from Saturday Evening Post

Montana Golf

by Ellis Parker Butler

This man Morley came to the Pokatuk Country Club with old man Burch, and it was with a sort of desperation that Mindaton and I asked the two of them to make up a foursome and play a round. The day was Friday, which is an outlandish day for golf at our club, almost nobody but flappers and half-baked kids showing up on Friday, and Mindaton and I had really gone to the club because we were on the half-sick list and had nowhere else to go. I had a cold and he had a cold and we had meant to loaf in the lounge.

The day was purely punk, if I may be excused for using one of Alaska Vane's most frequent expressions. There was a miserably chilly wind blowing, with dull-gray clouds hanging low, and every quarter hour or so there was a cold drizzle of rain. It was a good day to stay by the fire and that was what we meant to do -- Mindaton and I -- but Dot Carter simply drove us from the club and out upon the course.

We had to get out or die of broken hearts.

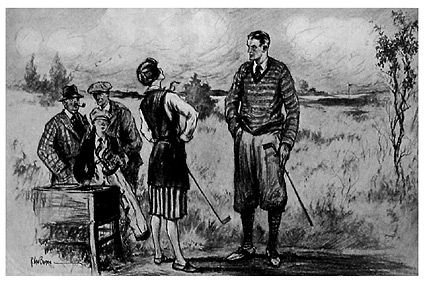

This man Morley -- his name was Jim, or so Burch told us when he introduced him -- was an utter stranger to us, and he was undoubtedly what Burch said he was -- a man from Montana. He looked like a man from Montana. He was all but a full seven feet tall, bony structured and intelligent in an open Western way, and he had a pleasant smile.

He wore his clothes loose and his hat was a near sombrero that was extremely becoming to him. Burch brought him to the table where Mindaton and I were sitting and told us he was a Western customer and a fine fellow, and Morley took a chair and grinned and put one foot on another chair and the other foot on the floor and said we sure had a mighty swell club. Burch then said that Morley was going to be his guest in Westcote for a week or so and that he was giving him a card because Morley was a golfer and played a lot out in Montana.

Morley admitted that he played quite a little and that he had brought his clubs along, hoping to be able to try one or two of the Eastern courses before he went back to Montana. As the talk went on it developed that he played left-handed and had to have his clubs made to order because he was so extra tall, but that he didn't call himself good. About ninety was his gait, he said.

While we were talking there Burch said it was a shame the day was so miserable outside because he had hoped to show Morley over the course.

"Now let me tell you about miserable days," Morley began, and I looked at Mindaton, expecting the Montana man was going to begin one of those tiresome golf stories that strangers are only too apt to tell, but Burch interrupted him.

"What's that?" he asked, cocking his head and listening.

We all listened. It sounded to me like a sob -- like a series of sobs -- and I got up and walked softly to where I could look into the ladies' room, and sobs they were! I tiptoed back to the table.

"It's Dot Carter," I said in a whisper. "She's in there crying."

"It's a damn shame," Mindaton said, and Mindaton seldom swore, even in the rough.

"It's a cursed disgrace!" old Burch said.

"I'd like to kick the young pup until I kicked some sense into him," I said. "What a fellow can see in a painted and powdered war whoop like that Alaska Vane is more than I can see."

"And you can't do anything -- that's the curse of it," said old Burch.

We couldn't, either. From where I sat I could see Bob Roach and Alaska Vane on the veranda, and they were all but what the younger set calls necking. Their backs were to the clubhouse and they were seated so close together at their small table that they might as well have been sitting on one chair, and they were certainly behaving in a mushy manner and as if they did not care who saw them. The miserableness of it was that Dot Carter could do just that thing -- see them. From the ladies' room, they were in plain sight, and they were breaking her heart.

Old Burch grumbled something I could not make out, but I agreed with the sentiment, whatever it was, because I felt quite the same about it; but this Montana man Morley did not know what was what. He asked in a polite enough way what was what. We told him.

From a time long before we built the new clubhouse Dot Carter and Bob Roach had played our course together, and that means from the time when they had to use child-size clubs. They had always been like two clasped hands, and when they became old enough to know love from sour apples they had been in love with each other. Prettiest little mates you ever saw, and, so we all thought, sure to marry some day and be another couple that would be a credit to Westcote. And then this Norbertus Vane moved to Westcote and brought his wife and this daughter Alaska with him, and Alaska hadn't been near Bob Roach three minutes until she made a dead set for him -- eyes, ankles, paint, powder and all -- and had him coming running whenever she lifted an eyebrow. It was a terrible case of infatuation; one of the worst on record.

