from American Girl

Jo Ann and the Last Straw

by Ellis Parker Butler

On the first day of September Jo Ann returned from Camp Minnedawa. She had had a glorious summer there and she was as brown as a berry and as full of pep as a Mexican jumping bean. The first thing she did was to kiss her mother and hug her ecstatically; the second was to ask, "Where's Rags? How is he?"

"Jo Ann," said her mother, suddenly serious. "I hate to have to tell you. He's gone!"

"Mother! Gone?" cried Jo Ann with horror. "Do you mean he is dead, Mother?"

In every letter Jo Ann had written from camp she had asked her mother how the pup was. In every letter to Jo Ann her mother had replied that the pup was fine and well. Jo Ann, great as was the fun she had been having at Camp Minnedawa, had hardly been able to wait to get home and see the pup. She had counted the days.

In June, just before Jo Ann had gone to camp, Wicky Wickham and Ted Spence had bought the pup for Jo Ann and Tommy Bassick, one half the pup to be Jo Ann's and one half to be Tommy's. Ted had made a kennel for the pup.

He had made a door at each end or the kennel, one door to point toward Tommy's yard and one door to point toward Jo Ann's yard. Over one door he painted "Sport" because Tommy insisted that "Sport" was to be the dog's name, and over the other door he painted "Rags" because Jo Ann declared the dog's name was to be "Rags". Ted wanted to satisfy both.

The kennel was to stand exactly on the line between Tommy's yard and Jo Ann's yard, half in each yard, but the trouble was that Tommy's yard came down to Jo Ann's yard in a steep terrace with but a foot or two of level ground at the bottom. The result was that the pup was actually in Jo Ann's yard all summer. Jo Ann's mother had written her, "It is quite as if the puppy were all yours. With the kennel at the bottom of the terrace I have all the care of the pup. He can't go up into the Bassick yard because he is tied to the kennel, and Mrs. Bassick can't very well come down the terrace to feed the pup."

"No, I don't mean the pup is dead," Jo Ann's mother said. "I'm afraid he has run away or been stolen. He was all right yesterday morning but when I came out to feed him last night he was gone -- rope and all. It's very queer."

"Oh!" exclaimed Jo Ann in an odd tone, and in the next breath: "Mother, is Tommy Bassick home from camp yet?"

"He got home yesterday -- yesterday afternoon," said her mother.

"Oh!" said Jo Ann in quite another tone. "So that's it, is it? Well, I'll see about that! He can't steal my dog! Not my half of the dog!"

"Jo Ann! Wait a minute! Come back here!" her mother called, but Jo Ann was already scrambling up the terrace into Tommy Bassick's yard like an agile goat. In her mind she had no doubt that Tommy Bassick had taken the pup. It would be just like him, she thought, to do it.

"I'll be back, Mother," she shouted from the top of the terrace. "Take my things into the house, please." Her mother sighed. She had hoped Jo Ann would come home less tomboyish but Jo Ann had gone up that terrace in a way that was amazingly athletic, with one long run across the yard and a couple of leaps up the steep affair. At the top of the terrace Jo Ann paused to look and listen. She neither saw nor heard either Tommy or the puppy.

"Rags!" she called. "Here, Rags! Come, Rags!"

From behind a corner of his house Tommy Bassick poked his head. He was quick and he drew back his head promptly, but Jo Ann saw him and was after him instantly. She dashed for the corner of the house and then reversed suddenly and ran the other way. She knew he would make for the kitchen door and she meant to head him off before he reached it, and she did. They came together at the kitchen steps as Tommy was starting up them, and by a flying leap Jo Ann managed to throw her arm around one of his feet. They thudded together on the steps and Tommy twisted around.

"Aw, say! What's the matter? What did I do now?" he asked, trying to pull his foot from Jo Ann's embrace.

"You know what you did," Jo Ann said, hugging his foot tightly. "Where's my dog?"

"Let go my foot," said Tommy. "I don't know where any dog is. If you mean our dog, I haven't even seen him since I got home."

"I mean my dog," said Jo Ann.

"You don't own a dog -- you only own half a dog. Half's mine. If you've gone and lost my half of that dog you'll have to pay for it. So you'd better go out and find him."

Jo Ann, looking annoyed, cautiously released Tommy's foot. "Tommy Bassick," she said, "you took Rags, and you know you did. You've no right to take him away from the kennel. I want him back this minute or you'll be sorry."

"I don't know any dog named Rags," Tommy said, rubbing his leg where it had hit the edge of a step. "If you mean the dog named Sport, that I own half of, I tell you I don't know anything about where he is. I really don't."

Jo Ann rubbed her own knee. She sat on a lower step and looked up at Tommy, almost inclined to believe him.

"Honest?" she asked. "Are you sure? Cross your heart?"

"Honest! That's the honest truth. I haven't seen him since I went to camp last July. That's the truth, Jo Ann."

