from American Legion Magazine

The Collecting Mania

by Ellis Parker Butler

Consider this mania folks have for collecting things. Take this hobby for collecting second-hand postage stamps, for instance. I am willing to stand up in church and announce that the most sissified thing a great big able-bodied man can possibly do is to spend hours and hours of precious time gathering together a lot of annulled, defaced and ex-officio postage stamps and pasting them in albums. In the utmost seriousness I declare that I think this thing of collecting discarded postage stamps to be the lowest form of mental exertion of which a man is capable. And that is, I shouldn't wonder, why I have been a tireless postage-stamp collector for fifteen years or more. It does a man a lot of good to know he is doing something absolutely idiotic and non-sensible, and to have a real good time doing it.

The trouble with the world is that it is getting to be so full of intelligence and ethics and sense that it is not worth living in any more. A man can't buy a dog that looks like a dish-mop nowadays without first getting ready to make an affidavit that it is a full-bred Czecho-Slovakian heath-hound, and worth seventy-five dollars, and useful for catching rats. There was a day when a fellow could pick up any old pup in the alley and all the excuse he needed was that he loved it. A man once upon a time could wear whiskers because he liked their looks; now he has to say he wears them because he has throat trouble. Nobody ever gives a boy a dog now because a boy likes a dog; the dog is given because -- so the bluff goes -- taking care of a dog teaches the boy kindness, consideration, politeness, respect for the American flag, how to care for the teeth, gums and tonsils, and arithmetic. I admit here and now that the reason I collect postage stamps is because it gives me a few minutes of completely idiotic inanity of mind now and then. I collect postage stamps because there is no reason in the world, that I can imagine, why I should.

In my opinion that is the finest thing about collecting anything, aside from collecting bills. In a period when you can't sit down with a man to have a dish of vanilla ice cream without having him explain that he eats it because it contains 1256 calories and seven gross of vitamins it is a godsend to have something foolish that can be done. My father for many years was a bookkeeper. When I was a small lad I discovered that I was able, by resting my left heel on the floor and raising the left side of that foot, to bend my big toe downward from the end joint and make it crack with a loud snapping sound. I demonstrated this to my father with no mean pride.

"Yes," he said, "I see! But I don't believe that is an accomplishment that would be of much service to a bookkeeper."

Right there I think he was wrong. I think all serious-minded bookkeepers should learn to crack their toes or wiggle their ears or indulge in some other harmless and useless amusement, such as collecting old furniture or patent medicine bottles of the hoop-skirt era. Indulging in such time-wasting pastimes is folly of the deepest dye, but no man is a wise man until he learns to be considerably numerous sorts of a fool.

Collecting postage stamps, to my notion, ranks near the top of all collecting because there is nothing quite as useless as a cast-off postage stamp, unless it is a worn-out automobile tire, and even they can be sold as junk. The only objection to collecting postage stamps is that the collector can usually sell his collection day after tomorrow for more than he paid for it day before yesterday, and that postage stamps -- being so small and flat -- are just about the most compact and convenient things to store.

These two are serious objections, I admit. They prevent the postage stamp collector from feeling absolutely weak-minded and irresponsible, which is the feeling we need.

This thing of feeling that we must be rational has gone too far. It has gone so far that the man who picks up a pin because it is lucky to pick up a pin feels he has to tell you that he has picked up the pin because it will come in handy. He will try to spoof you with a long explanation regarding how his wife's mother is always asking him for pins, and how his wife is always asking him for pins, and how his daughters are always asking him for pins, and how he tries to keep a few pins under his coat lapel because the house he lives in has such steep stairs and it is hard on an old lady like his grandmother to have to climb the stairs for a pin. And the man who picks up a pin because he thinks it may come in handy sometime does just the other thing -- he tells you that he does not pick up the pin because he is the sort of man who picks up anything that is lying around lost, but that he believes there may be something in this idea of picking up a pin being good luck.

The world is jammed full of men who go fishing for their health and play golf to avoid anemia and hardening of the arteries -- to hear them tell it. We need more men who collect brass jugs and are willing to admit that it is merely and solely because they have a bug in the bean. We need more plain unadulterated foolishness scattered around or one of these days we will all go crazy.

