from Saturday Evening Post

Eliph' Hewlitt, Book Agent

by Ellis Parker Butler

Eliph' Hewlitt, book agent, seated in his weather-beaten top buggy, drove his horse, Irontail, carefully along the rough Pennsylvania hill road. The horse, a rusty gray, tottered in a loose-jointed manner from side to side of the road, half-asleep in the sun. He was indolence in every muscle except his tail, which thrashed violently at the flies. Eliph' Hewlitt drove with his hands held high, almost on a level with his sandy whiskers, for he was acquainted with Irontail.

The road seemed to pass through an uninhabited region, but Eliph' Hewlitt knew there was a small settlement a few miles farther on, and he was carrying enlightenment and culture to the benighted. He glowed with missionary zeal. In his eagerness he thoughtlessly slapped the reins on the back of Irontail.

Instantly the plump, gray tail of the horse flashed over the rein and clamped it fast. Eliph' Hewlitt leaned over the dashboard of his buggy and grasped the hair of the tail firmly. He pulled upward with all his strength, but the tail did not yield. Instead, Irontail kicked viciously. Eliph' Hewlitt, knowing his horse as well as he knew human nature, climbed out of the buggy, and taking the rein close by the bit led Irontail to the side of the road. Then he took from beneath the buggy-seat a bulky, oilcloth-wrapped parcel and seated himself at the horse's head. There was but one way to get a rein from beneath that tail, and that was to ignore it. In an hour or two Irontail would forget, carelessly begin flapping flies again, and release the rein himself.

Eliph' Hewlitt unwrapped the oilcloth covering from the object it infolded. It was a book. It was the "Complete Compendium of Universal Knowledge, Comprising Useful Information on Ten Thousand and One Subjects, including a history of the world, the lives of all famous men, quotations from great authors, and innumerable indispensable recipes. One Vol. Five Dollars, bound in cloth; seven-fifty, full morocco." Eliph' Hewlitt passed his hand over the gilt-stamped cover affectionately, and then opened it at random and read. For years he had been reading it, and among its ten thousand and one subjects he always found something new which he learned by heart, word for word. A man must know his business to succeed, and Eliph' Hewlitt knew his Complete Compendium of Universal Knowledge.

Suddenly he raised his head. On the breeze there was borne to him the sound of voices -- many voices. He closed the book with a bang. His small body became tense, his eyes glittered. He scented his prey. He wrapped the book in its oilcloth, laid it upon the buggy-seat, and taking the horse by the bridle started in the direction of the voices.

Half a mile down the road he came upon a scene of merriment. In a cleared grove men, women and children were gathered. It was a church picnic. Eliph' Hewlitt took his hitching-strap from beneath the buggy-seat and secured Irontail to a tree.

"Church picnic," he said to himself; "one, two, sixteen, twenty-four and the minister. Good for twelve copies of the Complete, or I'm no good myself. I love church picnics. What so lovely as to see the shepherd and the flock gathered together in a bunch, as I may say, like ten-pins, ready to be scooped in, all at one shot?"

He walked up to the rail fence and leaned against it so that he might be seen and invited in. It was better policy than pushing himself forward, and it gave him time to study the faces. He did not find them hopeful subjects. They were not the faces of readers. They were not even the faces of buyers. Even in their holiday finery the women were shabby and the men were toilworn. The minister himself, white-bearded and gray-haired, showed far more of spiritual grace than of intellectual strength.

One woman, fresh and bright as a butterfly, appeared among them. Eliph' Hewlitt knew her at once as a summer boarder, a refugee from city heat, who had somehow got into this dull, benighted community.

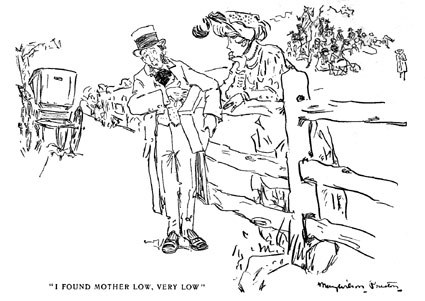

Almost at the same moment she noticed him, and approached him. She smiled kindly and extended her hand.

"Won't you come in?" she asked. "I don't seem to recall your face, but you are welcome to join us."

Eliph' Hewlitt shook his head.

"No'm," he said sadly, "I can't come in. Not that I don't want to, but I wouldn't be welcome. There's nothing I like so much as church picnics. When I was a boy I used to cry for them. But I wouldn't dare join you. I'm a" -- he looked around cautiously, and said in a whisper -- "I'm a book agent."

The lady laughed aloud.

"Of course," she said, "that does make a difference; but you need not be a book agent today. You can forget it for a while, and join us." Eliph' Hewlitt shook his head again.