"He's gone," Jo Ann said. "I thought you took him and it was the last straw. I wasn't going to stand any more nonsense from you. Did you hurt your leg?"

"Yes."

"Well, I hurt my knee worse, so you needn't complain. What do you suppose happened to Rags?"

"To Sport? I know what happened to him, I guess," Tommy said, still rubbing his leg. "There was a piece in the paper last night that said a lot of dogs were being stolen. It said it was about time the police or somebody did something about it. It said over a hundred dogs had been stolen in town. It warned people not to buy dogs from dog-peddlers, because they were probably stolen dogs."

"Is that so? Come on, then. You've got to come with me; you own half the dog," Jo Ann said.

"Where?" Tommy asked.

"The police, of course," Jo Ann said. "You don't think I'm going to let anybody steal my half of a dog, do you, and not do anything about it? I'm going to report it to the police right away. Do you know where the police place is -- they call it Headquarters, don't they? Get your hat and come on."

"I don't wear a hat," said Tommy. "Police Headquarters ought to be in the City Hall, I should think. Which way shall we go?"

"Across lots," said Jo Ann, "it's shorter. We must hurry."

"Wait till I tell my mother I'm going," Tommy said. "Do you want me to get something to rub on your knee?"

"No," said Jo Ann. "A bump's nothing. Hurry up if you're going to put arnica on you."

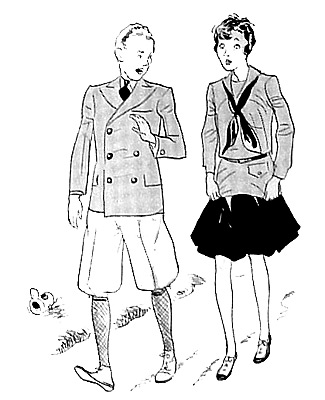

When Tommy came out again Jo Ann led the way. They went out the back way because thus they could cut across vacant lots to the main part of town. Jo Ann noticed that Tommy had taken time to brush his red hair; he had wet it sopping wet and smoothed it flat. Then she saw that his hands were suspiciously clean as if he had just washed them. Then, although she seldom noticed such things, she saw he had changed his clothes and was now wearing what must be his best suit.

"You put on a different suit," she said. She was wearing her roughly handled camp uniform. "What did you do that for?"

"Well, I was going downtown with you," Tommy said, blushing. "I didn't think you'd want me to look all mussy."

"Oh!" said Jo Ann. "And I've got on this old camp rig."

"You look all right," Tommy said. "You look fine."

He blushed again. Or perhaps it was the same blush. Jo Ann could hardly believe her eyes and ears -- Tommy Bassick had actually changed his suit to go downtown with her! She suddenly realized that one of her sneakers had a hole in the toe. It was probably the first time Jo Ann had ever given a thought to her wear except to think that all clothes were a nuisance. She wished she had changed her shoes. She had never thought about shoes before except to wish she never had to wear any.

"We'll have to describe our dog," Tommy said. "The police will want to know what he looks like."

"Well, I remember him perfectly," said Jo Ann. "I remember him just as well as if I'd seen him this very day. He's a cunning little puppy you could hold in your two hands, and all fuzzy and brownish with a white face."

"There was a dark spot on him somewhere," said Tommy.

"Yes, down near the tail end of him," agreed Jo Ann. "A blackish brown spot about as big as a dollar. Listen -- what's that?"

The noise they heard was the complaining whine of what was evidently a puppy that resented being where it was. Between whines it uttered short little barks that begged anyone hearing it to come to it.

"Tommy!" Jo Ann exclaimed.

"That sounds like our dog! Don't you think it does?"

"Yes, it does," said Tommy, for once agreeing with her.

They had now crossed the vacant lots and were on the edge of the more closely settled part of town. They were shut off from the whining puppy by a tall board fence. Along the top of the fence ran two strands of barbwire. Jo Ann searched the fence until she found a small knothole. She put her eye to this and looked in.

"Tommy," she said, "take a look in there. That's our dog. I know it's our dog."

Tommy looked through the knothole.

"Yes, sir!" he exclaimed. "If that's not our dog I don't know a dog when I see one."

"Call to him," said Jo Ann, "and see if he knows his name."

"Here Sport! Here Sport! Come here, old fellow." Tommy called pleadingly with his mouth to the knothole.

"Calling him like that's no good," said Jo Ann. "He wouldn't know that name. Mother probably called him Rags all summer. Call him Rags."

"It wouldn't be any good anyway," Tommy said. "I can't call him through this knothole and then get my eye to it quick enough to see whether he knows his name or not. Can we find another hole, so I can call while you look?"

"It would be better for you to look while I call," said Jo Ann, "because it was my mother who called him Rags if anybody did, and my voice would be more like my mother's." But neither one could find another knothole.

