from Rotarian

Father

by Ellis Parker Butler

Quite early in the morning on the first Monday in August Mrs. Murch brought the automobile around to the cottage and tooted the horn several times to let Mr. Murch know she was ready to take him to the station, and Mr. Murch came out on the porch with his small gladstone bag. As he stood on the porch he was a remarkably fine figure of a businessman ready for his week's work, refreshed by a weekend at the lake. He set down the bag while he drew on his light topcoat. Doris and Dorothy had gone down to the car and were standing there waiting to say goodbye to him, and perhaps to give their mother some errand to do at the station village, but Ted stood near his father.

"I can carry your bag down," Ted said.

"No; it's too heavy for you," Mr. Murch said.

"I can carry it, papa," Ted said, picking up the bag.

The bag was pretty well loaded and it made Ted bend sideways to lift it but he started for the steps in a one-sided sort of way with the bag bumping against his right leg.

"Put that bag down!" ordered Mr. Murch sternly. "Didn't you hear me say it was too heavy for you? When I say a thing I mean it; don't you know that?"

"Yes, sir," said Ted meekly.

"Then I want you to obey me when I say a thing," said Mr. Murch. "And listen to me -- I want you to be a good boy this week, do you understand that? You do what your mother tells you to do."

"Yes, sir; I will," said Ted.

"All right; see that you do!" said Mr. Murch.

He turned to the boy and Ted threw his arms around his father's neck and hugged him hard, kissing him on the cheek, and Mr. Murch kissed the boy. "That's plenty," he said standing erect again. "I've got to go."

He picked up the gladstone and started down to the car and Ted went at his side. Mr. Murch kissed the girls and got into the car, and Mrs. Murch put her foot on the starter, which grated efficiently. The motor took hold.

"Oh, one minute!" Mr. Murch exclaimed. "Ted, go up to my bedroom and get that book I was reading; the red-covered book, 'Ethics in Business.' Hustle, now!"

The boy leaped away like an eager dog. He loped up the long incline to the porch steps, took the steps two at a time and presently was rushing back with the book in his hand.

"Thanks!" his father said and Mrs. Murch started the car and presently it was lost to sight behind the trees. The two girls stood waving their hands until the car went out of sight but as soon as the car started Ted was on his way to unchain his dog and that was the last the family saw of him until lunch time. He felt considerable relief that his father had gone to the city again; his mother was not nearly as masterful. When his father was about he felt that he had a master who must be obeyed, an autocrat whose word was law. His mother was different; with her he often argued questions of obedience and sometimes won. When his father said a thing it had to be done, but with his mother he was able to interpose reasons.

"Wear your Mackinac jacket, Ted," she would say.

"Aw, mother! Mother, I don't have to, do I? It's going to be hot -- I know it's going to be hot -- it's always hot when there's a fog first, mother."

"I don't want you to take a cold."

"Aw, mother, I won't take a cold! I want to go to the top of Mount Laurel with Joe, mother, and when it gets hot I'll just have to carry that old coat. I don't have to take it, do I?"

"Well --" Mrs. Murch would say doubtfully.

"It's always colder down here than it is up there. I don't have to take it, do I mother?"

"Well, all right; you needn't take it," she would say, "but don't take a cold."

When his father said "Wear your coat," he wore his coat. When his father said "Eat your beans," he ate his beans. When his father said "Go to bed," he went to bed. His father was that kind of father; when he said a thing Ted obeyed him.

Ted was like most boys -- he loved his mother but he admired his father. His father was a man but his mother, do the best she might, could be nothing but a woman. You love mothers but you admire fathers and are a little afraid of them all the while because they are autocrats and old and go out among men and are, in short, men among men. And men, when you come down to it, are men.

