from Red Cross Magazine

The First Day of School

by Ellis Parker Butler

Because two new factories had opened in the town there were a great many new children to enter the school and Miss Potter, the principal, stood just inside the door to ask questions and send the children to what might be the "rooms" for which they were fitted.

"What reader did you use last term?"

"Second reader."

"That room," said Miss Potter, pointing, and then to the next:

"What reader did you use last term?"

"Third reader."

"Upstairs, the first door."

Some of the children did not know what reader they had had.

"I didn't have a reader; I had a gog-o-phy," said a little girl.

"What do you know about Italy?"

"It's shaped like a boot and runs through North and South America and empties into the Caspian Ocean," stammered the little girl.

"First reader; that room," said Miss

Potter promptly, "and you, young man?"

He was an unusually attractive boy. To Miss Potter, at least, he seemed unusually attractive, but that may have been partly because he was a little boy she had not seen before. During a school year she came to know the little boys quite intimately and some of them were not quite as attractive at the end of the year as at the beginning. But this boy really was attractive. There was something appealing in his diffident, hesitating manner. His hair was marvelously parted and "slicked." His face shone with the super-cleanliness that is seldom seen on a boy's face except when he is going to a party. His legs were in spotlessly white cotton stockings, his stubby shoes glistened with blackness, and at the front of his snowy sailor collar a huge and perfectly tied bow of new plaid silk ribbon made a stunning butterfly.

"What a sweet boy!" thought Miss Potter.

There was a pause in the flood of youth that had been pouring into the building. As a matter of fact, the "sweet" boy had waited for that very pause, because he was much frightened. It was his first day in any school. He had waited until he could steal in alone.

His ideas of "school" were vague and strange and he felt conspicuous and as if he might make some silly mistake at which the other boys and -- oh, horror! -- the girls would laugh. He had looked in at the door several times and had always seen Miss Potter standing there by the newel post, questioning one after another. He had hoped she might go away and that he might slip into the schoolhouse and into a seat and not be seen. But evidently she did not mean to go away until the last child had entered, and now he was there, standing before her. He felt hot and uncomfortable. His face was red.

Scotty, he of the hard fists, had told him about certain boys who were "teacher's pets." As the new boy understood it, "teacher's pets" were the lowest of the low. They were boys so mistreated by nature and born under such an evil star that teachers liked them. This was, of course, the utmost limit of degradation: It made one an outcast from the best, spit-ball-throwing, girl-teasing male society. And one of the proofs that a boy was a teacher's pet was that teacher, instead of assuming a "glad you're getting along home" air, stopped one and talked to him in an intimate, affectionate manner. And now Miss Potter was stopping him!

"You're a new boy?" said Miss Potter pleasantly.

"Yes'm," he said miserably.

Miss Potter was not a slender sylph of a girl. She was a large, motherly woman with a large, motherly face that could be surprisingly stern or exceedingly pleasant. Now her face was pleasant. It was more than pleasant; it was friendly.

"She's making me into a teacher's pet -- teacher's pet -- teacher's pet!" ran distressingly through the boy's mind, and he longed to scratch or kick or run howling away, but the truth was that he was at heart and by nature the only kind of boy that is a teacher's pet. He was a bright boy, and a clean boy and as good as a boy ought to be, with only a streak of mischief here and there, and not malicious mischief. So he could not scratch or kick or run howling away. He stood and blushed until his checks were like polished rose-leaves.

"I was sure that I had not seen you before," said Miss Potter pleasantly. "What is your name?"

"Bert," he said unwillingly.

"I'm sure that is not all of it," she said. "It isn't just Bert, is it? Bert isn't all of any boy's name. Is it Albert?"

He looked down and did not answer. She was asking him to utter the syllables that were the greatest load of shame he had yet been called upon to bear.

"Is it Albert?" she insisted, smiling.

"No mam."

"You musn't be shy. A schoolboy musn't be shy. What is your name?"

"Ethelbert," he murmured so weakly she could hardly hear him.

