from Popular Magazine

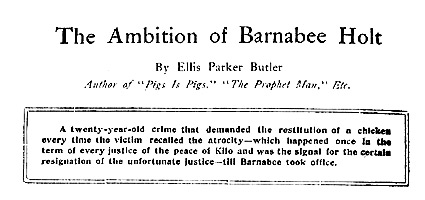

The Ambition of Barnabee Holt

by Ellis Parker Butler

The town of Kilo -- it is all on Main Street, Cross Street, and Higgins Lane, where there are two houses -- is not wildly lawless. It broils in the sun and freezes in the snow of the Iowa prairie, and it has no saloons. Its three hundred inhabitants have enough to do without wasting time breaking the laws, or perhaps it would be better to say that two hundred and ninety-nine of them have. Kilo has, at times, its lawless element, and that lawless element is old Rodge Williams. This is the story of how Barnabee Holt, justice of the peace, tried to suppress the lawless element.

There was a tradition in Kilo that the incumbent of the office of justice of the peace, retiring from office, was in line for the office of State representative. In the early days, when the bare prairie had been settled by the soldiers returning from the Civil War, that had been the rule. One term as justice of the peace, then State representative. It was a good rule, and avoided unpleasant wrangling among less-qualified aspirants, but Rodge Williams come to town over the B., C. R. & N., and spoiled everything. Thereafter, the office of justice of the peace became a nuisance to its holder. It was a potato, cool enough when taken in the hand, but getting hotter and hotter, until it had to be dropped.

The trouble was that old Rodge Williams was everybody's something-or-other. If he wasn't a cousin he was a tent mate, and if he wasn't a tent mate he was an uncle, and if he wasn't an uncle he was a friend of the postmaster. Any one in Kilo could sit down and tell you all the ramifications of old Rodge Williams' family and friendly connections, and when he was through telling there was hardly a voter omitted.

When he was sober, old Rodge was a good, but idle, citizen. He could sit on the shiny side of a pine bench as long and as hard as any other man in Kilo, and his war stories were as interesting as the average. When he began "D'jou remember that day when we was marchin' from --" half the listeners nodded acquiescently, for they had marched with Rodge, and the tale was apt to be one in which they had played a part. The only trouble was that when old Rodge managed to get hold of liquor -- as he did in the mysterious ways known to temperance towns -- he became a man of one idea His idea was that Dave Roscoe owed him a chicken. His whole desire then was to get that chicken.

The origin of the chicken affair was lost in antiquity. It had to do with some "settin's of Plymouth Rock eggs" of a superior quality furnished by old Rodge to Dave Roscoe, and to be repaid in hatched chicks, and a consequent quarrel over the number of chicks Dave had given Rodge. Twenty years had passed since the unfortunate quarrel, which had been amicably settled between the two men at the time and after a few weeks of enmity, and only when he was in liquor did the memory seep up through old Rodge's brain and become an obsession. Then he was able to think of but one thing -- Dave Roscoe owed him a chicken, and would not give it up, and, by Harry! old Rodge was going to have his rights.

The way old Rodge "got his rights" was by going to Dave Roscoe's chicken yard and taking them and a hen at the same time. In the twenty years old Rodge had repaid himself that chicken forty times. Sometimes Dave caught him with the hen in his hand in the chicken coop; sometimes he caught him on the way back to his one-room home; sometimes he caught old Rodge frying the chicken on his stove, and sometimes only the feathers in old Rodge's back yard told that he had stolen a chicken. After about ten years, this began to be annoying to Dave. He swore that if Rodge "bruk into his hencoop oncet more" he would "have the law on him," and he did. At least, he tried to.

