from Red Cross Magazine

Billy Brad and the Middleman

by Ellis Parker Butler

When the ears of corn in Billy Brad's cornfield began to have tassels of corn silk peeping out at the top where the ends of the husks came to a point, he knew the corn was getting ripe enough to eat, because Henry Staples said so, and Henry Staples knew all about corn. Billy Brad became quite excited! It was delightful to see so many ears of corn growing, all getting ready to be eaten.

One day, Billy Brad went through all his rows of corn and counted all the ears. Long before he was through, he lost track of the number of ears he had counted, but he knew they were a very great many, and he was sure he would be very rich when he had gathered all the ears of corn and had sold them.

"For -- for because I've got so many," he told his Uncle Peter Henry, "and -- and I only have to give twelve ears for a dozen, and -- and my mamma pays sixty cents for a dozen."

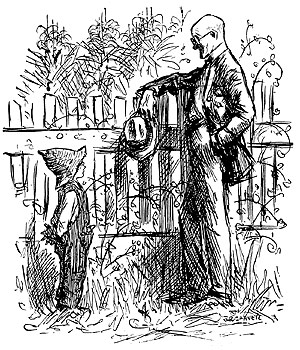

Uncle Peter Henry, who was leaning on the fence of the cornfield, looking at the tall, handsome cornstalks, turned and looked at Billy Brad's enthusiastic face and smiled, but Billy Brad did not like the smile very well.

"What are you smiling that kind of smile for, Uncle Peter Henry?" he asked uneasily. That smile worried Billy Brad, because his Uncle Peter Henry was quite bald and wore big spectacles with real tortoise-shell rims and looked as wise as an owl, and when a man as wise as Uncle Peter Henry smiles a doubtful smile, one may be sure he is thinking things.

"Was I smiling?" asked Uncle Peter Henry. "It must have been because I was thinking of the middleman."

"But who is the middleman, Uncle Peter Henry?" Billy Brad asked uneasily. "Is he somebody I have to pay rent and taxes to?"

Uncle Peter Henry laughed.

"No, Billy Brad," he said, "you don't have to pay him rent and taxes. He is the man that buys your corn."

"But -- but I'm going to sell my corn to my mamma," Billy Brad said.

"All of it? All that corn?" asked Uncle Peter Henry, waving his hand toward the cornfield. "Why, Billy Brad, you have more corn there than fifty mammas could use. It would not surprise me, if you had more corn than one hundred mammas could use. You know that."

"Do I?" asked Billy Brad doubtfully.

"Of course you do!" said Uncle Peter Henry. "So what will you do with the corn your mamma does not want?"

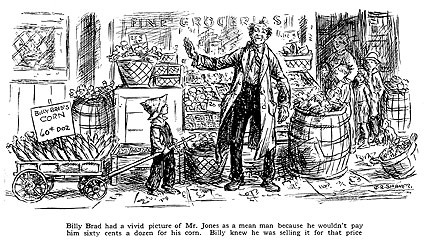

"Why -- why, I'll sell it," said Billy Brad. "I'll sell it to Mr. Jones, the grocery man, because he sells corn. He can buy my corn that my mamma don't want, and he can sell it in his grocery store."

"Of course! Certainly he can!" said Uncle Peter Henry. "He can buy all your corn and he can sell it again to people who want corn to eat. And I expect he will be glad to buy nice corn, such as your corn is, and sell it again, because that is one of the reasons he has a vegetable market in his grocery store. He has the vegetable market so he can buy corn from you and sell it to someone who wants corn. And, of course, that is why he is the middleman -- he stands in the middle. He is between you, who grew the corn, and the person who buys the corn to eat, and that is why we call him the middleman."

"Well, I don't care," said Billy Brad. "I don't care whether I sell my corn to my mamma for sixty cents a dozen or to Mr. Jones for sixty cents a dozen. I don't care who I sell my corn to, Uncle Peter Henry."

"Except," said Uncle Peter Henry, "that Mr. Jones will not pay you sixty cents a dozen."

"Won't he?" asked Billy Brad. "But I want him to, Uncle Peter Henry. Why won't he, when my mamma will? How much will he pay me for my corn, Uncle Peter Henry?"

"That I don't know," said Uncle Peter Henry gravely. "Mr. Jones will have to tell you that, but I think, perhaps, he may pay you thirty cents a dozen. Perhaps not so much as that; perhaps a little more."

Billy Brad's face fell. He looked quite sad and disappointed to hear he would only get thirty cents a dozen for his corn when he had hoped to get sixty cents a dozen for it.

"Then I think he is mean -- real mean!" he said.

"Oh, no!" said Uncle Peter

Henry. "Mr. Jones is a nice man. He is a very honest grocer, I think."