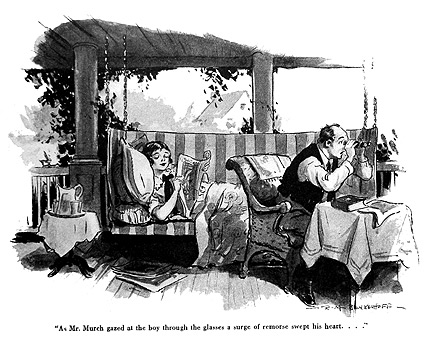

That week at Mr. Murch's particular lunch club the speaker was a remarkably fine man who had an important message to deliver and who delivered it in a telling way. He talked about sons and about fathers and about the influence of the father on the son, and he spoke with regret of the fact that fathers do not play with sons as much as they might. As a matter of fact many of the men at the luncheon felt, by the time Mr. Ganby ended his talk, that the most important thing in the world was for fathers to play with their sons. If the men at the luncheon had not been men they would undoubtedly have wept tumultuously to think how they had refrained from playing with their sons when they might have been doing so, and many an exporter-heart and wholesale-hardware-heart swelled with emotion and resolved to do better in the future. Mr. Murch's heart was a white-goods-commission-broker-and-banker-specializing-in-sheeting-heart and it swelled more or less, as it was expected to swell, but that afternoon Mr. Murch had an important deal on hand and his heart unswelled rapidly as he went back to the office and he forgot all about the importance of playing with his son until about three o'clock Saturday afternoon when he was sitting on the porch of the cottage at Laurel Lake, with Dorothy lying in the hammock and Mrs. Murch and Doris out of sight at the beach beyond the trees. On the table at Mr. Murch's side lay a pair of field glasses with their long shoulder strap -- glasses of the sort known as "bird-glasses." Mrs. Murch was interested in birds. Mr. Murch picked up the glasses idly and focused them on the spot where the little brook ended its meandering through the swamp and joined the lake.

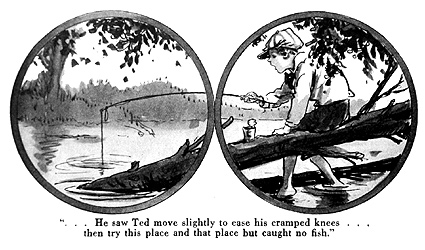

Crouched down on a moss-covered log to which he must have waded through mud knee deep, Ted sat on his haunches holding a beech whip over the water and from the tip of the whip hung a thread. All alone out there on the log Ted was fishing with a pin for a hook and a minor fraction of a worm for bait. He was fishing for "shiners" as long as his finger.

As Mr. Murch gazed at the boy through the glasses a surge of remorse swept his heart. He remembered what Mr. Ganby had said, but it had needed this sight of his lonely and neglected little boy to bring Mr. Ganby's words sharply home to him. He saw Ted move slightly to ease his cramped knees, and he saw Ted lean forward and gaze long into the weedy water before lowering his bent-pin hook into it. He saw Ted try this place and that place but catch no fish. He saw Ted give it up and lay the beech whip on the log and gaze off across the lake at the hills beyond, a poor, neglected, lonely little boy with no father to play with!

"Huh!" said Mr. Murch.

"What did you say, Edward?" asked Mrs. Murch.

"I didn't say anything," said Mr. Murch.

"I thought you said it was hot," said Mrs. Murch. "I think it is lovely and cool here."

Mr. Murch was still looking at Ted and his heart accused him of selfishness and indifference to the happiness of his boy. Ted, squatting on the log, pulled a wad of moss and rotted bark from the log and looked at the place from which he had taken it, poking the place with his finger. He pulled the moss to pieces, looking at it, and then hunched along on the log and took up his makeshift rod and tried fishing again, using something he had found in the moss as bait -- possibly a small worm, possibly a snail.

"Does Ted like to fish?" Mr. Murch asked, putting down the glasses.

"I don't think he ever speaks of fishing," said Mrs. Murch.

"I'm going to teach him to fish," said Mr. Murch.

Now and then when the subject had come up Mr. Murch had talked of the fishing he had done when he was a boy. Such talks had been while sitting on the porch of the cottage when other cottagers had visited the Murch cottage and the men were smoking their pipes or cigars.

