from Rotarian

Who's Your Friend?

by Ellis Parker Butler

What I mean to say is something like this -- we have a white dog at our house, one of the fluffy sort of fox terrier dogs with white hair and a palate that seems to react more joyously to a juicy chunk of mail carrier's calf than to a kiln dried dog biscuit; and out here in Flushing the mail carriers are simply sick and tired of having pieces bitten out of their calves. That, I suppose, is because most of them are married and hate to go home to a poor tired wife at the end of the day with the calf of one leg showing a large concave indentation or gulf. Nothing annoys a mail carrier's tired wife more than to have her husband come home about six o'clock in the evening with a large chunk of calf in one hand and to have him say, "Darling, Butler's dog has bitten another piece out of my calf; I wonder if you would mind sewing it on again?" Very often this happens when the mail carrier's wife is trying to hurry dinner on the table so that they may go to the movies, and it annoys her considerably.

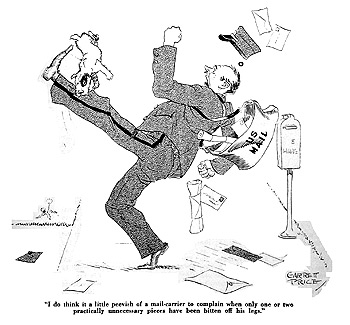

There are a couple of mail carriers in our town whose wives get so provoked when they are asked to do this same job over and over that they have quit bothering their wives about it, and when a dog removes a chunk of calf from them they return home quietly and get the liquid glue or the white library paste and glue the chunk back where it came from, but this is not satisfactory, either, because it is so damp out here on Long Island and the glue loosens up, and a mail carrier hates to go about town with pieces of his calf falling off here and there. So the mail carriers have formed Mail Carriers' Union No. 1, and the first bylaw of the union is "No mail will be delivered to houses that have dogs that bite us on the legs." Personally, I think this is a perfectly just rule. I do think it is a little peevish of a mail carrier to complain when only one or two practically unnecessary pieces have been bitten off his legs, but when a mail carrier's underpinnings begin to get whittled down so that there is practically no nourishment left on them I think he is well within his rights when he calls attention to Rule 1, if he does it pleasantly and not in a mean or spiteful tone of voice.

For these reasons we try to keep our dog in the house, especially during the first thirty or thirty-one days of the month, which are the days on which our trades-people send us bills and duns. If we let the dog out and the mail carrier passes us by we might miss a communication from our grocer or coal man and never know that he was still willing to accept payment. And I remember one particularly annoying instance when our postman passed us by and a communication, neatly printed in imitation typewriting, from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Mexican Lizards -- and calling attention to the fact that a contribution of $5 would permit me to be a Contributing Member, while a gift of $1,000 would make me a Life Member -- did not reach me until two days later. I still am annoyed when I think of this. As a businessman I hate such delays in the delivery of my important mail.

You can see, I think, that when we decided that our dog should be no longer a calf-biter or, to use the technical term, a Mud-Hound or Outdoor Nuisance, it became necessary to launder him more or less frequently. Roughly speaking it is not classy to sport a white Rug-Hound or Indoor Nuisance that is the color of bituminous coal. It annoys a caller if she pats the family pet once or twice and then has to spend an hour or two with a can of lye and a scrubbing brush getting her hand white again. For this reason our dog is laundered from time to time and a small pinch of indigo in the second, or rinsing, water makes him a beautiful creature with silvery white hair and fit to associate with the best Flushing society. Now and then, however, General Andrew Pickens -- that being our dog's name -- makes a sudden dash when a door is opened and after two or three hours in the open returns looking as if soap had never been invented and water was a fluid used only to quench thirst.

There is no doubt that when General Andrew Pickens is out he has a good time. He is like the man who cries, "Now for the woods! Now for old clothes and no more shaving or bathing or any of that nonsense until vacation is ended!" When our dog makes his escape he leaves behind him, as one might say, the creased trouser and the clean white collar and the nail file. He does not take his toothbrush with him, and the only shirt he takes is the one on his back. And when he returns he is a thoroughly non-parlor-looking dog. When he scratches on the door and is let in he shows that he knows he is not a presentable dog. He comes in with a shamed look in his eyes and his tail down, and he steals quietly to the kitchen and effaces himself there. He doesn't go into the living room because he knows he would be out of place there; he is in no shape to mix with polite society. He knows it. He goes where he can curl up under a sink and associate with the dustpan and the lower end of the ironing board, and other such lowly society.

