from Rotarian

Collar-Button Casey

by Ellis Parker Butler

I'll bet you never heard of Joe Casey's celebrated Pony Express that made just one trip and something like a million dollars. Joe Casey is the same Casey that had his picture -- full page -- in the magazine last month, with "Collar-Button Casey, the man who made a million dollars in collar-buttons" under it, and an article five pages long telling all about him. But the man who wrote the article missed a lot by not digging up the original facts.

Back in the days when Casey had his original idea nobody had heard the word "service" as meaning what it means now, although even then not a few men were getting an extra dividend of happiness and satisfaction out of business by handing out "what you pay for -- plus something." There have always been a few such men; there are more of them now; there can't be too many. They are the salt of the business earth.

When I looked at the picture of Casey in the magazine the other day I hardly knew him for the youngish fellow I got acquainted with a good many years ago. He is plump now. Back in the old days he was a skinny six-footer with a thin Irish face, red hair that was a regular mop, an Adam's apple that stuck out like a closed fist, and blue eyes that were always laughing at you.

Casey had a wife and three kids -- as he called them -- and the oldest was a boy. This boy, Jamie, was eight years old and he had a pony -- an over-size, half-breed Shetland that was as fat as a barrel of army pork and as sleepy as a full-fed cat. Casey's wife was a Hetterbury, and her father -- the boy's grandfather -- had sent the pony in from the farm. He thought it would be a nice present for the boy and it is quite likely that he had an idea that he would just as lief let Casey pay for the pony's board and lodging anyway, a pony of that sort being just about as much use on a farm as a pair of white spats would be.

Anyway, the boy got the pony, and Casey bought hay and oats and straw for it, and the boy and the pony were great friends. Once in awhile, just to amuse the boy, Casey got astride the pony and rode around the yard, and he was a sight! When he let his legs hang his feet dragged in the grass, and when he put his toes in the short stirrups his knees came up to his chin. Casey used to say that he could not ride the pony with his toes in the stirrups because, when the pony walked, Casey's knees hit his Adams apple and choked him. He little thought, when he told me that with an Irish grin, that he would some time make a dash on that pony that would be more important -- for Casey -- than Paul Revere's famous ride.

At that time Casey ran a small haberdashery shop on Main Street in our village of Westcote, New Jersey, and he lived away out on Twenty-eighth Street -- a long walk from his shop; but he was long legged and did not mind the walk. He had no telephone in his shop, because he did not see how he could afford one, but he had one in his house because the neighborhood was so far from the butcher and grocer. Telephones were new then and most of the store-keepers considered them an infernal nuisance, but the men who had the germ of the service idea put them in. In those days no man looked upon the telephone as an aid to business, they were put in as a convenience for the customers who happened to have them.

Casey's haberdashery came close to being the least common divisor in the business line in Westcote. It was what we call a "half store" -- about ten feet wide, one half of a twenty-foot store that had been cut in two by a lengthwise partition -- with one narrow window squeezed in alongside of the door. Casey could not make much of a display in the window and he could not carry much of a stock in the store, which was rather lucky for he did not have much capital to carry stock with and his bank credit was just about enough to get him a loan of one hundred dollars for thirty days if two reputable millionaires would indorse the note. The truth was that Casey had been a rather gay young lad and he had not quite lived it down.

In his telescope-shaped shop Casey carried a fair to middling stock of shirts and collars and such things. They were mostly cheap and flashy because his trade was mainly among the young fellows who had been his gay-day associates, or others of the same sort, who liked to drop in and chin with Casey and swap stories with him. There were three other haberdashers in Westcote and one was an old concern that had the reputation that years of business brings, and a stock that filled a big room forty feet wide and a hundred feet long. It happened one afternoon that Casey sat on the shelf back of his counter rubbing a wart that was on the back of his neck and thinking it was about time he did something to make his business jump up on its hind feet and make a sound like a real concern. The reason he had gotten onto that train of thought was that the annual Westcote Assembly Dance was being held that night and Casey's wife had said something about rather wishing she could go to the Assembly dances. They could not go, of course. Casey had no evening clothes and could not afford any, and his wife had no swell evening gown and could not afford any, but -- just the same -- Casey's two younger kids were girls and he would have been a poor guesser if he could not have guessed that his wife had a hope that, if she could never expect to attend the swell Assembly dances and mingle with all the upper tendom of Westcote, her daughters might when they were old enough -- which would be in a mere ten or twelve years.