"We'd better go around in front," suggested Tommy, "and ask the people where they got the dog."

"Yes," Jo Ann agreed. "And you watch to see if they look guilty, Tommy. They probably will if they stole him. We'll say 'We think that's our dog; where did you get him and how long have you had him?' and see what they say. We can try, anyhow."

There were houses on either side of the one that had the wall-like fence and Tommy and Jo Ann had to walk around these to reach the front. The yard had an ordinary picket fence with a gate but the gate stood partly open. The house was a smallish house and even at the first glance no one seemed at home. All the shutters were closed. Jo Ann went straight to the front door and looked for a bell but there was none and she rapped on the door. She rapped several times and no one came to the door, so she led the way to the back door. Her rapping there brought no more signs of life.

"There's no one at home, I guess," she said.

"There's somebody next door," said Tommy and, sure enough, a woman was looking through a window at them. She was in her kitchen and when she saw Tommy and Jo Ann looking toward her she opened the window. She said something, but it was in a language Tommy and Jo Ann could not understand. Evidently she was telling them something and asking them a question.

"We think the dog in that pen or coop, or whatever it is, is our dog," Jo Ann said. "Our dog got lost yesterday, or someone stole it. Do you know when these people got that dog?"

"No spik Inglis," said the woman with an air of finality.

"Well, anyway," said Jo Ann, "we're going to look in that coop and see if it's our dog. Will that be all right?"

The woman raised her hands and shrugged her shoulders.

"No spik Inglis," she said again, and with that she closed her window.

"She wasn't very talkative, was she?" said Jo Ann. "But she didn't act as if anyone would care. We'd better look, Tommy; it would be silly to ask the police to find our dog for us if this is our dog right here."

"We could make sure," said Tommy, "and if it is our dog we can tell the police."

But the fence that enclosed the puppy was as tall and as tight on this side as on the other side, Jo Ann found. The boards were smooth and joined tightly together and had the same strands of barbwire at the top. There was not even a knothole. Instead of a gate the fence had what was practically a door, close-fitting and fastened with a staunch padlock. The whole place had a very mysterious air about it.

Jo Ann looked about her. "It's a funny kind of place," she said. Whatever do you suppose anybody would build this sort of place for?"

"He might be going to raise some kind of animals," said Tommy. "It might be foxes. They raise foxes for fur, and I've seen fox farms where they charge admission to go in and see the foxes. The barbwire would keep people from getting in to steal the foxes and the tight fence would keep them from seeing the foxes without paying."

"Yes," said Jo Ann. "Foxes or," and she lowered her voice, "dogs. Stolen dogs, Tommy. If he started to be a dog-raiser and meant to steal the dogs to begin with, he would build just such a pen, wouldn't he? Tommy, I wouldn't be surprised if this was where all those stolen dogs were hidden when they were stolen! All tight and secret so no one could see in, don't you see? I just know that's our pup now! We've got to get him! Let's think up a way."

"I don't see how we're going to, Jo Ann," Tommy said, surveying the tall fence and the barbwire on its top. "You can't climb that fence. Nobody could. It's too high in the first place, and look at that wire."

Jo Ann looked at the fence and then upward at a tree that stood nearby. The limbs of the tree had been cut off well up the tree's trunk but one of the lower limbs that remained extended out over the mysterious fence and partly across the enclosure that held the puppy. The limb was too high to drop from. It was a drop that would have daunted anyone, even such a tomboy as Jo Ann, but Jo Ann was an old hand when it came to tree climbing. She was as thoroughly at home in a tree as any squirrel. Tommy followed her eyes.

"That's no good," he said. "You wouldn't dare drop from that branch, and if you did you couldn't get out of the pen again."

"Couldn't I? Watch me, Tommy!" Jo Ann replied.

She sat down and took off her sneakers and her stockings, rolling them into a ball.

"Hold these," she said, handing them to Tommy. "I suppose you could do this just as well as I can, you're so wonderful at doing things, but maybe you'd like to see what a girl can do. And I wouldn't want you to spoil your nice clothes, trying to do this."

Tommy said nothing, but took the shoes and stockings Jo Ann was silently holding out to him. The fact remained that he did not see how Jo Ann could get into the pen and out again even if she did climb the tree. But Jo Ann walked to the tree. She gave a little jump and grasped the trunk as high as she could, clinging with her arms and pressing with the inner sides of her calves, and thus she went slowly up the tree until she could reach a branch.

With her hand on the branch, the rest was easy. From the branch a rope swing had been hung. Now the rope was drawn up and looped over the branch, but Jo Ann unlooped it, edged out along the branch, drawing the swing rope with her, and when she was over the pen she made a hitch around the branch with the rope. Down it she went, hand over hand.

When her feet were firmly on the ground inside the pen, Jo Ann cautiously loosened her hold on the rope.

