from McClure's Magazine

Billy Brad and the Forbidden Fruit

by Ellis Parker Butler

"And you must not take an apple," said Billy Brad's mother warningly. "If you want an apple, come to me and ask me, and if I think you may have one I will pare one for you. You are too young to know whether you need an apple or not. Do you understand? You must not take the apples!"

"Yes, mama," said Billy Brad cheerfully, and that was a bad sign. There was no reason why Billy Brad should be cheerful; for the day, so far, had not been a success -- success and mischief being synonymous in Billy Brad's mind. So far, he had been spanked only twice, and this was far below the average and indicated an unsuccessful day. His world seemed barren of opportunities.

The day had begun well enough, for he had found a large jar of cold cream on his mother's toilet-table, and had oiled the bedroom floor with it, giving the floor a better gloss than even Katy had ever been able to give it. For this he had been mildly spanked. Then he had found the shears, and stood on tiptoe, searching the top of Mrs. Bradley's toilet-table for a certain long switch of hair that at times reposed there -- for at that moment Billy Brad was a barber, and wanted to "cut it." There was no switch visible, so he "cut" the hair of Mrs. Bradley's best silver-backed hairbrush. The crisp bristles snipped deliciously, but the affair was a tactical error.

The day had begun well enough, for he had found a large jar of cold cream on his mother's toilet-table, and had oiled the bedroom floor with it, giving the floor a better gloss than even Katy had ever been able to give it. For this he had been mildly spanked. Then he had found the shears, and stood on tiptoe, searching the top of Mrs. Bradley's toilet-table for a certain long switch of hair that at times reposed there -- for at that moment Billy Brad was a barber, and wanted to "cut it." There was no switch visible, so he "cut" the hair of Mrs. Bradley's best silver-backed hairbrush. The crisp bristles snipped deliciously, but the affair was a tactical error.

"Just look at that brush!" his mother had exclaimed. "It is not good for a thing in this world, now, but to spank you with. I'll keep it to spank you with, Billy Brad. Come here to me!"

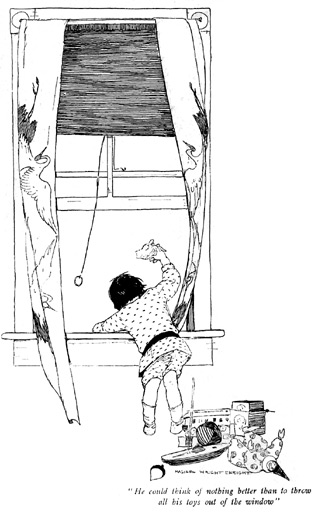

For an hour after that Billy Brad's morning was dull. He could think of nothing better than to throw all his toys out of the playroom window into the geranium-bed -- killing "Inyuns"; but when all the red-blossomed Indians had been crushed to earth, this was no fun, and he came downstairs. His first impulse was to come downstairs as a "big old dog" -- on his hands and knees; but he remembered that the last big old dog he had been had fallen bumpety-bump down the entire long flight, so he came down as a big old snake.

A big old snake comes downstairs head first, on its belly, clinging with its toes, and hissing virulently. Four or five steps from the bottom, it loses its hold and bumps down. In this it resembles the big old dog.

Billy Brad picked himself up and seated himself on the bottom step. The descent had been a failure; he was not even hurt. It was evident that the world was askew this morning, and Billy Brad had about decided to be gloomy, when he thought of the apples.

The apples were in the lower part of the sideboard -- the part with doors. There were bottles of catsup and Worcestershire and cans of maple syrup in the lower part of the sideboard, and when Billy Brad opened the door of the lower part of the sideboard he saw a catsup bottle. Here was something worthwhile! The things Billy Brad might do with half a bottle of catsup would make the stoutest heart tremble. In your wildest imaginings you could not guess what Billy Brad could do with half a bottle of catsup. He would not paint the wallpaper with it, for that is something you could imagine him doing. Billy Brad always did the thing no one else could possibly have thought of doing. But just as he reached for the catsup bottle Mrs. Bradley entered from the kitchen.

"Billy Brad!" she said sharply. "Don't you touch those apples."

"No, mama," he said sweetly, as she closed the door of the sideboard.

"Now, mind!" said his mother. "Will you promise me not to take an apple?"

"Yes, mama," said Billy Brad. "I won't take a napple, but -- but -- but maybe a big old slickery snake might take a napple."