He had the marshal arrest old Rodge for chicken stealing, and took him before the justice of the peace of the day. Something less than two hundred of old Rodge's cousins, nephews, brothers-in-law, tent mates, and old comrades in arms immediately spoke to the justice of the peace about the case. It was a difficult position for the justice of the peace. On one hand was the book of the law and the evidence duly presented, or about to be presented, and on the other hand was the clamor of loving friends and relatives pleading that old Rodge be not made the cause of disgrace to one and all of them through a jail sentence. The justice of the peace worried over the matter for two days, and reached a decision worthy of Solomon. He resigned his job. Since that first resignation old Rodge had been the thorn in the flesh of every succeeding justice of the peace. Things would be running in oiled grooves, nothing to worry the justice, and all at once old Rodge would find liquor, and Dave Roscoe would drag him into court, one hand on old Rodge's arm, and the other holding a dead chicken or a handful of speckled feathers. He demanded justice, and the justice promptly resigned. Not one justice ever completed his term.

Barnabee Holt took office with high hopes of reaching the capitol at Des Moines. He was sixty -- a ripe age for a legislator -- and he was a Republican in a county so overwhelmingly Republican that Democratic ballots were printed merely as a matter of form. The holder of the office of justice was in line for the representative's toga. Old Rodge Williams was the only possible pitfall in his path, and Judge Barnabee took precautions. Once, long before, there had been a town night watchman, but he had made his rounds two nights only when he began to get nervous of weird night noises and resigned. Judge Barnabee looked up the town statutes and discovered the office still existed, and induced the mayor to appoint Thad Carter night watchman. He called Thad and the day marshal to his office and gave them their instructions.

"There ain't nothing in the way of lawlessness in this town," he said, "except a tramp now and again, and you fellows ain't going to have much on your hands. Maybe during the day you'll have to look out that the boys don't play ball against the side of the Methodist church and break them colored-glass windows, and once in a while Enderby's pig gets out of that bad corner of his pen and goes for Mrs. Wallis' garden, but except that you ain't going to have hardly enough to keep you amused. There ain't nothing at all for a night watchman to do, Thad. You got a regular sinecure, as you might say. But there's one thing been going on in this town, off and on, that's got to be stopped. Old Rodge has got to be kept from stealing chickens off of Dave Roscoe!"

"Don't see how you're goin' to stop that," said Thad. "Nobody ever knows he's stealin' until he's stole. I ain't got no license to arrest a man until he's done somethin' to arrest him for. I thought of Rodge soon as I got this job, an' I been lookin' through the law, and no marshal can't arrest a man for what he's goin' to steal."

"No, you can't," said Judge Barnabee Holt. "But it won't do you no harm to keep an eye on Rodge, and to let me know when he begins showing signs. By Harry! I'm going to serve out a full term if I have to sit up nights and watch Rodge Williams myself! I ain't going to have him fetched up before me for stealing no chicken off Dave Roscoe. This here job hasn't been nothing but resign, resign, resign, and I ain't going to let Rodge Williams resign me. No, by Harry! I ain't going to have nobody that has cousins and aunts and stepsisters and things oust me out of this office. I don't want nobody like that brung before me at all."

"Well, we don't aim to fetch old Rodge up," said the marshal.

"Fetch him!" exclaimed Judge Holt. "You know as well as I do there ain't been a marshal fetched him for years. Dave Roscoe fetches him. And I don't want him fetched. All I say is, keep a lookout on Rodge and let me know when he begins showing signs. I'll tend to him."

The fourth night thereafter, Thad Carter, sitting on old Rodge's doorstep, awoke at three in the morning and stretched himself.

"Dog take it," he said disgustedly, "this ain't no sort of place for a feller to sleep!" and the next morning he turned in his badge to the mayor and resigned. The oak of old Rodge's doorstep was too hard to make ten dollars a month enticing.

Judge Holt tried his best to get some other citizen to accept the office, but his efforts were unavailing. It seemed, as the days passed, a needless precaution. Old Rodge, for all the signs of lawlessness he showed, might have reformed forever. Each morning at ten he walked down to Galbraith's store, leaning on his cane and proceeding in his leisurely fashion, seated himself on the pine beach facing the hitching rail, and talked war, politics, and weather like an honest citizen. Each noon he walked home, cooked his frugal meal, and walked back. Each evening he walked home, ate his cold supper, and walked back to the store. At ten he got up from the checkerboard, walked home, and went to bed.