Miss Potter was a very wise woman and a very tactful woman, which was why she had risen to be principal of the school. She was one of those rare persons who do not have to study human nature -- who know it intuitively. She guessed at once that the name was a great trial to the boy, that he had already known the agony of being called Ethel by scoffing boys who chanted in chorus, "Ethel is a girl's name! Ethel is a girl's name!

"That is a king's name," she said cheerfully. "You ought to be very proud to have the name of one of the brave Saxon kings, Bert."

She was such a wise woman that she did not make the mistake of saying 'Ethelbert." She said "Bert."

"Yes'm," Bert said.

"But that is not all your name. What is your full name, Bert?"

"Bert Carter."

"Why, of course!" Miss Potter exclaimed.

She remembered him now. He was the small nephew Miss Anne Carter had taken to raise, the boy she had seen often enough in the big Carter front yard, with long, golden curls. She had felt sorry for him even then, he was such a big boy to have curls, and she knew so well how other shaved-headed boys must tease him. And with a name like Ethelbert, that could be shortened to Ethel!

"Do you ever fight. Bert?" she asked, and she knew what the answer would be.

"When they call me Ethel I do." he said

"Well --"

It was on the tip of her tongue to say that if anyone called him Ethel he must come and tell her, but she thought better of it.

"What, reader did you have last, Bert?" she asked.

"I didn't read out of a reader last," he said. "I read out of 'Tales of a Grandfather.' And out of Shakespeare. But mostly out of 'Tales of a Grandfather.'"

"Oh! Haven't you read out of a reader?"

"Yes'm."

"What one?"

"Fourth reader."

"The room at the head of the hall, upstairs, Bert," she said, and watched him as he went up, walking carefully on the glistening, recently varnished treads.

As he climbed the stairs he was glad. For the first time since he opened his eyes in bed that morning he was glad. As each step carried him higher above the first floor of the school a greater feeling of relief possessed him. The world was good, after all. His Aunt Anne had let his curls be cut, Ethelbert was the name of a brave Saxon king, the lady at the foot of the stairs had not cried out in holy horror when he said he fought those who called him Ethel and, best of all, each step upward was carrying him farther from Miss Goosick's room!

The most dangerous boy is a weeping boy. All boys are ashamed to be seen weeping. When a boy is cruelly struck he will fight, but when he is made to weep and fights, he fights in a rage that is sometimes awful to see. Never imagine that a boy that is blubbering is a tamed, cowed creature. He is a mad and angry creature. He will fight like a demon then, to avenge the shame he feels his tears to be. More than anything else in the world a boy hates to cry, at least when there is a witness.

A boy, feeling oppressed and downtrodden, may find a variety of damp, sad comfort now and then in going out behind the woodshed and weeping over his woes in solitude, but he feels that it is disgraceful to let anyone see him cry. Men do not cry; it is women's work. Pirates or soldiers or cowboys or detectives or Indians never cry; so boys never cry. Even our soldier boys in France during the war, wounded, suffering, homesick, heart-sore, hated to cry or be seen crying, and the best tales our Red Cross nurses have brought home are of the cheerfulness of the Americans even when they lay suffering in their weary hospital beds, maimed or mangled or sick.

That was why Bert Carter's heart grew lighter as he climbed the stairs and left Miss Goosick's room behind him. Miss Goosick made boys cry.

Ethelbert had never attended school because his Aunt Anne had taught him at home. Even stupid boys learn faster under a private tutor, and Miss Anne was the most loving and eager of tutors, while Ethelbert was by no means stupid. He was a bright boy. He had, indeed, progressed so far that Aunt Anne no longer felt capable of directing him. He knew as much arithmetic as she knew, and the time had come when he needed teachers able to take him further than she could. Now she must give him up.

All he knew about school itself he had learned from Scotty, and Scotty had left no doubt regarding Miss Goosick.

"That's her room," he had told Bert when they passed the school. "That's Goosick's room. Gee! I'll bet you'll be in her room, too. I'm glad I'm going to the other school before I have to be in her room. I wouldn't go to her room, that's all!"