We hated it, because we did not care for the vamp style in girls and we did like Bob Roach. No finer lad anywhere. Upstanding, clean and as handsome as any male ought to be. And we all knew it was a hard blow to Dot to lose him.

Dot was a nice girl. I don't know any nicer girl than Dot Carter anywhere, but you may know how it is when a girl ties up to one young man for a long while and is looked upon as his. She gets rather out of things as far as other young men are concerned, and if she loses that one young man of hers she is apt to be sidetracked forever. And there was an extra danger of that in Dot's case, because her father was having a rather hard pull with his business. We knew he had trouble keeping up his dues in the club, and rather imagined that he made the effort because of Dot, golf being Dot's meeting point with Bob to a considerable extent.

So pretty much the whole male membership of Pokatuk disliked the way things were working out between Dot and Alaska and Bob. We had a pretty general -- and I think well grounded -- dislike of the Alaska girl. She was loud and noisy and did not belong, but she had Bob eating out of her hand.

Anyway, we sat at our table and tried to talk normally; but those sobs of Dot's kept coming to our ears, and by the time we had told Montana Jim how the land lay and why the sobs, the others of us were jumpy.

"I can't stand this!" Burch exclaimed at last. "Let's -- let's go down in the grill, or -- or go home, or something."

"Why don't we go out and bat around a few holes?" drawled Montana Jim. "I don't know but what I'd sort of like to."

"In this weather?" I asked.

"Well, you fellows know how you feel," Morley said. "Almost any kind of weather suits me to play golf in. If I knew the way around the course I'd give it a try anyway."

Just then Dot sobbed again and Burch jumped up.

"Oh, come on!" he exclaimed in a hoarse whisper. "I can't stand this. I've got to get out of here. Come on, Morley, we'll play a couple of holes. Come on, you two."

I looked at Mindaton and Mindaton looked at me, and we decided that our colds could stand a little fresh air. I went down for my clubs and Mindaton got his from the grillroom where he had left them.

The minute I stepped outside the wind whipped my caddie bag against my shins and Mindaton grabbed for his cap. It was blowing strong and the wind had a businesslike vim that was rather unusual for that time of year. Old Burch and Montana Jim were waiting at the first tee and they had four caddies for us, so we went down to the tee. Burch is one of those men who use a half pinch of sand in making a tee and then push that half pinch into the ground when they put the ball on it, but this time he was using a good wad of wet sand, sinking his ball in it firmly.

"Lot of wind," he shouted as we came near him, and then dodged down to grab his ball, because the wind had blown it out of the hole in his tee and was rolling it away.

"Yes, quite a breeze," Morley laughed as he drew his driver from his extra long bag.

Burch teed his ball again and put his foot in front of it to keep the wind from rolling it, and he held his foot there while we paired off.

Mindaton and I were to play Burch and Morley, we decided, because Morley was Burch's guest, and we insisted that Burch and Morley have the honor, but we couldn't make Morley see it that way. He said we would toss for it, and we did, and Mindaton and I won.

I drove and then Mindaton drove, and then Morley asked Burch to show him the way, and Burch drove. With the wind helping him, old Burch got the prettiest drive I ever saw him get, and when Morley had watched it until it came to rest he opened the pocket on the side of his caddie bag and felt for a ball.

"Pshaw, now!" he exclaimed. "Left all my balls back in Montana!"

"I'll lend you one," Burch volunteered.

"No; that's all right," said Morley carelessly. "I can get along all right without one; better maybe."

"But you've got to have a ball," Burch said.

"No, I don't," Morley said. "Lots of times I play without a ball; mostly, to tell the truth."

"What's that?" I asked, sure I had not heard him correctly.

"I say I don't need any ball," said Morley. "We don't hardly ever use balls out where I play golf. Mostly not."

"Why don't you?" Mindaton asked.

"If you played my course you wouldn't ask," said Morley, smiling. "We've got a wind out there that is a wind. Our course lies along just under the rim rock and the wind blows pretty much all the time, and when she blows she blows. If you knock a ball up in the air that's the last you ever see of that ball. We had to stop using balls on windy days."

"Lost them all?" I suggested.

"Well, not so much that," Morley said, "as on account of the kicks from the ranchers around about. Cattle was all the time getting killed a mile or two mile on beyond. When a man drove a real good drive and the wind got behind it, one of these golf balls would go right through a steer like a bullet through an apple. We've got some wind out there. Yes, sir! I've put a ball down on a tee out there and seen it start right off faster than any man could run, and maybe hit a rock and jump five hundred yards, and that was the last I ever see of it. We mostly play golf without balls out there."

