from Dearborn Independent

Breaking Into Literary Game

Searching for '..."Breaking Into Literary Game"...'

by Thomas L. Masson

It must have been fully thirty years ago that Ellis Parker Butler, author of Pigs Is Pigs, came into my office in New York one day and asked me to cash a check for $150. He was from Kansas City. He explained to me that he wanted to break into the literary game, and someone had suggested to him that as the literary editor of Life I was the man to see.

Even during those days I had had a long and extensive experience with literary borrowers, but this young fellow coming out of the West looked like a genuine product of the soil, and I readily gave him the money, particularly as the check he presented was a draft on a New York bank.

He explained to me that he had a girl "back there" and he purposed to marry her as soon as possible -- after he had made his fortune as a writer. He had $150 in cold cash as a starter and asked me how far he could make it go. He was entirely alone and had never been East before.

I told him to get on a surface car going north and not to get off until he saw green. Unfortunately I had entirely overlooked Central Park. He obeyed my advice literally and when he saw green, got off in the park and wandered about among the swans, until he learned from a policeman where he was. Being afflicted with native intelligence, he surmised that a New York editor never got things right and that I probably meant farther on. So he got on another car, and rode and rode until he came to 180th Street. There was green there then. He got off, went to the nearest drug store and made inquiries about a boarding place. They gave him an address; he settled down there and started in to write. He didn't succeed at first.

For several years he submerged himself in a trade paper, acquiring valuable business experience and also a writing technique. He had a great sense of humor and a capacity for industry. The Pigs Is Pigs idea, as a short joke, had originally been printed in Punch. Butler seized upon it and gave it its proper setting in an American story of great natural humor.

Meanwhile, he had married the girl and was raising a family. He went to Paris on the proceeds of his book (a new edition of which by the way has just been issued -- the latest after twenty years) and lived there for a year. But he couldn't write in Paris. And so he came back, and hundreds of thousands of readers now know who he is and delight in his work.

During the last thirty years I have had under observation hundreds of lads and lassies who have attempted to break into the literary game, and I can almost always tell whether they are going to succeed or not in one interview. But in case anyone wants to know, I hasten to say in my own defense that I am much too busy to read long amateur manuscripts from strangers or to sit on any set of eggs furnished by budding geniuses. All I can do is to point the road to success and to show why failure is more or less inevitable. All I can do is to round up here the elements both of failure and success, and let you think it out for yourself; remembering, and indeed emphasizing, that there is as much bunk about the literary game as about any other game.

In strong contrast to the case of my friend Ellis Parker Butler is the case of a young man I now have under observation. Without giving his name, I mention him as a typical case of what I term maladjustment to environment.

This young man is an Englishman, twenty-five years old, an Oxford man. He had had a severance of friendly relationship with his father, a wealthy British subject, this boy being his only son. The boy told me, during the second interview I had with him, that so far as he could judge, American fathers understood their sons better than "at home."

I asked him just what he meant by that.

"Well," he replied, "we don't get on together. I never had a word with my governor. We simply didn't talk. He sent me about a good deal, but he ridiculed me when I was not present, and that wasn't cricket. He might send me a remittance and he might not."

This boy was born of literary antecedents. His uncle is one of the most distinguished novelists of the immediate past generations -- a "household word." He had traveled about a great deal -- the Orient, Europe generally, and so on.

Here he was in New York, with a fine education, with letters of introduction to publishers and editors, all of whom smiled flickeringly upon him and told him to "drop in" later and maybe they could do something for him. There is nothing of the highbrow about him, but he cannot adjust himself to his environment for many years. Meanwhile, he will struggle along, gradually finding himself. If it took Ellis Parker Butler years to adjust himself, to acquire his technique, and he a native, it is obvious how much harder it is for an outsider.

It is the psychic gift to become a part of one's racial atmosphere, united with the power to express it, that makes the writer.

And, as an asset, it is the ability to be casual that counts. You must work like fury intensively, and at the same time keep well on the surface of things. People will read what you write when you hit off your own feelings toward your world by touches, as if you were playing a harp, thus awakening in them corresponding emotions. This business must be casual, it must carry a smile with it.

Another case: During the war a young lad, with a bright handsome countenance suggestive of the Celtic, called at my office. He had been in battle, and was now on a furlough. His name was Percy Crosby, and he was an artist, or thought he was.

From a side pocket, he drew a bunch of soft paper, and spread the pencil sketches on my desk.

These sketches had been made in No Man's Land. Lying on the ground, with the detonations of shot and shell around him, while waiting to move, he had amused himself with these fancies -- human beings in action.

They were terribly funny -- crude, but what of that?

I was afraid he would spoil them if he did them over within the mechanical atmosphere of a modern studio, or wherever he worked. And so they were reproduced, with some difficulty, just as he drew them.