Now, I claim that if a dog prefers the society of a dustpan and the lower end of an ironing board to that of the classy human beings who assemble in the front part of the house, he has a right to prefer it and to congregate with it under the sink where it is, but our dog doesn't prefer it. What he likes best is to get right in the middle of the living room, in the very bosom of good society, and repose there with his nose on his paws, listening to the bans mots and hoping for bonbons. General Andrew Pickens is never so unhappy as when he knows he looks like a secondhand floor mop and feels that the lower end of the ironing board and the battered tin dustpan are about his size and shape and grade. When that dog of ours sneaks out to the sink he is not choosing the companionship he desires but the companionship he thinks his soiled garb and general disreputable appearance dooms him to.

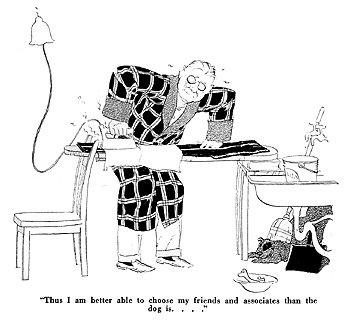

I think I have, personally, an inside edge on the dog, because -- if I want to -- I can usually keep at least one clean collar in reserve and when millionaires or other royalty invite me out to tea I can wrestle with the ironing board and the electric iron and put a crease in my society pants that is almost equal to the professional product. Thus I am better able to choose my friends and associates than the dog is, and if the spirit moves me I can press my trousers and put on the clean collar and without hesitation or qualm toddle over to Mrs. Spinks' house and be bored in a style equal to that of the very best people in her set. Or I can borrow a pair of mauve spats and fearlessly accept an invitation to the Biddlebury's tea. I can even tie a piece of black ribbon to my eye glasses and hang my old wooden umbrella handle over my arm and partake of the afternoon hospitality of the Vanderhootens as unabashedly as anyone, and feel as much at home as the best of them. My dog, on the other hand, has not yet grasped the ability to go down cellar, turn on the hot and cold water, manipulate the soap and the wash-blue, and give himself a beauty bath. This restricts his choice of companionship.

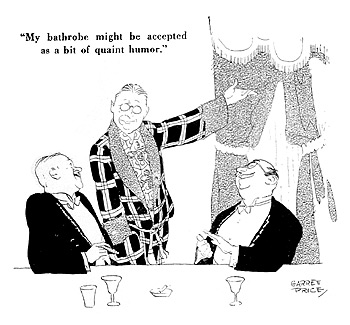

Roughly speaking, I think every man and woman should strive to keep on hand the right sort of clothes to permit him or her to go forth without hesitation and enjoy whatever sort of companionship he or she desires. A man, for example, who longs to attend formal dinners where evening dress is imperative should strive to maintain a dress suit, because if his wardrobe is such that, when he takes off his business suit, he has nothing to put on but a bathrobe, he usually feels an innate reluctance to go to the banquet. My own feeling is that if I were confined to those two sorts of garments I would make a bigger hit at a banquet if I wore the bathrobe, but that is only because I have a reputation as a humorist and my bathrobe might be accepted as a bit of quaint humor. It is one I bought in Paris in 1908. Ordinary men, however, such as bill clerks, secretaries of state, presidents of crematories, bankers, and milkmen -- and all women except authors of social-decay novels and free verse -- should try to have on hand a style of evening dress more formal than the huckaback bathrobe if they wish to attend evening functions and feel really comfortable.

