from Century Magazine

Mr. Wellaway's Host

by Ellis Parker Butler

I

"No, sir," said Mr. Wellaway, positively, "this is not the club at all. This is not the sort of club. The club I mean has a heavier head -- heavier and flatter."

The clerk looked here and there among the racks of golf clubs, but his general manner was that of hopelessness. There seemed to be thousands of golf clubs in the racks, and he had shown Mr. Wellaway club after club, each seeming to fit the description Mr. Wellaway had given, but in vain. Mr. Wellaway looked up and clown the shop.

"If I could remember the name of the clerk," he said, "he would know the club. He sold one of them to Mr. --" He hesitated. "Now I can't remember his name. A rather large man with a smooth face. He has a small wart or a wen just at the side of his nose. You didn't wait on such a man last week, did you?"

"I can't recall him by the description," said the clerk.

"Pshaw, now!" said Mr. Wellaway, with vexation. "I know his name as well as I know my own! I would forget my own if people didn't mention it to me once in a while. It is peculiar how a man can remember faces and forget names, isn't it?"

"Yes, it is," said the clerk. "If you just look through these clubs yourself, you may be able to find what you want. Was the name of the clerk you had in mind, Mills? Or Waterson? Or Frazer?"

"It might be Frazer," said Mr. Wellaway, doubtfully.

"If it was Frazer," said the clerk, "he left here last Saturday."

"But couldn't you look up Frazer's sales and see what kind of driver he sold? But of course you can't if I don't remember the name of the man he sold it to, can you?"

"Not very well," admitted the clerk, with a polite smile. "Now, if you like a heavy club --"

He was interrupted by another customer. The golf goods were on the basement floor, and a short flight of steps led to the basement from the main floor, and the new customer had come down the stairs. He was a big, bluff, hearty man, with a cheerful manner and a rather red face, and Mr. Wellaway immediately remembered having met him sometime and somewhere. He nodded his head with the ready comradeship of a fellow golfer.

"Hello!" exclaimed the newcomer, heartily. "Well! Well! So you are at it too, are you? Got the golf fever?" Then to the clerk: "Got my brassy mended?"

"What name, sir?" asked the clerk.

"Didn't leave any name," said the big man. "It's a mahogany brassy, the only real mahogany brassy you ever saw. I had it made to order," he said to Mr. Wellaway, as the clerk hurried away to the repair department. "So you've taken up golf, have you? It's a great game."

"It is a great game," said Mr. Wellaway; "but I've been at it a long time. Not that I'm much good at it."

"No one is ever any good at it except the crack players," said the other. "I'm as bad as they make 'em; but I love it. Where do you play?"

"Van Cortlandt," said Mr. Wellaway.

"Ever play Westcote?"

"No," said Mr. Wellaway. "I've been in the village, but I didn't know there was a course there."

"Best little course you ever saw," said the hearty man. "Nine holes, but all beauties. I want you to play it sometime. Look here," he added suddenly, "what have you got on for this afternoon?"

"Well, I was going up to Van Cortlandt," said Mr. Wellaway, hesitatingly.

"That's all off now! You're coming out with me and have a try at our Westcote course. Yes, you are. You know I never take 'No' for an answer when I make up my mind. And, look here, we have just time to get a train."

Mr. Wellaway's host beckoned violently to the clerk.

"But my clubs --" protested Mr. Wellaway.

"That's all right, too. Our professional can fit you out."

"I ought to telephone my wife."

"Oh, do it from the club."

The temptation was too much for Mr. Wellaway. It was a hot day, and he knew the public links at Van Cortlandt would be crowded to the limit. He imagined the cool green of the little course at Westcote and let himself be persuaded, and in four minutes he was aboard the commuters' train, being whirled under the East River.

It was not until the train was out of the tunnel and speeding along over the Long Island right of way that he felt the first qualm of uneasiness; but it was a very slight qualm. He was ashamed that he could not remember the name of his host. The man's face was certainly familiar enough, and the man evidently knew Mr. Wellaway well enough to invite him to play golf, or Mr. Wellaway would not have been invited; but the name would not make itself known. But, after all, that was an easily remedied matter. The first friend they met would call Mr. Wellaway's host by name.