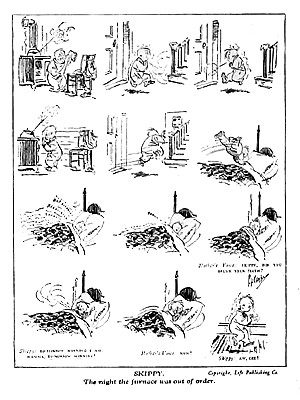

That was Percy Crosby in 1916. He returned to the front, and when the war was over, created his Skippy, now so famous. Boy stuff.

The secret of all creative work lies in the spirit of play. The author must enjoy what he is doing.

If we go to England, and visualize the long line of characters in English literature, we shall be surprised at the result. In Punch, Leech created Briggs, and before him Hogarth created the Rake, and there are many others of minor importance. Generally speaking, however, the artist in English literature has been subordinate to the writer, merely serving to picture the writer's creations; although in the case of Dickens, it seems to be fairly well established that the artist Seymour did actually suggest Pickwick in some sketches he made during the period when Dickens was a reporter. Here is a case where the writer seized upon the idea drawn for him by the artist.

Since the war there has been an amazing increase in the number of writers, this being due to prosperity, which in turn has induced more general leisure. The result is that thousands of young men and women all over the country are turning their faces toward the writing game. And what they all want to know is how to break in.

The best way to answer this question is to tell some stories.

Several years ago a young fellow brought me a manuscript, and at the same time applied to me for advice. His work showed that he had talent, and I told him what I generally say to applicants: "Will you do what I say for two years?" He said he would. In two years he had become a successful contributor. Then he came to me and said he had been offered a regular position as a dramatic critic. I advised him not to take it. He disagreed. Since then he has developed as a minor critic but has entirely lost his ability to write creatively. If he had kept on he would probably have had a hard time to support himself, but gradually he would have acquired an increasing reputation. As it is he will run a submerged course. This is a case of buried talent.

Clyde Fitch, one of most successful playwrights, after a long preliminary apprenticeship, found himself one year returned from Europe with no resources, and rather completely discouraged. In desperation he thought of Life, because in those days it chanced to be the easiest and quickest source of immediate publication for a writer. He wrote a series of conversations, and told me afterward that before coming into my office, he walked around the block several times. We accepted his manuscript and gave him a check for $250. This was the turning point in his career. It gave him just the start he wanted. From then on he began to write some of the best plays then produced. He died too young. He was a very talented writer.

This "turning point" is the critical period in the life of any writer. It almost always occurs. By this I mean that every writer can almost always look back to some period (it might have lasted only fifteen minutes or have taken up a day) when he suddenly came into his own. This does not mean necessarily that he succeeded immediately but only that he recognized his coming success from that moment -- in short, found himself.

Many years ago I picked out of the mail one day an envelope with a single short manuscript in it. I saw that the man who wrote it had undeniable talent, but that this particular copy was unavailable. I sat down and wrote him a personal note, in which I made the prediction that within ten years he would be known all over the country. He wrote me afterward that he was completely discouraged up to the time my letter came. His father and mother had come to visit him, and he had nothing to say. But the very day they arrived he received my letter. It just happened that way, I suppose, but I have seen like incidents happen so often that it is almost uncanny.

This writer was McCready Huston, whose work as a short story and novel writer is so well known.

In breaking into the literary game, several thoughts stand out. The first one is this: As a rule those who have come to me for advice without first producing something good have seldom if ever been successful afterward.

The reason for this is that people who want to write, and seek advice without production, are almost always selfish even if unconsciously so. Or else they are hard up, and think they can make money this way. Nothing can be done for such individuals. If, for example, I show them a method of writing, and give them ideas, and they go to work and produce the thing according to my suggestion, it is never their own. And when they come back with it, and I explain to them why it will not do, they invariably resent criticism. They generally remark that they have seen so many worse things than that in print. They do not understand that what they think is a "worse" thing always has in it a germ of originality, of sincerity; in short, it is an honest product, as defective as it often is. In other words, a successful author writes from his emotions, and not from his intellect. He uses his intellect -- his formal brains -- as an assistant, a kind of secretary, to his feelings. In this capacity, intellect is not only important but necessary. But it can never take the place of genuine feeling -- the glow of the true artist.

This glow can almost always be felt by a true editor.

There is no difference in principle between the judgment of writing and of pictures. But there is a great difference in appearance. Thus when you look at a picture, you can tell at a glance whether it is good or not. The amateur qualities and crudities stand out in it, so that almost anyone, even if he is not trained to judge, can tell its defects.

But a manuscript may be crude, may seem very bad, and yet, to a trained editor, may still contain the essence of genuine talent.

Recently a gifted woman sent me a manuscript which had hidden within it this rare thing. I took a blue pencil, cut out the first two-thirds, put a new title on it, and returned it to her. She sent it back to me and I accepted it. She wrote me that my alterations and devastations had taught her more about writing than she had learned in years. It was in effect only Dr. Johnson's rule which every writer should observe: After writing a thing, go over it and cut out every other word.

