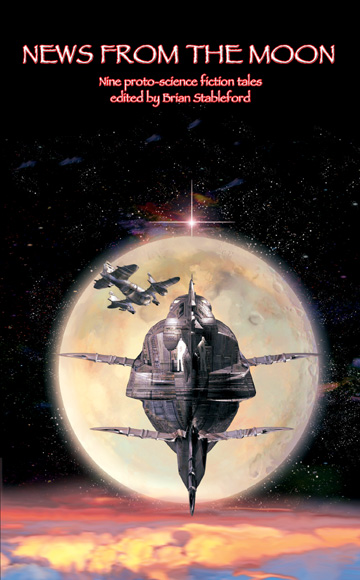

Review by Glenn Russell

We come to understand French

speculative fiction is a distinct tradition, January 21, 2014

After centuries dominated by

the church and after the 18th century’s age of reason, there was

an explosion of imagination in the 19th century. From the romanticism

of poets and painters such as Byron, Keats, Delacroix and Turner to the

philosophy of such visionary thinkers as Hegel, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard

and Nietzsche, from Darwinian evolution, Marxist economics, Freudian psychoanalysis

to the astonishing new scientific and technological discoveries, human

nature, history, society and the universe came to be seen in unique, fresh

and sometimes disturbing ways.

Brian Stableford’s 14

page introduction provides the historical and literary context for the

9 French proto-science fiction stories in this collection, including how

the French writers have the longest standing history of speculative fiction

based whole or in part on scientific ideas. Among the better known authors

examined within the world of French literary-scientific fiction are Jules

Verne and Théophile Gautier and Victor Hugo. We come to understand

French speculative fiction is a distinct tradition not to be limited or

confused with what we traditionally think of as science fiction. Here

is a brief review of 5 of the 9 tales:

News from the Moon –

Louis-Sebastien Mercier

Although written in 1768, the spirit of this tale is very much part of

19th century romanticism beginning with the first sentence: “The

account I am writing is perfectly true, although the reader might deem

me a madman.” A truly remarkable account – communicating with

a departed friend living in more rarefied form and answering questions

from his position on the moon. By way of example, here is what his friend

has to say, “Science, uncertain on Earth, is supported here by the

clearest evidence. There is no object that our eyes cannot easily penetrate

. . . “. Ah, proto-science fiction! A man living in a form beyond

the grave underscores how his experience is supported by the evidence

of science.

The Future Phenomenon –

Stéphane Mallarmé

With uncanny and almost eerie foresight, Mallarmé anticipates the

genre of post-nuclear war fiction with this short-short story. The symbolist

poet/author pens how in some barren, dusty, earth-scorched future husbands

and their bald, ghastly-looking wives enter a tent erected by the 'Showman

of Past Things' to see a display of a beautiful naked women with a full

head of blond hair. “When all have contemplated the novel creature,

a relic of some earlier accursed age – some indifferently, for they

will not have the power of understanding, but others heart-broken, their

eyelids moist with tears of resignation – they will look at one another.”

”Mallarmé invites us to reflect on what life would be like

in a future completely devoid of beauty.

The Metaphysical Machine

– Jean Richepin

Instead of an inquisitive English scientist exploring the future as we

find in H.G. Well’s ‘The Time Machine’, Richepin’s

short tale features an obsessed French madman exploring metaphysical truth

by a machine that looks something like the Englishman’s time machine

but with two important differences: a dentist’s drill rigged up to

produce excruciating pain in his hollow tooth and a mechanized scroll

enabling the Frenchman to write as he undergoes his torment. Sounds crazy?

It is crazy, although the narrator repeatedly insists he is not mad. At

one point in his frenzied telling, our philosophical pioneer exclaims,

“Besides the external senses and the internal senses, there is another

sense, internal and external at the same time, knowing its object as the

external senses do, immaterial as the internal senses are, but having

absolutely nothing in common with either of them – and that is the

SENSE OF THE ABSOLUTE.” Now, where does all this lead us? Does the

French visionary survive his adventure as does Well’s English scientist?

Let me just say this tale is taken from a collection of Jean Richepin

stories entitled ‘Moris bizarres’ (Bizarre Deaths).

The Monkey King – Albert

Robida

A tour de force of imagination, this rollicking 130 page adventure tale

has our hero lost at sea as an infant before being washed ashore on an

island where he is then raised by a community of warmhearted and wise

apes. There are all sorts of fabulous happenings when the hero moves back

to the world of men and eventually becomes a courageous and creative ship

captain. Here is an example of the dozens of adventures, when the hero,

Saturnin Farandoul by name, and his companion, wear diving gear and explores

the ocean: “Armed to the teeth with hatchets in hand and two pistols

operated by compressed air in their belts, along with sharp knives, the

mariners threw themselves upon the slimy rocks and ventured into caverns

inhabited by monsters unknown to man, which only the most deranged imagination

could have dreamed up: six-meter-long lobsters, sea-crocodiles, torpedo-squids,

crabs with a thousand feet, sea serpents, finned elephants, giant oysters

and so on.” Albert Robita’s tale is not only sheer adventure

in the tradition of Odysseus and Sindbad but prompts us to reflect on

our human interaction with the planet and other species.

Martian Mankind – Guy

de Maupassant

A pint-sized, bespectacled mousy visitor enters the study of the gentlemanly

narrator and excitedly discloses many scientific facts about the planet

Mars and mixes in details of the appearance and movements of the Martians,

all the while insisting he is not mad. The visitor then goes on to relate

his own first-hand experience of a Marian expedition to Earth. We read,

“I perceived, directly above me, very close, a luminous transparent

glove, surrounded by immense beating wings – at least I thought I

saw wings in the semi-darkness of the night.” Hardly an isolated

sighting, fiction or real-life, in the 19th century’s explosion of

imagination.

|