from Milestones

Casey Puts One Over

by Ellis Parker Butler

A couple of days ago I met my redheaded taxi-garage friend, Mike Casey, than whom in all Westcote no man has one-tenth the native brazen nerve. He was covered with grease, as usual, but was glowing with optimism, and grinned at me cheerfully.

"Well, Casey," I said, "how is the world and Amalia Almayer using you?"

"Fine!" he said. "Amalyuh hasn't spoke a word t' me in five days and sends information by disinterested parties that all is over between us from now until th' day of doom. That fine old Teutonic anti-German, her father, Rudolph Almayer, has given me due notice that if I come within one mile of the parental premises he will bore holes in me with th' choke-bore shotgun he hasn't shot off since 1892. One by one, in continuous procession, the friends iv th' family have approached me with th' sad news that matrimonial connections between Michael Casey and Amalyuh Almayer is as likely t' come t' pass as th' Imperor of Germany is to resign in favor of Mister Wilson."

"And what are you doing about it?" I asked.

"I have ordered me wedding suit," Casey grinned.

"But I thought you and Amalia had made it up after your little quarrel about the tires you stole from under her," I said.

"And so we did," said Casey. "I wint nine-tinths of th' way toward ending th' misunderstanding, and permitted Amalyuh t' apologize with tears on me shoulder, whilst I patted her on th' spinal colyum and remarked 'There! there!' than which no man could do more. 'Amalyuh,' I says, 'now that ye see th' light iv day and have returned like th' lion t' th' lamb, we'll have no more iv this business iv off-again, on-again. Tomorry we'll be married.' 'No, Mike, dear,' she says, 'we will not. Ye were sayin' but a momint ago that ye were that hard up a dollar bill would look to ye like a carpet big enough t' cover th' state iv Texas and lap over around the edges. I come of a fore-sighted ancestry, Mike darlin',' she says, 'and until ye have a goodly sum of money in your pocket there'll be no wedding bells.' That's what she says to me, sir."

"Well, I dare say she was right," I said. "A man ought to know where a few months' rent and food are coming from before he marries."

"Sure!" said Casey. "And, like th' gentle dove that I am, I made no grand objection. There was a reasonableness in her words that I would not dispute. I have no complaint t' make of that. But whin a man takes a lady's advice, and works his head off his neck t' bring it t' pass, and th' result is that she's mad as a hornet, then I say th' unreasonableness iv th' female sex is beyond believin'."

"You mean you hustled around and got the money she insisted that you have, and then was angry because you got it?" I asked.

"That's it," said Casey.

"That was certainly illogical and unreasonable," I said, and I thought so until I heard the other side of the story. I see now that I should have remembered the nerve Casey possesses before I told him anything that could comfort him as my words evidently comforted him, for when I left him he was singing "What's the use of worrying" in the most self-satisfied manner.

When I heard the whole story I found there was more to the quarrel than Casey had led me to suppose. I should have remembered that Casey is one of those lovable, whole-souled egoists who think the world was made for Casey and that whatever Casey does is right. When Casey wants a thing the rights of others are mere petty annoyances. I believe, if it bothered him, Casey would grin and throw the Constitution of the United States into the waste can. At any rate he would get a stub pencil and change its provisions to suit himself.

The first thing Casey did after Amalia -- who is a dear, sweet girl -- had suggested that they ought not to marry until he had a few hundred dollars in spare cash, was to attack old Rudolph Almayer, her father, for a loan. He wanted about five hundred dollars, so he asked for five thousand, and he got nothing.

"No!" old Almayer said promptly. "From me you get nothings! Already when Amalia gets engaged by you, I ain't so glad, but I gifs you money to buy two such jitney taxing-cabs to set up in a good business like you tell me it is. Mit such taxing-cabs you should make plenty money, but right away you soak it into such touring-cars by second-hand and all, and I should worry you ain't got no money!"

"I bought thim t' sell again, whin I have fixed thim up," said Casey. "I'm a fine fixer."

"Sure! Maybe! But me for no fife t'ousand dollars you don't fix," said Almayer. "For no one cent more you don't fix me! For Amalia, when she is ready for the marrying, I gif maybe a nice dress mit a veil and all, but it is plenty. When little Rudolph is born --"

"Do ye mind sayin' that wance more?" asked Casey.

"When little Rudolph is born," Mr. Almayer repeated. "Such a little son will you haf, when you are married already, some day, and for him, when he is born, I will haf maybe a t'ousand dollars to gif. Yes! I vill put one t'ousand dollars by der bank today already, for little Rudolph Casey, your first-born, for him --"

"Fine!" said Casey. "Fine, and thanks to ye! Only, his name will be Patrick."

"Maybe so!" said Mr. Almayer without emotion. "How could I know what his name should be? Patrick or Rudolph, I don't know. Only, for such a Patrick Casey would be no money in the bank; for little Rudolph would be one t'ousand dollars. Today, already, I go down and put such money by der bank for Rudolph Casey."

"H'm!" said Casey. "Whin I come t' think it over, Mr. Almayer, I doubt but you're right. Rudolph he is likely t' be."

