from Every Week

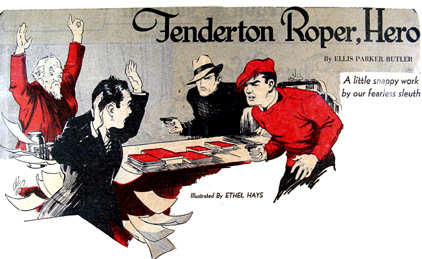

Fenderton Roper, Hero

by Ellis Parker Butler

When Fenderton Roper's left front tire blew out just as he was leaving his father's driveway in his snappy little roadster Fenderton said "Pshaw!" but what he felt was worse than that.

He was on his way to pick up pretty May Middleton and take her to the movies. He had a whole dollar in his pocket and three gallons of gas in the car's tank, but the tire was utterly beyond repair, and to get money quickly for a new tire was about as impossible as to buy the moon.

Fenderton's father was mad at him and his mother had been forbidden to give him any money; his father declared it was certainly time that Fenderton got a job and showed if he was good for anything at all.

With another "Pshaw!" Fenderton got out of the car and pushed it to one side. He took his cane from the seat -- for he never went forth without that insignia of manly dignity -- set his natty hat at the proper jaunty angle, and set forth for May Middleton's humble home on foot.

"Why, Fenderton," May said when she had issued from her rather humble door, "I thought you were coming in your car. You said you were coming in your car, Fenderton."

"I believe I did express that intention," Fenderton said in his haughtiest manner, "but I presumed you would rather have me get here on time than to waste a lot of time changing a tire, and not get here on time."

"Why, of course, Fenderton," said May, falling into step with him. "Did you have a blow-out?"

"I should think you would presume that I did have a blow-out when I talk about changing tires. Miss Middleton," Fenderton answered. "I should think that by this time you ought to know me well enough to know that."

"Well, you needn't be so cross about it, Fenderton," said May in her usual cheerful way. "I only asked you. I like that hat, Fenderton; you look swell in that hat."

Thus mollified, Fenderton condescended to converse in a more friendly manner, and his self-esteem was quite restored by the time they reached Main Street. Here, on a door beside a butcher's shop, the lettering "Robert Connerty, Private Investigator," caught Fenderton's eye, reminding him that he had a somewhat one-sided arrangement with that local detective.

"Wait a minute here, May," he said. "I've got to run up and see the Big Noise a minute. Report, you know."

"Why, Fenderton, I didn't know you were still doing detective work," said May. "You haven't said anything about it for a long time. I guess you can keep things pretty dark when you want to, can't you, Fenderton?"

"In the detective line a man has to," said Fenderton. "An undercover man has to keep it pretty quiet. May," and with that he opened the door and went up the dirty stairs.

Robert Connerty was asleep with his feet on his desk, but he looked up as Fenderton entered.

"For shoutin' out loud!" he exclaimed disgustedly. "You here again? Talk about pests!"

"I just dropped up to see if there were any cases --" Fenderton began, but Connerty silenced him.

"Listen, bo," he said roughly, "I'm a busy man, see? I can't have all you dumb bunnies buttin' in on me all the time. I told you what you could do -- you find a case and come and tell me, and I'll see will I let you work on it. You dug up a case?"

"Well, not yet, Mr. Connerty."

"Then you get out and stay out until you do, see?" said the detective, and put his feet on the desk again and closed his eyes.

"What did he say, Fenderton?" asked May when Fenderton was at her side again. "Was your report all right?"

"You'll have to excuse me from talking about that at the present time," Fenderton told her. "This is a pretty big affair I'm working on just now, and the least said the soonest mended. I mean. May, you wouldn't talk or anything like that, but I guess it would be a pretty mean piece of business if something got out just when we were ready to snap the old bracelets on a couple of crooks that --"

He paused an instant then, but only an instant. His attention had been caught by a card standing in the corner of a small stationery and cigar shop. This sign, roughly scrawled on the bottom torn from a cardboard box said "Boy Wanted."

Fenderton was far from being a mere boy. A man who has been to college -- and Fenderton had been kicked out of three colleges -- and who carries a cane, should be justified in considering himself a man, but with his father in the mood that he was, money was very scarce with Fenderton.

In the instant that he hesitated in his words to May Middleton, Fenderton had thought "There's a job," and had, in his expansive way, vindicated to himself its acceptance -- if he could get it.

"If I accept that job," he said to himself, "I'll work in and own the dinky place, and rent a store, and have 60, 100, a thousand chain stationery stores --" and that was as far as he had got when May spoke.

