from Leslie's Monthly

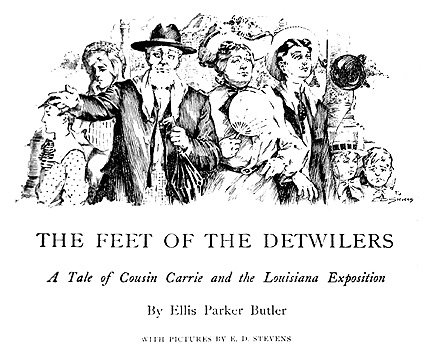

The Feet of the Detwilers

by Ellis Parker Butler

"You just mind what I tell you," said Gramma Detwiler, from her seat of honor in the rickety willow rocking chair, "if you never sensed that you had legs in your life before, you'll sense it before you've been on them show grounds two days."

The Detwilers were going to St. Louis -- "the hull kit and boodle of them," as Gramma said -- Ma and Pa Detwiler, Willyum, who was twenty-two, Mary who was twelve, Jawn, aged ten, and the two babies, who were nine and seven. Only Gramma and Peter were to remain at home; Gramma because of her age and Peter because he reckoned he would go down a little later on.

"I wisht you wouldn't say legs so often, Gramma," Ma Detwiler said. "It ain't proper. It don't sound nice."

Gramma laughed in her peculiar manner, which was much like a chuckle.

"Go 'long with you, Sally," she said, good-naturedly, "when a person gits to my age legs is legs, whatever they was once. And I don't know any better name for 'em."

"If I felt called on to mention them," said Mrs. Detwiler, "I'd say ankles."

"Well, Sally," Gramma said, "when you git to trottin' 'round them show grounds, if so be it's as big as the State Fair, I guess you'll git a notion you've got legs the same as anybody else."

"Above all," said Gramma Detwiler, when the "hull kit and boodle" of Detwilers, little and big, had kissed her goodbye, "keep your eye out for Cousin Carrie from Oklahoma. I can't for the life of me remember who Aleck's second wife's oldest boy married, and it bothers me terrible not to remember, and Carrie would know, bein' as she lives in the same town. If you see her you ask her. She's most sure to go to St. Louis, she's teachin' school now, an' earnin' good wages. You'll know Cousin Carrie if you see her. She's just a year an' three months below Willyum."

"Now, above all," said Pa Detwiler, when they were safely landed in the Union Depot at St. Louis, "I want you all to look out sharp for Cousin Carrie. Gramma's so set on us meeting her."

It was noon by the time they reached their hotel and washed up a little, and when the family had eaten a dinner made uncomfortable by the knowledge that a colored waiter was hovering over them, the men folks went out to have a look at the street, and Ma and the children found a quiet corner by the hotel parlor window.

On their return the men folks found Ma bursting with eagerness.

"Pa!" she exclaimed, "I'm just sure I saw Cousin Carrie! I was sittin' right here at the window lookin' out an' she passed right by carryin' a grip valise. I made a motion at her with my head. She didn't seem to notice, but I'm most sure it was her."

"What's she look like?" Pa asked, for none of the Detwilers had ever seen their Cousin Carrie.

"Well," said Ma, "she was sort of youngish lookin' an' neat."

"Shouldn't wonder if it was her," Pa said.

"Oh! I guess if it was her, we'll likely run across her out on the grounds," said Ma hopefully. "Will we go out today?"

"I reckon not," said Pa, "Me an' Willyum will take the two boys down to have a look at the river, an' you an' Mary might go an' look at the big stores."

"Well, I'm tired!" said Ma Detwiler, when the family met in the evening. "I'd ought to have broke in these new shoes before I left home. The stores are wonderful crowded."

"Didn't happen to see Cousin Carrie, did you?" asked Willyum.

"We saw one girl we was sure was her," Ma replied. "She was pricing hats. Mary was so sure it was Cousin Carrie that she asked her, but it turned out it wasn't. Seems she was from Kentucky."

The first glimpse of the fair was a surprise to the Detwilers. Their American habit of unmoved acceptance of whatever it might be their lot to see was shaken. The greatness of the buildings, the greenness of the lawns, the cumulative beauty of the whole, surprised them. As they stood before the Central cascade, Pa Detwiler even forgot how hot his new coat was.

"Sally," he said, "so long as I've lived on God's green earth I never looked to see nothin' like this! It's fine!"

