from Cosmopolitan

Geoffrey's Panklaggephone

by Ellis Parker Butler

If you can't pronounce it, never mind; neither could Casey. It is a sort of amateur Greek word that Geoffrey made up himself, so it would fit in the same list as telephone, phonograph, cinematograph, megaphone, and so on; and Casey was no Greek. Far from it. If you had mentioned Demosthenes and Solon to Casey he would have said, "Sure now, an' I dunno anny av thim fruit-stand fellers." All he knew about Greece was that it was somewhere in Italy, where the dagos and Portuguese come from.

As Casey came along one morning on his way to his boiler-shop he noticed that a sign was being painted on the small factory next door; and when he went home that night he saw that the sign was complete, "The Geoffrey Panklaggephone Company." By the name he guessed carelessly that it was a company to make either some new-fangled moving-picture machine or a patent medicine, and forgot all about it. When a man is trying to run a boiler-shop these days he has his hands full with that. He hasn't time to stop to stufdy out Pan -- panklag -- pan-whatever-it-is. No, sor.

The way that Geoffrey got the name was this. He looked up "noise" in the dictionary, and it didn't have a Greek root, so he found a synonym, "clangor," and he looked that up, and that did have a Greek root. He had to have Greek in the name. The word was "klagge," so he took "klagge" and tacked "pan" on one end, to mean that his machine was good for all kinds of noise, and then he stuck "phone" on the other end, because that never seems to do any harm, and makes a good ending for any sort of newfangled machine; and there he had his word -- "panklaggephone." It didn't mean anything, but it looked whooping on a sign. That was just the kind of word Geoffrey wanted; the kind a man like Casey couldn't pronounce. It looked as sweet as "vitagraph."

It is wonderful what simple little things hide under big names, sometimes. There Geoffrey had worked out that tremendous word for his machine, and the machine was just a simple little everyday invention, a noise-absorber. Nothing more. Just a noise-absorber. Anyone could have invented it. Geoffrey happened to think of it first.

The whole thing was so simple that it was almost childish. I can describe the panklaggephone in a very few words, so that anyone can understand it and, if he desires, make one himself. The idea is simply this: If we have too much water anywhere, and we want to get rid of it, we get a sponge. A sponge is a water-absorber. If we have too much electricity and want to get rid of it, we get a storage battery. A storage battery is an electricity-absorber. If we have too much money and want to get rid of it, we get an automobile. An automobile is a money-absorber. But what Geoffrey wanted to create was a noise-absorber. Water makes a noise, electricity makes a noise, money makes a noise; therefore Geoffrey built a machine that was something like an automobile, something like a storage-battery, and something like a sponge. Having done this, and found that his model worked all right, Geoffrey formed his stock company, rented the factory building, and began making panklaggephones.

Great is modern science! A friend of mine went out the other day to kill a man who had insulted him. He took his rifle, which was the new soundless kind, and loaded it with smokeless powder. He walked up to within twenty feet of his enemy, aimed full at his heart, pulled the trigger, and shot him dead. All his enemy did was to say, "Don't point that gun at me!" No smoke from the gun, no sound from it, how was the man to know he had been killed? My friend went up to him and told him he was dead, that he was shot through the heart, and still he wouldn't believe it. No smoke, no sound -- he simply couldn't believe he was dead. My friend showed him the hole he had shot in him, and that it was a new hole, but the fellow was still skeptical. He didn't weaken until my friend got a paper and showed him an article about soundless guns and smokeless powder, and even then he said he half believed it was a newspaper fake. But he hated to disoblige, so he died. But he wasted half an hour of my friend's time uselessly. It was one of the fruits of ignorance. It was the same kind of ignorance as that which afflicted Casey.