At Woodside they left the electric train and boarded the steam train, but no one had spoken to Mr. Wellaway's host on the platform. One or two men had nodded to him in a manner that showed they liked him, but none mentioned his name. Mr. Wellaway smiled. He would use a little very simple Sherlock Holmes work when the conductor came through for the fares.

Mr. Wellaway had noticed that his host used a fifty-trip ticket book when the conductor asked for the fare on the electric, and now he waited until the new conductor tore the trip leaves from the book and returned the book to its owner.

"I see you use a book," said Mr. Wellaway. "Do you find it cheaper than buying mileage?"

He held out his hand for the book. It was an ordinary gesture of curiosity, and his host surrendered the book.

"No, I don't, not usually," he said. "And a commutation ticket is cheaper than either. Now, a commutation ticket costs --"

He entered into the commuter's usual closely computed average of cost per trip, and Mr. Wellaway nodded his acquiescence in the figures; but his mind was elsewhere. He read as though interested the face of the book, and then turned it over. There on the back, in a bold hand, under the contract the thrifty railroads make book holders sign, was the signature, "Geo. P. Garris." Mr. Wellaway stared at the name while he ransacked his memory to recall a George P. Garris. He not only could not recall a George P. Garris, but he could not remember ever having heard or seen the name of Garris. If the second "r" was meant for a "v," the name might be "Garvis," but that did not help. He could not recall a Garvis. At any rate, it was some satisfaction to know his host was George P. Garris or George P. Garvis. When and how he had met him would probably soon appear.

"I see you are looking at that name," said Mr. Wellaway's host, "and I don't wonder. Matter of fact, I have no business to have that book; but Garvis was a good fellow, and he needed the money, so I bought it off him when he left Westcote."

"Oh," said Mr. Wellaway, blankly, and then: "So that's why you are not using a commutation ticket this month." He had to say something.

"That's the reason," said his host; "and this is Westcote."

II

The Westcote Country Club was all Mr. Wellaway's host had boasted. The greens rolled away from the small clubhouse in graceful beauty, small groves of elms and maples studded the course, and picturesque stone walls and sodded bunkers provided sufficient hazards. Everything was as neat as a new pin. It was a sight to make any golfer happy, but when the station cab rolled up to the clubhouse door, Mr. Wellaway was not entirely happy. He was beginning to feel like an interloper. The more he studied the face of his host, the surer he became that he had no business to be a guest. As a word in print, when studied intensely, becomes a mere jumble of meaningless letters, so the face of his host grew less and less familiar, until Mr. Wellaway had decided his familiarity was with the type of face and not with this particular face. One thing alone comforted him: his host seemed to know Mr. Wellaway.

As they left the cab, Mr. Wellaway made a desperate effort to learn the name of his host; for he felt that if he did not learn it now he was in for a most unpleasant five minutes. Mr. Wellaway was a small, gentle little man, but he was almost rude in his insistence that he be permitted to pay the cabby.

"Yes, I will," he insisted. "I certainly will. If you don't let me, I'll be downright angry. You paid my fare, and you offer me an afternoon's sport; but I am going to pay this cabman."

"But this is my party," said his host.

"You go right into the clubhouse, and let me pay," said Mr. Wellaway. "I want to do this, and you ought to let me." With a laugh the host turned away. Mr. Wellaway fumbled in his pocket until he was alone with the cabman.

"What is the charge?" he asked.

"Quarter," said the cabby, briefly.

"Here's a dollar," said Mr. Wellaway. "Now, can you tell me the name of that man -- the man who drove up with me?"

"No, sir," said the cabman; "I don't know what his name is."

"I just wanted to know," said Mr. Wellaway.

When he entered the clubhouse his host was alone.

"You wanted to telephone," he said to Mr. Wellaway. "There's the booth. It's a money-in-the-slot machine. I'll get a greens ticket and a bag of clubs for you while you are in there, and we will not lose any time. When you come out, come up to the locker room."

Mr. Wellaway entered the booth and closed the door. He called for his number and waited while the connection was made. It was hot in the booth with the door closed, but not for the world would Mr. Wellaway have opened it.