"I certainly do remember going fishing when I was a boy," Mr. Murch would say. "As a matter of fact my folks could hardly keep me away from the river -- every Saturday as regular as clockwork until school closed and then practically every day all summer. Yes, sir! And we did catch some pretty good fish in that river, too."

"What kinds of fish were in the river?" the visitor would ask.

"Well," Mr. Murch would say, "we had perch and catfish and sunfish and pickerel and pike and bass --"

"Black bass?"

"Yes, black and striped too."

"Big-mouth black or little mouth?"

"Ah -- big mouth," Mr. Murch would say although, of course, he could not really remember that, not having known when a boy that there were two kinds of black bass and having forgotten now that he had never caught any black bass at all. Because fathers do not lie about the fish they caught when they were boys -- they merely mislay the facts, leaving empty places into which other facts crawl while they are asleep or in Chicago. Mr. Murch honestly believed he had been a tremendous fisher-lad when a boy. Nearly all men except those born and raised on tops of mountain peaks or in middles of sandy deserts do believe they were amazing fisher-lads when they were boys.

Mr. Murch when a boy had thought his father was the greatest and finest man in the world; Ted knew his father was.

That evening Mr. Murch asked Ted if he went fishing there at the lake.

"No, sir," Ted said. "Well, not much, anyway. Coupla times I went when Joe and Jimmy and Horace went but we didn't get anything but a coupla them red-eye rock bass -- little ones."

"Don't say 'them bass'; say 'those bass'."

"Those bass," said Ted obediently.

"What were you doing this afternoon, down there on that log?" asked Mr. Murch.

"Oh, down there on that log?" said Ted uncomfortably. "You mean down there on that log?"

"Yes, down on that log," said Mr. Murch. "Weren't you fishing?"

"I was just fooling around, sort of, said Ted, blushing. "I wasn't -- well -- just went down there."

"It's all right!" said Mr. Murch hurriedly. "I'm not scolding you. But next Saturday I'm going to take you fishing. I'm going to get a couple of rods and some tackle and you and I will go fishing."

"Oh, but --" said Doris and then was quiet.

"What now?" asked Mr. Murch looking at her.

"She just means," said Mrs. Murch, "that next Saturday is the day Mrs. Van Dorsen is having the water-picnic on the lake. But that doesn't matter at all, Edward; the girls can get another boat somewhere. Yes, you can, Dorothy; you can certainly find another boat somewhere. Very well, then, if you can't you can stay home from the picnic! I am not going to have your father think --"

The week was a rather unhappy one for Ted as far as his sisters were concerned for they blamed him for the boat, but they finally arranged to pack themselves into other boats and Ted certainly was happy in the thought of going fishing with his father. He was joyous with pride and told all his young friends.

"My father is going to go fishing with me," he said to all of them. "I bet he knows how to fish better than your father does."

"Aw, he does not! My father knows better than your father does."

"He does not so! My father fished all the time when he was a boy," Ted bragged. "He fished every day."

That Friday night Mr. Murch was awaited by a mighty eager young man. Ted was down at the foot of the slope below the cottage half an hour before his mother started for the station in the car, and he opened the door of the car and reached for the paper-wrapped bundle almost before the returning car stopped.

"Oh, boy!" he cried joyously as he saw the ends of the joints of the rods that had worked through the paper.

"Just go easy with that, son, until you get to the cottage," Mr. Murch said. "There are hooks and things in that bundle; I don't want you getting them stuck into you."

He did let Ted carry the bundle to the cottage, however, and he felt better and more chummy already. He realized that he had made a big mistake in not being a boy with his boy.

"If there's anything we haven't got in this bundle in the fishing line, old son," he said merrily, "I want somebody to tell me. When we fish we fish!"

"Oh, boy!" Ted exclaimed. He was thoroughly excited.

After dinner when the table was cleared Mr. Murch and Ted opened the bundle. There was a great amount of work to be done, it seemed, to prepare for Saturday's sport. The fishline was on spools and it had to be put on the reels. At first Mr. Murch was going to insist that Ted hold the spools while he turned the reel handles himself but he remembered that he was being his son's playfellow and he let Ted do the reeling. This made Mr. Murch feel fine, and when Ted got a snarl in one of the lines and Mr. Murch untangled it with a few deft pulls here and there Ted knew that his father was unquestionably the greatest man on earth.