"Th' divil!" Casey said.

There did not seem to be any way to make his little rabbit of a business leap up suddenly and roar like a lion. He was still toying with that wart on the back of his neck when Carter Miller opened the door a foot and a half and stuck his head in.

"Say," he said. "I don't suppose you've got a size 16, white madras dress shirt, have you?"

"Come in!" said Casey.

Miller entered the store reluctantly. He was in a hurry, just as he always was.

"Well, have you?" asked Miller.

"You want it for the doings tonight" said Casey. "I have not it, but I'll have it for you. You'll not be wanting to rig up till after dinner, I'm thinking. Lave it to Casey, and a shirt that will fit ye like the paper on the wall will be handed in at your door before ye cool yer coffee."

"Now, look here!" said Miller. "I don't want to be disappointed --"

"Not a chance!" said Casey. The wife will be in here before ten minutes passes to touch Casey for twelve dollars and eighty cents, which is the price of an elegant chapeau she saw the advertisement of in the New Work paper this morning, and she's got to be back to cook the potaties for the kids for dinner. Lave it to Casey!"

"Well," said Miller doubtfully. "I'll have to, I guess. I've been all over town. A man can't expect you fellows to carry all sorts and sizes of dress shirts in a village like this, I suppose. All right; I'll trust it to you! Before seven, now! I'll depend on you."

"Anything else, sir?" asked Casey.

"No. Yes!" said Miller. "Have you any white ties? No? Well, get me two. Not the kind that are already tied. That's all."

Mrs. Casey came in just as Casey had said she would, and she carried the specifications to New York and brought back the Number 16 white madras shirt and the two ties. Casey walked a mile and a half out of his way to deliver the shirt and the ties and walked home again; that was all part of the day's business. He ate his dinner and rocked little Mary to sleep and then peeled off his shoes and put on his knit slippers and settled down for a quiet evening.

"There was a felly in the store today that told me a joke," he said to his wife.

"What was it? Tell me; I love jokes," said his wife.

"He says to me, 'Casey, do you know who the meanest man in the world was?" Mr. Casey began, but his wife howled and threw a ball of yarn at him, for this was the thousandth time Casey had heard that joke and the thousandth time he had told it to his wife. The only joke in that old joke was in telling it to his wife again, making her think she was going to hear a new one.

You know what the joke is -- the meanest man in the world was the man who was so mean he used the wart on the back of his neck for a collar-button. It can't be done -- not comfortably, anyway -- for Casey had tried it when he heard the joke for the first time, but that did not stop people from telling him the joke. The collar buttons in his showcase reminded them of the joke and they told it to him.

Casey was giggling at his wife and unhooking the yarn that had looped over his ear when the telephone jingled. He sat up straight and so did his wife, for not once a week did their telephone bell ring.

"It's the telephone!" Mrs. Casey exclaimed, much as she might have exclaimed "It's the ghost of your grandmother!"

"It's the telephone!" exclaimed Casey. "Now, who the divil would be --"

"Maybe it's Mrs. Gandy got hers in already," said Mrs. Casey. "She was saying on the train this afternoon she thought she would have to have one. But would she get it in so soon?"

"No," said Mr. Casey. "It takes time."

"Then who do you suppose it is?" asked Mrs. Casey anxiously.

"I could not guess in a million years," said Casey. "I'll go and find out."

Casey went into the back room, where the telephone was, and took down the queer, old-fashioned receiver.

"Hello!" he shouted at the top of his voice, for that was necessary in those days, or so people thought.