"Hello, is that you, Mary?" he asked, when he had dropped the requisite coins in the slot at the request of the central. "This is Edgar. Yes. I'm out at Westcote, on Long Island. I'm going to play golf. I met a friend, and he insisted that I come out here and try his course. I say I met a friend. Yes, a friend. An old acquaintance. He lives out here."

For a few seconds Mr. Wellaway listened.

"No, listen!" said Mr. Wellaway. "I don't know what his name is, but I'll find out. I just met him, you know, and he asked me, and I couldn't say, 'Thank you, I'll accept; but what is your name?' I couldn't say that, could I? When he knew me so well? Oh, nonsense, Mary! I tell you it's a man."

As he listened to what Mary had to say to this, Mr. Wellaway sighed deeply.

"No, it is not funny that I don't know his name," he said. "You know I can't remember names, and I know thousands of men, and speak to them, and can't recall their names. Listen! There's no reason in the world for your jealousy to get stirred up. Not the least. I'll know his name inside half an hour, and if you are going to act that way about it, I'll telephone you the minute I learn it. Yes, I will! Well, that's all right, too; but since you take that attitude, I'm going to telephone you. Goodbye." He waited half a minute for an answering "Goodbye," and then hung up the receiver softly. Mary's jealousy was a real annoyance. Mr. Wellaway stepped out of the booth and wiped his forehead.

The small sitting room of the club was deserted. In the adjacent butler's pantry he could hear the steward at work, and above the low ceiling he could hear his host changing his shoes. On the bulletin board, among the announcements of competitions and new rules, was a list of members posted for dues or house accounts. It was a very short list, and Mr. Wellaway recognized none of the names. On the opposite wall was a framed list of the club members, perhaps one hundred and twenty-five, and Mr. Wellaway ran his eye down them. Only one of the names was familiar, that of George C. Rogers, and the host was not Rogers, for Mr. Wellaway knew Rogers well. Not another name was even faintly familiar. Mr. Wellaway was still poring over the list when his host descended the stairs.

"I see," said Mr. Wellaway, "that George Rogers is a member of the club."

"That so?" said his host. "I don't know him. I don't know many of the fellows yet. Rankin and Mallows are putting me up for membership, but I'm playing on a temporary card until the next meeting of the board of governors. They say there's no doubt I'll be admitted; but I don't take chances. I pay as I go until I'm a full member. When I'm in, I'll sign checks like the rest of them; but until I am in, I'll pay cash. Now, you run up and shuck your coat, if you want to, while I get you a bag of clubs and a greens ticket. I left my locker open -- Number 43."

Mr. Wellaway ascended the stairs. All about the locker room were the lockers, two high, and on each was the name of the holder. The door of 43 stood open, and Mr. Wellaway darted for it, and looked for the name of his host. There was no name on the locker.

III

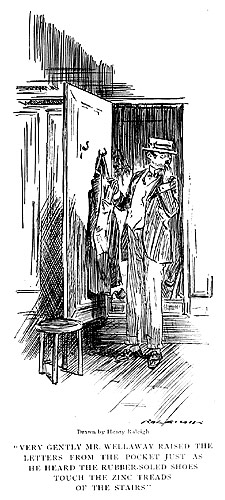

In the locker was the usual accumulation of golfer's odds and ends. A few badly scarred golf balls lay on the floor, along with a pair of winter golf shoes. A couple of extra clubs stood in one corner. A sweater hung from a hook, and from another hook hung the coat and waistcoat his host had just removed. From one pocket, the inside pocket, of the coat protruded the tops of three or four letters. Mr. Wellaway stared at the letters and perspired profusely. He had only to put out his hand and raise the letters partly from the pocket to know the name of his host. Then he could make an excuse to telephone his wife again. Assuredly there was nothing dishonorable in merely glancing at the address of the letters. But he stood very still and listened intently before he put out his hand. He could hear the soft tread of rubber-soled shoes on the floor below. Very gently Mr. Wellaway raised the letters from the pocket just as he heard the rubber-soled shoes touch the zinc treads of the stairs. He slid the letters back into the pocket in a panic, and jerked off his coat, but he had seen the address of the outermost letter. It was an unmailed letter, and it was addressed to "Mrs. Edgar Wellaway, Rimmon Apartments, West End Avenue, New York."