Mr. Almayer was pleased -- and showed it -- that Casey was so willing to agree with him, but his satisfaction was not sufficient to induce him to lend Casey the money my redheaded friend wanted, and if Casey had had that in mind when yielding so gracefully, he found he had yielded for nothing. Old Almayer would not be moved. But Casey was not at the end of his string. Casey never was at the end of his string.

Casey went down to his garage and looked over his assets. He had three jitney taxicabs, all pretty much banged up, but he did not for a moment think of selling them. They were his business. He walked past them to where, on the grease-slippery floor in the rear of his garage, stood the "tank." I don't know who first called that secondhand car a "tank," but it was well named. In a week after Casey bought it everyone called it the "tank." It made more noise than those pretty little affairs the Allies are using to crush trenches and walk over villages, but it was not such a modern instrument. The hood contained two cylinders of strange construction and more pipes, wires and trimmings of a complex mechanical nature than the interior of a U-boat. On the forward deck, or bow, of the hood -- so to speak -- was mounted some huge brass instrument like a marine searchlight. This was supposed to cast a light that would carry five or six miles and blind at two hundred yards, but Casey had hooked it up with the electric complexities of the car and when the car was standing still it gave about the light of a candle; when the car was under way this dimmed down to a weak, reddish-yellow pin point. Aft of the hood the body of the car slumped suddenly, because fore-doors had not been invented when the car was made, but it made up for this by rising grandly at the rear, like the galleons of old. There were no doors in the sides of the rear of the tonneau because people might fall out if there were doors there. Somebody might carelessly leave one open. Still, it was necessary for people of an adventurous nature to enter the rear part of the car and, for their convenience, there was a door in the back of the car, with a couple of steps by which the strong and healthy could climb up. The chassis was high above the ground, and the rear seat was high above the chassis, and people sitting on the rear seat and looking over often got dizzy and wondered if they would be dashed to pieces if they fell all the way to the earth.

The engine -- I hesitate to call it a motor -- was complicated, but the maker of the car had been fair and square, and every time he stuck a new sort of doojab in the engine room he stuck another piece of brass on the outside of the car. There was so much brass on the car that the tonneau had to be big -- if it had not been big there would not have been room for all the brass. The tonneau had to be big to make room for the maroon paint.

In the front of the car was a crank and when a man grasped it and bent to the task of turning it, he felt that he was turning over the entire power plant of the Leviathan. He braced his feet and humped his back and grunted. When he had turned the crank anywhere from twenty to thirty times and his eyes were bloodshot and straining out of their sockets, the motor would start with a bang and the fore part of the car would begin bouncing up and down with a noise like a stone crusher chewing steel ingots. When this happened the unfortunate gentleman would rush to the steering wheel, push a small lever hastily and the engine would stop dead. Then the victim of adversity would groan and tackle the crank again. The record of the "tank" was that once out of every forty-eight times it was started the crank broke a man's arm. Men who owned it would do well to hire their hospital rooms in advance, by the year.

The "tank" was such a sweet, light little thing that tires exploded under it when it stood still and at rest. Neither would it have qualified in an economy test. Gasoline ran through the carburetor faster than it could be poured into the tank and one man who had owned it had called it "Rockefeller's joy."

It was, however, when the car started that it became really interesting. If the tires did not explode and the gas had not all run out and the leak in the radiator had not queered the ignition, the driver would climb into the front seat and pull a lever with all his might and there would be a sound like a buzz saw running into a bridge spike. The car would start with a jerk that would dislocate every joint in the driver's backbone. The heads of those in the rear seat would jerk backward and smack the brass trim on top of the rear elevation of the car. A noise like a large audience hissing an exhibition of corn-shellers would begin under the hood; the lids of the hood, the mudguards and eight or ten pieces of brass trimming would begin to rattle eagerly, and the stately galleon would move down the street at a rate between four and eight miles an hour. Just beyond the corner a tire would explode, or the driver would get down from his seat and begin remaking the engine and ignition system from the ground up. The only part of the "tank" Casey had not worked on for days and weeks was the frame of the chassis. That never needed attention. It was made of good solid H-bars, the sort and weight used in building skyscraper.

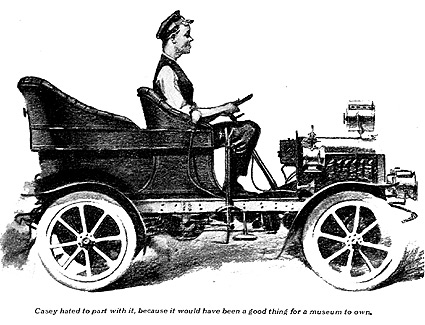

When Old Almayer refused to lend Casey five hundred dollars, Casey started out to sell the "tank." He hated to part with it, because it would have been a good thing for a museum to own, if any museum had wanted to start a collection of automobiles of all eras, but he needed the money. He got into the car and started toward Wayside with his eye wide for a possible purchaser. When he reached the Wayside Garage he stopped the car -- it was never any trouble to stop it; the trouble was to keep it going -- and hailed Ben Haskins. Casey knew what he was doing; if there was anything in the world Ben Haskins would not buy no one had ever been able to discover it. He came out with a wrench in his hand and looked at the "tank." He walked around it, looking at it, and then shook his head.

