from Gentlewoman Magazine

From Peak to Peak

by Ellis Parker Butler

As Christmas approached Joe Carsey began looking at phonographs and asking their prices because he knew a phonograph was what he would have to give Jessie. Aunt Ella in New York had remembered their wedding anniversary in October and she had also remembered that Jessie liked to dance, and she had sent twelve new phonograph records on which were twenty-four of the newest dance tunes.

"The darling!" Jessie had exclaimed. "Now, we'll have to get a phonograph!"

"If I can make the grade, Hon," Joe said. "Things are going pretty good, but not so good, either. Gimme till along about Christmas, anyway. Maybe we can stand the gaff by then."

"But Joe!" Jessie had said. "That's silly. We've got to have a phonograph; what use are a lot of records without anything to play them on?"

"All right!" he told her. "Christmas, then. Wait for Santa Claus."

When Christmas neared he studied his sales-chart and wasn't happy over it. It wasn't so good. The year before this he had made a nice peak, the red ink line showing his sales having climbed right up to Christmas, but this year it was not climbing as well. Appliances were doing better -- irons, hair-curlers, toasters -- but the staple of his shop, the lamps, were way low. And for a reason. A fellow named Bitterman had opened up and was selling lamps and appliances and some of the trade went there. And always would. Bitterman had come to stay and he was no silly.

There had been the normal increase in lamp use in Westcote during the year -- new buildings, some of the old gas users having their old houses wired, and the expected increase that came because people who once know the comfort of good light always want better light -- but Bitterman got his share of the increase and took some of Carsey's trade. Not so good!

"But Joe," Jessie said when he told her this, "you ought to do something to increase our lamp sales, if that is the trouble."

"I've done it," he said.

"Then you ought to do something else," she said.

"I've done that, too," he told her with a rueful laugh.

"But you promised me a phonograph, Joe," she said. "You did, you know. Every time I see the records Aunt Ella sent --"

"It's lucky she didn't send you an anchor, Jess," he said.

"Why?" Jessie asked.

"You'd want me to buy you a ship," Joe laughed, and that was as near as they had ever come to a quarrel because they were both good-natured.

"But a phonograph is not a ship." Jessie said, "and phonograph records are no use without a phonograph, are they now, Joe?"

"You'll get your phonograph," Joe told her. "I'm not that hard up. And there are still easy-payments, if it comes to that."

So he went back to study his chart again. The phonograph was nothing much. Jessie would get her phonograph, and something else, too. Something unexpected, as a surprise -- a wrist watch, maybe. But a chart that doesn't show new peaks now and then isn't much of a chart. A business ought to grow. And the reason his business did not grow, Joe decided, was Elmus K. Rotherwell.

Elmus K. Rotherwell was a man of sixty-five and he had a jaw like that of a bull-dog -- for business purposes -- but inside of him he had a bull-dog's kindly heart, for family use only. Elmus K. Rotherwell was not only the Westcote Light Company but he was almost Westcote itself. He was the man of money of the town, he owned the Westcote State Bank, and he owned business blocks by the row. He was a wise old man, too. He could take a nicely sharpened pencil and do more stunts with a chart and an engineer's report than Joe Carsey would ever have thought of attempting. In one matter he had used the butt end of his pencil. He had tapped it on his desk and had said. "Impossible! Good day, gentlemen. This is final."

This had been in the matter of the bungalow colony that had sprung up out beyond Cross-county Road, the large and growing group of houses generally known as Wilshire's Colony but sometimes called West Westcote. The land had been a farm -- a large farm -- and a good part of it lay on the hill overlooking the river. When Wilshire decided to lay it out in lots he went to old Elmus Rotherwell and asked about electricity.

"I expect to have quite a colony out there." he said. "I'm selling the land cheap, and I've got some money to lend folks that want to put up medium-priced bungalows. I ought to draw a lot of the young married folks out there -- let them pay me back on easy terms. Now how about running a wire out there and supplying the folks current?"

"Impossible!" said Elmus K. Rotherwell instantly.

"I don't see why," said Wilshire, "All it is going to cost you is a couple of miles of poles and some wire. We wire the bungalows. You ought to sell a lot of current out there. Soon as I can get Westcote to accept the place as an Addition there'll be street lights, and that'll be more current."

"Impossible!" said Elmus K. Rotherwell again. "I do not care to go into details, but it is impossible. I know my business, perhaps I may tell you, Mr. Wilshire, better than you know it."