"Why? Does she lick you?"

"Lick? Think I'd care for any licking a woman teacher could give me? If Goosick licked me I wouldn't care. I wouldn't care if she licked me with a strap with a buckle on the end of it. That ain't anything -- a licking ain't."

"What does she do?" asked Bert tremulously.

"Kisses you," said Scotty. "She makes you cry and then she kisses you. You bet if I was in her room and she tried to make me cry I'd show her!"

"Does she try to make you cry?"

"Yes, and she does it, too. She can make anybody cry. Well -- you know big Cuffy Mallon, don't you? She made him cry. She made him blubber like a baby. Ed Snooks saw him. And then she made Ed cry, too. Cuffy said so. He saw him. Why, sometimes she keeps in a whole row and makes them all cry. One right after another. Ed Snooks says she keeps somebody in every day and makes 'em cry."

"Does she -- how does she?" asked Bert, wide-eyed.

"She hugs them." Scotty said. "It don't make any difference whether it's a girl or a boy, she hugs them and makes them cry. And sometimes she cries herself. Yes, sir! Ed Snooks says that sometimes there'll be a whole row and her, too, all crying at the same time."

"But if they don't want to cry --"

"Well, they can't help it, can they? Ed Snooks ought to know. He wouldn't cry if he didn't have to, would he?"

Bert thought of Ed Snooks and had to admit that Ed Snooks would not cry unless he had to. Ed Snooks had red hair and a pug nose and it was impossible to picture him shedding tears.

"When she keeps them in after school for something," Scotty said, "she takes them one at a time and sits down in their seat with them and talks to them. She puts her arm across their shoulder and says how sorry she is they are a bad boy, because she had such hopes of them, and it breaks her heart to have them act whatever way it was they had acted. So then, if they don't cry right off, she cries. And then they both cry."

"I bet I won't," Bert declared.

"I bet you will. You'll be just the kind that will. You'll bawl like a calf, because you're sort of like that. If she can make Ed Snooks and Cuffy Mallon cry you'll be pie for her. And then when she's got you crying good she'll say she knows now you'll be a good boy from then on, and she'll kiss you."

"I -- I won't let her! I'll --"

"Yes, you will! You'll be blubbering away and you can't help it. That's what she does it for. She gets you all soft and girlish and then kisses you and she thinks you hate it so much you won't cut up in school again for fear she'll do it again."

"Well --"

"Well what?"

"Well, if I get into her room I won't cut up. Then she won't make me cry."

"Then all you'll be will be like Sammy Grayson. You'll be teacher's pet. She'll stand beside your desk and pat you on the head once in awhile and tell the room how good you are and how she wishes they would all be nice like you are. And all the time the fellers will be snickering at you. And the girls, too."

So Bert climbed the stairs, glad that he was leaving Miss Goosick and tears and kisses below him. At the top of the stairs he paused. There were four open doors and in each doorway stood a teacher. From the four rooms came loud noises of talking and scuffling and little screams of pretended girlish fear, and laughter and the sound of cuffing. It was the last minute and a half of untrammeled freedom. The youngsters were making the most of it.

Bert walked to the door at the end of the hall. The teacher paid no attention to him. She had just started across the hall to speak to the teacher in the opposite doorway. Bert went into the room.

"Hey!" someone shouted and a wet sponge struck him in the face. A girl -- a big girl, so big that she was wearing longish skirts and a real watch -- turned to him and wiped his face with a handkerchief that smelled of lily of the valley.

"They're awful rough" she said, referring to the boys. "They think they're smart. You'd better go down to your own room; they might hurt you, the way they're carrying on."

Ethelbert hesitated. This was his room. This was the room to which he had been sent, but these were not boys like Scotty or Ed Snooks, or even big Cuffy Mallon. These were big boys and, worse still, big girls. One of the big fellows came up to him.

"What do you want up here?" he asked roughly.

"I'm coming to school here," said Ethelbert. "I'm going to be in this room."