"But how in the world --" Mindaton shouted.

We all had to shout, the wind was so strong.

"Well," drawled Morley, "when a man has been playing golf some while he sort of gets to know how his shot is going to be by the time he ends his stroke. He knows about how far his ball would have gone if he had had a ball. He knows where it would have landed, in the rough or where. A man knows about how many strokes he has to take when he's in a sand pit; he can tell by the way the ball would be lying if he had a ball."

"But I should think," said Mindaton, "that --"

Morley seemed to know what Mindaton was going to say.

"Well, you see," he said carelessly, "we're mostly all gentlemen out where I play. Like you are here, of course," he added. "Gentlemen all, as the saying is. Yes, yes! I lost the club championship just that way last year; took three putts on the seventeenth and Joe Hurley took only two."

"Without a ball?" asked Burch.

"Sure! Without a ball," said Morley. "I knew as soon as I swung my putter for a three-foot putt that I'd missed the hole. I could feel it. 'Missed it by half an inch,' I said to Joe. He shook his head. 'Too bad, Jim, he said. 'Where do you lie?' 'Well,' I says, 'I went a little to the left of the hole and the wind caught me and slung me into that depression beyond the hole, and I lie two feet off to the left there.' 'All right,' he says; 'watch me sink this one.' And sink it he did, just as pretty! 'Your match, Joe,' I says to him, and I went over and sunk my putt. We always play out our shots out there."

Mindaton looked at Morley.

"Fellows," he said suddenly, "let's play this eighteen holes as Montana golf. I like the idea. Let's try it."

"Fine!" I said. "Montana golf it is." And Burch agreed. Morley teed up an imaginary ball and took his left-hand stance.

"I ought to tell you fellows," he said, looking up when he had heeled his club, "that I'm a whale of a driver, mostly, in a wind. It's only fair I should tell you that; I've practiced it a lot out in Montana."

With that he pressed down with the head of his club in the way some golfers do, drew back his club and swung with more power than I have often seen used in a drive. He immediately frowned, handed his driver to his caddie and began hunting through his clubs.

He took out a mashie niblick, walked down from the tee and about twenty feet into the rough just in front of the tee and took a stance there.

"That's just the trouble when a fellow tries to show off before folks," he drawled in his half-humorous way. "I went and pressed that one and topped it good."

"I thought you swung too hard," I said. "You flattened your swing. But why do you have to lie behind that thistle?"

"Well, that's where it went, wasn't it?" Morley asked, and he swung his mashie niblick prettily, taking just a suspicion of turf, clipping the thistle stalk and bringing his club up nicely. .

"That was well done," said Mindaton.

"Yes, I got out on the fairway pretty good that time," said Morley, streaking away with his long legs. He kept his eye on a spot on the fairway, and when he came up to it he asked the caddie for his brassie.

"How do you know your ball lies just there?" I asked him again.

"Well, it's where it went, didn't it?" Morley asked. "It couldn't be anywhere else, could it?"

I am fully justified in saying that I never enjoyed a game more than I enjoyed that game of Montana golf played by the four of us without a golf ball in sight. We are all four, I believe, gentlemen, and there was only one single time in the entire eighteen holes when there was anything like a dispute, and that was when Burch got in the sand pit at the ninth -- a mean place to be. He had taken eight whacks at his ball in his usual vicious choppy style, getting madder and madder each time, and then he suddenly calmed down and got hold of himself and became a rational human being again and made what seemed to me a perfect niblick shot.

"Good!" I exclaimed. "That did it! You're out of the pit!"

"No such thing!" old Burch exclaimed testily. "What have you got to butt in for? You can't see what I did from where you are."

"I know a perfect shot when I see one, I guess," I said.

"You don't know anything," snapped Burch. "I know what I did. Can't you see that overhang of turf up there? My ball hit it and rolled back. Now shut up and let me play this. Ah!"

"You got out?" I asked.

"Yes, I got out," said Burch, and he climbed out of the pit. "You bet I got out that time." But when he was out of the pit and looked at the green he frowned again. "My luck!" he said with disgust.

"What's wrong now?" I asked him.

"Plenty," old Burch said; "I overran the green and went into that edge of rough yonder."