"But of course I wouldn't tell, Fenderton," she said. "Not that I want to know anything about your detective work, Fenderton; not until it's all finished. You'll tell me then, won't you, Fenderton? Because I'd be awfully glad to know then."

In confidence it may be said that May Middleton did not take Fenderton's talk about his detective work very seriously -- not seriously at all.

She was well aware that Fenderton was apt to ride a very high horse at times, and that he liked almost too well to seem impressive, and particularly to impress May Middleton with his importance. Young men who like young women especially well are apt to want to impress them, however, and May Middleton knew that Fenderton was what she would have called a nice boy. She liked him very much indeed, and she knew he would get over his habit of exaggeration when he was just a little older.

The picture they were seeing at the talkie theater was only fair to middling, but it was not as dull as it might have been and May Middleton was giving it her entire attention when two men a few seats forward got up and went out. They were young men and wore sweaters instead of coats, and they had probably seen the last half of the picture and did not care to see it again. Fenderton got up also, and leaned over confidentially.

"May," he whispered, "keep my hat and cane. Don't look around when I go out. I'll be back. Those two fellows -- I want a look at them."

Fenderton went up the aisle and out into the lobby and to the street. The two young men in sweaters were already on the street but Fenderton did not give them so much at a glance. He turned in the opposite direction and hurried to the little stationery store. The "Boy Wanted" sign was still in the window and Fenderton went into the little shop.

Behind the counter was a woman almost too fat for the narrow space between it and the shelves on the wall. She was waiting on a small boy who wanted a five-cent tablet of school paper and he was having trouble in deciding between two or three kinds.

"Choost a minute, mister," she said to Fenderton; and to the boy, "You take this one, yes? Nice picture on it; plenty paper in it." The boy took the tablet and gave his money, and the woman turned to Fenderton. "You want, mister?" she asked.

"You've got a sign in the window," Fenderton said. "You want a boy?"

"Boy?" she said, eyeing Fenderton with surprise. "You know a boy what wants a job, yes?"

"I want a job," said Fenderton almost desperately. "I've got to have a job, do you see? I guess you can understand that I wouldn't take a job like this unless it was a pretty serious matter with me. I wouldn't take it if it wasn't for circumstances."

"Succumstances?" said the woman. "You got succumstances?"

"Reasons," explained Fenderton, mustering his patience.

"Oh, reasons!" said the woman, nodding her head. "You got reasons you want a job. Plendy peoples got reasons they wants jobs these days. Choost wait a minute."

Her reason for asking Fenderton to wait a minute was a customer who entered the store. He was an elderly man and he came to the counter where Fenderton stood. He smiled at the shopkeeper but he said not a word. Mrs. Gruber turned and opened the wall case behind her and took down a tin of Golden Glow, smoking tobacco. Without a word the man laid 15 cents on the counter, and took his tin of tobacco and went out.

"Dumb," said Mrs. Gruber. "And deef, poor feller. Mr. Blatz, from across the street upstairs. Effery day he comes by the store and a tin of Golden Glow buys. Sometimes a paper, yes, or a magazine not so often. Ain't it a shame?"

"Yes," said Fenderton. "And about the job, now --"

"I don't know hardly," said Mrs. Gruber. "You was plenty big for a boy; we ain't got much room for two such big ones. Well, maybe. We don't could pay so much."

"What is the remuneration?" Fenderton asked.

"Remuneration? You mean how long you work, maybe?"

"The pay," Fenderton explained. "How much do you pay?"

"Eight dollars is all. For a week we pay eight dollars. Only Sunday we stay shut."

"I'll take eight dollars," said Fenderton.

"Well, I guess maybe we try you awhile anyway," said Mrs. Gruber. "Maybe you don't fool around so much like a little kid. And anyway maybe the job don't last so long; my husband he got sick and has to go by the country; maybe when he comes back he don't want no boy."

That suited Fenderton well enough. "When do you want me to start to work?" he asked, and it was arranged that he begin the next morning, and he hurried back to the theater.

"Did you sleuth them, Fenderton?" May asked in a whisper. "Did you detect them?"

"Sh!" Fenderton shushed. "Keep it dark, can't you? This is a big case. May -- a mighty big case. Undercover stuff. I won't be seeing you much for a couple of weeks, I guess; I've got to lay low and pretend like I'm just a dumb-bunny in a shop, maybe. Throw the crooks off the track, see?"