"That's it," he said; " I can't forget it. I try to, but I can't. Just when I don't want to I break out, and before I know it I've sold everybody a book, and then I feel like I'd imposed on 'em. They take me in as a friend and then I sell 'em a copy of the Complete Compendium of Universal Knowledge, ten thousand and one subjects, from A to Z, including recipes for every known use, quotations from famous authors, lives of famous men; and, in one word, everything worth knowing, condensed into one volume, five dollars, neatly bound in cloth, one dollar down and one dollar a month until paid."

He paused, and the lady looked at him curiously.

"Seven-fifty handsomely bound in morocco," he added. "So you see I don't feel as if I ought to impose. I know how I am. You take my mother now. Hadn't seen me for eight years. I'd been traveling all over these Yewnited States, carrying knowledge and culture into the homes of the people at five dollars, easy payments, per home, and I got a telegram saying, 'Come home. Mother very ill.'" He nodded his head slowly. "Wonderful invention, the telegraph," he said. "Tells all about it on page 562 of the Complete Compendium of Universal Knowledge -- who invented; when first used; name of every town, village and hamlet in U. S. that has a telegraph office; complete explanation of telegraph system, et cetery, et cetery. This and ten thousand other useful facts in one volume, only five dollars, bound in cloth. So when I got that telegram I took the train for home. Look in the index under T. Train, Railway. See Railway. Railway -- when first operated; railway accidents from 1892 to 1904, et cetery, et cetery. Every subject known to man fully and interestingly treated, with illustrations."

"I don't believe I care for a copy today," said the lady.

"No," said Eliph' Hewlitt. "I know it. Nor I don't want to sell you one. I just mentioned it to show you that when you own a copy of the Complete Compendium of Universal Knowledge you have an entire library in one book, arranged and indexed by the greatest minds of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. One dollar down and -- But when I got home I found mother low, very low. When I went in she looks up and whispers: 'Eliph'!' 'Yes, mother,' I says. Is it really you at last?' she says. 'Yes,'I says.' It's me at last, mother, and I couldn't get here sooner. I was out in Ohio carrying joy to countless homes and introducing to them the Complete Compendium of Universal Knowledge. It is a book,' I says, 'suited for old and young, rich or poor. No family is complete without it. Ten thousand and one subjects, all indexed from A to Z, with an appendix of the Spanish War brought down to the last moment, and maps of Europe, Asia, Africa, North and South America and Australia. This book,' I says, 'is a gold mine of information for the young and a solace for the old. Pages 201 to 347 filled with quotations from the world's great poets, making select and helpful reading for the fireside lamp. Pages 463 to 468, dying sayings of famous men and women. A book,' I says, 'that teaches us how to live and how to die. All the wisdom of the world in one volume, five dollars, neatly bound in cloth, one dollar down and one dollar a month until paid.' Mother looked up at me and says: 'Eliph', put me down for one copy.' So I did. I hope I may do the same for you."

The lady was about to speak, but Eliph' Hewlitt held up his hand.

"No!" he said, "I beg your pardon. I didn't mean to say that. I couldn't think of taking your order. I didn't mean to ask it, any more than I meant to ask mother. It's habit, and that's what I'm afraid of. I'd better not intrude."

The lady thought otherwise. She saw in him a pleasant variation from the dull minds she had been in contact with all summer, and she urged him. She said he could try not to talk books, and no one could do more than try; so he climbed the fence with a reluctance that was more noticeable because his climbing was retarded by the oilcloth-covered volume he held beneath his arm.

Mrs. Tarbro-Smith had arranged this picnic herself, hoping; to bring a little pleasure into the dull lives of the natives, and she had succeeded in this as in everything else she had undertaken during the summer. As the leader of her own little circle of bright wits in New York, she was accustomed to do things successfully, and perhaps she was just a little too sure of always having things her own way. As the sister of the world-famous author, Marriott Nolan Tarbro, she was always received with consideration, but for once in her life she wanted to receive consideration on her own account. For that reason she had come to spend a summer in Darkest Pennsylvania, and she had assumed as an impenetrable incognito one-half her name. No rays of reflected fame glitter on plain Mrs. Smith.

The literary side of her nature found enjoyment in the odd types she had fallen among, and her kindness of heart was able to exert itself bountifully. She won the hearts of her hostess and of the dozen or so children of the house with small gifts, and, overjoyed with this, she set about making the whole community happier. Little presents, smiles and kind words meant so much to the overworked, hopeless women that before the summer was half over every man, woman and child was ready to be her dog. They worshiped her, clumsily and mutely, but whole-heartedly. She was a fairy lady from New York.