"What is it?" he asked.

"It's an automobile," said Casey. "It's a mighty good automobile, if I say th' word myself. I've perfected her workin' parts beyond th' belief iv humanity."

"Oh!" said Haskins. "She's perfected, is she? I thought you had fetched her up here to have her mended. Well, what you want me to do, shake hands with her?"

"I'm in need iv money," said Casey. "I want to sell her."

Haskins walked around the "tank" again. He hit the tires with his wrench, shifted a chew of tobacco to the other cheek, and stood off.

"Well," he said doubtfully, "I might give you ten dollars for her, Mike, if you unscrew that headlight so I don't have to do it. She's got plenty of blemishes, but I might go as far as ten dollars for her. I feel sort of reckless this morning."

He had to shout this, because Casey had not stopped the motor. Casey did not exactly reply. He threw in the clutch.

"Well, good-bye, Ben," he said.

"Good-bye, Mike," Haskins said, and went back into the garage.

Casey stopped at the corner and loaded his gas tank and ran back to Westcote, all of three miles. He ran the car into his garage and got down and looked her over. He had paid forty-eight dollars for her and he began to feel -- if Haskins would only give ten -- that he had paid too much. He got a can or two of paint and began painting her royal blue with yellow on the wheels and then gave her a coat of varnish. He polished all the brass and gave her a set of new tires. Then he ran her out to Wayside again. He stopped at Haskins garage once more. "I see you've got the old 'tank' all dolled up, Mike," Haskins said. "Sort of waste of good paint, ain't it?"

"What'll ye give me for th' beauty th' way she stands?" asked Casey.

Haskins walked around the old car again, bumping the new tires with his wrench.

"Notice you took that locomotive headlight offen her," he said. "Improves her looks a whole lot. Real tasty lookin' blue you've got on to her, Mike."

"What'll ye give me for her?" asked Casey.

"Them tires is worth somethin'," said Haskins. "I might go as far as twenty-five dollars, includin' the tires."

"Well, good-bye, Ben," said Casey.

"Good-bye, Mike," Haskins answered. "If you feel that way about it I guess I withdraw the offer. Twenty-five is a lot to pay for an old ark like that. I'd have a lot of trouble gettin' my money out of her again."

He did not see Mike again until the day I mentioned in the beginning, when I was conversing with Casey in his garage. He drove in while we were talking. He stopped his motor -- he had a new car with a self-starter -- and leaned over toward us.

"Ready to take twenty-five for the old ark yet, Mike?" he asked.

Casey ignored him.

"And right ye are, sayin' the sex is illogical an' unreasonable," he said to me. "I come up to th' house, with all th' grease washed off me face and me Sunday garments on, and I tell Amalyuh I have th' cash she was wantin' me t' have, and what does she do?"

"What?" I asked.

"All but slams th' dure in me face," said Mike. "'Robber an' thief!' she says t' me, or words t' that effect, and no more will she say but retires into a condition iv vexation an' unreasonableness that would try th' patience iv any saint there is. 'Nerve,' she says, 'may be a grand thing, Michael Casey, but there do be such a thing as havin' enough and a bit too much. And if iver anybody had enough, and more thin enough, and then some spillin' over; you is it!' "

"Why? What had you done?" I asked him.

"Nawthin'! Nawthin' at all but sell th' 'tank,' and provide th' ready cash she was so eager for me t' have."

"You don't mean to say you sold that old 'tank'?" Ben Haskins broke in.

"Iv course I sold it!" said Casey.

"I mean th' one you painted blue," said Haskins. "The one you had up to my garage a couple of times. The one that was born back there in the days when Noah was a boy. That one that made a noise like a skeleton takin' reducing exercises on a tin roof. That one; you didn't sell that one!"

"Sure I did:" grinned Casey.

"What did you get for it? Ten dollars?" asked Haskins.

"Ten dollars!" exclaimed Casey. "I got eight hundred dollars for it, Ben, an' sorry enough I am I didn't stick for more."

It seemed to awe Haskins.

"Eight hundred dollars!" he said in an awed whisper. "Eight -- hundred -- dollars! Who did you sell it to, Mike?"

"Rudolph," said Casey. "Little Rudolph that is to be. I held a long an' convincin' conversation with th' grandfather iv th' lad an' convinced him that an investmint in a classy automobile was better than money in th' bank for th' lad. I sold th' car t' little Rudolph Casey."

I am inclined to think this was being a little too nervy, even for a Casey. Amalia thought it was. It did annoy her to think that Casey would sell a car to their still non-existent and entirely hypothetical little Rudolph.

"Even if he should talk papa into buying for little Rudolph a good car I could be mad at him," she told me, with a blush, "but when he talks papa into buying for little Rudolph that bunch of junk for eight hundred dollars and makes papa a present of the other two hundred out of little Rudolph's thousand dollars, for a commission to him, like, I ain't ever, ever, ever going to speak to him again so long as I live! Not for a couple of days yet, anyway!"