Casey's boiler-shop was built on the principle that seems most approved for boiler-shops -- the reverberant principle. In a boiler-shop of that kind, if you hit a saucepan with a tack-hammer the sound will boom up to the ceiling, and echo back along the walls, and roll up and down, multiplying as it goes, until it is making as much racket as a Wagner crescendo. But if you put two men at work on a big iron tubular boiler in that sort of shop, one man inside the boiler and one outside, both with heavy hammers, the utmost limit of slam-bang noise is reached. Casey had forty-one men at work in his boiler-shop

When he went up to a workman and shouted in his ear at the top of his lungs all the workman could hear was the warm breath of Casey on the back of his neck.

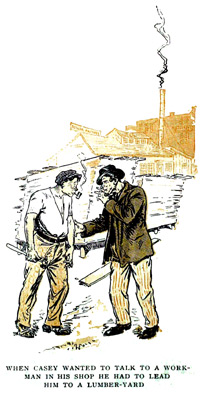

When Casey wanted to talk to a workman in his shop he had to take him by the sleeve and lead him one block east and two south, and draw him into the recesses of a lumber-yard. Over by the front door of Casey's boiler-shop was the machine that takes the flat plates of boiler-iron and rolls them into cylinders. It was a pretty good noise-maker, too. Off to one side of that machine was Casey's own boiler, the one that ran the machines in his shop, and it was a boiler Casey was proud of. It was the first boiler he had ever made, and it was breaking the age-record for boilers. Everyone said it was already ten years beyond the utmost age-limit for boilers, and it was patched up with squares and oblongs of riveted iron until it looked like a cylindrical crazy-quilt. Everyone told Casey he ought to have a new boiler. Every time he took a workman one block east and two south the workman would give notice that he was going to quit unless Casey got a new boiler. They told Casey it wasn't safe to work in a shop where there was an old, rickety boiler that leaked so it put out the furnace fire. Then Casey would say he guessed he'd make himself a new boiler as soon as he got time; but he never got time, and the next time he had a chance to speak to the workmen they would tell him it was absolute suicide to carry seventy pounds of steam in that old teakettle; that forty pounds would be dangerous. Casey stood it as long as he could, and then, one morning, he called all his workmen together and made them a speech. He said he had been making boilers before most of them were born, and knew more about boilers than any man in the country, and that they need not be afraid of that boiler if he wasn't.

When Casey wanted to talk to a workman in his shop he had to take him by the sleeve and lead him one block east and two south, and draw him into the recesses of a lumber-yard. Over by the front door of Casey's boiler-shop was the machine that takes the flat plates of boiler-iron and rolls them into cylinders. It was a pretty good noise-maker, too. Off to one side of that machine was Casey's own boiler, the one that ran the machines in his shop, and it was a boiler Casey was proud of. It was the first boiler he had ever made, and it was breaking the age-record for boilers. Everyone said it was already ten years beyond the utmost age-limit for boilers, and it was patched up with squares and oblongs of riveted iron until it looked like a cylindrical crazy-quilt. Everyone told Casey he ought to have a new boiler. Every time he took a workman one block east and two south the workman would give notice that he was going to quit unless Casey got a new boiler. They told Casey it wasn't safe to work in a shop where there was an old, rickety boiler that leaked so it put out the furnace fire. Then Casey would say he guessed he'd make himself a new boiler as soon as he got time; but he never got time, and the next time he had a chance to speak to the workmen they would tell him it was absolute suicide to carry seventy pounds of steam in that old teakettle; that forty pounds would be dangerous. Casey stood it as long as he could, and then, one morning, he called all his workmen together and made them a speech. He said he had been making boilers before most of them were born, and knew more about boilers than any man in the country, and that they need not be afraid of that boiler if he wasn't.

He said he had had that boiler years and years, and it had never exploded yet, and that he was tired of having men, in his shop, work with one eye on their job and one on the old boiler.

"Go awn back t' worrk now," said Casey, "an' whin ye see me makin' fer th' door 'twill be plinty av toime fer ye t' think av th' boiler bustin'. Pat Casey is th' biggest coward av th' lot av ye, make sure av that."