"Why, of course, Fenderton," said May, although what she saw was that Fenderton had probably found another job that was so petty he was ashamed of it.

The next morning at 8 o'clock Fenderton was on hand at the Gruber stationery store, and he found that his duties were such that he could easily handle them. Mr. Gruber before he had left marked everything in plain figures for his wife's benefit, and when he needed to know anything Mrs. Gruber was there to be asked. He found, too, that he was most needed to take care of the shop when Mrs. Gruber made a hurried trip to her flat upstairs, where she had three small children.

It was about the middle of the afternoon that Mrs. Gruber had to go upstairs to attend to her children. She took all the money except change for a dollar out of the cash register and put it in a small canvas bag and put the bag in the bosom of her dress.

"I don't be so long," she told Fenderton. Right away down I come as quick as I could. You get along all right, I guess, yes?"

The sun was shining in brightly over the wooden screen that backed the show window and Fenderton leaned back against the shelf behind the counter, and the door opened and Mr. Blatz came in. He came to the counter and pointed at the tins of Golden Glow in the wall-case and held up one finger.

"Yes, sir," said Fenderton briskly. "One Golden Glow, 15 cents," although Mr. Blatz could not hear him, being deaf and dumb, and Mr. Blatz took the tin and laid down his money, and smiled in friendly fashion. The store door opened and two men came in. Automatics flashed from their pockets and the muzzles covered Fenderton and Mr. Blatz.

"Hands up!" ordered the tougher of the two, and Fenderton and Mr, Blatz quickly raised their hands high above their heads. "Shut up and keep shut up or you'll get yours and plenty."

"I got 'em, Joe," said the other man. "Get busy."

Joe walked around behind the counter and opened the cash register and uttered an oath of disgust as he saw the few nickels and dimes there. He turned to Fenderton.

"You don't get away with this, bo," he said. "Where's the rest of the cash? Come across."

"That's all there is," said Fenderton. "That's all Mrs. Gruber left here. She took the rest with her."

"Cut it!" growled Joe. "Where's the cash? Come across. Talk fast."

"My goodness!" said Fenderton. "I am telling you the truth."

His attention was all given to Joe and the ugly automatic, and Joe's companion, with his gun pointed at Mr. Blatz, was scowling at Fenderton. Mr. Blatz, with his hands held high, did not move.

He knew that his wife, upstairs across the street, always watched him until he was safely home, afraid that some car he could not hear might strike him as he crossed the street. He could see, over the window screen, that she was watching him now, and his fingers were busy forming letters of the deaf-and-dumb alphabet.

"Hold-up men here," he spelled; "Telephone police," and he spelled it over and over again while Fenderton talked, trying to convince Joe that he was telling the truth about the money. In the window across the street Mrs. Blatz read her husband's message and ran to the telephone.

"Listen, bo," snarled Joe, "you've got one more chance, see? Where's the cash?"

"But I'm telling you that there isn't any more here," said Fenderton. "I'd --"

A police car swung to the curb and two burly policemen leaped from it. Their automatics were in their hands and they threw open the door. Joe and his companion gave one look and their hands went up and their guns fell to the floor.

It was 10 o'clock the next evening before Fenderton was able to see May Middleton, but she came out to meet him as soon as she heard his whistle, and she had read the news in the evening paper. The paragraph said:

"Joseph Gulkin and Richard Cuffy, two holdup men for whom the police squads have been hunting, were captured yesterday afternoon while holding up the Gruber stationery store, 857 Main street. Credit for their capture is given to Fennerton Rober, who kept the two men in conversation until the arrival of officers Murphy and Hargraves in police car No. 45."

"Why, Fenderton," exclaimed May Middleton as she took his arm and fell into step with him. "You were in earnest, weren't you?"

"I don't know what you mean. May Middleton," said Fenderton severely. "I hope you don't presume to say you think I've been kidding you."

"Of course not, Fenderton. But -- well -- you were detecting, weren't you? And you did capture those holdup men, didn't you?"

"Oh, that!" said Fenderton loftily. "That's all in the day's work of a detective."

"Yes, I know," said May Middleton. "But I do think it was awfully smart of you, Fenderton. Why, Fenderton, you're a hero."

Fenderton lighted a cigarette and snapped the match away from him carelessly.

"All in the day's work, May; all in a day's work," he said. "And am I sore?"

"Sore?" asked May. "What are you sore about?"

"They spelled my name wrong," said Fenderton, but he laughed. "But that's life," he said; "that's life."