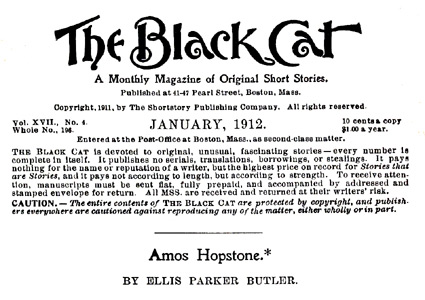

from Black Cat

Amos Hopstone

by Ellis Parker Butler

Through my profession of genealogist I have met many strange persons, but Amos Hopstone was the first to come to me to satisfy the cravings of an unsatisfied vengeance. The moment he mentioned his name I turned to the H drawer in my card index. "Hopstone, Amos," I read there. "The last of the Hopstones. The entire line, except Amos, killed in the famous Gibsmith-Hopstone feud," etc.

"Well, Mr. Hopstone," I said, turning to him, "what can I do for you?"

I cannot give an adequate idea of the horrid appearance of Amos Hopstone. This man who, with his own hand, had killed twenty-seven Gibsmiths bore all the marks of an unutterable villain. His coat hitched up in the back where it caught on the handles of two immense pistols, and a strange protuberance on his leg was caused by the handle of a bowie knife carried in his boot. His long mustaches drooped on either side of his mouth, and his jet black hair fell loosely from under an old slouch hat. His eyes glittered savagely.

"Maybe you can do something for me, and maybe you can't," he said, harshly. "I'm Amos Hopstone, and I'm the man that killed twenty-seven Gibsmiths in twenty-six days. That's one a day and one over, but it ain't the record. Old Sime Gibsmith killed twenty-nine Hopstones in twenty-six days. That's the record, but I'd have beat it if I hadn't run out of Gibsmiths. I thought, seeing how as keeping track of folks was your business, maybe you could look me up another batch of Gibsmiths."

"No," I said. "There are no more Gibsmiths. You killed them all."

"I reckoned so," said Amos Hopstone, with a smile that was half regret and half pride. "And that ain't all. I've used up all the Jimpfers -- they was cousins to the Gibsmiths. I killed sixteen Jimpfers in twenty-two days. You can file the Jimpfers away with the dodo birds -- they're extinct. And I've used up all the Ranbecks -- they was second cousins to the Gibsmiths. And I've used up all the Newfiggs, and all the Praddles, and all the Hilums, and all the Nypers, and all the Doublegarths. I've stripped all them branches. Not a one left. What I want you to do is to look up some more branches. If I could get on the trail of a real hearty branch -- one with thirty people in it, say -- I'd have a try at old Sime Gibsmith's record. I'd try to kill the whole thirty in twenty-six days. Gibsmiths and relatives of Gibsmiths is poison to me!"

I did not much like the task proposed by Amos Hopstone. I disliked the idea of furnishing genealogical records merely that old Sime Gibsmith's killing record might be beaten. I told Amos Hopstone as much.

"All right, pardner," he said, "just forget that part of it. But you look like a man who would do thorough work when he took to it as a business."

"Mr. Hopstone," I said, "that is so. You are a man of discernment."

"That's right!" he declared. "I practiced discerning a long time, and I got so I could discern a Gibsmith or a Praddle as far as I could see one, and I can shoot as far as I can discern. 'Discerning an' Thorough,' -- that's my motto. If I've killed off all the Gibsmiths' and all their relatives, I'm satisfied, but if I haven't I don't call it a thorough job. I want to be thorough."

He drew from his coat pocket a roll of paper and spread it on my desk.

"Here," he said, "is a list of all the Gibsmiths and all their branches as far back as the Revolutionary War, when Pete Gibsmith moved to Kaintucky. That's as far back as I can go alone. All I want you to do is to hunt up where Pete Gibsmith come from, and see if he had any sisters, and if any of them married into other families, and let me know, or if he had any brothers that --"

I stared at the name of Peter Gibsmith. After seeing that name, and the date of his birth, I would not have allowed Amos Hopstone to go to any other genealogist for anything in the world.