Mrs. Bradley looked at him suspiciously. She knew that Billy Brad could, with ease, transform himself into beast or bird or reptile. When he crept on his hands and knees and said, "Wow, wow!" he was a big old dog; when he walked on hands and feet, with his plump little haunches higher than his head, and said, "Oof, oof!" he was a big old bear; and when he lay flat on his belly, and wiggled and hissed, drawing himself along by his elbows and fingernails, he was a big old slickery snake. A slickery snake might do, with a clear conscience, things Billy Brad had promised not to do.

"Billy Brad," said his mother, "you must promise that no big old slickery snake, nor any other animal, or bird, or anything else, will touch the apples. Will you promise?"

"Yes, mama," said Billy Brad cheerfully. "And -- and -- and if a big old slickery snake comes to take one of my mama's apples, I'll take a big swo-word and -- and -- and cut its head off, I will!"

"Never mind about that!" said Mrs. Bradley. "You have promised. My little boy would not tell a fib. I can trust him. Can't I?"

"Yes, mama," said Billy Brad willingly, for he had no intention of taking an apple. He desired a catsup bottle. He hungered for a catsup bottle. What he would do with it when he got it did not bother him at all. A catsup bottle half full of catsup is a useful thing for a boy to have on hand in case of emergencies. There is no telling when it may come in handiest, and the rational thing to do, when there is a catsup bottle to be had, is to have it.

Mrs. Bradley went into the kitchen, her mind at rest as to the apples, for Billy Brad was a truthful boy. If he said he would not take an. apple she felt she could depend on him not to take one, for he had been taught the awfulness of a lie.

Mr. Bradley had taught him, with a little rawhide whip that lay on the top shelf of the hall closet. Billy Brad knew that a lie was the one unforgivable sin.

Mr. Bradley had taught him, with a little rawhide whip that lay on the top shelf of the hall closet. Billy Brad knew that a lie was the one unforgivable sin.

Billy Brad lingered between the dining table and the sideboard when his mother had gone into the kitchen. Although nothing had been said about catsup bottles, he had a feeling that he had better wait a while before taking one. He leaned against the dining table and waited. It was a circular table, of mahogany, with a high, glowing polish, and when Billy Brad leaned against it with his head raised enough to give him a good view of its top, his mouth just reached the rim of the table. He put out his tongue and tasted the tabletop. There was no taste to it at all; it was neither sweet nor sour nor bitter. He opened his mouth wider and tried to bite the table top, and his sharp little teeth sank into the soft, varnished wood quite pleasantly, and when he looked he saw that his teeth had made a pretty semicircle of white dots. This was interesting. Billy Brad moved slowly around the table, making semicircles of white dots. He felt that the appearance of the table was greatly improved. He made dots quite around the tabletop.

On the top of the table was a large, highly embroidered linen table cover, and in the exact center of the cover stood a tall glass vase of flowers. Billy Brad fingered the edge of the table cover, and it moved. He grasped one of the pointed scallops and walked slowly around the table. The entire table cover revolved, and with it the vase in the center turned slowly. As he walked he kept his eyes on the vase, and sang:

"All aroun' a mubbery-bush, mubbery-bush, mubbery-bush;

All aroun' a mubbery-bush, mubbery-bush, mubbery-bush."

He walked around the table three times, sing-songing, but the vase did not topple over. It was an unsatisfactory vase, and the fourth time around Billy Brad held out his free hand. By stretching out his free arm he could touch three chairs as he passed them. So he sang:

"All aroun' a mubbery-bush -- tag!

Mubbery-bush -- tag!

Mubbery-bush -- tag!"

On the fifth round, holding his hand extended after touching the second chair, his fingertips touched the door of the sideboard. It was a loosely hung door, and, when he touched it, it closed and rebounded open again. On the next round he tagged it a little harder, and it opened a full two inches. A delicious odor of apples issued forth, and through the crack Billy Brad could see the catsup bottle. When he reached the door again he deserted the table cover and opened the sideboard door. He put his hand into the lower part of the sideboard, reaching for the catsup bottle, and the topmost apple of the pile in the dish bumped to the floor and rolled under the table. Billy Brad withdrew his hand quickly, and three more big red apples followed and rolled across the floor. A glimmering of the power of circumstantial evidence to convict the innocent frightened him, and he hippety-hopped guiltily twice, away from the sideboard.

