from Century Magazine

The Sectional House

by Ellis Parker Butler

Ever since I was old enough to pay my first instalment in a building and loan association, I have had theories regarding the proper building of houses, which I intended to put into practice. Unfortunately, I have always been obliged to draw out my money before the shares matured; but as soon as I withdraw from one association, I begin again with another. Some day I hope to mature some shares. Martha, however, does not think I shall.

Martha is my wife. Both of us were born and raised in Wautuska, which is undoubtedly the fairest Iowa town into which a building and loan agent ever ventured. One thing that first drew me to Martha was the similarity of our ideas regarding houses. We both believed that the ideal method of building a home was to start small and let it grow. When we looked about upon our married friends, we disapproved of the homes they had built. Some of them built houses that were so large as to be sources of continual inconvenience; others built snug little cottages for two, and, as soon as they became accustomed to them, had to tear them down and build larger houses.

Martha and I agreed that the best way was to build a small house on a large lot, and then, as needed, add to it. Thus each year would also add to its associations. There is something charming about a house that is built in this manner. A gradually accumulated house has a great deal of character. I may mention the Squirrel Inn, of which Mr. Stockton wrote such a pleasant story, as an example. It was all character.

Unfortunately, my building-and-loan shares never reached a point that permitted me to carry my theories into execution, and when Martha and I decided to marry, we feared that, after all, we should be obliged to rent an ordinary ready-made house, when one evening we chanced on the advertisement of a sectional house. We read the advertisement carefully, and we knew the sectional house was what we had been waiting for. The next day I stopped at the local branch office of the Sectional House Company. The man in charge, who also sold sewing-machines and incubators, was very polite, and I need only say that the more I saw of the house the more infatuated with the system I became. The principle was that of the sectional bookcases of which every one has heard. It was, the attendant explained, a collection of units. In this case a unit meant one room.

To begin with, you bought as many units as you needed or could afford. Each unit fitted exactly into every other unit, and there was a sectional roof. Then, as more rooms were needed in your house, all you had to do was to send word to the agent of the Sectional House Company for them. Thus you could continue for years with a small cottage, or in a few days you could increase your house to the dimensions of a summer hotel.

Of course the system, to work well, required that all the units must be of one size and shape, and the resulting house was somewhat rectangular; but as there was a variety of veranda units, the stiffness could be alleviated. The terms were liberal. It was only necessary to pay a small amount down; the balance could be paid in monthly instalments.

Martha and I began with five units -- a parlor, a kitchen, a bedroom, a dining room, and a bathroom. We placed the order with the agent, paid our initial instalment, and were married.

I was very busy during the weeks just preceding our wedding, and did not have time to visit Wautuska, the suburb of our little Western town, where our home was to be; but I gave the Sectional House Company's agent the location of our lot, with orders to deliver the house there, and Martha and I commissioned Wills & Boggs, the decorative furnishers, to have the house completely furnished before our return from our wedding trip.

Our tour was enlivened by our eagerness to see our little home and to begin life there. We could not reach Wautuska by daylight, as we could not make the proper connections; and as the way from the station was rather dark, we found our lot with great difficulty.

"And now," said Martha, "for our home!"

She pushed open the gate, and we hurried in; but right before us and across the walk was a large, square, box-like affair. I groped about it with my hands, and presently discovered a door.

"Well," I said with some chagrin, "this is our house! I had no idea they would put it so far forward on the lot. I must have forgotten to tell them."

"It is too bad," said Martha, "but we can have it moved back tomorrow. The thing to do now is to get inside. I am dying to see how it looks."

I fumbled at the lock several minutes before I discovered that the door was not locked. I considered this very careless, but said nothing, and we entered. I struck a match, and Martha uttered an exclamation of surprise. We were in our bath-room! I tried to light the gas. It would not light. I was sure I had instructed the gas company to turn on the gas.

"It is evident," I said, "that the man who delivered these units did not know his business. No one would want a bath-room as an entrance to a house. It would be an insult to his guests. But the thing to do now is to find the parlor, so that we can have a light."

With that I opened the door opposite to that by which we had entered, and stepped across the sill. The next moment I suffered a severe jar, and found myself sitting on the damp earth. I had fallen into my own cellar. It was clear that my bath-room unit was not closely connected with the other units.

I managed to climb out of the cellar, and I assured Martha that I was unharmed, and we began looking for the rest of our house.

We found it gradually. It was scattered about our lot in single units. The parlor was in the northwest corner, the bedroom was down by the alley fence, the dining room rested against the big elm tree, and the kitchen was some sixty feet away.