I have been a collector, and always with limited means at my disposal, since I was a child. I had a twenty-five-cent stamp album and was collecting stamps a few days after I climbed out of the cradle and fell on the floor for the last time. I "exchanged" with boys in other towns, for none of the boys I knew were simple enough to waste time with stamps, or if they were they did not tell me. In those days Harpers Young People, of blessed memory, printed free "exchange ads" inside the front and back covers, and one ad would bring letters from dozens of boys. We kept the lists and did a big business trading "three mounted specimens of sea moss from Pacific Ocean" for "ten stamps from Russia, Germany and France." We traded anything that could be tied up in a package and sent by mail. When I saved up a few pennies I sent them to someone who advertised "five large pennies for 10 cts."

No one ever got a "complete" collection of anything. We could collect postage stamps by the hundreds but we never completed the stamps of any one country. We would buy and exchange and get a fine array and then run up against the "rare" varieties that cost real money -- fifty cents or a dollar -- and we would lose hope and start exchanging everything we had for something else. We would begin to collect cent pieces of every year of issue, and run up against the place that could not be filled unless we were millionaires and had $2.50, and we would start exchanging again like mad.

Some of the lads who put "exchange ads" in the columns of Harpers Young People had a well developed business instinct. A favorite "exchange ad" was one that read: "Will exchange twenty varieties European stamps, no two alike, for a silver dime of any issue." That, however, was commercializing the game. Even I guessed that that exchanger was not entirely bent on securing a complete collection of dime coins, and I was as innocent as most, in those days.

Oddly enough, I can't remember what became of my juvenile stamp collection, although I probably exchanged it for something else -- coins, most likely, for I had a good collection of copper coins until I exchanged its constituent parts for coins of the size of silver dollars. I built up quite a collection of those -- five franc pieces of various mintages, Mexican dollars, American trade dollars coined for business with China, Spanish, English and German coins, and so on, all approximately the size of our silver dollar. I got some of these by exchanging, but I got more from the merchants in town and from one of the bankers. The coins were "passed" on the merchants or taken at a discount by them, and they would sell them for a good whole-souled American dollar any time. I got a lot of them, for by that time I was out of high school and working, and had some spending money.

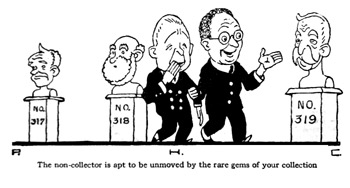

To anyone who has not been collector of one kind or another I can hardly explain the delight of securing an addition to my collection as I felt it in those days. I cannot remember ever feeling the same pleasure upon receiving my wages or even when receiving a present of money. To find a new coin or, earlier, to go to the post office and be handed the letter that I knew contained a wanted stamp, was an exquisite delight. It was a culmination of a wished for happiness. I think that explains why the collecting mania gives so many rational people such disproportionate pleasure. A collection is never complete. And though you think you have a pretty good array, the non-collector is apt to be unmoved by the rare gems of your collection. He will even yawn as you point with pride.

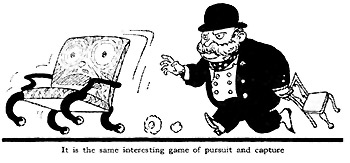

A collector is, let us say, trying to gather together examples of all types of Chippendale chairs in the genuine article. He begins his hunt for a shellback French-type Chippendale chair and while he is hunting it he has all the pleasure of pursuit. He finds the specimen and he has, for a moment, the joy of acquisition. It is a most amazingly satisfying feeling. He has gone a-hunting for one particular thing and he has hunted it down and bagged it. He has it. The next moment has a new and equally insistent desire -- he must get an authentic specimen of the Chinese Chippendale chair. It is the same interesting game of pursuit and capture. And with the bagging of the Chinese Chippendale he begins a new hunt for a Chippendale Gothic chair. It is endless and the appetite increases with each success. Every day the collector learns more of the technic and finely specialized details. What he comes to know about Chippendale furniture is as truly knowledge as anything else. He comes to be a wise man in his chosen field of collecting and he enjoys being wise.

A few years after the Spanish War, when I was in Paris, the antique shops fascinated me, and in the window of one I saw a shell cameo I rather admired and I bought it. I paid less than a dollar for it -- about ninety cents, if I remember rightly -- and I immediately began collecting cameos. It was one grand excitement and the best fun I had in Europe, any time or any place. In those days the cameo had not had its revival, as it has had since then, and they were cheap, and the hunt had the additional zest that I did not know seven words of French.

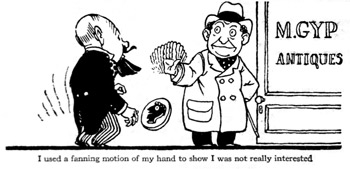

But in spite of this I found buying cameos in Paris great fun, as it is to buy anything in antique shops when you know what you want and really want it. The method, of course, was the old one of entering the shop and asking the price of something I did not want, deciding it was too high priced, and then asking carelessly what that cameo cost. This is the method every collector should use on all occasions.