"Winchy winchy winchy winchy winch!" came back a thin little trickle of sound that sounded like nothing at all.

"Hey! Hello! Hello!" shouted Casey. "This is Casey's house! Casey! This is Casey's house! Cay-see! Cay -- see! On Twenty-eighth Street! I can't hear ye!"

"Winchy winchy winchy winchy winchy!" squeaked the telephone in Casey's ear.

"Here; wait a minute!" shouted Casey. "I'll get the wife. I can't hear a dang thing ye say. Ellen! ELLEN! Come here and see if you can hear what the dang thing is tryin' to say!"

A mile and a half away Mr. Carter Miller was standing in his lower hall, barefooted and clad only in a bathrobe and a suit of neat underclothes, and behind him his wife was standing in almost equal negligee, wringing her hands. From moment to moment Mr. Miller turned the handle of the telephone angrily; then he spoke into the telephone.

"Is that Mr. Casey? I want to talk to Mr. Casey?" he shouted, and a mile and a half away the sound was reproduced as something like "Winchy winchy winchy winchy winch!"

"This is Casey's house!" Mr. Casey was shouting. "Cay -- see! CAY -- SEE! On Twenty-eighth Street! I can't hear ye!" And what Mr. Miller heard was "Shreaky shreaky shreaky shreaky shreak!"

"Oh, Carter, do let me try!" cried Mrs. Miller. "Please do not get so violently angry. There is really no need of cursing the telephone so awfully. Let me try; I can nearly always make people understand."

"Come here, Ellen, and talk to the dang contrivance; I never could make head nor tail out of it," Mr. Casey was saying.

"Try it then, if you are so wonderful," said Mr. Miller to his wife, as he handed her the receiver.

"I can nearly always understand what it says," said Mrs. Casey to her husband as she took the receiver from him.

"Hello!" screamed Mrs. Miller. "Is that Mr. Casey the haberdasher?"

"This is Mr. Casey's wife -- wife -- wife!" shrilled Mrs. Casey.

"Wife?" queried Mrs. Miller.

"That's all right," said Mr. Miller impatiently. "Tell her. She got the shirt for me. Tell her."

"Mrs. Casey!" cried Mrs. Miller into the telephone. "You got a shirt for my husband this afternoon. Yes, shirt. For my husband."

("It about the shirt we got for Mr. Miller," said Mrs. Casey to Mr. Casey.)

("Drat the shirt!" said Mr. Casey. "Whenever a man tries to do a man a favor --")

("Hush! She's talking," said Mrs. Casey.)

"The shirt is all right," screamed Mrs. Miller.

("It's not the shirt," said Mrs. Casey to her husband. "It must be the ties; she says the shirt is all right")

"And the ties are all right," screamed Mrs. Miller.

("She says the ties are all right, too," said Mrs. Casey, aside, to Mr. Casey.)

("Then what's she kicking about?" asked Mr. Casey?)

They would have known well enough if I they could have seen Mr. Miller a few minutes earlier. Mr. Miller, conscious that he had, no doubt, a first-class white madras dress shirt, No. 16, and two new white dress ties that were the kind one ties himself, had eaten his dinner in leisurely fashion. He had bathed in luxurious style and had shaved slowly and carefully. He wished to look his very best for he had been given a great honor -- he had been asked to lead the opening grand march. All his life he had hoped that some day he might be asked to lead the opening grand march of the Assembly ball and now the honor was his. Mr. Miller, returning to his bedroom from the bathroom, had opened the parcel that contained the shirt and the two ties. They met with his full approval. From the shirt he had been wearing he took the two collar buttons, and these he put on his dresser. He then brushed his hair, got his dress suit from its place in the closet of his room, placed his patent leather pumps where he could not possibly forget them, and picked up the shirt again. He took the two collar-buttons from the dresser and, with them in his hand, prepared to insert them in the buttonhole of the shirt-band.