He went into the hall. When apples are rolling is no time to acquire a catsup bottle. The front door was open, and Billy Brad went out upon the porch. At the bottom of the porch steps was a cement walk, and at the corner of the walk was a small hole, no bigger than his thumb, that led into unknown depths under the walk. Billy Brad remembered this hole now, and he remembered that he had a dead caterpillar in the porch hammock, so he got the dead caterpillar and put it in the hole. He now had three dead bugs, a glass marble, and a dead caterpillar in the hole. It was quite a treasure-trove. He looked about for some other thing of great value to put in the hole. He tried to remember where he had seen a certain dried angleworm. He heard the screen door of the next house slam. He brightened at once. It meant that Florence was coming out to play.

Florence came down her porch steps slowly, with her hands behind her back. She looked at Billy Brad doubtfully, for only last night she had been whipped for letting Billy Brad put burs in her hair. She had gone in proudly, with her yellow curls beautifully "done up" in the back with burs, and instead of meeting with praise she had been whipped. Contact with Billy Brad might mean serious catastrophe. She hesitated at the bottom of her steps.

But Billy Brad did not hesitate. He walked straight across the pansy bed into Florence's yard, and took his place immediately before her, with his hands behind his back, -- because Florence had her hands behind her back, -- and looked at her.

"I got some'n an' you ain' got," said Florence teasingly.

"I got a -- a big old lion in my house," said Billy Brad. "And -- and -- and I got it down my cellar. And -- and -- and I got it in a coal-bim, I have. And -- and -- and if I want to I can go down in my cellar, and -- and I can go in my coal-bim. And -- and I can pat my big old lion, I can. And -- and he won't bite me, for 'cause I tooked my mama's scissors and I cutted his teef all out."

Florence looked at him doubtfully. To her mind, it was quite within possibility that a boy should have a lion down cellar in his coal-bin. If he had, it was quite useless to compete by mentioning that her mama had a big cake in the kitchen. She decided it would be more tantalizing to stick to things near at hand.

"I got a napple," she said, suddenly flashing it before Billy Brad's eyes, "an" you ain't!"

"That's my napple!" said Billy Brad promptly. "I want my napple."

"It's my napple!" said Florence. "My mama gave me my napple."

"I want it," said Billy Brad, and he took it. At that age all little boys are robber barons, and no little girls have sex, so he took it as a right. Florence, being robbed, opened her mouth and wept. Billy Brad stood ungallantly and watched her cry, for the cryings of Florence were an interesting mystery to Billy Brad. She was the best cryer on the block, and when she cried Billy Brad could see all the trimmings of the inside of her mouth -- the small white teeth, the funny crinkles in the roof of the mouth, and the red tongue all the way back to where it was hitched on. It was an interesting spectacle, and Billy Brad took a step nearer, that he might see better.

"My papa's got gold teef," he said, when he had satisfied himself there was no chance of seeing all the way down Florence's throat. "And you ain't got gold teef."

Florence stopped crying immediately. She had never thought of having gold teeth. It was a new idea. She considered it a moment, and decided that the loss of the apple was the most important incident of the moment.

"I want my napple!" she screamed. It was a shocking display of temper.

"You can't have it," said Billy Brad, and turned away. "I need it."

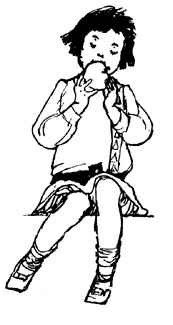

Five minutes later Billy Brad sat on his porch steps, eating the big red apple, and Florence, virtuously aloof, sat on her own steps, eating another, when Mrs. Bradley, passing through the dining room, saw the apples on the floor and the sideboard door wide open. She stepped to the front door and looked out. Billy Brad, who had promised not to touch the apples, eating one! As he heard his mother's step he looked up at her -- placidly.

"Billy Brad," said his mother sternly, "I am going to tell your father!"

"Are you?" said Billy Brad pleasantly. He did not ask what she was going to tell him. He did not so much as wonder what. So many things happen in the course of a day that it is not worthwhile trying to think what a father is to be told. Often, when Billy Brad had decided what he was to be whipped for, it had, in the event, proved to be something entirely different -- something he had quite forgotten.

"And I shall see that he gives you the good whipping you deserve!" said Mrs. Bradley severely.