The whole thing was a revelation to me. I had always had a vague sort of idea that the average man if given a chance would be fairly decent, but I had had no idea that honor was so near the surface in all of us. I had had no idea that the average man, if playing on honor, would be not only so fair to the others but so fair to himself. I tried, in that game, to be extra scrupulously fair. I had a feeling that I was being that, but when I came to foot up my score I had a ninety-two, and ninety-two is just about my average game.

In the next week or so Montana golf took a tremendous hold on our club. We men who had played the first game talked about it, and the others took it up and tried it and were enthusiastic about it. Our pro was not so enthusiastic, but that was because he had balls for sale.

Our Montana friend was in big demand during that week or so, showing how Montana golf was played in Montana; but he had time to study the Dot-Alaska-Bob situation too. He made a point of getting Dot off alone and talking with her, and of getting Bob and Alaska to talk, and he talked with Bob alone and with Alaska alone.

One morning I happened to go into the grill and found Montana Jim there having a light breakfast, a mere snack of melon, wheat cakes, syrup, four fried eggs and two slices of ham, and he looked up when I entered. He motioned me to a chair at the table.

I'm wronging Jim; he had sausage too.

"This is great sausage," he said as I seated myself. "I sort of hate to leave this club."

"Going away?" I asked.

"Got to get back to the rim rock and the breezes," he grinned; and then he added more seriously, "You fellows still feel the same about the raw deal that Dot girl is getting?"

"We certainly do," I assured him.

"Well, brother, I heard her sobbing again yesterday," Jim Morley said. "I feel mighty sorry for that girl myself. I've been talking to that Alaska girl some too. She's no mate for that Bob boy. I can get him to quit her, if you say so."

"I wish you could," I said. "We'd all bless you."

"Well, it's your club," he said, wiping his lips and pushing back his chair. "I don't want to butt in if you don't say so."

"If you can make Bob Roach give up Alaska Vane, we are all with you," I told him. "Do you mean to say you can do that?"

"Oh, sure!" he said carelessly. "That's easy."

"If you can, Jim," I said, "we will all remember you forever with gratitude. Do it!"

"If you want I should, all right," he said. "You got to help me some. You and Mindaton, say. I guess maybe I can fix it."

Our Montana friend strolled out onto the veranda, where Alaska Vane was leaning against one of the pillars in her usual nonchalant way, waiting for Bob to come up from the locker room with his clubs. She was dressed in the sportiest of sport clothes and was rouged and lip-stuck to the nines. Jim strolled up to her, giving her a wave of his hand as he neared her, and seated himself on the veranda railing. I could see her begin her usual tricks -- eye work and twisting, as Mindaton called it -- and Jim grinned and talked. Bob came up with his clubs and presently the three of them were talking, and Jim called me over to them.

"Say, George," he drawled, "I been talking to Bob and the lady about that Montana golf we been playing, and they'd like to try it. Wonder if you could find that man Mindaton and make up a foursome and sort of play around. I'd love to, only I got another game on, George."

"I'll get old Mindy," I said, because Jim had given me a wink that meant something, "and I'll be right with you."

"I'm wild to try the game," Alaska said as we walked to the first tee. "Don't they think of the most amusing things out West?"

We paired off with Alaska and Bob playing against Mindaton and me, and because we knew Alaska's game, we played a best-ball game, Bob's or Alaska's best to beat Mindaton's or my best on each of the eighteen holes. We gave Alaska and Bob the honor, and Bob told Alaska to drive.

You probably know women who play the game as Alaska Vane played it. She was breaking all records when she did one hundred and twenty-five for the eighteen holes. She was what might be called a trouble hound. Her game, if charted, would have looked like the chart of a hard-fought football game -- not much progress, but a lot of across and back. Her straightest traveled down the course at an angle of forty-five degrees, like the minute hand of a watch at seven minutes after twelve. She was good at getting into traps, rough and bunkers, but bad at getting out of them, and she putted like a blind woman. She usually played our water hole, which is a pond, by playing around it in the rough. I never saw her drive a full hundred yards.

She began this Montana no-ball game by teeing her imaginary ball until it would have been as high as her ankle, and then she took a stance that was showy but suicidal, swung gaily, lowered one shoulder, stepped back as she swung, raised her head and whanged the head of her club into the turf a good three inches back of the ball -- if there had been a ball.

"Oh, fine!" she exclaimed, looking far down the fairway.

Bob looked at her once, but he said nothing and stepped up to tee his imaginary ball. He swung clean and sweet, handed his driver to the caddie and stood aside for Mindaton and me. We drove.