"All ready!" said his host, cheerfully.

"Just a moment," said Mr. Wellaway. He was taking his papers from his coat pockets and putting them in the hip pocket of his trousers. A man cannot be too careful.

IV

Mr. Wellaway's host used a Scotch-plaid golf bag, without initials painted on it, and when the two men issued from the clubhouse the bag was leaning against the wall immediately under the outside bulletin board. One list on the board was headed "Applications for Membership," but there were no names entered later than a month and a half old, and all these had the word "Elected" written after them. When Mr. Wellaway caught sight of the other list his face brightened.

"My handicap is eighteen," he said, looking through the list of members with the handicaps set opposite the names.

"Two better than mine," said his host. "I play at twenty."

"Twenty?" said Mr. Wellaway, running his finger up and down the handicap list.

"But I haven't been given a handicap here yet," said his host. "They don't give you a handicap here until you are a member."

"Oh," said Mr. Wellaway, and turned away. He had no further interest in the handicap list.

The course was clear for the entire first hole. Mr. Wellaway got away with a clean drive, but sliced his second into the rough, while his host sliced his first into a sandpit, got out with a high niblick shot, and lay on the putting green in three.

Mr. Wellaway wasted a stroke chopping out of the rough, and put his ball on the green with a clean iron shot in four, close enough to putt out in one, making the hole a five. His host took two to hole out, doing another five, but winning the hole on his handicap, which gave him one stroke on the first hole. It was good golf, par golf, and Mr. Wellaway was elated. To do a hole in par on a strange course, after getting into the rough, was better golf than he knew how to play, and the loss of the hole after such playing made him only the more eager to play his best. He forgot Mary's jealousy and his annoyance at not knowing the name of his host, and played golf as he had never played it before. The professional's clubs seemed to work magic in his hands. At the ninth hole he was still one down, but his host did the first hole on the second round in eight, to Mr. Wellaway's seven, and it was seesaw around the course the second time, with all even when eighteen holes had been played.

"I guess we can play it off before the storm hits us," said Mr. Wellaway's host, and for the first time Mr. Wellaway noticed the black clouds piling up in the west. They started the nineteenth hole with a rush of wind whirling the dust from the road across the course, and before they had walked to where their balls lay after their drives, the forward edge of the storm clouds, low, ragged, and an ugly yellow, was full over them, and a glare of lightning, followed by a tremendous crash, blinded them both. Mr. Wellaway's host threw his bag of clubs on the grass as though it were red hot, and started at a full run for the clubhouse. Mr. Wellaway followed him.

Except for the steward and his wife, the clubhouse was already deserted, the last automobile tearing down the club roadway as Mr. Wellaway reached the veranda. The lightning exceeded anything Mr. Wellaway had ever seen, and crash followed crash in deafening explosions, as though the electrical storm had centered near the clubhouse. A fair-sized hickory tree, half dead from the depredations of the hickory bark beetle, fell crashing across the sleeping room annex of the clubhouse. For half an hour after the rain began to fall in sheets the lightning continued, while Mr. Wellaway and his host stared at the storm through the windows of the clubhouse; but about six o'clock the worst of the storm had passed on, and the rain had become a steady, heavy downpour.

"There's one thing sure," said Mr. Wellaway's host: "there's no going home for you tonight."

"But I must go home," said Mr. Well away.

"If you must, of course you must," said his host; "but there would be no sense in going in this rain. We will have dinner right here. I suppose you can get us up a couple of chops or something?"

"Yes, sir," said the steward, who had returned from a survey of his sleeping quarters. "Chops or steak."

"Then I'll just phone my wife that I'll not be home," said Mr. Wellaway's host, and he entered the telephone booth. In a few minutes he came out again. "Can't get central," he said with annoyance. "The thing is either cut off or burned out. Probably a tree has fallen across the wires. I hate to drag you out through all this rain, but my wife will be distracted if I don't get home. She'll imagine I'm killed. You will have to come home with me and take pot luck."