For twelve years or more Mr. Miller had never had collar-button troubles. For twelve years he had had but one pair of collar-buttons. Day after day he had taken them from one shirt and put them in another and he had never lost them. And now, at what seemed to him the most important moment of his life, the two collar-buttons chose to behave as collar-buttons behave in comic pictures and in jokes; they leaped from his hand and disappeared. Instantly Mr. Miller was on his knees, pawing under the dresser. No collar-buttons! He looked under the bed. No collar-buttons! He crawled around the room, feeling behind legs of beds, legs of chairs and along the wall edge. No collar-buttons! He swore and his wife cried out with horror. No collar-buttons! Absolutely no collar-buttons ! It was evident that the two sinfully mischievous collar-buttons had waited for twelve years for this moment and had jumped down the register.

"It is a peculiar thing to ask," shrieked Mrs. Miller into the telephone, which whispered in turn to Mrs. Casey, "but my husband has lost his collar-buttons. Collar-buttons! He lost them! They went down the register!"

("She says her husband lost his collar buttons down the register," said Mrs. Casey to her husband.)

("And what have I got to do with his collar-buttons and his register?" asked Mr. Casey sarcastically.)

"She says she knows it is a queer thing to ask," said Mrs. Casey, "but her husband wants to know if you would be so very, very unusually kind and obliging as to bring him two collar-buttons to his house right away?"

While Mr. and Mrs. Miller stood at the other end of the telephone wire so slightly clad, Mr. Casey felt the wart on the back of his neck and then scratched his mop of red hair.

"Tell him," he said to Mrs. Casey, "tell him the collar-button express starts for his mansion in one-half of a minute."

"But have you any collar-buttons here?" asked Mrs. Casey.

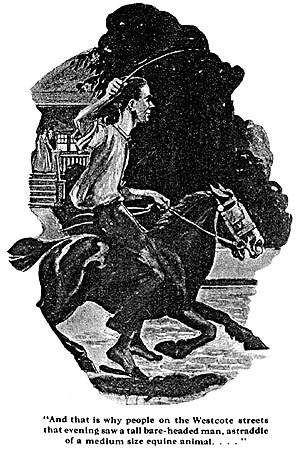

"Two," exclaimed Casey. "One befront and one behind," and he unbuttoned his and cast it aside. From his collar-band he took the two collar-buttons, and wrapped them in a wisp of paper. He did not stop to put on his shoes. He did not stop to get a hat. And that is why people on the Westcote streets that evening saw a tall, bare-headed man, astraddle of a medium-sized equine animal, wearing one red wool slipper and slapping the haunches of the fat beast with a whip, as the animal ambled through the twilight like an extra-fat rocking-horse.

When the pony reached Mr. Miller's house Mr. Casey rode up to the front door. He did not have to ring the bell; Mr. Miller opened the door and grasped the small package that contained the collar-buttons.

"Thanks!" he cried. "See you tomorrow! Thanks!"

When Casey reached his own home and had put the pony in the shed he went into the house.

"Ellen," he said, "I don't know what kind of man that Miller man may be, but if I don't get his trade from now on he's a snake!"

Toward the middle of the evening Casey chuckled. "Did you think of another joke?" his wife asked.

"I did!" he declared, grinning. "Another collar-button joke. And a good one, for there's a business end to it, the same as to a wasp. Listen, Ellen, from now on I maintain and advertise the Pony Express for the delivery of collar-buttons. Casey needs no collar-button; he buttons his collar on the wart of his neck. But Casey knows the collar-button is a child of Satan; it loses itself at the moment you most need it and when there's not another in the mansion. From now on Casey the Haberdasher, Telephone No. 88, will maintain the Pony Express for the sudden delivery of collar-buttons when most needed. 'If you lose your collar-button, telephone Casey.' Would folks talk about an advertisement like that, Ellen? Answer is, 'They would!'"