The months passed. Judge Barnabee Holt sat behind his table in his office over the Kilo News office and read the Chicago paper line by line. In the afternoon he put his feet on the desk, tilted his chair back, and slept snoringly, his close-clipped, iron-gray beard sticking straight up in the air or brushing his shirt front as his head toppled up or down. Once in a while, at long intervals, he had a case, and his bushy, coarse eyebrows frowned down over his eyes as he laid down the law with his hard fist. But old Rodge remained as sweetly innocent as a babe.

It was close on to a month before the expiration of Judge Holt's term when the marshal came stumping up the stairs and into the justice court, and Judge Holt sat up straight in the middle of a snore.

"Judge," said the marshal, "old Rodge is showin' signs."

"'Y Harry!" cried Judge Barnabee Holt, wide-awake in an instant. "Is he bad?"

"He ain't bad," said the marshal. "He's just begun to start to show signs. I should say he's got about two drinks into him, judge, by the way he looks. He ain't begun onto that story of the mule that et the ammunition yet, but he's high-colored at the top of his cheeks."

Judge Barnabee Holt frowned.

"That's how he starts off looking," he said. "Talking much more than usual?"

"He ain't goin' it hard, yet. Seems like I did notice he was inclined that way. Seems like he interrupted Andy Jackson Harker more'n he usually does. I reckon it'll be to-morrer before he gits real talkative. You said to let you know first off if I see signs."

"You done right," said Judge Holt, and he drew on his coat. "I'll just go down and set a while and see what I think."

His observations as he sat on the bench beside old Rodge were far from comforting. The old man was flushed below the eyes. He was eager to break into the conversation. He cackled more than usual when Andy Jackson Harker told the joke about the corporal who tried to catch the pig. Judge Holt arose from the bench and set out to find Dave Roscoe. He found him in his small lumberyard, loading a farmer's wagon with siding.

"Rodge is showing signs again, Dave," he said.

"Let him show," said Dave. "Long as he lets my poultry alone him and me ain't got no quarrel. If he touches my hens up he goes!"

"Dave," said the judge, "it ain't needed that I should tell you I'd like to be the first J. P. to finish out a term in this town. I've sort of set my mind onto it. It's an ambition I've got."

"That's all right, judge," said Dave. "I ain't got nothin' against that. Long as Rodge leaves my poultry alone --"

"Now, look here," said Judge Holt, and he made Dave a proposition such as had never been made in Kilo before. He offered to buy Dave Roscoe's chickens ; roosters, hens, and chicks. "It's an ambition I've got, to end out my term," he repeated. "I'll buy out your whole poultry yard, and when Rodge gets over his spell I'll sell 'em back to you, same price, less what Rodge takes a mind to want."

"Ain't for sale," said Dave shortly. "That old Rodge has pestered the life out of me, almost, comin' along whenever he takes a notion and stealin' my hens. Ain't a man got any rights in his own hens? Just because a feller knows how to get hold of liquor has he got a right to bust into my coop and go off with my property whenever he wants to? This town makes me mad, it does. Seems I'm the only man in it that can't get justice. I've got to sit around and let a feller come an' steal my hens whenever he takes a notion, and when I try to get law on him everybody goes and resigns. Dumb take you town officers, anyway! All a man has got to do is say 'Rodge!' at you an' you all lope down to the city clerk and resign. I can't get no justice! No, sir, judge, it ain't no use coming to me about Rodge Williams. I don't owe him no hen, and I never did, and he's had about forty hens I never did owe him. I'm goin' to keep on arrestin' him until I can get justice, and that's all there is to it. I'm goin' to see Rodge Williams in jail if I have to live to be a hundred to do it. Yes, dumb take it, if I can't get him jailed no other way I'll turn Demmycrat!"