"Mr. Hopstone," I said, "I will undertake the research, but my usual charge for work of this character --"

"Now, Mr. Wilmot," he said, "that's one thing I wanted to talk to you about. I'm out of money. And up here in New York, where nobody knows me, it is hard to get a job. I thought maybe you could recommend me to a good job. I'd turn over to you every cent of my wages every Saturday night."

For reasons which you will soon understand I did not wish Amos Hopstone to get out of my sight, and I put my hand on his arm.

"Mr. Hopstone," I said, "I have the very place for you! I live in a boardinghouse, but only last night my neighbor, Edgar Smith, asked me if I knew of a strong, attractive gentleman to do the work on his place. You do not object to the -- ah -- to the music of a cornet?"

"I can stand it," said Amos Hopstone.

"Because," I said, modestly, "I often call at Mr. Edgar Smith's home and play the cornet there."

It was thus I placed Amos Hopstone in the home of Edgar Smith. My name is Samuel Wilmot, and I became acquainted with Edgar Smith through my professional duties. He came to me, in short, to have his genealogical tree dug up, and the acquaintance ripened into friendship rapidly, particularly as there was a most charming young lady in Mr. Smith's family -- his sister, Kate Smith.

Mr. Smith was delighted to secure the services of Amos Hopstone. There was a great deal of work to be done about his place, and he had long wished to keep a horse, but his income was such that be could not afford to keep both a man and a maid servant, and he found it would be necessary to have either a maid who would also attend to the horse, or a man who would do the housework. Amos Hopstone readily agreed to this. Vengeance, as inculcated by the feudists of Kentucky, is an overwhelming passion and drowns all lighter considerations.

Amos Hopstone went about his new duties cheerfully. Whether he was in the stable currying the horse, or in the basement washing the clothes, or in the yard cutting the grass, or in the dining room waiting on the table, he maintained a bright, optimistic demeanor, singing cheerfully or whistling. Mr. Smith sometimes wished Amos would not whistle while waiting on the table, but, after all, it is better to have a cheerful person about the house than a sulky one. He also tried to have Amos shave off his mustaches, but the most he could persuade him to do was to curl them. When this was done and Amos donned his white apron with the nicely ruffled shoulder pieces he made a neat waiting maid. Mr. Smith also tried to make Amos give up his pistols, because he looked strange wheeling the baby carriage with two great pistol-butts protruding from his pockets, but in this he was unsuccessful.

From time to time Amos asked me to hurry up my researches a little. He said the job I had secured for him was a good job, but it annoyed him, while currying the horse, to have to strip off his overalls, rush to the house, curl his mustache, and put on his white apron to answer the doorbell, only to find it had been rung by a peddler selling patent self-heating hair-curlers. I told him I was proceeding as rapidly as possible, and thus two years passed. At the end of every week Amos Hopstone handed me his wages as he had agreed. His afternoons off he spent calmly, cleaning his pistols and sharpening his bowie knife.

As I have said, the Smith's home was brightened by the presence of a charming girl. She was full of life and vivacity, and an excellent performer on the mandolin, and while all the young men of the neighborhood admired her, she seemed to prefer me to any of them, because I am a cornetist in an amateur way.

We often spent an evening together playing duets. It was, therefore, no surprise to Edgar Smith to hear that I had proposed to Kate, but it was a great shock to me when Edgar Smith absolutely forbade the marriage. And yet his reason was both simple and logical. While his decision almost broke my heart I could not blame him.

Mr. Smith's mother lived on a farm in New Hampshire, and my Grandfather Wilmot lived on the adjoining farm. For many years they were such good neighbors that when the pump on my Grandfather's farm broke down he did not take the trouble to repair it. Every evening he led his cow across Grandma Smith's dooryard to a small brook that ran through her farm, and there his cow took a cool, refreshing drink of water before retiring to rest. This brook water was slightly mineral, containing a little iron and a little sulphur, which gave it a peculiar taste, and the cow became so fond of this that she would drink no other water. Her calf inherited the taste, and so did that calf's calf. Thus it became absolutely necessary for Grandfather Wilmot and his cow to make the trip to the brook every evening, and in hot weather when a cow is apt to be especially thirsty, every morning too, but Grandma Smith did not care, for a brook is not apt to be emptied by the efforts of one cow.