Then he went around behind the boiler and changed the gage so that it registered forty pounds when it was carrying seventy, threw a cup of kerosene into the furnace to encourage the fire, and forgot all about it.

The third day after the sign of the Panklaggephone Company was painted on the wall of the building next door to his boiler-shop Casey got down to work early. It was his custom. If he had any orders to give it was necessary to give them before work began, so that they might be heard.

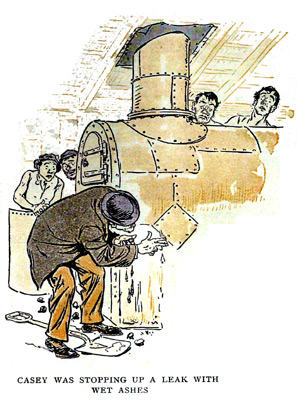

One by one the men dropped in, and when Casey blew the whistle they set to work, all at once and heartily. It was a grand noise; forty men pounding on boiler-plate with heavy hammers, and one rolling steel plates through the machine. It was the climax of clangor. It was so noisy that not a sound could be heard; it was roar! Bang! Clank! Continuously, without intermission. Each man was making so much noise himself that he could not hear any other man's noise. Casey was behind his boiler, stopping up a leak in a seam with wet ashes.

Suddenly a look of anger darkened his face. Silence, utter silence, had settled over the boiler-shop. Casey knew what was the matter. The cowards had taken fear of the old boiler! Rage filled his heart. After him making them a speech about it, too! He took off his greasy felt hat and threw it down and stamped on it. He pulled off his greasy coat and threw that down and kicked it. He rolled up his sleeves and doubled up his fists, and stepped from behind the boiler. He yelled the war cry of all the Caseys. Then he stopped short. Not a man was gone from his place. Not a man had stopped work. Everywhere hammers rose and fell against boilerplates. And everywhere was absolute silence. Not a sound; not a murmur. Absolute silence.

For one minute Casey stood absolutely still, and then a pale, scared look came over his face. He glanced around cautiously -- no one seemed to be observing him. He swelled out his chest and yelled twice, like a scared jackal, but he could not hear his own yell. He could not hear anything. He began to perspire.

There is so much noise in a boiler-shop that often the boilermakers cannot hear the noise. Casey was pretty sure he had gone suddenly deaf, but he was not quite sure. With a cautious motion he bent slowly down and picked up a square of boiler-iron and a hammer. If he was once outside the shop and beat on that square of iron with the hammer he would soon know if he had gone deaf. Slowly he turned and stepped cautiously toward the door.

The boilermakers saw him and got there first. Long before Casey had reached the sidewalk the last boiler-maker was on his way to the lumber-yard,

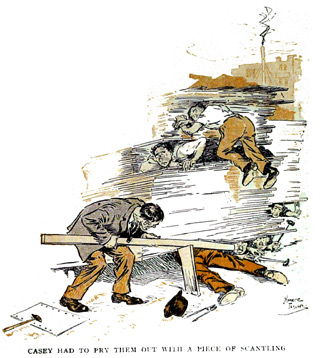

with one eye on safety and the other on the air, where he expected to see Casey's boiler soaring. He was a cross-eyed boiler-maker or he could not have done this. There were plenty of lumber-piles, and the boiler-makers went so far under them that Casey had to pry them out with a piece of scantling.

with one eye on safety and the other on the air, where he expected to see Casey's boiler soaring. He was a cross-eyed boiler-maker or he could not have done this. There were plenty of lumber-piles, and the boiler-makers went so far under them that Casey had to pry them out with a piece of scantling.

"Ye fools!" said Casey, when he had them all out again.

"Aw!" said the foreman; "you said yerself we was t' git out when we seen you git out. Wasn't you gittin' out?"

"I'll not say but what I was steppin' outside a bit," said Casey, "but I was not runnin'. I was walkin' easy. 'Twas not because av th' boiler I was goin'."