Some of the boys had long trousers. They looked like full-grown men to Ethelbert. The big boy who had questioned him yelled:

"Say, look who's here!" he cried. "Look who says he's going to be in our room!"

There was a camaraderie among the big boys and girls in the room. They knew each other well -- had spent years together in the lower rooms. Ethelbert felt himself an intruder. He felt that he did not belong there. The big girl who had wiped the water from his face spoke to him again and kindly.

"I guess you've made a mistake," she said. "This is the fourth reader room. What reader did you have when you came to school before?"

"I -- I never came to school before," Ethelbert faltered.

"Then you want to be downstairs, in the baby room," his informant said. "Not up here."

"Hey, look who got lost!" a big boy shouted. "He thinks this is the baby room! Go downstairs, little boy, and don't fall and hurt yourself."

They all laughed, even the kind girl, and Ethelbert turned away. There were tears in his eyes, but, of course, he could not stay in this room when none of them wanted him there. The teacher at the door did not stop him. The last bell clanged just as he passed her and she turned to her charges, paying no attention to him. She closed the door behind him and he was in the hall alone.

He stood a brief second at the head of the stairs looking down. He was vastly unhappy. The room he had just left was impossible. He would rather die than enter it again. He would have to open the door now if he went in, and the teacher would look at him with surprise. All the eyes of all the half-hundred big boys and big girls would center on him. That was something he could not, in nature, stand. No one could. The room he had just left was impossible.

But to go down was awful, too. To go down meant going into the room where Miss Goosick put her arm around one and made one weep.

Very slowly Ethelbert went down the stairs. He kept close to the wall. When he was a step or two above her Miss Potter, waiting for the belated ones who might arrive tardily, turned and looked up at him.

"But, Bert," she said, "you must not come down now. The last bell has rung."

"I don't want to be up there," he said. "I guess I oughtn't to be up there."

"Well -- " Miss Potter said, but he had slipped by her and had opened the door into the corner room before she had reached a decision. The door closed behind him.

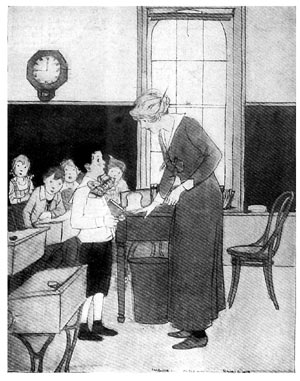

He found himself facing all the boys and girls. They were all seated, with their hands folded on their desks. Their eyes, one hundred eyes, turned toward him. He drew a deep breath, for the teacher stood at his side.

"And one more!" she said cheerfully, smiling down at him.

She was pretty. She was young, too. But Ethelbert glanced up at her fearfully. He looked at the face that smiled on him and a chill ran from his head down his spine as she raised one of her hands. He had cast his lot for the room where the teacher made you weep like a girl or put her hand on your head and made of you a teacher's pet. He could already, in imagination, feel her hand resting on his head, while the school looked on, and the hairs of his head tingled.

But she did not pat his head. The hand she raised felt in her hair for a pencil.

"Your name?" she asked.

"Bert Carter"

"Your address, Bert?"

"276 Grayson Street, Miss --"

"Did you attend this school last term?"

"No, Miss Goosick."

"Very well, Bert, you may take that seat in the second row. But I am not Miss Goosick. I am Miss Melrose. Miss Goosick has been promoted to the fourth reader room. Do you think you ought to be in her room?"

"No, mam," said Ethelbert eagerly. "I know I oughtn't to be. I ought to be in your room."

"Then take your seat," said Miss Melrose. "And now, scholars, I want you all to try to do your best this term. I want you all to do well because I don't want to have any teacher's pets."

The boy across the aisle from Ethelbert looked at Miss Melrose with deep attention and under that camouflage reached out his foot and kicked Ethelbert in the ankle. And Ethelbert, with worshipping eyes on Miss Melrose's pretty face, cautiously and happily returned the kick, for life had suddenly become worth living.