Every few steps we fell over units of roof or units of porch, and it came to me that I had purchased the units as units, and that to consolidate them into an e pluribus unum, if I may use the Latin, was the purchaser's duty.

Every few steps we fell over units of roof or units of porch, and it came to me that I had purchased the units as units, and that to consolidate them into an e pluribus unum, if I may use the Latin, was the purchaser's duty.

But the decorative furnisher had done his work well. The units were beautifully decorated, and all the furniture was in place in each unit. We had a beautifully complete, though scattered, little home, and every room was ready for use, except that the gas and plumbing were not connected, and that the parlor unit was lying upon its side.

The parlor was rather puzzling, for as we stood in it, with the wall-paper under our feet, a nicely tinted ceiling was at one side, while our Wilton carpet formed the opposite wall. I think I laughed, but later I had to pay Wills & Boggs an extra charge of three dollars because the carpet-layers had been obliged to use step-ladders. But our bedroom was beautiful, and we were tired enough to sleep well.

The next morning Martha found it a little unhandy to have the kitchen so far from the dining room; but she went to work cheerily, and my heart was very full as I sat on a porch unit and watched her running back and forth among our house, now into the kitchen, now across the lot to the dining-room, then down by the alley fence to the bedroom to make our bed, or climbing into the parlor window with her broom and a ladder to sweep the floor.

That day I had a safe-mover and a plumber up from the village, and we assembled our units into a complete house.

We had, later, many opportunities to congratulate ourselves on our sectional house. As our family grew, we added more bedroom units, and we were so cozy that a number of our friends began housebuilding on the unit plan in our neighborhood.

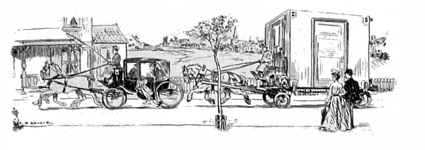

There were a few annoyances. We added a spare bedroom unit one autumn, and my sister Sarah soon after decided to pay us a visit. We gave her a hearty welcome, and installed her in the room. Unfortunately, I had let several payments lapse on it, and on the third day of my sister's visit the Sectional House Company's collector came and insisted that he must either collect the money or take back the spare bedroom. As Martha had no money at hand, the collector loaded the bedroom unit on a wagon and drove off with it. I should not have felt so chagrined if Sarah had not complicated matters by refusing to vacate the room. I found her, angry but comfortable, some eight hours later, still occupying the bedroom unit, which was then standing in a freight-car, ready for the arrival of the next train.

That spare bedroom was a continual bother to us. The greater part of the time it was vacant and that led to a serious quarrel with Southeby, one of my best friends.

Southeby has the lot next mine, and one day he came to me saying he had received a telegram from his uncle who wished to spend a week or two with him. Southeby hoped to be remembered in his uncle's will, and as he had no spare bedroom, he had wired to the Sectional House Company, only to find that the company was out of bedroom units, and several months oversold. Knowing my spare bedroom unit was not in use, he asked me to lend it to him for a few weeks. I was glad to accommodate him, and the next day he came for it.

A month later Southeby had not yet returned it. I had always returned Southeby's lawn mower promptly, and I thought Southeby should have done the same with my bedroom. I hinted as much to him, but month followed month, and I began to think he had no intention of returning it. I wrote him a sharp letter, asking him if he intended to keep it forever. At length I told Martha that I would get the bedroom myself, and she agreed with me. I do not wonder that Southeby disliked to return that unit. Such a condition as it was in! Since then I have time and again refused to lend any of my house.

On the whole, however, I have not regretted becoming a sectional-house owner. Of the newfangled folding units I have been wary. They do not appeal to me. It may be convenient to have a house that can be folded up and stored away in the barn when you are out of town, but it is annoying to have a room fold up when you are in it.

Our house is now hardly larger than when Martha and I began housekeeping. One by one our children have married and started out for themselves, and to each we have given a few units of the old home as a sort of nest-egg. Martha and I are getting old now. We have not accumulated much wealth, but I hope we may never be so poor as to be unable to give our grand children a unit or two from the old house when they marry.

As for us, we expect in our old age to become members of the Wautuska Old Folks' Sectional Home. It may seem strange that we should wish to end our days in an institution, but the Wautuska Home is not like others. One does not have to part from the rooms made holy by the memories of the past; he takes his old home with him, and its units are added to those that are already there.