The dealer expects it. It is supposed to be the ultimate of cleverness and to hoodwink the dealer and catch him off his guard. I used to follow it up by a fanning motion of the hand to indicate that I was not really interested. The only trouble is that the dealer thought of it before I was born. It is such an old trick that once when I went into a shop and asked the price of a cameo the first thing, and then bought it, the dealer dropped dead. If it had not been that his wife was in love with the janitor next door and had intended to poison her husband that evening at dinner I might have been in serious trouble. As it was she made me a present of the cameo and it is one of the most prized in my collection, because it has a history.

In collecting cameos I ranged all over Paris and I did not spend much money because I did not have much. I bought quite a number of shell cameos before, being the rankest kind of amateur, I discovered that the stone cameos were the most desirable. I found one ancient Roman cameo cut in lava, possibly before Pompeii was destroyed. In a box under the stalls of a book-seller on the quais I found the remnants of some cameo-maker's stock -- blanks of oval shape cut from the shell but not yet carved, cameos partly completed, cameos evidently done by apprentice hands. In the studio of a Spanish artist I found some Spanish cameos of great crudity but of considerable charm and unlike the vast mass of cameos, which are Italian. I found one early shell cameo showing the three graces, most exquisitely carved on a brown shell -- not so common -- and I found another with a head of Minerva, as delicately cut as any I have seen. I found three dainty little cameos no bigger than match ends.

I had shifted from shell cameos to stone cameos when I met my Nemesis. Stone cameos, cut in agate of all colors, are irresistible, and I had begun buying them when, in a good shop near the Invalides, I ran across a Napoleonic cameo pin with which the dealer said he could furnish authentic documents proving it was given by Bonaparte to Madame So-and-So. I forget her name. The cameo was dark agate, set in a frame that had a dozen small diamonds and was about as big as the first joint of a man's thumb. The cutting left a profile bust of Napoleon in relief in dull white, and across the brows was a wreath of leaves in gold. When I examined the wreath to see how it was held in place I turned the pin over and found on the back a most delicately carved Napoleonic bee, little larger than the head of a pin. The cameo had been drilled and this bee was the flange or nut or washer on the end of the minute gold bar that connected with the wreath and held it in place.

Well, I felt sick when I heard the price! It was not more than I could pay, but it was a lot more than I ought to spend for any cameo in the world, bar none. I went back to that shop again and again, fretting and whining like a Scotch terrier at the wrong end of a rat hole, feeling that life would not be worth living if I did not own that cameo, but frightened stiff for fear I might have to go hungry and then swim the Atlantic to get back to America. It was the year of the bank panic, when none of the banks in New York had any cash; my money was in a New York bank. When I went to my Paris bank it told me a draft might be honored and it might not, but the papers were full of the Grand Crash Americaine, and the bank did not seem hopeful about it.

There you have one of the real joy of collecting. Pay after day and week after week and year after year we collectors come plump face to face with the most delightful agony. It heats the pleasure of the small boy who lusciously bites down on his sore tooth to see just how much it hurts. Continually we meet temptation in its most thrilling form; we are endlessly finding something we positively must add to our collection and positively cannot afford. If we grab Old Man Temptation by the neck and strangle him and don't buy the cameo we swim for days in sweet agony of regret, and if we let Old Man Temptation whack us on the head and we do buy the cameo we swim for just as many days in an even sweeter agony of remorse and contrition, flavored with the joy of possession. No one can understand this unless he has experienced it. Mighty few people except collectors know how much pleasure can be got out of suffering.

I had a perfectly grand time over that Napoleonic cameo and I might have suffered all that spring and summer if someone had not told me there was a nice little collection of cameos in the Bibliotheque Nationale. That's the National Library, and the last place I would have looked for cameos. I had always thought a library was where books were kept and, being an author, I never go to libraries. But I went to see the cameos in the Bibliotheque Nationale.

One look was enough. It took me about two minutes to decide that with my income and the time at my disposal it would take me about four million years to get together a collection of cameos that I could mention without a blush of shame after seeing one sixty-fourth of the collection in the Bibliotheque Nationale. I saw at once that as a cameo collector I ranked about minus zero. The Bibliotheque Nationale seemed to rank cameos like the Napoleonic one over which I had yearned as also ran and selling plater, and did not bother to show them in less than ten gross lots. My memory is not very good, but there were little trifles like a whole seashell as big as my head carved in the year 43 A. D. with a representation of the conquest of Troy, showing 864 warriors and a job lot of gods and goddesses that would fill a first-class pantheon and spill over.