This same rule applies to garments for all occasions. Any great expenditure for clothes is unnecessary, every human being feels some reluctance in going where he knows he will look out of place. The right clothes, it has been said, give a woman a feeling of content only equaled and not surpassed by the sure knowledge that her soul is saved, and they give a man a feeling of preparedness that is first cousin to courage. No man can thoroughly enjoy himself or be at his best when he is thinking that he is the only man in the crowd who looks like a dishrag at a convention of pocket-handkerchiefs. This is not confined to the matter of full dress, either. It applies to all dress. In many towns and small cities the large white shirt-front and the vest with its chest protecting portion bit out are not considered human attire but an evidence of mental weakness, and they are worn only by church-choir tenors and visiting lyceum lecturers. In these places the proper banquet costume and the wear of the best society on all occasions is the business suit, either with or without the button of the Admirable and Eminent Order of the Sons of Success -- or some other lodge -- in the lapel. But in these places you find the same bitter regrets stinging some bosoms when the Chamber of Commerce banquet comes around, or when Mr. and Mrs. Ooplah Riches requests the presence of your company, 8:30 P. M. -- dancing. Then John P. Smith takes a look at his business suit and observes that it looks like something the cat brought in and that the dog has been sleeping on since April 3d last, and he sees that the knees and elbows look as if they had been shaved and then sand-papered, and that there are eight spots of red ink on the left leg of the trousers, and he sends his regrets and bites a piece out of the top of the bureau, in his anger and remorse. Bill C. Jones, on the other hand, gives his natty business suit a lookover, scrubs the soup stain from the lapel with the wet face rag, and trots right along and has a good time and is happy. He dances twice with Mrs. Morpheus K. Duttz and she invites him to join the Tuesday Evening Club, and ten days later she drops into his place and buys from him the automobile she had intended to buy in Chicago.

I think there is no question that a man is more comfortable in any group if he is dressed, sartorially and mentally, more or less as that group is dressed. He feels more at home in the group. He feels more as if he belonged there. Even a lion if he wants to associate with jack-asses, will find them more friendly and willing to accept him as an equal and companion if he wears an ass's skin when he goes to their party. That clothes do not make the man has been reiterated innumerable times, and it is a truth, but it is equally true that a great many men and women draw back from companionships and friendships they would enjoy and that would profit them, and they do so because the clothes they happen to have would make them feel out of place and uncomfortable.

The same is true in a lesser way of houses and furniture and such things. If our furniture is old and disreputable looking, or our furnace leaves the house as cold as a barn, these things sometimes prevent us from eager affiliation with a group we will have to invite to our home. Gradually we give up some friends we would like to keep and confine our friendships to those whose homes are no better than ours. I don't believe that is very good; the friends we sift down to may be the best people in the world, too. It is a pity to give them up. And from a purely worldly point of view it is not good at all to get so completely out of the living room or to begin to class ourselves, although unconsciously, with the dustpan and the lower end of that ironing board under the sink. Before long we begin to think we belong there, and that that is the sort of folks we are, and that we never were any better than a dustpan and never can be any better. We get to thinking of ourselves as under-the-sink people, and there we stay. We begin to be satisfied to be cheap and poor and untidy and hand-to-mouth, and that is not so good for us.

A boy may have a dog that is an absolute mutt, a regular yaller dorg out of the gutter, and that dog may be the best friend and most faithful companion that boy has in the world. It may be the kindest and wisest and most affectionate dog in seven counties, and I think that boy would be a mighty mean boy if he tied a can to that dog's tail and chased it off the lot and got rid of it, because a true friend is a true friend whether he comes from under the sink or out of the parlor; but there is no denying that if he tried to get that dog into a real dog show he would not have a chance in the world -- that is, provided, of course, he was interested in getting him into a dog show and he thought dog shows were important. That dog is not in the dog show class. And it is also true that a dog of the dog show class can also be the best friend and most faithful companion and the kindest and wisest and most affectionate dog in seven counties. Well-to-do and intelligent and well-educated people can be just as good friends as slovenly, impoverished, and ignorant people. They often are. You don't have to crawl under the sink to find genuine friends. They are scattered all over the house.

I was reading the other day a book on the wonderful Mayan civilization that existed in Yucatan and in the days before America was discovered by Columbus and in the book was given a picture of a copper bell, similar to our sleigh bells, and the author said this bell was the most widespread object of metal found in all those regions. He says that Cogolludo, who wrote back in 1688, says copper bells were used among the Mayans as a medium of exchange -- as money, in fact. Copper and gold bells were found in the ruins of the four great ancient civilizations of North and Central America -- Aztec, Mayan, Zapotecan and Tarascan -- and in one place a very large number were found in a cache -- some old fellow's bank account, I suppose. Other similar caches of similar bells have been found.