But all this neighborly good feeling ended suddenly. The original cow died, and her calf grew to cowhood and died, and thus cow succeeded cow for many years, but at last a calf was born that had an ungovernable temper, and this calf took a dislike to a red dress with white spots that Grandma Smith wore. Whenever Grandma Smith was in her garden this calf -- now grown to be a cow -- would break away from the hands of Grandpa Wilmot -- who was growing feeble -- and would chase Grandma Smith angrily. Several times she narrowly escaped with her life, and then she forbade Grandpa Wilmot the right of way to the brook, and thus it happened that at the very time I was pouring out my heart to Kate Smith on the cornet, and she was tremulously replying on the mandolin, Grandpa Wilmot and Grandma Smith were preparing to go to law about the cow-path.

Grandpa Wilmot contended that half a century of leading a cow and her progeny through a yard constituted a permanent right to the cow-path, but Grandma Smith held an exactly opposite view. She therefore took her rocking chair to her side of the hole in the fence and sat there knitting, while Grandpa Wilmot took his rocking chair to his side of the fence and sat there reading, holding the cow by the bridle and ready to lead her to water the moment Grandma Smith moved away from the fence. When Grandma Smith was away he hastily led the cow to water and back again, and in this way the poor cow often secured enough water in one day to last for several days. Otherwise the poor cow would have died of thirst.

When Edgar Smith learned that my grandfather was acting in this manner he quite naturally refused to let me marry Kate Smith, knowing that nothing but quarrels would come of it, but we two young lovers were frightfully depressed. I spent whole days at my window, facing the Smith's home and playing mournful tunes on my cornet, and at times my sorrow caused my mouth to tremble so much that I could not lip the cornet, and my tune would die in a soul-racking wail. My Kate was so sad she could hardly nerve herself to jiggle back a tune on her mandolin. Even Amos Hopstone's callous heart was touched by my weeping cornet, and time and again he got out his pistols and aimed at me from behind a tree, but his hand trembled and he never shot at me.

The happiness of the Smith home was gone. Kate wept almost constantly, although her tears rusted her mandolin strings, and Edgar Smith was angry with both Grandfather Wilmot and myself. Even Amos Hopstone began to show ugliness. He seemed to think I should be digging up Gibsmiths instead of pouring out my sadness through the cornet. His clothes were now all in rags, and as he still gave me his wages at the end of each week he was obliged to sell his two pistols and his bowie knife that he might buy garments.

Kate wrote many letters praying Grandma Smith to sell her farm and come to Westcote to live, but Grandma Smith absolutely refused. She said she meant to sit at the break in the fence until the case was decided in the courts, which -- with the appeals -- might be twenty years. At length Edgar Smith went to New Hampshire himself, and there, although it was midwinter, he found his mother wrapped in blankets, with a red knit hood on her head, hut still sitting by the gap in the fence. Every five minutes her maid brought a hot brick from the house and put it under her feet, but the time passed slowly, for she could not knit with her hands in mittens. When Edgar Smith saw it was useless to argue with her he returned to New York and sent his mother a phonograph with which to lessen the tediousness of the days by the fence. But his thoughtful kindness was wasted, for after trying the phonograph a few times Grandma Smith put it away. She found it amused Grandfather Wilmot too, while she had all the trouble of winding it and putting in new records. All he had to do was sit and listen.

"Poor Kate!" said Mrs. Edgar Smith when she heard the result of her husband's journey. "The poor child is pining away!"

"No fault of mine! " said Mr. Smith. "That young fellow's grandfather is milking all the trouble!"

"That is true," said Mrs. Smith, "but Kate is so sad. She has not touched her mandolin for a week, and whenever Samuel begins to play the cornet she puts cotton in her ears."

"So do I," said Mr. Smith.

I will now make a confession. For over a year I had been concealing from Edgar Smith and Amos Hopstone the fact that I had completed my labors on the genealogy of the one and of the other. True, I hated to take Amos Hopstone's wages week after week, and I may have had no right to withhold his genealogy of the Gibsmiths, but I thought I was doing it all for the best. Now, however, I was filled with rage against Edgar Smith and all his kith and kin. If I might not be happy, and the Smiths might not be happy, Amos Hopstone should, at least, be happy.