"How was we to know what you was goin' out for?" asked the foreman angrily. "What was you goin' out for, anyway?"

"Nawthin'," said Casey evasively. "I fergit what it was, now. 'Twas nawthin' important, annyhow. Mebby 'twas some wan goin' by I wanted a word with."

"All right," said the foreman sulkily. "All I got to say is it must have been some one you're mighty scared of, by the looks of you when you was goin', for --"

Suddenly the foreman stopped speaking. His lips kept on forming words, but they made no sounds. Casey was walking on with his head down, and, as his words faded away, the foreman turned pale. There was something the matter with his voice, but he did not know what. He glanced secretively at Casey, but Casey was not looking. He tried a few words experimentally, but the experiment worked badly. He whistled. Not a sound. Deaf and dumb both! The scared look gathered on the foreman's face. Casey and his foreman and his boilermakers went back to the boiler-shop as silently as a funeral driving over moss.

"Well, byes," said Casey, when they were all inside, "'twas no wan's fault. Git t' worrk!" But his voice fell silent. Hodges picked up his hammer and hit the side of a boiler. He might as well have hit a roll of cotton batting. He looked at the boiler in surprise. Then he looked at the head of his hammer.

Then he hit the boiler again, and the pale, scared look came upon his face. He glanced around cautiously. Casey was paying no attention to him. No one was. All the boilermakers were pale and scared, and were tapping on their boilers experimentally. Pale and scared, they all went to work. They motioned and gestured to each other, just as they did when the shop was full of clangor. They were like pictures of a boiler-shop and its workers thrown on a sheet by a cinematograph -- all motion and no noise.

When the day's work was ended the workers did not troop out together as usual. They stole away one by one, and they did not go home immediately. One by one they sought their favorite doctors.

"I'm thinkin'," said Casey to his, "there do be somethin' th' matter with me ears, Doc. There be flushes av silence come over me t'day, whilst I'm worrkin' in me shop. Would ye be testin' me ears for me?"

"Step into the operating room here," said the doctor. "Now, let me see, what is your business?"

"I'm Casey, th' boilermaker."

"Oh!" said the doctor, and then turned to the door, where his attendant had come. "A man? Well, have him wait. What is his trouble?"

"He thinks he's going deaf," said the attendant.

The doctor took up Casey's case. He tested him in every known way. He told Casey he had ears so perfect that they were almost marvelous.

"Excuse me, Doctor," said the attendant, looking in, "but there is another man here now."

"What is his trouble?" asked the doctor.

"He thinks he is going deaf," said the attendant.

"Tell him to come in," said the doctor, "and tell the other man to come in, and if any more men come thinking they are going deaf have them come in."

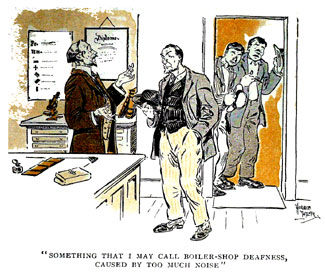

A few more did drop in, soon. They were all pale and scared looking.

"Now, men," said the doctor, when he had examined them all, "you have not a thing to worry about. Your ears are all perfect. Your cases are peculiar, but not inexplicable. I might say that they resemble the snow-blindness that is caused by too much light. You are evidently suffering from something that I may call boiler-shop deafness, caused by too much noise. The nerves of the ear are temporarily paralyzed by too many and too violent soundwaves. In order to prevent a recurrence I advise you to wear earmuffs stuffed with cotton."

At the end of his first manufacturing week Geoffrey had twenty panklaggephones completed, ready for shipment, and he went home to his young wife beaming with happiness, riding beside the driver on the high seat of a delivery truck. Behind him, in the truck, was a full-sized panklaggephone. He was taking it home. It was his wife's birthday present.