"Why, that's very kind of you," said Mr. Wellaway, "but I could not think of it. My own wife will be worrying. I'll just scoot through the rain to the station and get the first train home."

"Of course, if you think best," said the host. "We have to pass the station on the way to my house. But Sarah would be glad to put you up for the night."

The station was not as far as Mr. Wellaway had feared, for it was not necessary to walk to the main station; there was another nearer, and they reached it a few minutes before a train for the city was due. Mr. Wellaway's host walked to the ticket window.

"I presume the train is late," he asked.

"You presume exactly right," said the young man in the ticket office. "She's not only late, but she's going to be later before she ever gets to New York. The lightning struck the Bloom Street bridge, and the bridge went up like fireworks. It will be about twenty-four hours before anybody from this town gets to New York."

"Twenty-four hours!" exclaimed Mr. Wellaway, aghast. "But I can telegraph."

"If you can, you can do more than I can do," said the young man. "I've tried, and I can't do it, and I'm a professional."

"Well!" said Mr. Wellaway.

"All right," said his host. "Now there's nothing for you to do but accept my invitation, and I make it doubly warm, Sarah will be delighted. You are the first guest we've had for the night since we moved out here. She'll be delighted, I tell you. And so will I."

"But I ought to go home," insisted Mr. Wellaway.

"But you can't go home," laughed his host. "Come right along. Sarah will be delighted. She's -- she's fond of company. Perhaps our phone will be working. You can telephone your wife from our house. Really, Sarah will be glad -- she'll be delighted, I tell you."

So Mr. Wellaway accompanied his host. The house to which he was led was an average suburban dwelling, a frame house of ample size, with wide verandas, a goodly lawn, and the usual clumps of shrubbery. At the screen door the host paused.

"If you don't mind," he said, "I'll let you wait here while I step inside and tell Sarah we are coming. Sarah is the most hospitable of women, and that's the reason I want to tell her. She'll welcome you with open arms, but -- you know how these hospitable women are, don't you? They like a minute or two to get into a more than casual mood. It will be all right. Only a minute."

"Certainly," said Mr. Wellaway, feeling rather uncomfortable, and his host opened the door with a latchkey and entered. If Mr. Wellaway could have heard what passed inside that door, he would have turned and run.

"Darling!" exclaimed his host's wife when she saw him. "How wet you are! Go right upstairs and get into a hot bath this minute! You'll die of cold!"

"In a minute, Sarah," said her husband; "but, first, I've got a man out there. He's going to stay for dinner and sleep here."

"Oh!" exclaimed Sarah, letting her mind jump to her larder. "But we didn't expect any one. Really I don't know. Perhaps I can make what I have do. Is -- is it any one important?"

"Don't know," said Mr. Wellaway's host, hastily. "I'll tell you all about it when I'm dressing. I don't know the fellow's name, but he knows me as well as I know you. I ought to know his name as well as I know yours, but I don't. I met him somewhere, and I remember he was a good fellow. We'll get his name out of him somehow before he's in the house very long, but, for Heaven's sake! Don't let him know I don't know. He may be some one important. He looks as if he might be somebody. I'll bring him in. Don't give me away."

"But you don't know who he is. He may be a thief --"

"Hope not. I can't let him stand out there any longer, anyway. Be pleasant to him."

He threw open the door.

"Come right in!" he exclaimed heartily. "I've bearded the lioness, and told her the story of our lives. I don't believe you have met before."

"I have not had that pleasure," said Mr. Wellaway, making his best bow, "but I am delighted, although I'm sorry to come unannounced."

"Announced or unannounced, you might know you are always welcome," said Sarah, charmingly. "And the first thing is to get on some dry clothes. You'll both of you take cold. Run along, and I'll see what we have for dinner."

The garments given him by his host did not fit Mr. Wellaway specially well. They were considerably too large, but he was glad to get into anything dry. What dissatisfied him with them more than aught else was that they were the sort of garments of which the newspapers remark, "There were no marks of identification." The spare room into which he was put offered no more aid. Three or four recent magazines lay on the small table, but bore no names except their own titles. For the rest, the spare room was evidently a brand new spare room, fresh from the maker. For purposes of identification it might as well have been a hotel bedroom. Mr. Wellaway dressed hastily and hurried downstairs.