"All right, let's go!" said Bob cheerily, and he gave Alaska a hand to help her down from the tee mound. She walked through the rough in front of the tee -- sixty yards of it -- and started down the fairway. Mindaton veered off to the left, having gone into the rough, as he knew, and presently I came to where I knew my ball would have been if I had had one, and I used a brassie. Mindaton drove out of the rough with a heavy iron. And still Alaska walked on at Bob's side. Now and then he made as if he was going to speak, but he kept silence. He came to the spot where he felt his ball would have been and he used a brassie. A sweet poke it was too.

"Aren't you somewhere about here?" he asked Alaska as Mindaton and I came up with them.

"Oh, no!" said Alaska. "I'm away up there."

Bob said nothing, but I saw his mouth draw in a little. He cleared his throat nervously. And he cleared it again, meaningly, as Alaska continued to walk up the fairway. She was beyond the spot where the longest ball had been driven by our best professional visitor, and she was still walking.

"Here I am!" she said at last, a good brassie-and-mashie distance from the green. "Give me a mashie, boy."

"I think you ought to use a brassie," Bob said softly.

"Oh, no!" said Alaska. "Not from here, Bob."

She lifted the club and swung gracefully.

"On the green!" she announced.

Now no man living in the present miserable world could have made that green with a mashie. One out of a thousand might have made it with an iron if the iron was exactly balanced and the shot a perfect one. But Alaska Vane made it with a trifling little whiff with a mashie -- and in Montana golf a claimed shot cannot be questioned. Bob Roach reddened and kept his eyes from my face and Mindaton's.

It would be nonsense to detail all the plays of those eighteen holes. This first hole of ours is a par five that I am usually glad to do in a six; but Alaska, being on the green in two, putted out her hole in three. I took seven, Mindaton took six and Bob did a five.

"I would have had it anyway with my five," he said as Alaska teed her imaginary ball for the second.

"That's all right," I said, but he looked nonetheless uncomfortable. He looked even less comfortable when Alaska had driven.

"Where did that one go?" he asked her.

"Straight as a string, Bob," she said. "About three hundred yards."

"I thought you stood a little sideways," he said. "It looked to me as if you had your hands a little too far around on the club. I thought you hit the ball a little high. You didn't top it into that piece of rough over there, did you?"

"Of course not! What nonsense!" she declared.

Bob teed his Montana ball and swung viciously. When Mindaton and I had driven he walked down off the tee mound, letting Alaska do her own getting down, and took a niblick from his bag. He took a stance three feet in front of the tee mound.

"What are you doing that for?" Alaska asked him.

"This is where my ball is," said Bob sullenly. "I topped it."

"You never top them," said Alaska.

"I topped this one."

He chopped at the ball.

"In the sand pit," he said, and Alaska looked at him and her eyes glittered dangerously.

"I see I shall have to win this hole," she said, and she did. It is a par-three hole and she won it in three. One putt was all she took -- on that hole or any other -- during that game. She was playing miraculous golf. She could have used a toothpick or a hairpin and done any hole in par or less. But Bob grew more and more sullen. It hurt him to have Alaska show herself up in that way. We reached the twelfth hole.

Now our twelfth hole is a par three. It is a silly little hole, only one hundred and twenty-eight yards, but we call it the ladies' despair because that is what it is for all but our championship-class ladies. The tee is raised about three feet, but for one hundred yards in front of it is a good stiff weedy rough. Then comes ten yards of fair, ending at a five-foot bunker trapped with sand on either side. If you stand in the sand trap you can't see over the bunker. The green is marked by a bamboo with a red flag, because from the tee the green cannot be seen. It is the most mentally hazardous hole on our course for mediocre players. Most of our ladies play into the rough; the better ones thump into the bunker and roll back into the sand pit. Our best male players use a mashie, throwing the ball high and giving it a backspin, and thus get over the bunker and on the green in one, taking one or two putts for a two or a three. Three is good. Two is extraordinary. Once every two or three years some lucky fellow happens to do the hole in one. Alaska teed her imaginary ball, took a mashie from her caddie and took her stance.

"She will do this one in two," I whispered to Mindaton.

"Yes," Mindaton said, and I saw Bob grow red behind the ears. Alaska drove. She must have missed her imaginary ball by a good six inches one way -- swinging far above it -- and by an inch the other way. It was one of those fluke shots all poor golfers make now and then, missing the ball entirely. Alaska stood immobile, her club gracefully frozen as it was at the end of her swing. She reminded me somewhat of the Winged Victory as she stood there. It was a pose of triumph.

"Bob!" she exclaimed. "I did it in one!"