"I'm in!" she called to Tommy, and gave her attention to the puppy.

"Rags! Here, Rags!" Jo Ann called, but the eagerness of the pup to come to her proved nothing. He had come as far as the rope would let him when Jo Ann dropped into the pen.

"Is he our dog?" Tommy called.

"I'm sure he is," Jo Ann answered. "He has a white nose and a blackish-brown spot near his tail. He's just crazy to see me. Tommy, and --"

"Keep quiet!" said Tommy suddenly. "Policeman coming. Keep still, Jo Ann."

"And who may you be, young feller?" said a louder voice. "What you doing here? You live here? Speak up, now!"

"No, sir," said Tommy. "I'm just here."

"What's that you've got in your hand there?" asked the policeman.

"This?" said Tommy. "Why, it's -- it's just my shoes and stockings."

"Let me see," said the policeman. "So, ho! Your shoes and stockings, are they? Ladies' sneakers. Where did you get these?"

"Well, a -- a lady told me to keep them for her," said poor Tommy.

"And did she now!" said the policeman. "We'll see about that later on. What are you doing here? I want a straight answer young feller. Are you a dog stealer?"

"No, sir," said Tommy.

"No? Well, you don't look like a thief, and that's the truth, but why are you here?"

"I was going by and I heard a dog," said Tommy. "So I thought, 'Maybe that's my dog. I'll go in and see if it is.' So I came in. But the gate of the pen was locked. So I was standing here."

"All alone?"

"Yes, sir. I don't see anybody else, do you ?"

"And what's your name, you that was standing here all alone with a lady's shoes and stockings and not seeing anybody else?"

"Thomas Bassick," said Tommy.

"Well! Well! And if I was to take you off to jail for trespassing on property that don't belong to you, you'd still say you was here all alone?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you'd say nothing about the young lady I seen go down yon rope just now?"

"I don't know what you're talking about," said Tommy bravely, afraid to look around.

"You do, too, Tommy Bassick!" cried Jo Ann from inside the pen, "and I'm much obliged to you, but if you're going to be arrested for trying to get your half of our dog, I'm going with you!" and with that Jo Ann began climbing up the rope.

"Go easy there or you'll be breaking your neck, miss," the policeman said.

"I've never fallen out of a tree yet," Jo Ann said. "If anybody is going to be arrested you can arrest me, too, for I own half the dog and I'm as much here as Tommy."

"More so!" laughed the policeman. "So you're the young lady of the shoes and stockings? Sure, I know you by reputation, do I not? Jo Ann, ain't you? 'Twas my own boy, Terry, was one of your tribe of Indians when you lived over the other side of town."

"Terry Casey? How is he?" Jo Ann asked.

"Fine and well," said the policeman. "And now see you here, the both of you -- never do this again. You can see what trouble you might have got in. For this is the house where a dog stealer hung out and I took him to the jail but two hours ago."

"Did you really and truly, Mr. Casey?" asked Jo Ann.

"I did. And put on your hosiery now, for I have the key to this padlock and if 'tis your pup whining you'll soon have him."

"You I don't know, sir," he said to Tommy, "but I compliment you for a gallant lad, trying to take all the trouble on yourself and protect the young lady. Only the next time, climb the tree for her."

"He had on his good suit," said Jo Ann.

"Sir Walter Raleigh had on grand clothes when he slammed down his cloak in the mud for a lady to walk on," said Policeman Casey.

"Yes, sir," said Tommy.

"And here, now, is your pup," said the officer, swinging open the door.

Tommy and Jo Ann took him.

"We're ever so much obliged to you," Jo Ann said, as they started toward home.

"I'll tell you what," said Tommy when they were almost there. "Let's have a combination name for our dog. 'Rags-Sport' is too hard to say, and 'Sport-Rags' sounds like some kind of clothes to play tennis or golf in. Let's call him part of each and make it 'Spags'."

Jo Ann considered this a minute or so.

"Yes," she said. "I'm willing. And Tommy -- it was swell of you to try to keep Mr. Casey from arresting me."

"Oh! Cut it out!" said Tommy. "Forget it. Say, Jo Ann," he continued, "don't ever tell anybody. They'd guy me awfully."

"All right," Jo Ann agreed. "I won't tell," and thus in greater friendliness than ever before they reached home. They bore straight for the double-doored kennel and Jo Ann's mother saw them and came hurrying out.

"My gracious!" she exclaimed. "What do you want another dog for?"

"Another dog?" Jo Ann asked, amazed.

"Your dog came home two hours ago, dragging his rope behind him," said Jo Ann's mother, and sure enough, there he was. He was not in the least like the pup Jo Ann and Tommy had brought home. They had forgotten how fast a pup grows.

"Oh, crickets!" exclaimed Jo Ann. "We almost did steal a dog, Tommy! I wonder whose dog this is?"