these long daylight-saving days, was to clip the neck of the last unruly blade of grass that raised its head above its fellows, or to capture and destroy the lone fallen leaf that marred the immaculate neatness of the yard, front or back. He boasted that there was but one other such yard in Westcote. That was Mr. Carter's yard. It, too, was speckless. Mr. Carter and Mr. Bradley were friendly but keen rivals in this matter. People spoke of their yards with awe mixed with envy.

When Mr. Bradley came home the night of the establishment of the junk firm of Brad & Dunk, he gave one look at his backyard and entered the house with a rush.

"See here!" he cried. "Where's Billy Brad?"

"Now, please!" said Mrs. Bradley. "Don't be angry until I explain."

"I want to know where Billy Brad is!"

"I put him to bed --"

"Without his supper, I hope! Did you see that yard of mine? Old tin cans, rubber boots, dirty rags, old iron --"

"I put Billy Brad to bed because he was so tired and so -- soiled," said Mrs. Bradley calmly. "I gave him a good bath and put him to bed and he was asleep in a minute."

"And what are all those old sardine cans and tomato cans doing out there? You know I want that yard kept neat."

"Now, William, just one minute. I told Billy Brad he might do that."

"You told --!"

Mr. Bradley dropped into a chair. He could not believe his ears.

"It is just a game he is playing with Duncan Carter," said Mrs. Bradley. "He asked me if they could play junkman in our yard and I said they might. I had no idea they would gather the old tin cans from the vacant lot --"

"They did that, did they?" said Mr. Bradley, grinning. He could picture Billy Brad -- the cunning little tyke -- hunting through the tall grass, pouncing on old tin cans with cries of joy.

"I was at the Red Cross all afternoon," Mrs. Bradley said, "and did not get home until a few minutes ago."

"Well, 'man is born to trouble as the sparks fly upward'," quoted Mr. Bradley, "when he has a five-year old boy."

"A man doesn't have a five-year old boy when he is born," said Mrs. Bradley pleasantly, for the storm might have been much worse. She had feared it would be.

No more was said about it until after dinner, when the dishes had been washed and Mrs. Bradley sat at one side of the living room table with her knitting and Mr. Bradley at the other side with the Westcote Eagle.

"They did enjoy it so, William," said Mrs. Bradley, looking up.

"Who enjoyed what?" asked Mr. Bradley, his eyes still on his newspaper.

"Billy Brad and Duncan. Playing junkman," said Mrs. Bradley. "It is so sweet the way those boys have their temporary enthusiasms. Today this junkman game was the only thing of importance in their world, and tomorrow they will be just as wild over something else."

"And I will have to clean up the yard. These sweet but temporary enthusiasms --"

The telephone bell interrupted him.

"I'll go," said Mrs. Bradley.

"Never mind. I'll go up. It's probably Carter, wanting to guy me about the look of my yard."

In a few minutes Mr. Bradley came down again.

"That was funny," he said. "Some smarty neighbor that saw my yard, I suppose. Tried to tease me. Asked me if I was the junkman. I hung up on him. If a man thinks it is a joke to make a tired man climb a flight of stairs --"

The telephone bell at the head of the stairs rang again. Mr. Bradley jumped from his chair and hurried to the telephone. He was gone longer this time, and Mrs. Bradley heard the sound of his voice. He came down holding a piece of paper in his hand, and picked up the evening Eagle.

"Somebody I never heard of, named Caggerty, 268 Willow Street," said Mr. Bradley, with annoyance, "He insisted he had the number right. He told me to look on the third page of the Ea -- Hello: Well, by George!"

"What is it?" asked Mrs. Bradley.

"What is it? It's those boys," said Mr. Bradley. "They are some boys. Didn't you see this in the Eagle? They're advertising."

"Advertising! What for?" asked Mrs. Bradley.

"What for? For more junk to decorate my yard with, that's what for. Listen to this: 'Brad & Dunk, Junkmen. Junk will win the war. All kinds of old junk wanted free. We get it and give it to the Red Cross. Rags or old newspapers or iron or bottles or old tin cans or anything like that. Telephone to Mr. William Bradley's house or Mr. James Carter's house and we will come and get it. We need lots of it!'"

Mr. Bradley looked at his wife.

"Oh," she said, rather weakly. "That was why they had to go downtown this afternoon."

"I suppose," said Mr. Bradley with emotion, "they will sell only in carload lots. That's the way junk is usually sold, isn't it? They won't sell until they have a carload of old tin cans in my back yard, and a carload of old newspapers, and a carload of old rubber shoes. They didn't say anything about moving the house over against the fence and building a railway spur into the backyard, did they?"

Mrs. Bradley did not answer this gently sarcastic query. The telephone bell interrupted her. Half an hour later she called down the stairs to Mr. Bradley: "Bring my knitting up when you come, William, don't think I'll come down again while the telephone bell keeps ringing -- Yes, hello! Yes, this is Brad & Dunk. It's their mother speaking. Yes, I hear -- Walker, 628 Overton Place. I'll tell them. Thank you."

Late that night, when Mrs. Bradley had returned to bed after answering a very late telephone call, Mr. Bradley spoke.

"I don't believe it will be as bad tomorrow night," he said hopefully. "Nearly everyone in Westcote must have telephoned tonight."

"And some must have telephoned to Carter's," said Mrs. Bradley.

"But on the other hand," said Mr. Bradley, "they will all probably telephone every time they have any canned thing for dinner. And every time their old rubbers are ready to discard. And every time they have another old newspaper. Forever and ever! Years from now people we never met will be telephoning us to come and get their worn-out coffee pots. When we are old and gray people will call us up at midnight and ask us to send for their old bed springs."