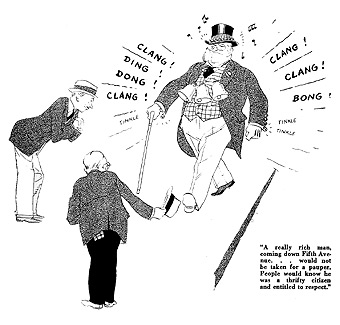

I admit that I rather like this idea of a legal tender currency that can make a few cheerful remarks as you tote it around. It would show whether a man was prosperous or not. If you met a man who did not jingle at all you would spot him instantly as the village ne'er-do-well, but if you met a man who jingled like a two-horse sleigh you would know he was a solid, substantial citizen, worth all of $48.60 in good cash money. And when you heard a noise coming down the street that sounded like a load of steel bars and the Christmas chimes and the Swiss Bell Ringers all combined in one, you would be dead sure it was someone worth edging up to -- Mr. Huitzilihuitl of the Tenochtitlan National Bank, or Billy Axayacatl of the Tezcatlipoca Trust Company, or perhaps Mrs. Coatlicue, whose husband owned the Popocatapetl Sulphur Mine.

When Mr. Huitzilihuitl came strolling down Xocoyotzin Avenue making a noise like a million dollars, you could depend on seeing plenty of people crowding around him and kow-towing to him, but you could spot the sycophants instantly -- the crowders-in who wanted to make something out of him, borrow a couple of bells for a few weeks or get him to buy a few shares in the United Aztec Human Sacrifice Supply Company -- because they would hardly jingle at all, even when they were joggled. And you could tell his friends with equal ease by the coppery jangle they gave forth as they walked. But Mr. Huitzilihuitl would have a warm handshake for some others; he would have a handshake, for instance for this young fellow with eight copper bells strung around his neck and a genuine eighteen-carat gold bell hanging from the end of his nose. His words might be "Howdy, Tizoc; how's the boy? Come up to the house tonight and we'll have a little game of Mah Jongg," but his thought would be "There's a boy! Only a five-beller last month and now he's a nine-beller, and one of them gold. There's a lad who knows how to get along on his own hook; he doesn't want to borrow money from me; he likes me because he likes me. That boy is going to make a big jingle in the world before he is through. Fine fellow!"

This idea of noisy money is not altogether a bad one. We have in the U. S. A. one of the meanest pieces of paper money that was ever printed -- our two-dollar bill. It is the sneakingest piece of money I ever saw, and it will gumshoe in among a lot of one-dollar bills and sit there without uttering a peep, and before you know it you have grasped it and paid it out instead of a dollar bill. You start out with eight dollars in your pocket -- six ones and one of these pussy-footed two's and buy something for one dollar, and when you reach home you discover you have only six dollars left. I think our Government would do well if it retired those deaf-and-dumb two-dollar bills and minted a handsome twenty-dollar gold piece in the form of a sleigh bell, with a small ring at the top so you could wear it around your neck or on your watch chain. If I was running the mint I would coin a lot of different varieties of this sleigh bell money -- A-Flat and B-Sharp and the whole scale -- so that a man would want to get a full set to wear around his neck to give off a sweetly harmonious tune when he walked. This would encourage us to save money.

It might be necessary to coin something other than sleigh bells. I would not, for example, care to be J. P. Morgan and go on an ocean voyage with all my money strung on me, because in case of wreck it would sink me too suddenly. I think this difficulty could be overcome by coining $1,000 sheep bells and, let us say, $1,000,000 fire engine gongs. A really rich man, coming down Fifth Avenue with two- or three-dozen solid-gold fire gongs sewed to his chest and all gonging at once like a three-alarm fire would not be taken for a pauper. People would know he was a thrifty citizen and entitled to respect.

In a way, I suppose, diamonds and houses and things of that sort serve now in place of self-advertising money of the sleigh bell variety, but a man usually makes his wife carry the diamonds around, and it is not always convenient for a fellow to hunt up a man's wife to see whether that man is worthy of financial respect or not. She may be in Europe, or at Palm Beach, or she may be camping in Canada and have the diamonds locked up in a safe deposit box.

I think it is rather a shame that it has come to be the style to consider money something mean and sordid. I suspect that this is because money can earn interest and a man can own money outright. This puts money in the slave class, because a slave is owned and works for its owner, too, and as slavery is sordid we have come to think of money as being sordid. This would not be the case if money was more showy and interesting and made in the form of platinum sleigh bells set with diamonds. A person could then get some real enjoyment out of his money without setting it to work or spending it for one thing or another.