"I beg your pardon?" Bob said stiffly.

"I say I did it in one!" she declared gaily.

"One what?" Bob asked.

"Why, one stroke -- one shot, you silly!" she laughed.

"Oh! All right!" he said brusquely, and he stepped onto the tee and took a pinch of sand from the box. He bent down and his face was so red it was like an autumn maple leaf. He patted the sand in that way he has and placed the imaginary ball on it -- and straightened up suddenly. "How do you know you did it in one?" he asked in a hard harsh voice he had never used, to my knowledge, in speaking to man, woman or dog.

Alaska looked at him and her face reddened under its rouge.

"I said I did it in one," she said crisply.

"I heard you say it," Bob said, glaring at her. "I want to know how you know it. Can you see through that bunker? You know mighty well you can't -- nobody can. If you want me to tell you something, Miss Alaska Vane, you didn't hit that ball at all. Or, if you hit it, it's in the rough there. You never drove over that bunker in your life, and you never will. If you did drive over it you couldn't know where your ball was until you climbed over the bunker and looked. Nobody could. George Washington couldn't. Abraham Lincoln couldn't. I couldn't. You made this hole in one! You make it in about forty-seven -- that's what you make it in!"

Of course, no woman could stand that. It was insufferably rude and we blamed Bob, but we understood just how he felt. Alaska Vane did her feeling without stopping to think about it. She handed her mashie to the caddie and lifted her head high in the air.

"Thank you!" she said sarcastically. "I understand!"

She turned and started for the clubhouse. Bob did not so much as look after her. He bent down and teed his imaginary ball, looked toward the flag that showed above the bunker. "Fore!" he called, and swung his club. An unfortunate thing happened. In going across our course from the twelfth to the clubhouse one crosses the fourteenth fairway at about half a fair driver shot from the fourteenth tee, and a foursome ahead of us happened to be driving. Blaylock was driving, to be exact, and he drove just as Bob yelled "Fore!" and his ball, traveling low and fast, hit Alaska in the rear, to one side and below the waist. We heard the smack of the ball and saw Alaska jump. To this day, I imagine, she believes Bob Roach intentionally drove that ball at her. And it was no mere Montana ball that hit her!

We played out the eighteen holes and on the way back to the clubhouse Mindaton tried to say something to Bob, but he silenced him.

"Cut it!" he said. "I've had my lesson. I'm through with her. I'm a golfer and I've always been a golfer, and I'll always be a golfer, and I can't stand a person who doesn't play fair. I never suspected this, but I know it now, and I'm glad I learned the truth in time. Men, there was not one shot she made today that she counted fairly -- not one!"

"We couldn't say anything, of course," I said.

"You were fine," Bob said. "Not one shot she counted fairly!"

Half an hour after we reached the clubhouse we saw Bob and Dot together and I never hope to see a happier face than Dot's was.

Montana Jim Morley came to where we were seated and slumped into a chair. He grinned at us.

"Worked?" he asked.

"It certainly did work," I told him. "He's off Alaska for life, or I'm a poor guesser. All we need do now is clinch it."

"Clinch it?" asked Montana Morley, pausing in his job of rolling a cigarette with one hand.

"Show old Bob the difference between the two women," I said. "Have him play a round of Montana golf with Dot."

"Hey! Off it, you!" cried Montana Jim with excitement. "Don't you go and do that. Great cats, no! Say, you're a governor of this club, ain't you? Well, you call a meeting and pass a rule against Montana golf, and pass it quick! Don't you let that Bob boy play any game of Montana golf with that Dot girl. You'll spoil it all; you'll spill the beans."

"And why shouldn't Bob play Dot a game of your Montana golf?" Mindaton asked.

"Why, thunder and blazes!" cried Montana Jim. "You ought to know that; this Dot girl is a woman too."

Well, maybe so. I don't know. Somebody else will have to fight that out. But there's one thing we do know over here at Pokatuk and you can take it for what it is worth --

Mindaton dropped into the club yesterday and accosted me.

"George," he said, "you remember that Montana man old Burch brought to the club?"

"Old Montana Jim, the man who rolled cigarettes with one hand and taught us Montana golf?" I said. "I certainly do remember him, and a good scout he was too."

"Yes; that's true enough," Mindaton said. "But I met old Burch just now, and what do you think? You remember that Alaska Vane girl? Our Montana Jim Morley married her the week after he left here."

"Yes?" I said, and I could not think of anything much to say. "Well, maybe he liked her," was what I did say. And maybe he did.