Billy Brad dug his sharp teeth into the apple. On the score of the apple his mind was at rest. There, at least, he was guiltless. It was his by right of conquest. He humped his back a little more, as if in mute admission of the truth of the sentiment, "We are all miserable sinners."

He ate the apple to the utmost core, and put the core down the hole with the caterpillar. Not because the core was precious, but because it seemed a logical thing to put an apple core down a hole so evidently sized to receive it.

"Now, Billy Brad," said his father, that evening after dinner, "I want a little serious talk with you, young man! Your mother told you not to take an apple today, and you promised not to take one. Do you remember that?"

"Yes," said Billy Brad; "and -- and -- and Flowence had a napple, and -- and --"

"Now, never mind about Florence," said Mr. Bradley coldly. "You promised mother not to take an apple; and when a boy promises not to take one, and then does take one, it is a fib, and a fib is a lie. Do you understand?"

"Yes," said Billy Brad. "Papa, fen -- fen -- fen you open your mouf I can see all your gold teef. And -- and -- and Flowence ain't got any gold teef!"

He said it sadly, as if not having gold teeth was the ultimate sorrow. This was, as you can see at once, a complete explanation of the apple episode, and his father should have known it. If Florence had no gold teeth Billy Brad must have been looking into her mouth, and if he had looked into her mouth she must have been crying, and if she had been crying it must have been because Billy Brad took her apple, and that explained where Billy Brad had obtained the apple. But fathers are notoriously dense.

"We'll forget about gold teeth," said Mr. Bradley coldly. "We will talk about apples. Now, Billy Brad, I want you to tell me the whole apple story."

Billy Brad brightened. He loved stories. He loved to hear them, but even more he loved to tell them.

"There was a big old slickery snake," said Billy Brad, "a great big old slickery snake, and -- and -- and it wuggled like a wum --"

"Stop there!" said his father. "It did not wiggle like a worm, for there was no snake -- no snake at all."

"And -- and -- and there wasn't no big old slickery snake," said Billy Brad, "and it didn't not waggle like a wum -- What did it wuggle like, papa?"

"It didn't wiggle like anything," said Mr. Bradley sternly, "There was no snake, and you know it. Now, go on with this apple story. Your mother told you not to take an apple --"

"Yes," said Billy Brad, "and -- and -- and -Why wasn't there no wuggly old snake, papa?"

"Because," said Mr. Bradley, "you were the snake."

"And I was the old slickery snake," said Billy Brad. "And -- and -- and I wented into the garden, and -- and I wuggled up a noak tree --"

"Now, stop!" said Mr. Bradley. "That's nonsense. You didn't go into the garden, and you didn't wiggle up an oak tree, because there is no oak tree in the garden, and if there was it wouldn't have anything to do with apples. Apples don't grow on oak trees. Apples grow on apple trees. Acorns grow on oak trees. And these apples were in the sideboard."

"Were they?" asked Billy Brad, with surprise.

"Of course they were!" said Mrs. Bradley impatiently. "You know they were, Billy Brad."

"Do I?" said Billy Brad, but the information seemed new to him. "And -- and -- and," he began carefully, "there wasn't no old wuggly snake, and there wasn't no napples on the noak tree, for 'cause napples grow on napple trees. And -- and -- and -- " He hesitated. Nothing in the way of a story seemed to suit his father this evening. He felt he must be careful. "And a big old nangel flewed down," he began briskly.

"No," said his father, shaking his head. "No angel flew down. Not an angel. Not a single, solitary angel. You took the apple, Billy Brad!"

"Out from the sideboard in the garden?" asked Billy Brad.

"The sideboard couldn't be in the garden," said Mr. Bradley, "and you know it. Sideboards are never in the garden. Sideboards are in the dining room. You went into the dining room, and you took an apple out of the sideboard. No snake, no oak tree, no garden. You took the apple. Now, why did you take the apple?"

"For 'cause," said Billy Brad, turning his bright eyes up to his father's face, "for 'cause I was a devil!"

That settled it! A father, even an indulgent father like William Bradley, cannot have a son saying such things. He may, or he may not, believe in the black personage mentioned himself, but he can not permit a boy who has stolen an apple, and then fibbed about it, to throw the blame on Satan, still less mention his name in its vulgar form in excuse of his misdoings. He led Billy Brad through the hall to the kitchen, stopping at the hall closet for the rawhide whip. The interview in the kitchen was long. There had to be a long explanation of the reason for the whipping before it took place, and a long wiping of tears and close clasping of a sobbing little boy in a father's arms after it was all over. Put Billy Brad never bore ill will. He kissed William Bradley fervently when it was all over, and took his hand to be led back into the parlor.