That was the origin of Casey's celebrated Pony Collar-button Express, famous in Westcote in its day, but it was far from the end of the collar-button episode. But once more, to tell the truth, was Casey called upon to make the hasty ride to supply collar-buttons to an unfortunate that had lost them, but the "Collar-button Casey" name that stuck to him turned his thoughts more than normally toward collar-buttons, I suppose, and that was what made Casey.

Mr. Miller, it turned out, was not a "snake." Now and then you do find a man who does not appreciate service, but not often. Miller dropped into the haberdashery the next day to pay for the shirts and white ties and collar-buttons, and after that he dropped in often, either to make purchases or to smile with Casey over the collar-button express idea. He claimed a part in that, as the reason why it existed. He was almost as proud of having lost his collar-button as of having led the grand march at the Assembly ball.

One evening, just before he closed his store, Casey put his hand into his showcase and into the cardboard box that held a hundred or more cheap collar-buttons, to take out a dozen or so. He meant to take them home in order to have a supply there in case of sudden demand.

The collar-buttons were cheap ones. They were brass and to shield the neck of the wear from the corroding base, which -- when wet -- made a green spot, the maker had devised a thin covering of white celluloid for the base. As Casey held the collar-buttons in his palm he looked at them and his eye rested on the plain white base.

"A sinful waste!" he said to himself. "A man could have his name and business printed on that bit of white. And why not?"

Casey did it. He did more than that. On one thousand of the cheap collar-buttons he had printed "Compliments of Cellar-button Casey," with the number of his shop and "Main Street, Westcote."

Almost before the buttons had arrived he had ordered another lot -- five thousand this time. For Casey had an idea. With every purchase, however large or however small, he wrapped in one collar-button. If anyone asked for a collar-button Casey gave one. But, particularly, he put into the neck-band of every shirt he sold two collar-buttons, one "behint" and one "before," and with every collar he sold he gave a collar-button.

It would be a pleasure to say that, because of his collar-button generosity -- a form of service -- Casey was now the head of a chain of haberdashery shops reaching across the continent. It cannot be said. It would not be true. Casey does not now own even one such shop. The shop he started does not even exist today.

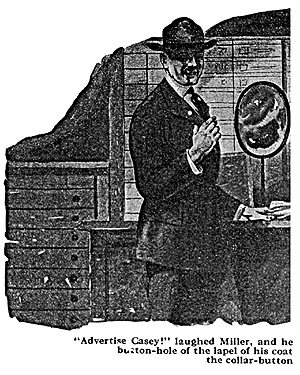

One afternoon Mr. Miller dropped into Casey's shop and Casey, as was his little joke always when Miller dropped in, handed him two of the celluloid backed collar-buttons.

"Advertise Casey!" laughed Miller, and he slipped one of the collar-buttons into the buttonhole of the lapel of his coat with the printed white base of the collar-button outermost.

As Casey's eyes widened and his mouth fell open Mr. Miller imagined the haberdasher was going into a fit.

"Here! What's the matter?" Miller asked. "What ails you?"

Casey drew a deep breath and then grinned naturally.

"I had an idea, or -- leastways -- half of one," he said.

And that is the whole of Casey's story. The craze for buttons was just coming in then -- lodge buttons, political campaign buttons, all kinds of celluloid buttons. Casey's idea was a most simple one. The usual celluloid advertising button, once its day is past, is as useless as a crab's left hind leg after the crab has shed it.

"Instead of a pin on the button," said Casey to himself, "why not have the celluloid be the back of a regular collar-button? When its day is past as a Blaine-Logan signal a man can wear it to keep his collar on. It's an idea, anyway."

The rest, you may have read in that magazine I was telling you about. Casey found that the cost of the collar-button was little more than the button with a pin. The concern known as "Collar-button Casey, Incorporated," has but two real stockholders. One, of course, is Casey; the other is Miller, the man who appreciated, service even before "service" was its name.

The Westcote Assembly ball is, I may mention, now held each year in the handsome new Casey Community Hall, and usually one or another of the young Caseys leads it. And why not when dad is a millionaire?