The rods, although but cheap ones, were beautiful, too, and the reels were lovely. Mr. Murch had bought a good assortment of fishing tackle in addition to the rods and reels and these had to be sorted out and put into empty cigar boxes. There were imitation minnows with dozens of hooks strung on their sides and attached to their tails in gangs of four; there were white plugs with gangs of hooks on them; there were imitation frogs and brass spinners and silver spinners, all with gangs of four hooks.

"Gee!" cried Ted. I bet we're going to get some whopping big ones!"

Mr. Murch did not get the inference at all, which was that no one who fished in that lake dared go after as big fish as Mr. Murch was evidently going to catch. No one dared use such hooks or such big spinners or such big artificial minnows. Being less expert than Mr. Murch's boyhood fishing had made him, none of the others dared fish for fish that needed such extra heavy fishline or snell hooks with quadruple twisted gut snells.

Mr. Murch was properly proud of the fishing tackle and he explained it piece by piece, telling Ted what the salesman had told him about it.

"This," he said, showing Ted a most peculiar construction that was painted red and yellow with black spots, "is what they call a Oomtowakka Wiggler. It gets the big ones; it gets them when the other fellows don't get even a bite. I got two of them; one for you and one for me."

"Oh, boy!" Ted exclaimed.

"Don't get your fingers stuck on the hooks," said Mr. Murch.

"No, sir," said Ted.

"Ouch!" said Mr. Murch, getting one of his fingers stuck on one of the hooks.

The next morning Ted could not sleep and was up at an hour when the sun was still in bed and as he had nothing else to do he got the electric torch and went out and gathered in a few "night-crawlers" -- the big fat angle-worms that hide by day, going down where no spade can reach them. He nabbed twenty of them before the sun arose and drove them to their holes and he put them in a can and stood them on the edge of the porch. Night-crawlers were what the big boys used when they fished in the lake; they caught sunfish and red-eye rock-bass with them when luck was with them and the pesky perch did not clean their hooks the moment they were put into the water. He felt rather ashamed to be bothering with such a babyish thing as worm-bait when his father was going to take him fishing but he felt the fishingest he had ever felt and he had to be doing something fishy and there did not seem to be anything else to do until his father appeared.

Mr. Murch appeared just before breakfast, standing on the back porch for a wash-off in the tin basin, and he hailed Ted.

"Hello there, chum!" he called cheerily, as one pal to another. "Great day for our fishing!"

"Yes, sir," said Ted, and he was glad to hear his father say it was a good day for fishing because he had been wondering whether his father would go fishing that day. It was evident, however, that the fellows at the lake knew nothing whatever about real fishing; a real fisherman like Ted's father knew the best sort of day, and a day that was brilliantly clear and without a sign of a breeze was evidently the best sort of day. Ted stored that knowledge away for future use -- a still and bright day on which the sun would beat down like fire was the best day for fishing.

Mr. Murch ate his breakfast in comfortable leisure and Mrs. Murch took her time in preparing a lunch for she prepared the picnic lunch for Doris and Dorothy at the same time. Mr. Murch was in no hurry. He drove to the station village for the morning paper and read it after his return, and by ten o'clock he was ready to go fishing. He carried one rod and one oar of the boat and Ted carried the other.

"What's that?" he asked as he saw the tin can that Ted carried.

"Well, I got some worms," Ted said. "I was up pretty early this morning and I got some worms. I thought maybe --"

"Sure! That's all right," said Mr. Murch genially. "Maybe we'll do some worm fishing, too. That's the right idea, Ted; always be prepared for whatever may happen and then -- Say! I forgot my pipe! Run back and get my pipe, will you, son? And my tobacco. And say -- hey, Ted! -- get a handful of cigars."

Ted got them.

"Look here," Mr. Murch said, "we can't have this dog with us. We can't have a dog piling all over the boat. Take him back and tie him up."