"Then why won't he pay me sixty cents a dozen when my mamma will pay me sixty cents a dozen?" Billy Brad asked.

"One reason," said Uncle Peter Henry, "is because he has to wear shoes."

"Shoes!" cried Billy Brad, quite astonished.

"And he has a wife, too," said Uncle Peter Henry, trying to hide a smile, "and she has to wear shoes. And he has children and they have to wear shoes. And they all have to wear clothes. Have you ever seen Mr. Jones' delivery automobiles, Billy Brad?"

"Yes! They're nice ones," said Billy Brad.

"But they will not run without gasoline," said Uncle Peter Henry, "and they will not run unless someone sits on the driver's seat to handle the wheel. And shoes and clothes and gasoline have to be paid for, and the wages of the delivery boy who runs the delivery automobile have to be paid every week. And that is why Mr. Jones cannot pay you sixty cents a dozen for your corn."

"Is it?" asked Billy Brad.

"Of course it is!" said Uncle Peter Henry. "Mr. Jones has only one way of earning the money to pay for his shoes and his wife's shoes and his children's shoes, and he has only the same way of earning money to pay for gasoline and to pay the wages of his clerks and delivery boys. He buys things to sell in his store and then he sells them for more than he paid for them; and the difference, between what he pays and what he sells them for, is the money he has earned to pay for shoes and everything else that he must have. You can see, can't you, Billy Brad, that if he paid sixty cents for your corn and sold it again for sixty cents he would not earn any money to buy shoes with or to do anything else with?"

"But I want sixty cents for my corn," said Billy Brad rather stubbornly. "Why don't Mr. Jones pay me sixty cents for my corn and then sell it for more than sixty cents?"

"I think he would be willing to, if he could," said Uncle Peter Henry, "but he can't. When all the other grocers and markets are selling corn for sixty cents a dozen, and when little Billy Brads are selling it for sixty cents a dozen, too, Mr. Jones cannot ask more than sixty cents. If he does ask more for his corn, people will not buy it. If Mr. Jones asks seventy cents for his corn, when all the other markets and all the Billy Brads are asking only sixty cents, no one will buy his corn. So he asks only sixty cents, and pays enough less for the corn to be able to sell it for sixty cents and have money left to buy shoes and clothes, and to pay rent and taxes, and ever so many other things."

"Oh, my!" exclaimed Billy Brad.

"Yes, indeed!" said Uncle Peter Henry. "You can hardly imagine how many things Mr. Jones has to pay for out of the difference between what he pays for corn and other things, and what he sells the corn and other things for. Out of that difference he has to pay for everything he wears and eats, and everything his family wears and eats, and for his housing and everything about his house -- gas, water, milk and everything! And out of that difference he has to pay for his store, and its lights and heat, and all his clerk-hire, and taxes and everything else about his store that costs money. And this seems to be all more or less right and proper, because the middleman is often a very useful man."

"Why is he?" asked Billy Brad, who could not quite like a man who would pay only thirty cents for his corn.

"He is a useful man, when his store is a good store and an honest store, because then it is a place where you and your mamma can go to get things she needs and must have. It would be a great deal more trouble for your mamma -- if she wanted to get her supplies for only one day -- to have to go to a soap factory for one cake of soap, and to a bluing factory for indigo, and to a starch factory for starch. Mr. Jones, as a middleman, has them all."

"And cookies, too?" said Billy Brad.

"Yes, and cookies," said Uncle Peter Henry, "and pepper. Your mother would never get her day ended if she had to go to Singapore for an ounce of pepper, and to Ceylon for a pound of tea, and to Brazil for a pound of coffee. The middleman has all these things and that is why he can be so useful, but he has to live and keep his store going, and that is why he cannot pay as much for green corn as your mamma can; it is the reason why he has to make what is called a 'profit' on everything he sells. His 'profit' is the pay he receives for being a useful middleman."

"But I wish he would pay sixty cents for my corn," Billy Brad insisted, for he had set his heart on sixty cents.

"I am afraid the only way you can get sixty cents a dozen for your corn, Billy Brad," said Uncle Peter Henry, "is to peddle it from house to house yourself. You might do that. You might take your corn around and sell it yourself. That is called 'direct from producer to consumer.' It works well, sometimes, and it leaves the middleman out of the middle, for there is no middle."

"But I've got so much corn," said Billy Brad, rather hopelessly.

"Indeed you have," said Uncle Peter Henry, "and it is that 'so much' and 'so many' that seems to make the middleman a necessity. It pays the grower better, some think, to grow great amounts of things and let the middleman sell them, rather than to grow just a little and peddle it to a few people.