There were unimportant little items like the cameo Nebuchadnezzar wore in his crown, and the cameo Noah carved on the Ark while waiting for the high water to evaporate. I don't know but that there was a cameo carved by Adam. If they did not have that one then they probably have it by this time. I went back to our pension and began collecting postage stamps. There is one thing about postage stamps that is comforting -- the first stamp was issued in 1840 and there is no danger of strolling into a museum and finding one issued by King Solomon to commemorate the visit of the Queen of Sheba.

The idea of collecting postage stamps seems to have originated with boys -- girls, for some reason, never seemed to take to it, possibly because they find greater pleasure in collecting the boys. There are some women now who have notable collections, but they probably went into it on an equal rights platform, and because they felt they ought to do it if men did it. A list of the men who collect postage stamps would be a surprise to most people. It would include kings, senators, financiers, generals and many notable men in all professions. Army and Navy men are, frequently collectors. Collections worth a million dollars are not talked about much; collections worth thousands of dollars are so common that they excite no comment whatever unless they contain some especial rarities. The Scott postage stamp catalogue lists a 10 cent stamp issued in Baltimore in 1845 at $8,000, one issued the same year in Alexandria, Virginia, at $10,000, and one issued the next year at Boscawen, New Hampshire, at $12,000. There are at least thirty stamps issued in the United States that are quoted at $1,000 or over -- probably more -- and a rapid glance through the latest catalogue shown at least 155 postage listed at over $100 each.

The above do not include stamps printed on envelopes or revenue stamps. The two-cent vermillion stamp, printed on an envelope in 1880-1882, for example, is worth $200. If someone who bought a five-cent box of matches made by the Maryland Match Company back in Civil War days had saved the one-cent revenue stamp that was printed on watermarked paper and pasted on the box, he would have made a good investment, for the stamp is now worth $225. These figures are for United States stamps only, a very small part of the catalogue, and stamps of other countries worth hundreds or thousands of dollars are amazingly numerous you'll find if you investigate.

I doubt, for example, whether many know where. New Britain is -- I don't mean the Connecticut city. Its first issue was as late as 1914-1915, but one stamp is worth $125, one is worth $150, five are worth $200 each, one is worth $600, one $350, two $400 each and two $600 each, and there are a number so rare that no prices are quoted. New Brunswick, the next country in the catalogue, has stamps quoted from $125 to $800. An unused Newfoundland shilling stamp of 1860 is worth $1,000, but you can buy a cancelled one for $500. On the other hand you can't get a 6 1/2 pence stamp of the same year for less than $1,250, and it would probably require quite a hunt to get it at that. You can see that an enthusiastic boy whose father has a mere four or five million dollars could easily bankrupt papa and still not have much of a collection.

On the other hand there are thousands of stamps of almost no value. You can buy 10,000 mixed United States stamps for $2.50, which is almost less than nothing each, and I have a quotation on mixed foreign stamps of $1.95 for 10,000. The small dealers will show you sheets containing hundreds of stamps, no two alike, from which to choose at a cent or a half cent each. On these cheap stamps some dealers will give a discount of 90 percent -- for a stamp listed at one cent you pay only one-tenth of a cent.

The original idea of the boy when he began collecting stamps was to get "every kind of stamp there was". This is the "general collection", and it includes all countries, but to complete such a collection is such a manifest impossibility, both on account of the time required and the money involved, that most of the advanced collectors have become specialists. This means that they collect only the stamps of one country, one group of countries, or of one period. There are even collectors who specialize in one stamp only, as, for example, the United States three cent red stamp of 1851-1856, collecting all the minute variations, different postmarks, etc., of that one stamp. You may not believe it, but such a collection is intensely interesting.

In my own case I began with a general collection, then got rid of all but the stamps of France and the colonies and possessions of France. Thousands of others, about the same time, dropped general collecting and specialized in one continent -- as South America, Europe, or Africa. The stamps of Great Britain and her colonies made a fine field. But even these grand divisions presently became too large for the man of average means to handle. Some began collecting stamps of one or two countries only, or the stamps issued by certain countries in the nineteenth century only or in the twentieth century only. The pleasure was quite as great and the possibility of securing a reasonably complete collection was greater.