Personally, I always like to think of money as wheat -- that a dollar bill is a bushel of wheat, let us say. Then, if I have saved ten dollars I have ten bushels of wheat in a pile, and I can trade that wheat for a pair of shoes, or feed my family with it. If you look forward to next year and can't be absolutely sure what your harvest is going to be, it is a satisfaction to know you have ten bushels of wheat on hand, no matter what happens, that will keep your family and yourself alive awhile while you are pecking around for more. When you think of money as wheat you are less apt to fill your pockets with it and go forth and throw it away. If a man starts for home with a dollar in his pocket and a good beefsteak under his arm he may stop and gamble away the dollar in a nickel-in-the-slot machine, but he hangs onto the beefsteak.

A dollar in the bank is good wheat in the bin or good beefsteak in the refrigerator and when you throw away a dollar you are throwing away good food that may keep you from being hungry some day.

And that brings me to what I want to say about friends. I think a man, particularly a young man but also older men, ought to try to choose friends among the most prosperous people he can find, provided they can meet his intellectual requirements, and they usually can do that. To be ready to take advantage of opportunities to associate with prosperous people a man should try to have the mental and sartorial clothing that will prevent him from feeling out of place in their company.

That a man who finds his greatest enjoyment in intellectual companionship should try to associate with men of superior intelligence is too evident to need explanation. Everyone knows that. The better the brains with which you come in contact the better your own brain will be. But it is equally true that the more prosperous the people with whom you associate the more prosperous you will be. And this does not mean sycophancy or hanging on. Not at all.

Imagine four villages in four parts of the country. One of these villages is a shiftless village! Nobody does much work and nobody ever stores up much wheat. The wheat bins are always empty; everybody is sort of happy-go-lucky and everybody goes hungry at times. It has become the custom there. A young man comes to this village and makes it his home. Unless he is a wonder, it is not long before he is just as shiftless as the rest of the inhabitants. It is a "poor" community, and nobody stores up wheat, and neither does he. If he stays there the rest of his life the chances are he will be as shiftless as the rest, and go hungry as often. There are no wheat bins full of wheat to inspire him to have a full bin of his own.

But something takes him to the next village on the list. Here it has become the habit to store enough wheat to last half through the winter. Almost instinctively the young fellow will follow the custom and try to store enough wheat to last half the winter. He will go hungry only half the winter.

But he goes on to the next village. Here the custom is to store enough wheat to last the entire winter through, and he falls into the same habit. He is never hungry; there is always wheat in the bin. Almost in spite of what may be his natural inclination he finds himself following the common custom of the community and doing as others do. If his bin is empty by January he feels cheap. He feels that he does not belong in the full-bin class and he drops back to the half-bin village.

But it may be that he goes on to the last of the four villages, or is born there. Here it is the custom to have plenty of wheat stored not only for one winter, but for several winters. The barns are all well built and neatly painted, the wheat bins stand in rows, each filled to the top.

What I say is that the young fellow will feel the influence of those comfortable well-filled bins in spite of himself. He will be in a plenty-wheat atmosphere. Full bins and plenty of them are taken as a matter of course. A man is expected to have wheat and lots of it. Not to have wheat is considered -- accidents barred -- a sign of carelessness or poor judgment or weakness of mentality or something.

Association with poverty tends to poverty; association with wealth tends toward wealth -- it incites ambition. I know a man who for many years was doing wonderful work in an institution in the less prosperous section of one of our big cities, practically in the slums. I met him not long ago and he said he had resigned and was doing something else because he had begun to feel the effect of all that poverty on himself. He was beginning to feel poor and broken in spirit because he met so very many who were poor and broken in spirit. He felt he must, for a while, get into an atmosphere of prosperity or he would be done for. And he was right. If you let your dog hide under the sink with the lower end of the ironing board and the tin dustpan too long he will soon come to believe that that is where he belongs. He will be happy nowhere else. You may wash him and blue him and iron him and he may sneak into the parlor when no one is there, but when Mrs. Biddlebury comes to call he will put his tail between his legs and steal back to the underneathness of that sink.

No man or woman should be a sycophant or a hanger-on -- heaven forbid! But why expect to be successful if you choose your friends among the unsuccessful? It is all well enough to say, "When in Rome do as the Romans do," but to do as the Romans do you must first go to Rome. It is also all very well to say, "Try for success," but you cannot breathe the air of success if all your friends and associates are failures. You don't get the mountaintop air in the lowland swamp -- you get malaria.

And when you come right down to statistics you'll find that the people in the swamp spend just about as much money for quinine as those on the heights spend for caviar and quail on toast. It is largely a matter of habit; if your friends are the successful you ' will breathe the air of success; if your friends are the failures you will breathe the air of failure. And the air a man breathes gets into his blood.