Ted took the dog back and chained him and the dog stood at the end of his chain and howled his sorrow. He did not seem to care much for son-and-father activities, this being the first time he had been forbidden to accompany Ted when Ted went away from the cottage, but a lively dog is not a good fishing companion, particularly not when the bottom of the boat is liable to be full of Oomtowakka Wigglers and other fish-snares with many wicked hooks. A man can't be all the time taking hooks out of dogs if he is to enjoy a chummy fishing excursion with his son.

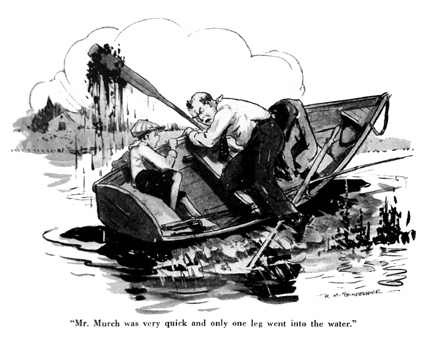

Mr. Murch rowed the boat while Ted sat in the stern. Mr. Murch did not row very well, not having used oars for some forty years and the pickerelweed near the shore was standing high out of the water. The third time the left oar jumped out of the rowlock Mr. Murch stood up to take off his coat and the boat tipped suddenly. But Mr. Murch was quick and only one leg went into the water although the shank of that one was really rather badly skinned on the edge of the boat.

"Damn it!" said Mr. Murch quite seriously as he sat down suddenly on he box of tackle he had on the seat. "You noticed that, did you, Ted? Never stand up in a boat -- never!"

"No, sir," said Ted. "Do you want, I should row, papa?"

"I will row," said Mr. Murch. "I'll get the hang of it again in a minute. I used to be a dandy at it, but of course I haven't rowed for forty years or so. A man gets out of practice."

"Yes, sir," said Ted. "Maybe you'd better put your coat up on the seat; your cigars will get all wet."

They were all wet already, so Mr. Murch spread them on the other seat where, later, when he moved over to that seat, he sat on them. He rowed well out into the arm of the lake and stopped there. Ted looked over the side and saw the pickerelweed, huge forests of it, reaching up to just beneath the surface of the water. He saw, down in among the green, the little perch loafing in the shade of the pickerelweed leaves.

"We'll try it here," said Mr. Murch. "This looks like a good bass place."

"Yes, sir," said Ted, all his former notions of good bass places vanishing. He would have said this was a horrible place for fishing, one of the places where perch cleaned your hook instantly and you never caught anything but sunfish and then not until just before sunset. But father knew; father had been a great fisherman.

"We'll try the Oomtowakka Wigglers first, son," Mr. Murch said, putting his jointed rod together, "because I have great faith in them."

So he put his reel on the rod wrong side to, so that it unreeled when it should reel up, and reeled up when it should unreel. He then put a float or bobber on his line with the red end down when Ted had always suspected that the dark green end was meant to be down least the red scare the fish. This was evidently one of the fallacies of the ignorant amateurs. So, too, it seemed was the notion that a bobber was not to be used when a patent trolling or casting bait was used, because Mr. Murch used one. Below the bobber Mr. Murch then fastened a small lead sinker. Ted did the same, watching his father closely in order that he might space his bobber and sinker in the proper way as an expert spaced them. On the end of his line Mr. Murch then tied the Oomtowakka Wiggler, and on the end of his line Ted tied an Oomtowakka Wiggler.

"There!" exclaimed Mr. Murch. "Now for a fish!"

He raised his rod in the air and swung the Oomtowakka Wiggler back and forth a few times at the end of its line and made a violent over hand cast. The reel whirred; the Oomtowakka Wiggler seemed to have disappeared utterly.

"It got caught in your coat, I guess," Ted said, and it had indeed got caught in Mr. Murch's coat. The Oomtowakka Wiggler had five gangs of hooks, four hooks to the gang, and some eighteen of these twenty hooks had bit deep beyond their barbs into the back of Mr. Murch's coat. It was then that Mr. Murch moved over to the other seat and sat on the cigars. Eventually Mr. Murch cut three square inches out of the back of his coat with his penknife and whittled the shreds from the hooks. He then cast the Oomtowakka Wiggler into the lake again, this time having better luck, for it sank deep and engaged a pickerel weed near the roots.