The next morning, before hurrying for the train, Mr. Bradley went out with his son to view the junkyard. Duncan Carter was already on the spot. With the crisp, polite manner of a successful businessman he discussed with Mr. Bradley the future of the firm of Brad & Dunk, Junkmen.

"I pessoom, the way telephones are coming in," said Duncan, "we will have considerably more junk than we expected to have, Mr. Bradley. It looks like it."

"And -- and I'm going to be the horse, ain't I, Dunk?" said Billy Brad eagerly.

"I thought you were a partner," said his father.

"Yes. I'm a parpner. And I'm a horse. And -- and I'm one of the yunkmen. But Dunk, he ain't a horse."

"Well, it is for a good cause," said Mr. Bradley, "and I'll let you use the backyard until peace is declared and for six months thereafter, as the war legislation puts it. You see that rose bush and that clothes-post? You may use the space back of a line drawn between them. An imaginary line, of course."

"And -- and -- and I'll drawer the yimagery yine," cried Billy Brad, "for because I've got a yed-pencil --"

"An imaginary line, son," said Mr. Bradley, "does not have to be drawn. It is a line that is not there."

"Yen -- yen where is it, papa?"

"It is not anywhere. You just think it is there."

"Here?" asked Billy Brad, placing himself midway between the rose bush and the clothes-post.

"Yes, there."

"But -- but I don't not shink it's here," said Billy Brad, and he took three long strides forward. "I shink it is here. For -- for because I can't not shink a yimagery yine is anywhere yelse."

"Very well," said Mr. Bradley. "I'll not quibble. Either place will do. But you must not pile junk in front of the imaginary line. Is that understood?"

"Yes, sir," said Dunk promptly, but Billy Brad hesitated.

"But -- but --" he questioned; "but, papa, what if a great, big wind come and blowed the yimagery yine all -- to -- pieces!"

"If that happens," said Mr. Bradley, "or if you see a great, big wind coming up, you'll have to take a couple of great big pieces of imaginary iron and put on the imaginary line to hold it down."

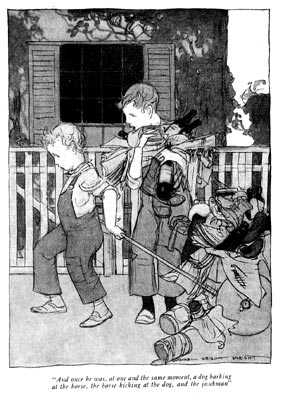

The firm of Brad & Dunk, Junkmen, did a prosperous business. As a horse Billy Brad was an untiring draft animal, and it was remarkable how he could, upon arriving at one of the telephoned addresses, imagine himself standing hitched to the wagon, with his nose in an imaginary nose bag, switching imaginary flies from his flanks with an imaginary tail, while, at the same time, he was the junkman and threw tin cans into the wagon. Many people seeing Billy Brad's jaws working, thought it was Billy Brad, the junkman, chewing gum, when it was Billy Brad, the horse, munching oats. And once he was, at one and the same moment a dog barking at the horse, and the horse kicking at the dog, and the junkman driving the dog away from the horse. They were happy days for, all the while, he was also Billy Brad, gathering junk to sell for the Red Cross.

Duncan Carter managed the firm's finances and transacted the vital business affairs of the firm, arranging with Rizzo, the real junkman, for the sale of the gathered junk. This was probably preferable, since Billy Brad was still unconvinced that a nickel was not more to be desired than a dime, being bigger. The money the two lads secured for the Red Cross was considerable and their spirit and the novelty of their doings helped greatly in more ways than one.

There came a time, however, when Duncan Carter fell a victim to the dread ravages of measles and was forced to accept temporary internment in his bedroom. A willing substitute offered himself in Ted Hinman, but a substitute far less particular in some matters than Duncan was. He was less particular, for one thing, regarding the vested property rights of fathers and yards of which they are inordinately fond.

Mr. Bradley came home one evening to find the tin cans and old newspapers straying far beyond their legal limits. This was exasperating. It was too much!

"Where is Billy Brad?" he asked the moment he entered the house.

"In bed," said Mrs. Bradley. "I'm sure he is not asleep yet; I just tucked him in."

Mr. Bradley went up the stairs two steps at a time.

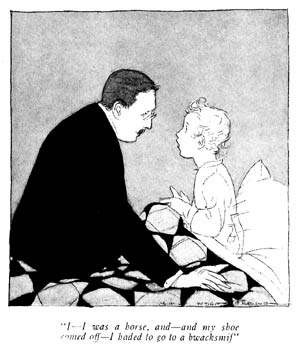

"Hello, papa," said Billy Brad, popping straight up in bed. "I -- I was a horse, and -- and my shoe corned off, and -- and I haded to go to a bwacksmif --"

"Now, wait!" said Mr. Bradley. "You can tell me about that later. There are tin cans almost out to the front gate. Didn't I show you a line --"

"Yes. It was a yimagery yine," said Billy Brad eagerly. "And -- and I couldn't not find yany yimagery yiron to put down onto it, and a great, big storm comed up, and the wind blowed the old yimagery vine clear across the street, and -- and I hunted for it, and I couldn't not find -- I"

"Now, hold up, Billy Brad," said his father. "You know that is not the truth. There was no wind. It happens that I had my office windows open all day and I would have felt a wind if there was one. There was no storm, and there was no wind. Wouldn't I have known if there was, Billy Brad?"

Billy Brad looked up into his father's face with his honest, big blue eyes.

"No, papa," he said. "For -- for because it was a yimagery wind, and -- and nobody can't not feel a yimagery wind."

He paused a moment.

"But," he added cheerfully, "a yimagery yine can."

"Why can it?" asked Mr. Bradley.

"For -- for because we needed more room for yunk," said Billy Brad frankly.