Geoffrey had had a panklaggephone in his house, but it had been the model merely, a small affair. It had been enough to prove to him that his idea was a good one, and that the panklaggephone would absorb noises, but the machine had been so small that it left much to be desired. It was strong enough to absorb the noise of a mosquito or two, and had been useful in that way, giving one perfect rest from mosquitoes in the bedroom, until the mosquito really bit; but Mrs. Geoffrey had been losing sleep night after night on account of the crying of her baby, and was growing pale and thin. She knew that the best thing to do was to let the baby cry itself to sleep again, but she was so nervous she could not, and Geoffrey felt that a panklaggephone in the house would be a great boon. It would not only absorb the baby's cries, but the street noises, Mrs. Geoffrey's snores (she would sleep with her mouth open), the crowing of the neighbors' roosters in the early morning, and a lot of other unpleasant sounds.

He and the driver of the truck unloaded the panklaggephone -- it was quite a large affair -- and carried it into the house. They set it, temporarily, in the hall, and Geoffrey touched the button that started the absorber. As he did so he said:

"Now, dear, you will see how it works. You hear the baby crying at the top of his voice" ("I should think I did," said Mrs. Geoffrey) "and all I do is touch this button --"

Geoffrey touched the button. The baby cried louder than before, and his voice was quite as apparent. A frown gathered on Geoffrey's brow.

"That's funny," he said. He pushed the button again and again.

The panklaggephone would not absorb." That's very funny," said Geoffrey.

"Well, never mind just now," said Mrs. Geoffrey. "Here is a telegram that came to the house just a few minutes ago. I opened it. And you must come to your dinner right away if you are to catch the train."

The telegram was from Geoffrey's agent in Chicago. He wired that he hoped to close a contract for one hundred panklaggephones, but thought Geoffrey himself should be on the spot.

Geoffrey hurried through his dinner and then ran to catch the train, and the last thing he said, before he went, was that he would fix the panklaggephone when he got home Monday. He supposed there was something wrong with the mechanism. He did not know that the panklaggephone had absorbed up to its full capacity.

The home of the Geoffreys was in a very refined and quiet section of the town; a section so quiet that, after ten o'clock at night, the steps of the police officer could be heard for several blocks, and when Mrs. Geoffrey went to her dining-room that night at one o'clock to see if she had really forgotten to lock the windows, she was greatly pleased to hear the steps of the policeman on the street before the house. It made her feel much safer. She was always a little nervous when Geoffrey was away.

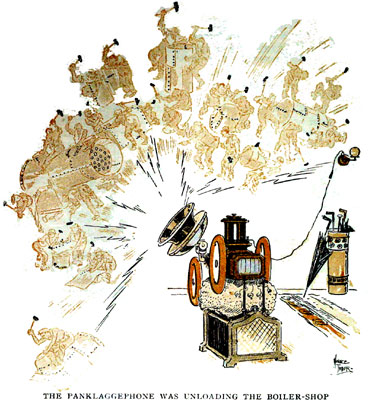

The moment she reached the top of the stairs she paused, listening. From below, somewhere, she heard the sound of a heavy truck jolting over a stone-paved street. Tin-sound seemed to come from the front hall, as if the truck were being driven about the hall itself. Mrs. Geoffrey turned pale, and a scared look settled upon her face. She could hear the heavy breathing of the horses, the crack of the whip, and the creaking of the harness. Then, suddenly, from the hall, came two wild Irish yells, and instantly a boiler-shop burst into full voice. Her ears were deafened by the clangor of metal against metal, of hammer against boilerplate, a wild hurricane of noise, terrific, unbelievable, stunning. Mrs. Geoffrey put her two hands straight out in front of her and fainted backward with a thud that was lost in the racket.

The panklaggephone was unloading the boiler-shop.