Mrs. Bradley was not alone. She was sitting very primly in her chair. And facing her in another chair was Mrs. Wix, her lips set firmly. You know the unpleasant half hour when the woman next door comes to complain of your child, and how unpleasant it is when you know she is right. You know in your heart she is right, and yet you feel that she is a most disagreeable, meddling person. Your back stiffens at once. Mrs. Bradley's back was as stiff as a ramrod.

"More of Billy Brad's naughtiness!" she said.

"That's bad!" said Mr. Bradley, without vigor. He knew one thing. After the painful scene in the kitchen, Billy Brad would receive no more punishment at his hands that evening!

He took Billy Brad on his lap. "What's the young terror been doing now?" he asked.

"Will you tell him, Mrs. Wix?" asked Mrs. Bradley stiffly.

"I prefer you should tell his father," said Mrs. Wix, with the air of a woman who has seen her unpleasant duty and has done it.

"Very well," said Mrs. Bradley. "This morning Mrs. Wix gave Florence an apple and sent her into the front yard. She heard Florence cry, and looked out in time to see Billy Brad deliberately take the apple away from her, and then he stood and made faces at her while she cried!"

"I -- I -- I saw how many teefs Flowence has got," said Billy Brad. "But Flowence hasn't got any gold teef. My papa's got gold teef."

The information was for the benefit of Mrs. Wix, who did not seem much impressed by it, after all.

"Took her apple, did he?" said Mr. Bradley. "Well, I hope he gave it back."

"He did not," said Mrs. Wix. "He took it away from her, and let her come crying to me for another while he sat on his step and ate it. I would have come over then but I saw Mrs. Bradley come out. I supposed, naturally, she meant to punish him; but as I heard nothing of the matter from her, I thought it my duty --"

"Quite right!" said Mr. Bradley genially.

"Because I thought Mrs. Bradley might think your son had got the apple in his own house," said Mrs. Wix.

Mr. Bradley looked at Mrs. Bradley meaningly, and Mrs. Bradley arose.

"We shall see that it does not happen again," she said, leading the way to the door. "Mr. Wix is well, I hope? Good night."

"Well?" she said, when she reentered the parlor. "So that is where Billy Brad got the apple! He did not steal it, after all. He did not tell me a fib. And the poor child had to be whipped!"

"Yes," said Mr. Bradley gently. "But why didn't you tell us where you got the apple, Billy Brad?"

It was evident that Mr. Bradley did not consider infantile highway robbery a serious crime -- at least, not at all as serious as lying.

"Why didn't you tell us about the apple in the first place?" asked Mr. Bradley. "I asked you to tell me. Tell papa now just as it was, Billy Brad."

"There was a old noak tree," said Billy Brad eagerly, "and -- and -- and napples growed on it, and -- and -- and a slickery old snake wuggled up the big old noak tree, and -- and -- and it looked a napple --"

"Careful!" warned Mr. Bradley.

"And -- and -- and the slickery old snake wuggled down the noak tree," said Billy Brad, very carefully and very slowly, "and -- and -- and a big old nangel flewed down, and -- and -- and --"

Mrs. Bradley opened her lips to speak but Mr. Bradley motioned her to be silent.

"And -- and -- and the big old slickery snake gived her the apple, and -- and -- and the nangel he tooked his swo-word, and he said, 'Get out of my garden!' and -- and -- and --"

"For mercy's sake! You poor kiddie!" exclaimed Mr. Bradley, hugging the wee boy tight in his arms. "You poor kiddie! I told him to tell me the story of the apple, and he's been trying to tell me the story of the Garden of Eden!"

"And -- and -- and there wasn't no old sideboard out in the garden," said Billy Brad, with bravado.

"No, siree, Billy Brad!" said Mr. Bradley. "You knew better than papa that time, didn't you? And I whipped you for telling a fib, when you didn't tell one. So you can have whatever you want, Billy Brad, to square us. Now, think! What do you want most of anything, Billy Brad?"

"Gold teef," said Billy Brad, without the slightest hesitation.