After such a threat, it was no use bothering with Dave Roscoe. Judge Holt walked slowly up Cross Street and turned into Main. Twice on the short block of Cross Street between Dave Roscoe's and the corner he was stopped. Orley Wiggs stopped him first.

"Hey, judge!" he called from his blacksmith shop. "Judge, they tell me old Rodge is gettin' lit up again. I just want to say a word for him in case he gets a-holt of one of Dave Roscoe's chickens this time. Dave ain't ever had Rodge up before you for chicken stealin', and we don't know how you feel about it, but Rodge is a second cousin to my wife. Feelin' poorly like she does, with the twins just born and all, seems like my wife couldn't stand havin' a relative locked up in the calaboose. The dis-grace might kill her, feelin' poorly like she does."

"I know! I know!" said Judge Holt, and tore himself away. The second to stop him was Wright Cunningham.

"Judge." said Wright, "I just passed by old Rodge up yonder, and he looks sort of curious to me, like he'd found liquor again. It ain't for me to try to interfere with the law, but if you had gone through the war with a feller, and had tented with him, and then he got a notion into his head that some feller owed him a chicken --"

"Yes, yes! I know!" exclaimed Judge Holt. "I understand."

On Main Street, he was not able to walk ten paces without some nephew, cousin, brother-in-law, or comrade of old Rodge drawing him mysteriously aside. Some asked him outright to let old Rodge off if he stole a chicken; some hinted the request, and some merely prepared the way to make the request later. He walked past old Rodge and seated himself on the end of the bench, next to the faithful marshal.

"Has he been drinking any more?" he asked, in an undertone.

"Not a sip," said the marshal. "Hasn't been off'n the bench."

"He looks more het up."

"Well, that's how it works on him, judge. It gits goin' and keeps heatin' him up and heatin' him up. Tonight maybe he'll take a couple of swigs when he goes home, and after supper he won't allow that Joe Wallis plays a straight game of checkers. 'Bout nine o'clock he'll claim a move or two an' git mad if he can't have 'em. Tomorrow mornin' he'll be reddish in the face and begin talkin' about eggs and poultry, and tomorrow afternoon he'll start in tellin' what he thinks of Dave. An' tomorrow night he'll go Plymouth Rockin'."

"Humph!" said the justice. "You come along with me. You come along behind me as if you just happened to." Judge Holt led the way to old Rodge's one-room house. He tried the three windows first and found them securely nailed down. Then he tried the front door and found it unlocked. He went in, and, with the marshal, ransacked the place. Not a drop of liquor was to be found anywhere. He went into the yard and searched almost inch by inch. He had the marshal climb under the house and go over the dusty mold inch by inch. No liquor. No sign of a hiding place.

"Most like he's got it on him," said the marshal at last, as he crawled out from under the house. "If you was to get a-hold of him somehow and search him --"

The justice said nothing. He returned to the business section of Main Street and seated himself on the well-polished bench beside old Rodge. For the rest of the afternoon he sat there observing the old man with anxious eyes. It seemed, as he watched that the symptoms of trouble were lessening. The color under old Rodge's eyes was not as strong; but, on the other hand, old Rodge became nervous as supper time drew near. He fidgeted on the bench, and did not wait until all arose, but left fifteen or twenty minutes earlier. Judge Barnabee Holt left with him, walking at his side.

"Rodge," he said, as they walked up the street, "you've got liquor again."

The culprit did not answer.

"I ain't going to say nothing about a man your age knowing better than to act this way," said Judge Holt. "You know all about that as well as I do. If you don't care enough about yourself to leave red whisky alone nothing I can say is going to help. I ain't going to say nothing about it being a sort of sneak trick, getting whisky on the sly. I ain't going to say nothing about all these relatives and comrades and friends of yours and how it gouges into them when you act this way. You know all that as well as I do, and it never done no good. When you git going you git going, and you don't care a hang."