Ma Detwiler, a baby on either side, was still a woman, and divided her attention between the scene and the other women. When the family moved on, she held her skirt in a manner quite unknown in Kilo. Such environments sanctioned style.

"All I wish," she said, "is that Gramma Detwiler could be here! She'd get the real good of it. I'm sort of afraid of it."

They spent their first day on the grounds wandering about in a rather aimless manner, viewing the exteriors of the buildings, and keeping an eye apiece for Cousin Carrie. Occasionally, Willyum would spread out a large folding map of the grounds and figure out where they were at the moment, and trace the way to the entrance. It gave them a sense of not being lost, although they were utterly lost most of the time, and as often as not Willyum was wrong in his idea of where they were.

Willyum and Mary were eager to see the Iowa building, and the family walked several miles as directed by Willyum from his map, but finally gave up the search, after having all but stumbled over it. They also sought the Oklahoma building, where they felt pretty sure they would find Cousin Carrie, but were unable to locate it.

"There!" exclaimed Ma Detwiler as they were making their way toward the exit, "Mary, see that girl just ahead? Don't that look like what you'd take your Cousin Carrie to resemble? Just run on and look back in her face. Maybe it's her."

"Ma, I've run after so many girls already, my feet are just dead," complained Mary. "I just won't run after this one."

"Willyum, you go," said Ma Detwiler, "you'll do that much for your Gramma."

Willyum overtook the girl, who was alone, and as he raised his hat, she stepped back, a little frightened, and Willyum blushed.

"Excuse me," he said, "are you my Cousin Carrie from Oklahoma?"

The girl shook her head and moved on hastily. Willyum perspired freely and felt miserable. He stood awkwardly while the girl walked away.

"'Twasn't her," he said shortly, when the family came up.

The next day Mrs. Detwiler's feet were so sore she could not go to the grounds. Mary had made friends with two young girls at the supper table, and as she had freely anointed her feet with witch hazel, she was able to go with them. Pa Detwiler took the two babies, and Willyum went alone. Willyum went to the Pike. He began with the first show, visiting one after another and it was noon before he was aware of it, and his feet were so weary that he started for home. He wandered about until he reached the Art Palace, and to escape the heat and perhaps find a seat, he entered.

To Willyum, art was new. In the presence of these paintings he felt abashed and clumsy. As he passed from one picture to another, he knew he was enjoying himself, but he felt vaguely out of place. He edged up to the groups of sightseers and tried to catch what they said about the pictures. He was intensely lonely.

Once he paused before a picture of a rock-bound coast, on which waves were dashing, and the desire to speak overpowered him. Two kind looking ladies stopped beside him and eyed the painting critically, and Willyum said, "Great, ain't it?"

The ladies looked at him with surprise, and moved hastily away.

He was dying to have someone to talk to, and his legs were aching. He dropped into a seat before a huge historical scene, and eyed it languidly. Then a smaller canvas caught his eye -- a group of peaches -- and tired as he was he saw that they were real. He arose and walked over to have a close view. On one of the peaches a dew drop clung -- you could see it sparkle. On another a bee lazily rested. Willyum was astounded. Never had he believed that art could so wonderfully mimic nature. He glanced around and, seeing he was unobserved by the guard, he touched the bee lightly with his finger. It was indeed painted. He went back to his seat, and found a young woman occupying part of it. She was the girl he had spoken to the previous afternoon. She made room for him.

"Say," he burst out, "do you mind if I speak to you? I've been trottin' 'round this place all afternoon and seems like I'd bust for some one to talk to."

"Yes," she replied, "I felt the same way. I was so glad to see somebody I'd seen before that I could have shouted. It tickled me to see you touchin' that bee with your finger. I done the same thing. Awful natural, ain't it?"

"Beats anything I ever saw," Willyum said. "I'm kind of stuck on this part of the show, I guess. First I ever saw of this sort of thing."

"Me too. I teach school out West, and I said the first thing I'd see would be the Palace of Education, but I haven't seen it yet, but somehow I always get in here every day."

"I've got to see most everything yet," said Willyum, "but I'd set my mind most on the Agriculture show. I'd like to come here often, but I guess I'll have to take in a different building every day."

"I set out that way, too," said the girl, "but my ankles get so tired I can't keep up to my programme, and when I get so's I can't walk, I just come in here and pick out a nice picture and sit and rest and look at it. I guess everybody's got tired feet here."

"Ma's ankles give out yesterday," said Willyum briefly. "She's at the hotel soakin' in witch hazel."