Her best loved and best loving admirer was Susan, daughter of her hostess, and, to Mrs. Tarbro-Smith, Susan was the long-sought and impossible -- a good maid. From the first Susan had attached herself to Mrs. Tarbro-Smith, and, for love and two dollars a week, she learned all that a lady's maid should know. When Mrs. Tarbro-Smith asked her if she would like to go to New York Susan jumped up and down and clapped her hands. Susan was as sweet and lovable as she was useful.

When Mrs. Tarbro-Smith broached the matter to Mr. and Mrs. Cleghorn she received a shock. She had not for a moment doubted that they would be delighted that Susan could have a good home, fair wages, and a city life, instead of the deadening backwoods existence.

"Well, now," Mr. Cleghorn said, "we gotter sort o' talk it over, me and ma, 'fore we decide that. Susan, she's a'most our baby, she is. T'hain't but four of 'em younger than what she is in our fambly. We'll let you know, hey?"

Ma and Pa Cleghorn talked it over carefully and came to a decision. The decision was that they had better talk it over with some of the neighbors. The neighbors met at Cleghorns' and considered the question openly in the presence of Mrs. Tarbro-Smith.

They agreed that it would be a great chance for Susan, and they said no one could want a nicer, kinder lady for boss than what Mrs. Tarbro-Smith was -- "but 'tain't noways right to take no resks."

"You see, ma'm," said Ma Cleghorn, "we don't know who you are no more than nothin', do we? An' we do know how as them big towns is ungodly to beat the band, don't we? I remember my grandmother tellin' me when I was a leetle gal about the sin and shame she heard of down Harrisburg way, an' I reckon New York is twicet the size o' Harrisburg, so it must be twicet as wicked. So we put it to you plain, without meanin' no harm, that we don't know who you are or what you'd do with Susan once you got her to New York."

"Oh, I know what you want," said Mrs. Tarbro-Smith. "You want references."

"Them's it," replied Mrs. Cleghorn with great relief.

"Well," said Mrs. Tarbro-Smith, "that is easy. I know everybody in New York."

She thought a moment.

"There's Mr. Murray, of Murray's Magazine," she suggested, mentioning one of the great monthly magazines.

"Guess we never heard o' that," said Mrs. Cleghorn.

"Then do you know the AEon? I know the editor."

The neighbors and Mrs. Cleghorn looked at each other blankly and shook their heads.

Mrs. Tarbro-Smith named all the magazines. She had contributed to most of them. Not one was known, even by name, to her inquisitors. One shy old lady asked faintly if she had ever heard of Mister Tweed. She thought she had heard of a Mister Tweed, of New York, once.

Then, quite suddenly, Mrs. Tarbro-Smith remembered her own brother, the great Marriott Nolan Tarbro, whose romances sold in editions of hundreds of thousands, and who was beyond all doubt the greatest living novelist. Kings had been glad to meet him, and newsboys and gamins ran shouting at his heels in the streets.

"How silly of me," she said. "You must have heard of my brother, Marriott Nolan Tarbro, you know, who wrote The Marquis of Glenmore and The Train-Wreckers?"

Mrs. Cleghorn coughed apologetically behind her hand.

"I'm not very littery, Mrs. Smith," she said kindly, "but mebby Mrs. Stein knows of him. Mrs. Stein she reads a lot."

Mrs. Stein, whose sole reading was the Bible and a greasy copy of Pilgrim's Progress, moved uneasily.

"What's his name?" she asked.

"Tarbro," said Mrs. Tarbro-Smith. "Marriott Nolan Tarbro."

"No," said Mrs. Stein, "I don't quite call him to mind. Mighty near, though; I mind a feller once peddled notions through here by name of Tarbox. Might you know him?"

"No," said Mrs. Tarbro-Smith. "I haven't the honor."

"I thought mebby you might," said Mrs. Stein. "His business took him round considerabul, and I thought mebby you might of met him in New York."

Mrs. Cleghorn sighed audibly.

"It's goin' to be an awful trial to Susan if she can't go," she said; " but I dunno what to say. Seems like I oughtn't to say 'go,' an' yet I can't beat to say 'stay.'"

"I must have Susan," Mrs. Tarbro-Smith said positively. "I know you can trust her with me."

"Clementina," said Mr. Cleghorn, "why don't you leave it to the minister? He'd settle it for the best. Why don't you leave it to him? Hey?"

"I'd ought to of thought of that long ago," his wife replied with relief. "He would know what was for the best. We'll ask him tomorrow."

Tomorrow was the picnic day. As Mrs. Tarbro-Smith led the way for Eliph' Hewlitt, the minister left a group of women who had clustered about him and walked toward her.

"Sister Smith," he said in his grave, kind way, "Sister Cleghorn has been telling me you want to carry off our little Susan. You know that we must be wise and sure in deciding the question, and" -- he laid his hand on her arm -- "though I doubt not all will be well, I must think over the matter a while. Welcome, brother," he added, offering his hand to Eliph' Hewlitt.