"Cuss it!" said Mr. Murch as he jiggled his rod and tried to free the Oomtowakka Wiggler.

"It's pretty weedy here," said Ted. "It's mostly all weeds all around here."

"Come out of there, you!" exclaimed Mr. Murch, giving the line a violent pull. The line came but the Oomtowakka Wiggler remained at the bottom of the lake.

"Did you have a fish on, papa?" asked Ted.

"I think we'll troll awhile," said Mr. Murch. "You can use that Wiggler if you want to, but I'm going to try one of these brass spinners for awhile. These spinners get some big ones."

"You can use my Wiggler if you want to," said Ted generously.

Mr. Murch, however, was searching in his box for a brass spoon and he made no mistake in tying to the end of his line this time. He put twelve hard knots in it. He then lowered the spoon over the side of the boat and reached for the oars, but he was on the wrong seat and had to change seats again. Ted kept his Wiggler out of the water. Mr. Murch took the oars and started the boat slowly and as it gained headway he heard the reel whir with sudden vehemence.

"I've got him!" he cried and grasped his rod. He turned the handle of the reel rapidly and the line unwound. He took the reel in the other hand and used his left hand for the reel and the line grew taut, but it did not jiggle as a line does when a fish is snared.

"I guess you've got a weed," said Ted.

"Huh!" said Mr. Murch for he had indeed got a weed and a good one. He laid the rod in the boat and pulled on the line -- pulled gently -- and the boat backed up to the weed, backed over it, went on, stopped. Mr. Murch pulled. The weed, becoming hopeless, yielded and came up by the roots, bringing a wad of mud that clouded the water around it. Mr. Murch leaned over and disengaged the brass spinner's hooks and dropped the spinner back into the water. It immediately attached itself to another weed.

"It's pretty weedy here," Ted ventured to say.

Mr. Murch pulled that weed up by the roots.

"If I owned this lake," he said, "I'd rake these weeds out of it."

He laid the brass spinner on the seat in front and looked around the lake. In many places the pickerelweeds stood above the water in great fields but far over to the north, near the shore there seemed to be clear water.

"Don't put your line in yet, I'm going to row over there," he said.

"All right," Ted said obediently.

Mr. Murch rowed to the far side of the lake. Here the woods arose abruptly from the edge of the lake, climbing the hill, and there were no weeds in the water until fifty yards from the shore.

"This is something like it," said Mr. Murch cheerfully. "We'll troll here awhile."

He put his spinner in the water and fed out quite a little line and took up the oars.

"You can put your Wiggler in," he said.

"Yes, sir," Ted said and he put his Wiggler overboard. It went to the bottom like a rock, assisted by the lead sinker. Mr. Murch pulled on the oars and almost immediately his reel began to hum again and Ted's reel joined it in singing. Mr. Murch had made one mistake in guessing he had a fish and this time he was more cautious.

"I don't suppose I've got a fish already!" he said, but hoping he had.

"No, sir," Ted said. "I guess there's a lot of snags in here. I guess the trees fall into the water and make snags here. I guess maybe we've got some snags."

"I'll just back up," said Mr. Murch and he backed the boat. At the third jerk he gave his line the line parted above the bobber.

"Do you want I should jerk mine up, too, papa?" asked Ted.

Mr. Murch looked at Ted's taut line.

"Jerk it!" he said. "Here, give it to me, I'll jerk it."

He jerked it and the line came up, leaving the Oomtowakka Wiggler at the bottom of the lake.

"This is a swell lake to fish in, I don't believe!" said Mr. Murch with bitter irony. "I'm going to row around into that other arm."