When I rang the doorbell at Edgar Smith's house Amos Hopstone answered it. He was neatly dressed in a pair of cowhide boots, khaki trousers, blue cotton shirt sleeves and a waitress's apron with ruffles. The improvement wrought on that rough diamond by association with one of the best families of Westcote was apparent at a glance, for on top of his neatly brushed black hair he now wore a dainty cap with blue bows. He led me into the parlor.

"Amos Hopstone," I said, "I have good news for you. I have found the family connections of old Pete Gibsmith! "

Tears filled Amos Hopstone's eyes.

"Ah!" he cried with joy, "tell me the name, and I will exterminate it! Only whisper it in my ear and I will wipe it off the earth!"

"Smith!" I cried, watching his face. "The name is Smith!"

For a moment Amos Hopstone stared at me speechlessly. His mouth fell open so wide that I could almost see his inmost thoughts.

"Smith!" he muttered. "Smith! Why, there are thousands of Smiths! There's hundreds and thousands and hundreds of thousands of Smiths, and only one Hopstone left!" He began to weep. "I'm scared I won't last 'til all them Smiths is killed off."

"Courage! Courage, Amos Hopstone!" I cried. "Do not let mere mass and number discourage you. With systematic methods you can accomplish wonders. Without systematic methods I should never have discovered that old Pete Gibsmith's name was, in fact, Peter Gibb Smith, or that his father, John Gibb Smith, was the common ancestor of all the Gibsmiths and of your employer, Edgar Smith."

Nothing I could have said would have so quickly made Amos Hopstone himself again. He jumped to his feet, wild with avenging anger. He tore his cap and apron off and threw them on the floor with a gesture of rage. With a rapid motion of his hand he uncurled his mustache and mussed his prim hair.

"Hah!" he cried. "And them in this here house! I ain't got no gun, but I've got an axe!"

The thought that these Smiths, who had so long thwarted my love, would soon meet their fate filled me with unholy joy, and I was about to bid Amos Hopstone do his worst, when Kate passed the parlor door. As she passed she happened to see me, and the next, moment she was in my arms, calling me her Samuel and clinging to me with all the love a mandolinist can feel for a cornetist of no mean ability. At that moment, while Amos Hopstone stood embarrassed by the sight of so much love, an awful thought came to me -- Kate was, herself, a Smith! What had I done! I had doomed my one and only love to the fate of the Gibsmiths at the hand of Amos Hopstone.

"Stop, Amos Hopstone!" I cried, as he was about to dash from the room to find his axe. "Stop! Is this the patient, systematic method I advised? Would you go at your killing like a wild animal, dashing here and there, killing at random? Do not be a fool, Amos Hopstone! While you were exterminating youngish Smiths the oldest Smiths would die peacefully in their beds, escaping your avenging hand! Wait! Here is a list of all the Smiths now living east of the Mississippi and north of Mason and Dixon's line, beginning at the top of the list with the oldest living Smith. Take it! For the list I shall make no extra charge, but if you will accept the advice of a systematic man, you will begin your feud killings with the oldest Smith and proceed to kill them off in the order of their ages. Thus not a Smith will escape! "

Amos Hopstone hesitated, and I saw I had impressed him. He took the list from my hand. Luckily, Edgar Smith, his wife and my Kate were well down toward the middle of the list.

"One thing more!" I cried. "You say you have no gun. I have a gun. Let me aid you in your vengeful work by presenting you with a gun."

"Thank you!" said Amos Hopstone, with tears in his eyes.

Cruel as this offer of mine may seem, as regards the Smiths, it was not in reality so. The gun, although doubtless an excellent one in its day, was not in the best of condition. Indeed, my great-great-grandfather had discarded it just after the Revolutionary War as being too inaccurate to use. My great-grandfather used it for years as a crowbar, and my grandfather and father had used it during their lives as a stove poker, and for the four years I had been boarding my landlady's helper had used it to poke clinkers out of the furnace grate. It was a flintlock musket, and I still possessed a handful of flints and the powder horn that went with the musket.