"You're going to develop that property to east of town," said Wilshire, getting red in the face, "and you want to freeze me out. You want to tie my property down to gaslight and oil-lamp illumination. That's what you're up to!"

"The interview is ended," said Elmus Rotherwell, "and you may bear this in mind -- I am still able to manage my own affairs without outside aid. Good day, Mr. Wilshire."

In spite of this disappointment the Wilshire Colony grew, and it grew rather rapidly. The first bungalows were so pretty and the view of the river was so pleasing that the young couples did build bungalows there. Morning, noon and evening the road along the river was lively with small, cheap cars as the husbands hurried to and from work. The Wilshire Colony became known as the pleasantest place for young couples to live; there was a merry social atmosphere, inexpensive but happy. But no electric illumination!

From his own point of view Elmus K. Rotherwell may have been right. He watched the peaks of his chart and he knew how much current his plant could produce at its maximum. He felt that he was an old man and that he was none too well. He saw the current demands of Westcote increasing each year, peak following peak, each higher than the one before, and he used his pencil. The figures made a neat little example. With his plant's given capacity, the normal growth of Westcote, and his state of health and age, his plant would suffice till the day of his death. And any extra load would carry the peak of consumption off the top of the chart.

A year later a delegation from Wilshire's Colony called on Elmus K. Rotherwell and humbly enough petitioned him to extend his wires to the Colony and again he up-ended his pencil and uttered his stern "Impossible!" He did not go into details. His mere word was final. But he might have shown figures. His plant was an old one and the building in which it was installed was cramped to capacity. He must take care of Westcote in light and power or lose his franchise. His plant could take care of that growth, but if he added outside territory he would have to build a new plant. That he did not want to do at his age. When he died his heirs could do as they pleased, but he was satisfied. He would let well enough alone.

"Joe." said Jessie Carsey, taking her place at the table a week before Christmas, "Kay Willis came to call today. She was the happiest thing! They have bought one of the Wilshire bungalows."

"She won't like it without electric light," Joe said.

"Electric light!" scoffed Jessie. "That's all you think of -- electric light! Bulbs! Why, Joe, she's just tickled that they're not going to have any. She says it will be just like pioneering -- lamps and everything like grandma used to have. She says she just loves to fill lamps; just loves the smell of kerosene. I do think she's the happiest bride I ever heard of -- except me!" she added.

"She's a mighty nice girl," Joe agreed. "Ben Willis was lucky to get her. I suppose old man Rotherwell is buying the place for them."

"He's not, though," Jessie informed him. "He don't believe in coddling them, Kay says. They have to get along on Ben's salary."

"He can't think much of her then; I don't call him much of a grandfather." Joe said. "Him with his million dollars or so."

"But he does think much of her," Jessie insisted. "He just thinks the world and all of her, Joe. I know -- I've seen them together. Joe, they want us to go out real often; they want us to go out tomorrow night and dance. They've got a pho--"

"All right, all right!" Joe said, grinning. "I get the point. You'll get your phonograph. Honest. Jess, I don't blame Sampson and Adam and Mark Anthony -- when you women once get after a man you get what you want, don't you?"

"But you promised me a phonograph --" Jessie pouted. "If I just remind you of it once in a while, now and then --"

Joe lay back in his chair and laughed and laughed.

"You ladies!" he cried. "Talk about --"

He stopped suddenly and looked grave. The transition from mirth to seriousness was so sudden that his face had a frightened look.

"What is it?" Jessie asked anxiously.

"Nothing," Joe hastened to assure her. "Just business -- I thought of something. Something I ought to do. But about this going out to Willis's tomorrow night -- is it going to be an all-dressed-up affair? I've got to get me a new shirt.

"It's informal," Jess said. "Kay said they wouldn't dress; they don't usually.

"I'll get me a new shirt," Joe said.

"And, Joe, you mustn't talk electric light," Jessie warned him. "I mean, Kay won't care but I guess some of them out there are pretty sore about not having it out there, and Mr. Rotherwell is her grandfather."

"I won't say a word," Joe promised her, and he did not.

They had a fine evening at Ben Willis's. Half a dozen of the young couples of the Colony came in and the rugs were rolled up and all danced.

"It's a lovely phonograph." Jessie said to Joe when they were dancing together.

"You're a lovely follow-up lady," Joe said. "Reminder Number Two Thousand Six Hundred and Forty-four."