Old Rodge shuffled along in silence. Perhaps he hung his head a little.

"But, by Harry!" said the justice violently, "I'm not going to have my chance at the State legislature kicked to nothing by you, nor nobody else, Rodge Williams! I've set my mind on going to Des Moines to represent this county, and I'm going to serve out my term as justice whether you go chicken stealing or don't go chicken stealing. For going on twenty years you've turned this law-abiding community into a lawless, law-breaking, crime-reeking place every time you got a notion to steal one of Dave Roscoe's hens, and it has got to stop. There ain't anybody can lie down at one end of the year and feel safe in their beds that before the year is out crime won't be ramping around loose in you and setting you up to stealing one of Dave's hens."

"Now, now, judge --" said Rodge meekly.

"Yes, by Harry, that's what this town has come to!" cried the judge. "There can't anybody take the office of justice without writing out his resignation at the same time. If he gives you the law he makes your whole tribe sore, and if he don't he makes Dave and his whole tribe sore. There ain't no peace for a justice at all, and, by Harry, I'm going to have peace!"

"What -- what you goin' to do, Barnabee?" asked Rodge.

"I'm going to stay right with you," said Judge Holt angrily. "I'm going home with you, and I'm going to be with you all the time. I'm going to eat my meals with you and sleep with you, by Harry! If I have to stick to you to the end of my term, I'm going to do it; but, Rodge Williams, you ain't going to steal no more of Dave Roscoe's hens!"

"Now, Barnabee," said Rodge soothingly. "I don't want to steal none of Dave's hens. Me and Dave fixed that up long ago. Dave don't owe me no hen. I don't like you to talk that way, Barnabee, just as if I had in mind to steal a hen."

The justice shut up like a clam. What could he say to a man who talked like that?

Old Rodge accepted the attentions of the justice with the meek resignation of one who is maligned and oppressed, but who is forcing, himself to make no complaint. For a week Judge Barnabee Holt clung to old Rodge like a shadow. The high color faded out of old Rodge's face; no search of the old man's garments revealed liquor; but still Judge Holt clung to him.

Dave Roscoe was, during this time, particularly unpleasant. Whenever he could leave his coal-and-wood business he sought out Judge Holt and warned him that as soon as old Rodge stole a hen justice would be demanded in the fullest.

"I'm tired and sick of havin' a man -- just because he's related all over the county -- make free with my propputty. Law is law, and I'm goin' to have it."

Perhaps the continued loss of hens had at length afflicted his temper. He was downright mean about it.

The dreaded event occurred one Tuesday night. A tramp had wandered into town that day, and Judge Holt had been obliged to open his office and decide whether the tramp had taken a pair of socks from Mrs. Cunningham's back porch while she went inside to get him a few slices of bread, and when the justice returned to old Rodge there were unmistakable signs of a falling from temperance. Old Rodge's color was high, and his tongue was loosened. He had told the story of the mule that ate the ammunition three times in succession, and was trying to tell it the fourth. He even greeted the justice, for whom he had begun to have an unaccountable distaste, jovially.

That night Justice Holt prepared to spend sleeplessly. He seated himself in a stiff-backed chair and sat watching old Rodge breathe heavily in his bed, but for more than a week the justice had lost his afternoon naps, and presently his bearded chin fell upon his breast, and old Rodge opened one sly eye and surveyed his keeper. Very cautiously, as Justice Holt's head swayed from side to side, old Rodge slid out of bed and drew on his trousers. He tiptoed to the door, opened it, and slipped out.

When Judge Holt awakened, with a gulp and a start, old Rodge's bed was empty. He ran from the house and collided with Dave Roscoe.

"Here!" said Dave, with all the anger of which his voice was capable. "Here he is! Here's the dumb-took chicken thief. And here's the hen I found onto him."

Old Rodge cackled in a silly manner. He was in no state to appreciate the gravity of his act. He stumbled as Dave released him, and would have fallen over the doorstep had Judge Holt not caught him in his arms.