That evening Amos Hopstone called for the musket, and when he held it in his hands he looked at it rather disappointedly, but he said he would take it. He said he guessed it would shoot further than an axe, anyway. I doubted this, but I said nothing. When Amos Hopstone left my door that night with the musket under his arm, the handful of flints in his pocket, and the powder horn slung over his shoulder, it was the last time I ever saw him.

The next day I took a copy of the list of Smiths to Edgar Smith. He received me sullenly.

"I suppose I've got to pay you for this," he said, "but this branch of the Smith family is going to the dogs, and the more ancestors it has the more ashamed of itself it ought to be. Kate is pining away, and my wife is about sick over it all, and now Amos Hopstone has gone off without so much as giving us notice! "

He seemed so depressed that I thought best not to tell him why Amos Hopstone had left. Neither did I think it an opportune time to call his attention to the fact that Grandma Smith's name stood at the very top of the list of all the Smiths. I merely mentioned that he now owed me the first payment on his genealogical tree. He immediately ordered me out of the house. His cup of trouble seemed overfull.

But the last week in January a new worry came to him. He received a letter from Grandma Smith in New Hampshire. The penmanship was cramped and uncertain because Grandma Smith had written the letter in the open air with woolen mittens on her hands.

"My dear son," it said, "I am in good health, but nervous. That old jackanapes Wilmot still sits on the other side of the fence with his cow in hand. But do not imagine I am afraid of him. I am worried about something else. About the first of this month an uncouth man with black hair and brown pants came to this neighborhood, and every day he hides behind a tree across the road and shoots. I have no idea what he is shooting at, but he is a reckless shooter. Several times a bullet has come into my yard. I am worried. He shoots all day, and the noise annoys me. I believe he is insane."

A few days later Edgar Smith received a second letter.

"My dear son," it read, "that crazy man is still here, and I am sure now he is crazy. This morning he crossed the road and rested his gun on my fence. I almost believe he is shooting in this direction. Every eight or ten shots he becomes violently insane and throws down the gun and jumps on it. It is making me nervous."

The next day another letter arrived.

My Dear Son:-- I am becoming nervous over the actions of a crazy man with a gun. Today he climbed over the fence into my yard and hid behind an apple tree, and he has been shooting all day. At three o'clock this afternoon he shot that old jackanales Wilmot's cow. I hoped then that he had shot what he had come to soot, but no; he is still shooting. Can he be shooting at something in my yard?

The next day there was no letter, but the day after that there was one.

"My dear son," it said, "I am packing my trunk tonight and I shall start for Westcote tomorrow. I cannot stand this crazy man any longer. He is on my nerves. At eleven o'clock this morning that old jackanapes Wilmot was shot in the leg and was taken away to the hospital, but not before he had said he would buy my farm if I would call off the man with the gun. I accepted a first payment and we shook hands on the bargain while the man with the gun banged away at whatever it is he is shooting at. I still consider that old jackanapes an old jackanapes, however. I reserve that privilege. I am writing this in my dining room, and the man with the gun is outside, leaning on the windowsill and firing into the room. I am tempted to believe he is shooting at me. Only a minute ago when I turned to look at him he asked me, with tears in his eyes, to please sit still. The room is full of powder smoke. I begin to fear that my life is in danger."

When Edgar Smith handed me this letter his face was bright and smiling.

"Now," he said, "our troubles are at an end. You must come over this evening and bring your cornet, and we will celebrate your engagement. The wedding may be as soon as you and Kate wish, and Mrs. Smith has already decided on your wedding present."

"Forks or spoons?" I asked, merrily.

"Neither," said Mr. Smith. "We are going to give you one of those silver-plated things that look like an egg and that are used to stick in the horn end of a cornet so it will not make so much noise."

Thus Amos Hopstone brought joy to two fond souls, and happiness to a home, for had he not started out to exterminate Grandma Smith she would, no doubt, still be quarreling with Grandfather Wilmot, and Kate and I would still be parted. This proves again the value of genealogy.

A few days ago I received a letter from Amos Hopstone, written from a small town in Western Pennsylvania.

"Deer sur," it said, "I've past on to Smith number two. Number wun was bulet proof. Thare's too manny Smiths to waste bulets on bulet-proof wuns when thare so old. Lett hur die of ole age if she wants too. Yours foar vengius, Amos Hopstone."