"Well, Joe, it we didn't have the records --"

"Reminder Number Two Thousand Six Hundred and Forty-five," said Joe.

"Silly!" she laughed. "I'm not worrying; you promised me a phonograph and I know I'll get it."

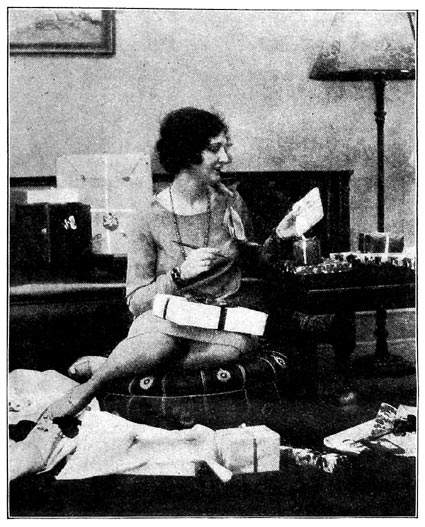

For Christmas, now but a day or two away, Jessie bought for Kay Willis a delightful little brass tray that was just right for the table Kay had in her little hall, but she did not hear from Kay until a week after Christmas -- on New Year's Eve, to be exact. Then her telephone rang and Kay's voice greeted her.

"Jessie, you dear!" Kay cried. "I want you and Joe to come out tonight, will you? For dinner, and we'll dance and sing things and see the New Year in. We're just wild -- we're going to have loads of people in and have a celebration. And thank you ever and ever so much for the perfectly darling present you sent me. It was the nicest thing I got from anyone for Christmas."

"I thought you'd like it," said Jessie. "I was afraid you had not got it, not hearing from you. Joe swore he mailed it --"

"Not got it?" exclaimed Kay. "Why I was out of the house and up at grandpa's half an hour after I got it Christmas morning. Jess, I haven't given the poor man a minute's rest. I've been at him every day, and that's what the celebration is for tonight. He just promised me today that he would run a wire out to the Colony, and now we'll all have electricity."

"But --"

"I'll tell you all about it tonight," Kay cried. "The butcher has come. Tonight! Sure, now!"

"But, Kay --" Jess said to the telephone, but Kay had hung up. Jess turned away and put a dance record on her phonograph.

She had found the phonograph in the living room Christmas morning. But not the wristwatch. Thinking it over Joe had decided he had better wait awhile as far as the wrist watch was concerned, business being what it was and what it promised to be. But noon this day brought him home.

"Happy New Year!" he cried happily, although it was still December thirty-first. "Looky what your husband brung you! Ain't he nice boy?"

Jess opened the parcel and saw the wrist watch, and she gave him a kiss for each hour on the dial.

"But, Joe! How could you do it? How could you ever afford such a darling thing?"

"The old red line on the chart is going to show a new peak," he declared. "Old Rotherwell is going to give Wilshire's Colony current; his men are out there now setting poles."

"How lovely for Kay! She just told me," Jess said. "But I think she's gone crazy with joy, Joe. She called up to invite us out tonight and she thanked me for that copper tray, and she said the queerest things. She said that as soon as she got it she rushed right to Mr. Rotherwell and just made him promise to give the Colony electricity. Did you ever hear of anything so --"

"I've got to confess," Joe said, but not very humbly. "I -- that tray is down at the shop, Jess. I thought Kay deserved something better from you, so I sent her something a little better."

"Why, the very idea!" Jess exclaimed. "That was a lovely tray. But what on earth did you send her?"

"Well, so to speak," said Joe grinning. "I sent her phonograph records."

"For the land's sakes! Phonograph records!"

"So to speak," said Joe. "I learned about women from you, woman! I sent her a toaster -- an electric toaster that toasts the toast and pushes it up out of the heat the instant that it is."

"But Kay had no electricity --"

"That's what I thought," said Joe, with one of his grins. "And you didn't have a phonograph. But you have one now. And Kay has a grandfather. And she had a brand new shiny electric toaster. I thought she'd do some tall coaxing with that grandfather of hers. And I figure that my sales of lamps in the Colony next year will be --"

"Why, Joe Carsey," exclaimed Jess, but not with much more venom than there is in a violet, "I think you're terrible! Why, you're a -- a regular tempter."

"So," said Joe Carsey cheerfully, "is your Aunt Ella."