"I know," the girl said, "I feel every morning that I'd rather stay in bed than see anything on the grounds, no matter what, but I didn't save up my money all winter to pay for a nap, so I just pull myself out of bed and start out. Does your Ma's feet bother her bad?"

Willyum smiled.

"There ain't a foot in our whole family that ain't ready to be put out to soft pasture, I guess," he said. "Mine feel like they'd been stepped on by an elephant."

The girl glanced at him, half shyly and half archly.

"I came to St. Louis alone," she said, "but I have a brother-in-law out home who's a druggist, and before I left he gave me four boxes of salve for the feet. You don't know how it takes out the soreness. I'd like your mother to have a box of it."

"She'd be mighty pleased," Willyum said eagerly.

"I don't just know how to get it to her," the girl remarked carelessly, "unless I send it by mail."

Willyum pondered the matter.

"Well, say," he said, "why can't you bring it along tomorrow and then I could get it? Say I meet you here at eleven o'clock. I guess Ma will be able to be out tomorrow. I'd like to have you meet Ma, anyway."

"I'd like to meet her," said the girl, and the conversation lagged.

"Goin' to look at any more pictures today?" asked Willyum presently.

"I'd like to, now I've got somebody to talk about them to," said the girl, "but I guess my ankles are too tired.

The next day Ma Detwiler was very stiff, and the whole family was footsore. They took a certain pride in their tiredness.

"I only wish your Gramma could be here," said Ma Detwiler. "We musn't let another day pass without finding Cousin Carrie. I thought of nothin' else all day yesterday."

The day was insufferably hot. Pa and Willyum stewed in their heavy black coats, and the white handkerchiefs tucked in their collars only partially preserved the starchiness. They wore their vests unbuttoned.

"Today," said Pa Detwiler, "we'll all go down the Pike. I guess Cousin Carrie will likely take in some of the shows there."

Willyum had not mentioned the girl at the Art Palace. He said he had seen the Pike, and he wandered away from the others. He found the girl before the bee picture, but neither of them mentioned the magic salve. They spent the forenoon strolling through the Art Palace. Willyum did not think of Cousin Carrie once.

After lunch -- of which the girl insisted on paying her share -- they took a trip in a sun-baked gondola at a price that Willyum considered outrageous.

The Detwiler family, returning from the Pike, were lamely dragging the babies around the Grand Basin, which glared in the sunlight, when Mary stopped suddenly: --

"Ma!" she exclaimed with great excitement. "Look there! Willyum's found Cousin Carrie! They're ridin' in that boat."

"I declare if he ain't!" said Ma. "And to think of us speakin' to dozens we thought was her today, an' him with her all the time! Well, Willyum usually beats out this family. He takes more after Gramma than any of us does."

"She's good-lookin', ain't she?" said Mary, "but both of them looks as if they was scairt of bein' drowned. Let's hurry around to the next landin' an' meet them."

"It ain't no use doin' that Mary," Pa said, "we can't catch up with that skiff, an' I guess Willyum will bring her to our hotel this evenin'."

Willyum was rather late getting back to the hotel, and he went at once to the dining room. He did not burst out with the news that he had found Cousin Carrie, although the family kindly waited that he might have that pleasure, reserving their knowledge as a further surprise.

"Well, Willyum," said Ma Detwiler, at length, "anything new today?"

William balanced a piece of potato on his knife blade while he shook his head.

"No, Ma," he said.

"Didn't you see Cousin Carrie?" his mother asked.

"I saw plenty that might have been her," he said carelessly.

One of the babies, finding it impossible to remain silent longer, interrupted.

"Willyum," he said, "how does it feel to ride in a gondoleer?"

Willyum's face turned crimson.

"That was one of the girls you thought was Cousin Carrie," he said. "I run across her yesterday, and she said she had some salve that would help Ma's feet. So I made out to meet her today and git it. I guess that's all right, ain't it?"

"If her salve will help my feet any," said Ma Detwiler, "I'm right glad you met her."

Willyum blushed again.

"I guess I forgot to git it," he said weakly.

"Willyum," said his mother sternly, "you want to be careful how you take up with strange women in a place like this."

"Now, Ma," said Willyum, "I don't call her strange. You took her for Cousin Carrie, yourself. An' she wants to meet you tomorrow. She's a nice girl."

"If she meets me tomorrow," Ma announced, positively, "she's got to come here. I don't stir out of this hotel. My legs have plumb give out."

"Ma," Pa Detwiler teased, "ain't it a little improper to say 'legs' in public?"