The parlor, to the right of the stairs, stood open, and Mr. Wellaway entered. A large fireplace occupied one end of the room, and the furnishings and pictures bespoke a home of fair means, but no great wealth. Magazines lay on a console table, but what attracted Mr. Wellaway was a bookcase. The case was well filled with books, in good bindings, and Mr. Wellaway stepped happily across the carpet and laid his hand on the bookcase door. It was locked.

V

Mr. Wellaway's host and his host's wife descended the stairs together just as the maid issued from the dining room to announce dinner, and once seated, the conversation turned to the storm, to the utter disruption of the telephone service, and to the game of golf the two men had been unable to finish. In the midst of the conversation Mr. Wellaway studied the monogram on the handles of his fork and spoon. It was one of those triumphs of monogrammery that are so beautiful as to be absolutely illegible. The name on the butter knife handle was legible, however. It was "Sarah."

The soup had been consumed, and the roast carved when Mr. Wellaway's host looked at his wife and raised his eyebrows. She smiled in acknowledgment of the signal.

"Don't you think some names are supremely odd?" she asked Mr. Wellaway. "My husband was telling me of one that came under his notice today. What was it, dear?"

"Oh, I shouldn't have noticed it but for the circumstances," said Mr. Wellaway's host; "but it was a rather ridiculous name for a human being. Can you imagine any one carrying around the name of Wellaway?"

Mr. Wellaway gasped.

"Imagine being a Wellaway!" said Sarah. "Isn't it an inhospitable name? It seems to suggest 'Goodbye; I'm glad you're gone.' Doesn't it?"

"I can see the man with my mind's eye," said Mr. Wellaway's host. "A tall, thin fellow, with sandy sideburns. Probably a floorwalker in some shop, with a perpetual smile."

"But tell him the rest," said Sarah, chuckling.

"Oh, the rest -- that's too funny!" said Mr. Wellaway's host. "I had a letter this morning from this Mrs. Wellaway --"

Mr. Wellaway turned very red and moved uneasily in his chair.

"I ought to tell you that -- that I know Mrs. Wellaway," he stammered. "I -- I know her quite well. In fact --"

"Then you'll appreciate this," said his host, merrily. "You know the business I'm in. Every one knows it. So you can imagine how I laughed when I read this letter."

From the inside pocket of his coat Mr. Wellaway's host took a letter. He removed the envelope and placed it on the table, address down.

"Listen to this," he said: "'Dear Sir: Only the greatest anguish of mind induces me to write to you and ask your assistance. It may be that I am the victim of an insane jealousy, but I fear the explanation is not so innocent. I distrust my husband, and anything is better than the pangs of uncertainty I now suffer. If your time is not entirely taken, I wish, therefore, to engage you to make certain that my fears are baseless or well founded. Please consider the matter as most confidential, for I am only addressing you because I know that when a matter is put in your hands it never receives the slightest publicity. Yours truly, Mrs. Edgar Wellaway.' "

When he had read the letter, Mr. Wellaway's host lay back in his chair and laughed until the tears ran from his eyes, and his wife joined him, and their joy was so great they did not notice that Mr. Wellaway turned from red to white and choked on the bit of food he had attempted to swallow. When they observed him, he was rapidly turning purple, and with one accord they sprang from their chairs and began thumping him vigorously on the back. In a minute they had thumped so vigorously that Mr. Wellaway was pushing them away with his hands. He was still gasping for breath when they half led, half carried him to the parlor and laid him on a lounge.

"By George!" said his host, self-accusingly, "I shouldn't have read you that letter. But I didn't know you would think it so funny as all that. Do you feel all right now?"

"I feel -- I feel --" gasped Mr. Wellaway. He could not express his feelings. "Well, it was funny, writing that to me, of all people, wasn't it?" said Mr. Wellaway's host. "'Not the slightest publicity.' I suppose she looked up the name in the telephone directory, and got the wrong address. I know the fellow she was writing to. Same name as mine. Same middle initial. Think you can finish that dinner now?"