The book agent shook it warmly.

"'I was a stranger and ye took me in,'" he said glibly. "Fine weather for a picnic."

His eyes glowed. To meet the minister first of all! This was good, indeed. Years of experience had taught him to seek the minister first. To start the round of a small community with the prestige of having sold the minister a copy of the Complete Compendium made success a certainty.

He took the oilcloth parcel from beneath his arm and handed it to the minister, gently, lovingly.

"Keep it until the picnic is over," he said. "I'm a book agent. I sell books: this particular book. Take it away and hide it so I can forget it and be happy. Don't let me have it until the picnic's over."

He stretched his arms in freedom. The minister smiled and led the way toward the place where a buggy-cushion had been laid on the grass as his seat of honor.

"Although," said the minister with a smile, "I don't think you can sell a book here. My brethren are not readers. I read little myself. We are poor; we have no time to read. Except the Bible. I know of but one book in this entire community. Sister Stein has Bunyan's sublime work, Pilgrim's Progress. It was an heirloom.

"Be seated," he said, and Eliph' Hewlitt seated himself, Turk fashion, on the sod. The minister held the book carefully across his knees. Even to feel a new book was a pleasure. His fingers tickled to open it.

In three minutes Hewlitt knew the entire story of Mrs. Tarbro-Smith and Susan. He leaned over and tapped with his forefinger the book on the minister's knees.

"Open it," he said.

The minister removed the wrapper.

"Page 6, index," said Eliph' Hewlitt, turning the pages. He ran his finger down the page and up and down page 7, stopped at a line on page 8, and hastily ran through the pages. At page 947 he laid the book open. The minister adjusted his spectacles and read. Then he pushed the spectacles up on his forehead and looked carefully at the picnickers. He singled out Mrs. Tarbro-Smith and waved her toward him with his hand. She came and stood before him.

The minister wiped his spectacles on his handkerchief, readjusted them on his nose, and bent over the book.

"What is your brother's name?" he asked with deep solemnity.

"Marriott Nolan Tarbro," she answered.

He traced the lines carefully with his finger.

"Born?" he asked.

"June 4, 1864, at Tarrytown-on-the-Hudson."

"And is he married? " he inquired.

"Married Amanda Rogers Long, at Newport, Rhode Island, June 14, 1895."

"Where is he living now? " he asked.

"Year before last he was living with me in New York, but last fall he went to Algiers."

"The book says Algiers. What -- er -- clubs is he a member of?"

"Oh, yes,"she said: "The Authors and The Century."

"It is all right, Mrs. Smith. Susan may go with you."

"One," said Eliph' Hewlitt quickly. "That's just one question that came up flaring and was smashed flat by the Complete Compendium of Universal Knowledge. In that book are ten thousand and one subjects, fully treated by the best minds of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. One subject for every day in the year for twenty-seven years, and some left over. Religion, politics, literature, every topic under the sun, gathered in one grand, colossal encyclopaedia with an index so simple that a child can understand it. See page 768: 'Texts, Biblical; Hints for Sermons, The Art of Pulpit Eloquence.' No minister should be without it. See page 1046: 'Pulpit Orators -- Golden Words of the Greatest, comprising selections from Spurgeon, Robertson, Talmage, Beecher, Parkhurst, et cetery.' A book that should be in every home. Look at P: Poets, Great. Poison, Antidotes for. Poker, Rules of. Poland, History and Geography of. Pomeroy, Brick. Pomatum, How to Make. Ponce de Leon, Voyages and Life of. Pop, Ginger, et cetery, et cetery. The whole for the small sum of five dollars, bound in cloth, one dollar down and one dollar a month until paid."

The minister was slowly turning the pages.

"It seems a worthy book," he said hesitatingly.

Eliph' Hewlitt looked at Mrs. Tarbro-Smith questioningly.

"Yes," she murmured.

"Ah!" said Eliph' Hewlitt, " Mrs. --"

"Tarbro-Smith," she said.

"Mrs. Tarbro-Smith," continued Eliph' Hewlitt, "takes two copies of the Complete Compendium of Universal Knowledge, bound in full morocco, one of which she begs to present to the worthy pastor of this happy flock, with her compliments and good wishes."

"I can't thank you," said the minister; "it is so kind. I have so few books."

Eliph' Hewlitt held out his hand for the sample volume.

"When you have this book," he declared, "you need no others. It makes a Carnegie library of the humblest home."

The entire picnic had gradually gathered around him.

"Ladies and gents," he said, "I come to bring knowledge and power where ignorance and darkness have lurked. I bring you fresh hope --"

When the picnic ended, Irontail had released the rein, and Hewlitt drove off, followed by the grateful looks of the entire community. He had left with them sixteen volumes of fresh hopes at five dollars a volume, bound in cloth.