"No, it ain't," she replied, "ankles is ankles, and mine is sore; and feet is feet, and mine is frazzled; but them two things don't begin to give no idea how bruised and achy and worn out my legs is."

"Shaw, now! Sally!" said Pa, soothingly, "I'm as bad off as you are; my legs is sore clean up to my shoulder blades!"

The next day Willyum asked for the salve as soon as he met the girl.

"I guess we'll all be glad to use this," he said. "There ain't one good foot left in our family. This fair is the widest spread out and the hardest underfoot of anything I ever saw."

They wandered rather aimlessly, content to be together.

"Is it called polite where you came from," said the girl, "for a man to look after all the girls he passes when he's walkin' with another lady?"

"Don't mind me," Willyum pleaded, "it's a habit I've got into. I reckon I'll never git over lookin' at girls. I've got a third cousin, and she's likely to be here and the whole family's lookin' for her.

"I guess most everybody's sort of expectin' to meet folks they know," she replied, "everybody expects everybody else to be here. I kept lookin' for some of my folks the first week, but I'm over that now."

Willyum pointed to where a man was dragging two small boys along a walk.

"That's Pa," he said, "he's tryin' to ketch up with that girl ahead, who looks like she might be our cousin. He won't get her. He's too dead tired to walk fast enough."

"He's real handsome," the girl said. "Are them your brothers?"

Willyum started forward quickly.

"Wait!" he said.

He saw a girl ahead who might be Cousin Carrie, and he pushed his way after her. Once he smiled back to where his companion stood, and then he went on. The girl he was following must have been a new arrival for she walked briskly, and Willyum could just keep her hat in sight. The more he studied her hat, the more sure he was that she was Cousin Carrie. When, at length she stopped, she was not Cousin Carrie. When he reached the statue by which he had left his companion, she was gone.

He waited half an hour, and then wearily trudged to the Art Palace, where he took his seat before the peach picture and waited. When he went to the hotel that night, he realized how tired he was. He was cross and the whole family was cross.

"I don't believe we've got a Cousin Carrie," he said, "like as not she died and is buried out there in Oklahoma."

"Maybe she lost her position and couldn't save enough to come," said Mary.

"Might be she's come and gone again," Ma suggested. She did not like to think of unpleasant things.

"Well," said Willyum, "I say don't let's look for her any more. If she's here she's likely lookin' for us, an' she's got six chances to our one, bein' there's six of us an' only one of her."

The family heaved a great sigh of relief.

"It'll be like a different thing if we don't have to look for Cousin Carrie," said Ma. "That's what wore me out. I had to keep movin' for fear I'd miss her. If I can just go somewhere an' set down, I'll enjoy this fair myself. I won't say but it's been a task so far."

"I guess we've done our duty by Gramma," Pa said.

For several days thereafter Willyum went somewhere and sat down. He looked at the peach picture so long that he might have been taken for its partner, but the lost girl did not come. She had gone home.

The things the Detwilers did not see were more numerous than those they did. Every great exposition is like a three-ring circus -- you can't see all of it -- but they stored up a great deal to tell Gramma, and took back to her a trunk full of catalogues and free souvenirs.

At every meal Gramma said, "I'm so sorry you didn't see Cousin Carrie," and to every tale of the fair she said, "And you do tell me it is bigger than the State Fair! Well, land's sakes, I'm glad I staid home."

Willyum, on Sunday, put on his best coat, and putting one hand in a pocket felt a hard, round package. It was the box of salve.

"Ma," he said, "here's that salve that girl gave me. I plum forgot it."

"Why, Willyum!" his mother exclaimed. "And my feet so bad all that time!"

She looked at the label.

"I declare!" she said. "Why, maybe that girl knew Cousin Carrie. This come from Farway, Oklahoma, and that's where Cousin Carrie's at. Who was that Cousin Carrie's sister Jo married, Gramma? Wasn't he a 'pothecary?"

"His name was Wilbur, Cornelius Wilbur. He kep' a drug store."

"Gosh!" Willyum cried, "I was with Cousin Carrie nearly a week and I didn't know it!"

"And to think," said Gramma sadly, "that you was right with her an' you didn't ask her who Aleck's second wife's oldest boy married. I dassay I'll go to my grave not knowin'."

Willyum's eyes gleamed.

"If you feel so eager about it, Gramma," he said with poorly feigned indifference, "I guess mebby I can scare up time to write to Cousin Carrie and ask her."

And then he blushed.