Gardeners grow 'so much' corn and there are 'so many' users to sell to, scattered everywhere in different towns and in different houses, that it is simpler and often cheaper to sell to Mr. Middleman and let him sell to the user. And the user often prefers to go to the middleman who sells a lot of all kinds of things rather than bother to buy from dozens of different men who grow a dozen different things. But, if you sell to a middleman, you must expect to receive less for your corn than if you sell it in small lots direct to the user, Billy Brad."

"But I do want more than thirty cents, Uncle Peter Henry," Billy Brad said doggedly.

"Yes, we all want 'more' for what we have to sell, and we all want to pay 'less' for what we have to buy," said Uncle Peter Henry. "But, after all, you are lucky to live in town, where you can sell to Mr. Jones himself. If you lived far away in the country and had a big, big cornfield, you would get even less than thirty cents for your corn, I expect."

"Why would I?" asked Billy Brad.

"Because so many people would handle the corn before it reached the house where it was to be cooked for dinner," said Uncle Peter Henry. "You might pick a great, big wagonload of corn and go to town with it, but the corn would have to go all the way to New York to get itself eaten. So you would take it to a man who makes a business of shipping corn to New York. Of course, he would have to be paid for his time and his trouble, because his wife and children have to have shoes and clothes and a house, too. And he has to have a building to do business in. And clerks, too, and packers, and teams and automobiles to haul the corn to the railway. So that money would have to come off the price of your corn.

"And -- and is that all?" asked Billy Brad.

"Oh, my, no!" said Uncle Peter Henry. "That is not nearly all. The railway has to have money, too. It must pay all its expenses. It must pay for the coal to make the steam that furnishes the power for the engines to pull the train. And the engineer has to be paid, too, because he has to eat and be clothed, and he probably has a wife and children also, and they need shoes and clothes and a house to live in."

"My!" said Billy Brad, for he had never imagined anything like this.

"And the brakemen on the train have to be paid, too," said Uncle Peter Henry; "and the men who keep the track in repair, and the men who load the train, and the men who unload it, and everyone who has anything to do with keeping the railway in good shape or with keeping the trains running. They all have to be paid! So all that comes off the price you get for your corn."

"I guess there wouldn't be much left for me, would there, Uncle Peter Henry?" asked Billy Brad.

"Not nearly as much as the ladies who pay sixty cents a dozen for your corn usually imagine," said Uncle Peter Henry, "because when the railway is paid for carrying the corn to New York, the corn is still far from the fire in the lady's kitchen. The shipping man in your town, who is called a commission man, does not send the corn straight to the grocery man. He sends it to another commission man. He sends it to a commission man in New York."

"And I know!" said Billy Brad quickly. "That man has a wife and he has to buy shoes for her, too, doesn't he, Uncle Peter Henry?"

"Exactly. He has all the living expenses and business expenses that the others have," Uncle Peter Henry agreed, "and your corn has to pay them. So you see, Billy Brad, a farmer does not get rich so quickly as we sometimes think he does. When we pay sixty cents a dozen for green corn at a grocer's we think, 'Oh, the lucky farmer!' But, really, he has to buy the seed and pay his hired men to plow and hoe and gather the corn, and then the commission man and the railway and the other commission man and the grocer all get part of the sixty cents. Very often they get the greater part of it. And if what the farmer is selling is fruit, or anything that decays soon, quite often the farmer gets no money at all. Sometimes the commission man has to tell him that the fruit could not be sold at all, because there was already too much fruit on the market. There are times when the farmer does not get any money but has to pay out money, to pay the railroad for carrying fruit that could not be sold when it reached the city."

"I don't like it that way," said Billy Brad. "I'd rather sell all my corn to my mamma for sixty cents a dozen."

Uncle Peter Henry laughed.

"And so would I, if I had corn to sell," he said. "I don't believe anyone loves the poor middleman. The farmer does not love him because he has to pay him, and the consumer does not love him because the middleman's expenses and profits are added to the price the farmer charges. Unfortunately, Billy Brad, the middleman seems, thus far, a necessity. Do you remember the funny restaurant you and I went to the other day?"

"Where we put the money in a slot and got what we wanted?"

"Yes, and carried the food and dishes to a table ourselves," said Uncle Peter Henry. "And it was a cheap place to eat, because we did that. There were no waiters whose wages had to be paid. We waited on ourselves. Where there are waiters, they have to be paid, and what they are paid is added to the cost of the pie and steak and bread and coffee we eat there. The waiter is a sort of middleman, you see."

Billy Brad looked at his beautiful field of corn. He was very human and he did wish he could get sixty cents a dozen for all his corn. He sighed a big sigh.

"There doesn't seem to be any help for it, does there, Billy Brad?"

"No," said Billy Brad. "Only -- only I wish I had lots and lots of mammas. For -- for because, if I had lots and lots of mammas, they would buy lots and lots of my corn, wouldn't they, Uncle Peter Henry?"