There are now thousands of thousands of adult stamp collectors in all parts of the world and there are thousands of dealers, but to secure a stamp needed to fill a spot in an album the collector must often consult dozens of dealers and wait for years until some collection is broken up, and all the while there are more collectors entering the field, stamps are being destroyed by fire or otherwise and prices are mounting. In 1916, when I began collecting the stamps of the little Grand Duchy of Luxemburg, the first four stamps issued (in 1852) were listed at one dollar for the first two and three dollars for the second two, each. They are now worth four dollars for the first two and ten dollars for the other two, each. The highest priced stamp was then listed twenty dollars; it is now forty dollars. But this is not all. Many of the stamps could then be bought at less than list price; now more than list price is gladly offered for many of them.

But the real fascination of stamp collecting I have hardly touched upon, if I have mentioned it at all. It is in the expert knowledge that comes with the specialists' study of their stamps. This is akin to the dog fancier's knowledge of the fine points of the particular breed of dogs he likes best, or like the flower-lover's interest in the delicate variations in tulips or dahlias. I might put it this way -- a raw collector might begin by wanting one stamp from each country of the world, and be interested until he has that collection complete. Any stamp will satisfy him. Presently he will want to have one stamp of each denomination of each country of the world -- one cent, two cent, three cent and so on. Then he may feel that it will be better to try to collect every stamp of one country, and decide on Luxemburg.

He almost immediately discovers that when he has the ten centime lilac stamp of 1865-1872 he has not everything he can have in that stamp. Some of the ten centime stamps printed in those years were lilac in color, but some were rose lilac and some were gray lilac, and he has to have those. Then he discovers that the Luxemburg post office printed over the face of some of these stamps the letters OFFICIEL, meaning they were to be used on public business only, and he has to have that stamp. But he also discovers that, by error, some of these overprints were printed twice on one stamp, or three times on another. He has to have these double surcharges and triple surcharges before he can be truly happy. Or, it may happen, one of the plates from which the stamps were printed was marred and the "s" in "centimes" is missing. This happened on every sheet of stamps, and he has to have one of the stamps with the "s" missing.

This may seem foolish, and it is, but it is part of the game, and so many otherwise responsible men are wanting that stamp that its price goes up. If the ordinary ten centime stamp is worth a dollar in open market and there are one hundred stamps to each printed sheet the one with the "s" missing may be worth a hundred dollars, or it may be worth ten dollars -- it all depends on how many specialists there are wanting that stamp. He tries all the dealers and does not find a copy, so he watches the auction catalogues and when he sees the stamp listed he bids for it. Usually the other fellow gets it, and he begins his hunt again. He writes to dealers in Luxemburg, in London, in Paris. He is a lucky fellow when he finally nails that stamp.

Practically every stamp ever issued can be made a specialty in this way. A man can collect varieties of the Boscawen, New Hampshire, five cent stamp at $12,000 a throw, and when he has one his collection is complete, because only one is known to exist, or he can collect varieties of the ninety cent stamp of 1860 at $800 per stamp and spend enough money to build a court house, or he can specialize in the three cent stamp of 1917, which is worth almost nothing. Probably an earnest collector could gather ten thousand varieties of this last stamp -- or more -- and be able to point out how each stamp differed from every one of its follows. There are innumerable shades of violet in this particular stamp, from a vivid violet that is almost purple to a wishy-washy violet that isn't much of anything. Millions of this stamp were issued by the Government. One variety not perforated on the sides is worth $25 today and will go higher.

The rare stamps are so valuable that they are not handled with the naked fingers, but with tiny tongs made for the purpose. A reason why so many of the older stamps are rare now is that the early collectors pasted them flat to the album page with glue. The stamps had little value. When a new album was needed the owner tried to peel the stamps from the old page and ten out of every hundred were torn and then thrown away. When a modern collector thinks of the stamp treasures that were destroyed in this way his hair stands on end and he has nightmares for a week. Now stamps are affixed to album pages with thin transparent peelable hinges.

The leading association of stamp collectors in America has about 2,700 members, practically all adults, and twenty-two branches, and it holds an annual convention. It was incorporated in 1886. In New York the stamp collectors have a club and maintain rooms where, last season, seventy auction sales were held. The club has a library of between 3,000 and 4,000 bound volumes, and between 40,000 and 50,000 magazines, all devoted to stamp collecting. Twenty-seven of the world's best stamp magazines are received there regularly. I give these figures because they are impressive, but I collect postage stamps because it is fun.