"No, thank you," said Mr. Wellaway. "I think I'd like to rest here."

"Just as you wish," said his host. "Hello! There's the telephone bell. You can phone your wife now, if you wish."

"No, thank you," said Mr. Wellaway, meekly. "I'll not. It's of no importance -- no importance whatever."

VI

"Well, what do you think!" exclaimed Mr. Wellaway's host's wife a few minutes later, as she entered the parlor. "Of all the remarkable things! You would never guess it. Who do you think just called me on the phone? That Mrs. Wellaway!"

"No!" exclaimed Mr. Wellaway's host, and Mr. Wellaway sat straight up on the lounge.

"But she did," said Sarah, "And she's hunting that distrusted husband! She telephoned the country club, and the steward told her there had been no strangers there except your guest, so she telephoned here! Imagine the assurance of the --"

She stopped short and stared at Mr. Wellaway. He was going through all the symptoms of intense pain accompanied by loss of intelligence. Then he asked feebly,

"What -- what did you tell her?"

"I told her he wasn't here, and hadn't been here, of course," said Mr. Wellaway's hostess, "and that we did not know any such man, and that I didn't believe he had come to Westcote at all, and that if I had a husband I couldn't trust, I'd keep better track of him than she did."

"Did you -- did you tell her all that?" asked Mr. Wellaway with anguish.

They stared at him in dismay.

"See here," said his host, suddenly, "are you Mr. Wellaway?"

For answer Mr. Wellaway dropped back on the lounge and covered his face with his hands.

"Now, I'll never, never be able to make Mary believe I was here," he said, and then he groaned miserably.

"Oh, I'm so sorry!" said Mr. Wellaway's hostess in real distress. "We were absolutely unaware, Mr. Wellaway. We meant no harm. Roger did not know your name. But you can fix it all right. You can telephone Mrs. Wellaway that you are here. Telephone her immediately."

"Yes," said Mr. Wellaway. "I'll do that. That's what I must do," and he went up the stairs to the telephone. He returned in ten minutes and found his host and hostess sitting opposite each other, staring at each other with sober faces. They looked at him eagerly as he entered. His face showed no relief.

"She says," he said, "she says she don't believe I'm here. She says I could telephone from anywhere, and say I was anywhere else. She says she just telephoned here, and knows I'm not here. And then she asked me where I was telephoning from, and --"

Mr. Wellaway broke down and hid his face in his hands.

"And I didn't know where I was telephoning from!" he moaned. "I didn't know the street or the house number, or -- or the name!"

"You didn't know the name!" cried Mr. Wellaway's host. "You didn't know my name was Murchison?"

"Murchison?" said Mr. Wellaway, blankly. "Not the -- not the Murchison? Not Roger P. Murchison, the advertising agent, the publicity man?"

"Of course," said Mr. Wellaway's host. For a full minute Mr. Wellaway stared at Mr. Murchison.

"I know," said Mr. Wellaway. "You eat at the Fifth Avenue! You sit by the palm just to the left of the third window every noon."

"By George!" exclaimed Mr. Murchison. "I knew your face was familiar. And you sit at the end table right by the first window. Why, I've seen you there every day for a year."

"Of course you have," said Mr. Wellaway, cheerfully. "That explains everything. It makes it all as simple as --" His face fell suddenly. "But it doesn't make it any easier about Mary."

Mr. Murchison might have said that Mary was none of his concern, but he creased his brow in thought.

"Sarah," he said at length, "run upstairs and telephone Mrs. Wellaway that her husband is here. Tell her he means to stay over Sunday, and that he wants her to hire a taxicab and come out immediately and stay over Sunday. Tell her our game of golf was a tie, and I insist that Mr. Wellaway play off the tie tomorrow afternoon."

Mrs. Murchison disappeared.

"And now," said Mr. Murchison, genially, "you know my name, and you know my business, and I know your name, and everything is all right, and I'm mighty glad to know you as long as you are not a floorwalker. Oh, pardon me!" he added quickly, "you are not a floorwalker, are you? You didn't say what your business was."

Mr. Wellaway blushed.

"Names," he said. "I'm a genealogist. My business is looking up names."