"Dave," said the justice, "can't this be fixed up?"

"No, it can't!" said Mr. Roscoe promptly. "The only way this can be fixed up is for this chicken thief to spend time in the county jail down to Jefferson. For years and years my rights has been walked onto, and my hencoop has been violated into, and nobody would give me justice, and now I'm goin' to have it. This can't be fixed up at all except one way. You got to hold court onto him and give him a term. I don't care if he goes to the penitentiary. Nothin' can't be fixed up with me. Do you want I should wake up the marshal and turn him over to him?"

"You can leave him with me," said Justice Holt.

"No, I can't leave him with you, neither," said Dave nastily. "I can't leave him with you to have you let him go and hustle him out of the county. I can sit right here with him until the marshal comes down to open the calaboose."

And that was what he did. He sat on the doorstep, first making sure the back door was fitted with a lock and that the key was in his own pocket. Judge Holt walked the narrow confines of the room, thinking, thinking, thinking! He had already sat upon the justice's bench longer than any of his immediate predecessors; a few weeks more and he would have served out his term. As the sun brightened the room and made the lamp flame turn dull yellow, he sighed. He looked at the pitiful old man on the bed and shook his head.

Judge Barnabee Holt left Dave in charge when he walked to Higgins Lane to notify the marshal there was a prisoner awaiting him. He went home from there and ate his breakfast, answering his daughter gruffly when she expressed surprise that he had come home. When he walked downtown, the news that old Rodge had been chicken stealing again was abroad, and one after another of old Rodge's friends, comrades, and closer connections stopped him with the usual pleas for mercy. It was well toward noon when the justice, his face drawn, entered his courtroom and locked the door.

He took the best of the three pens that lay in the glass tray on his table, drew a sheet of paper from the drawer, and wrote his resignation. There was no other way out of the difficulty. His ambition had collided with the rock against which the ambitions of all his predecessors had been shattered, and there was no escape. Between Dave Roscoe, demanding the full penalty of the law, and old Rodge's host of supporters demanding his vindication, Justice Holt had been driven on the rock. He read his resignation through the second time, dipped his pen in the ink, and signed it. Then he unlocked his door and waited. There was one chance old Rodge might die before he was haled into court. It was as slim a chance as ever a man had.

He sat with his head bowed, and did not raise his head as he heard heavy feet clumping up the stairs.

"Judge!" said a voice at his door.

"Now, don't begin all that again!" cried Judge Barnabee Holt, in a rage. "It's no use, Dave Roscoe. I've heard you say it a hundred times, and --"

"Now, judge, just be patient," said Dave meekly. "Just wait until you are hurt, can't you? I just want to say one ward. I just want you to read this letter."

The justice reached out a listless hand and took the letter. He read it through and turned it over and looked at the back. It was dated Los Angeles.

"Well, what about it?" he asked.

"I got it out of the post office this morning, judge," said Dave. "You take note what it says about a wedding there? Sarah and Jim, it says. Well, Sarah is my wife's cousin's second daughter, and this Jim is old Rodge's first wife's niece's oldest boy, and I come up here to ask you to let old Rodge off. Being related to him that way, it would be a disgrace to my family to have him in jail. I don't ask many favors of you, but if you can let old Rodge go this time --"

"The law says --" began Judge Barnabee Holt.

"Says something about chicken stealing, hey?" said Dave. "Well, who's been stealin' chickens? Nobody!"

"Are you sure?" asked Justice Holt eagerly.

"Sure?" said Dave Roscoe. "Sure? Ain't I just showed you old Rodge had sort of married into my family? Ain't he comin' over to my house to dinner to eat chicken? Of course I'm sure!"

"I don't see that I can grant you any favor, Dave," said the justice gravely. "There don't seem to be any case against Rodge Williams onto my docket."

"I'm mighty glad to hear it," said Dave heartily, and Judge Barnabee Holt was permitted to serve out his term.