The house shook with the noise, and the windows rattled. It was a rude shock to that refined and quiet neighborhood, and the policeman dashed up the steps and kicked in the front door. He stopped, stunned. To the best of his knowledge and belief there were forty-one boiler-makers busily making boilers in that house. There was noise everywhere -- it did not seem to come from any one spot. The house was all noise. He dashed upstairs, and tripped over Mrs. Geoffrey -- not another soul but the baby. He dashed to the garret -- not a soul. He dashed down to the first floor -- not a soul. Not a soul in the cellar! No one in the house but a fainted woman and a baby. And the racket of forty-one strenuous boilermakers pounding on iron with steel hammers! The policeman yelled once and ran.

All up and down the street windows opened and heads were put out. People came forth dressed in nothing much with a spare

sheet over it. The fire department came on the run, and so did the police reserves. Police reserves are useful in keeping people away from places, but there is not much a fire department can do in putting out noises, but it did what it could. It worked on the principle that the noise was coming out of Geoffrey's house, and that if there was no house the noise could not come out of it, so they did what they could to do away with the house. They were pretty successful. A fire department can do a great deal when it tries. Of course there were some pieces of plaster here and there that would not come off the walls easily, but when they turned the hose on them they began to weaken, and they would have had them all off had a stream of water not brought Mrs. Geoffrey to herself. Pat Casey himself helped carry the panklaggephone out of the house when she had explained that the noise probably came from that.

sheet over it. The fire department came on the run, and so did the police reserves. Police reserves are useful in keeping people away from places, but there is not much a fire department can do in putting out noises, but it did what it could. It worked on the principle that the noise was coming out of Geoffrey's house, and that if there was no house the noise could not come out of it, so they did what they could to do away with the house. They were pretty successful. A fire department can do a great deal when it tries. Of course there were some pieces of plaster here and there that would not come off the walls easily, but when they turned the hose on them they began to weaken, and they would have had them all off had a stream of water not brought Mrs. Geoffrey to herself. Pat Casey himself helped carry the panklaggephone out of the house when she had explained that the noise probably came from that.

When Geoffrey reached his office Monday noon he found Casey awaiting him.

"Good day t' ye," said Casey. "Ye're Mister Geoffrey, I'm thinkin'?"

"I am," said Geoffrey.

"Casey's me name," said Casey. "I'm th' man what runs th' boiler-shop that meks th' noise thim machines av your'n has been absorbin'"

"Now, Mr. Casey," said Geoffrey firmly, "I am very busy today. I have been away, and I have come home to find my house a wreck. I am willing to do what is right in the matter, but I really cannot take the time to go over it today. If the absorption of your noise by my machines has caused you any loss my company will pay for it, but --"

"'Twas not that I was thinkin' av," said Casey. "I was wonderin' what wan av thim pank -- thim panic --"

"Panklaggephones?" said Geoffrey.

"Yis; wan iv thim. I was wonderin' what th' cost might be?"

"Certainly," said Geoffrey. "Such a machine should be of the greatest use in a boiler-shop, particularly if this crusade against noise -- Now, we will guarantee to supply one that has not absorbed any noise."

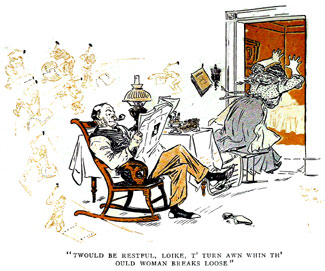

"Do ye know me ould woman?" asked Casey.

"No," said Geoffrey, with some surprise.

"Well, 'twas not wan av th' absorbin' kind I was thinkin' av," said Casey. "I mek out very well at th' boiler-shop; very well. But there do be some toimes whin me ould woman has th' gift o' speech, an' th' house do be annythin' but peaceful an' quiet, an' I'm a man that loikes quiet, Mister Geoffrey. I was after hearin' th' pank -- th' machine goin' off at yer house th' other night, Mr. Geoffrey, an' I would loike t' have wan av thim loaded up with a boiler-shop t' take home. 'Twould be restful, loike, t' turn awn whin th' ould woman breaks loose."