From the cottage the other arm of the lake seemed but a stone's throw distant but it was in fact much farther than that. It was far if one rowed a direct course through the pickerelweed, but Mr. Murch chose to follow the clearer water by the shore and one point followed another. He took off his vest and the perspiration rolled down his face and the sun now beat down like something living and virulent. He laid his hat aside and bent to the oars and his moist and unaccustomed hands blistered at the tops of their palms, and he tore his handkerchief in two and wrapped the halves around the handles of the oars. The boat moved slowly. Mr. Murch set his mouth in a hard line and rowed grimly.

"You had better row out a little, papa," Ted said now and then and, when Mr. Murch turned his head he then saw he was rowing straight into the shore. They rounded point after point; now and then Mr. Murch held both oars in one hand while he wiped his forehead with the sleeve of his shirt. Then he rowed on. "You had better row out a little, papa; there's a dead tree there."

They reached, around the final point, the other arm of the lake and here, where a huge maple tree extended a branch over the water, Mr. Murch ran the nose of the boat into the shore. There was shade here, almost the only shade on the lake.

"We'll try it here," said Mr. Murch. "This looks like a good place to me."

"Yes, sir," said Ted obediently. "What shall we fish with?"

Mr. Murch looked into the cigar box and selected two of the weird fishing appliances he had bought. One was the green and yellow thing with black spots; the other was an aluminum article of torpedo shape, painted white below and green above.

"We will try these," said Mr. Murch and he passed the aluminum curiosity to Ted.

"Are we going to troll?" asked Ted.

"We are going to fish right here awhile," said Mr. Murch. "I think this is a good place for bass."

"Yes, sir," said Ted obediently, although he knew no bass could have been there since the last convulsion of nature, perhaps some eight million years before, had made this a shoal with a muck bottom, and he tied the aluminum incongruity to the end of his line. He waited then for his father to show him the right way to fish for bass with this sort of instrument. Mr. Murch ran out a little line, swung his green and yellow affair some four feet beyond the boat and let it sink. It settled calmly into the mud, drawn downward by the sinker, and was lost to sight. The green and red bobber floated calmly on the surface. Mr. Murch took out his pipe and filled and lighted it, felt gently of the top of his head, looked at the blisters on his hands and practically ceased to exist. Ted put his aluminum toy in the water and the sinker drew it down but it was lighter than Mr. Murch's tricolored error of judgment and did not sink entirely into the muck. It could still be seen and now and then during the afternoon a small yellow perch of fingerling size swam up and examined it with amazement and then swam away to tell its folks what it had seen. None of its family ever believed it.

About one o'clock Mr. Murch and Ted ate their lunch and drank cool water out of a thermos bottle and about two Mr. Murch made himself a pillow out of his coat and went to sleep in the boat. Now and then Ted raised and lowered his line, letting the aluminum lure rest on a different place in the mud. He kept very quiet so that he might not disturb his father's sleep. He watched a colony of apple-seed bugs that wiggled about on the surface of the lake under the lee of the boat, and he caught one and let it dry and it flew away. The seat of the boat grew harder and harder and Ted moved from hip to hip. He turned and looked out over the lake but there was not another boat in sight. He looked up into the maple tree. He looked down at his toes and tried to see how far he could cross his big toes over the toes next to them. It was the longest afternoon he had ever spent and the dullest and most uncomfortable. About five o'clock his father awakened, sat up and looked around.

"Hello!" he said. "Caught any fish?"

"No, sir," Ted said.

"That's funny," Mr. Murch said. "I've been asleep, I guess."

"Yes, sir," Ted agreed.

"Well, there don't seem to be any fish here," said Mr. Murch. "My word, this afternoon certainly has flown! My, but my hands are sore!"

"Shall I row?" asked Ted.

"You might try it awhile, anyway," said Mr. Murch.

Ted rowed to the homeward end of the arm and then directly toward the home cove. Now and then he looked over his shoulder to get his direction and when he was near home he let the boat stop between a white birch clump on one shore of the lake and white rock on the other.

"Do you want to fish any more, papa?" he asked.

"Do you?" asked Mr. Murch.

"Well, we haven't got any fish yet," said Ted rather wistfully. "I guess about now is about the best time, maybe. I guess this is about as good a place as any place, maybe."