It is absolutely necessary for a writer to have talent -- or call it a "gift." Admitting this, however, nothing is more important than the technique, and, judged from the enormous number of carelessly written manuscripts I get from amateurs, it would seem as if this were a universal American fault -- carelessness in construction.

Now the preparation of copy for publication does not necessarily consist in perfection in letter press, but almost wholly in the care displayed by the writer in thinking out beforehand, or in critically revising beforehand, just what he has written.

And the very first matter of importance lies in the title.

It is almost impossible to overestimate the importance of the title. For instance, a very large part of the enormous success which followed the publication of Anita Loos' Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was due to the title.

A technical rule for titles suggested, as I recall, by Gelett Burgess some time ago is, where there are two words, to have the initials follow alphabetically.

There are, of course, many exceptions to this, and it relates only to sound. For example, Sinclair Lewis' latest novel, Elmer Gantry, follows this rule, the letter g following alphabetically the letter e in Elmer, the f between not counting, it merely being a general principle of word sound that you get better results if you use the succession of words in the alphabet.

The point made by advocates of this rule is not to follow it literally, but to use the alphabet-succession as one means to get effective harmony. In Samuel Clemens' pen name, Mark Twain, the t follows the m but at a distance, whereas, in one of his titles, Huck Finn, the h is put first, out of the succession. This rule, of course, is wholly disregarded in cases like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, as in this title the effect does not depend on the sound but on the meaning. The same thing is true of another popular book, The Private Life of Helen of Troy, for this title carries what is termed an appeal, because it suggests something possibly scandalous; that is, it awakens curiosity.

And this awakening of curiosity is one of the most important things in a title. Alliteration or alphabet-succession or any other sound does not matter compared with this.

I have seen numerous manuscripts accepted, even if afterward they had to be altered or even rewritten, on the strength of the title. And this applies to every kind, the very short as also to the very long. A title must convey, and this instantly, the genius of the article or story. What a title is Poe's The Gold Bug! That there is an unconscious psychology about titles is shown in the frequent repetition of words in titles by different authors. One example is enough. Booth Tarkington's The Magnificent Ambersons (1919) was followed in 1921 by Joseph Lincoln's Galusha the Magnificent and in 1924 by Rafael Sabatini's Bardelys the Magnificent.

I know a number of writers who will never start a manuscript until they have first created a right title. In fact, it is never safe to do so, because if you cannot get a title, it is almost always evidence that your theme is not vivid in your mind. Of course, the acceptance of a manuscript generally must depend upon the idea, and this idea depends upon its immediate fitness, whether it "hits off" the prevailing national mood, or what the editor or publisher thinks is the prevailing national mood. There are further considerations such as length, and the possible amount of similar material. But aside from all this, and assuming the requisite talent, the technical success of a manuscript, assuming a right title, depends upon two words, namely, spontaneity and revision.

Now it is a singular thing in writing, and I am sure this will be agreed upon by the majority of best writers, that spontaneity is achieved in its greatest measure only through previous preparation. Spontaneity comes only as a result of overflow. By overflow, I mean that a writer, by fixing his mind on his theme, gets so surcharged with it that he has to get rid of it, that is, write it out. Thus, in evolving it he is carried away.

The immediate result of this is always a dangerous moment, especially in the amateur, because, being so carried away, he is much too likely to think, after an immediate reading, that he has done a great thing. It may be so. But generally it is not so. The next thing to do, as I have explained often before, is to let it cool off; and, after a reasonable period to go over it again when the right perspective is possible.

The human mind, however, can be disciplined to an incredible extent. And I actually know writers who can go through this whole process mentally, and complete their work, before it is written. First they get their theme; they have trained their imaginations so that they can flood themselves with it; they then -- all mentally -- arrange it in its permanent form. Finally, when they write it out, they have to make scarcely any changes.

Almost all big writers have astonishing memories. They carry not only the entire structure of a story, but also the very order of words and sentences in their minds, and can do this while they are reasserting their words.

In my judgment, this accounts for the difference in apparent facility among writers, but not altogether, because some of them, who write very carelessly, succeed because they have the popular touch. Generally, however, a successful writer if he seems to write fast, has matured his work mentally beforehand.

There is no better test of writing than reading it aloud. If you shrink from doing this, it is a very good sign that it is not worth printing.

It is also excellent practice to read your manuscript aloud to yourself, as if you were addressing an imaginary audience. By listening thus to the sound of your own voice, you can often tell where the weak spots are. One of the most successful writers I know follows this rule, never allowing a manuscript to go out without this test.

The whole secret of writing is that you must present the other man with something not only that he wants but that will do him good. You may be doing him the greatest service at a critical time just by entertaining him.

Writing is like that: not to use the other man to further your own interest, but to further his own interest by interesting him.