"All right, son," said Mr. Murch cheerfully. "Try it is the word!"

"I guess I'll use a hook," said Ted.

"Anything you want to use," agreed Mr. Murch.

"I guess I'll use a sort of little hook," said Ted, and he took a "sort of little hook" from the pocket of his shirt and put it on the end of his line. The lead sinker he removed. He turned the bobber the other side up. He dug a worm from his can and took a reasonably small section of it.

"I'm going after bigger fish," said Mr. Murch merrily, and he put one of his four-snelled hooks on his line. It was a big hook and it took a big worm. That sized worm squirmed like a snake when he lowered it into the water.

Almost immediately Ted drew in a red-eye rock-bass as big as his father's hand.

"I got another little hook," he suggested.

"I'll use this one," his father said, trying the other side of the boat.

The next Ted got was a sunfish -- a "croppie" or "goggle-eye" -- but not a big one. He put it back and caught one as big as his rock bass instead. He caught two more and one perch big enough to eat. He felt ashamed of himself because he was catching so many while his father caught none.

"Maybe your bait is too big," he said. "Maybe it scares them away."

"I'm going to get a big one," said Mr. Murch.

"I guess maybe there aren't any big ones here," said Ted. "Mostly they don't get any big ones but pickerel in this lake, and they have to skitter for them."

"Have to what?" asked Mr. Murch.

"Skitter," said Ted. "They skitter over the top of the water with a big live shiner and the pickerel jump for them."

"Oh!" said Mr. Murch.

"Except sometimes they get a black bass over by that white rock when they've got shiners or frogs for bait."

"Oh!" said Mr. Murch.

"I've got another one, I guess," said Ted as his bobber went under suddenly. "Gee! I guess it's a big one! Oh, boy! Big old red-eye! Do you want to pull it in, papa?"

"Maybe I'd better, if it's a big one," said Mr. Murch.

"Oh, boy! It's a black bass!" cried Ted. "Here -- you pull it in."

He handed the rod to his father. He felt sorry for his father, who could catch no fish. Mr. Murch took the rod; he put his thumb on the reel and gave a mighty jerk; the bass at the same moment made a rush away from Mr. Murch; the line, bobber and hook flew up in the air. For a moment Ted looked at his father aghast.

"I guess I didn't have it hooked very well," he said meekly. "Do you want to go home now?"

"It's getting on toward dinner time," said Mr. Murch.

"I guess maybe it wasn't as big as I thought it was," said Ted. "I guess it was only a red-eye, anyhow."

When they reached the cottage Mrs. Murch was waiting at the top of the porch steps.

"Well, well! My fisher-boys!" she exclaimed. "Did you have a good time?"

"Did we have a good time!" laughed Mr. Murch in true son-and-father style. "I'll say we did!"

"Did you get any fish?"

"We got some," said Ted. "We got six."

"Won-der-ful!" cried Mrs. Murch. "We'll have them for dinner -- our own fishermen's fish!"

"Yes, mam," said Ted.

"Emma," said Mr. Murch, "where do you keep that stuff you put on to cure sunburn? The top of my head is raw as a boil."

Ted put his can of worms behind one of the posts that held up the porch and went around to the back to wash up for dinner. He listened during the dinner while his father told with well-simulated enthusiasm of the fun they had had, but he looked at his father more than he had looked at him in all his life. He could not keep his eyes from his father's face. He felt glad because his father had gone fishing with him but he felt uneasy, too, as if he had lost something and did not know what it was but wished he could find it again. It was not much he had lost, probably; it was merely his belief that his father was wonderful in all ways. He still believed his father was wonderful in all ways but one; he really could not believe his father was a wonderful fisherman.

"I think it is good for you and Ted to be together more than you have been," said Mrs. Murch when the rest of the family was in bed.

Mr. Murch puffed his pipe thoughtfully and considered this. He considered it so long that Mrs. Murch repeated her statement.

"I said I thought it was good for you and Ted to be together more than you have been," she said.

"Yes," said Mr. Murch slowly; "it is going to be a great thing for me; I can see that."