from Laughter

Here Comes the Groom

by Ellis Parker Butler

Now, no one need try to tell me a college education isn't a good thing. I mean when it comes to speeding up the old brain-sports and that sort of thing. The rest of it does help some -- Latin and all that junk -- because now and then a man does have to do some quick thinking when a Prof fires a sudden question at him. But what I mean is sports, because, after all, sports is the backbone of the good old college business. When it comes to sports the old head has to be bright and peppy all the while and right up on its toes. The dear old bean has to be ready to be up and doing any moment because there's no telling when some goof will fumble the ball, and a dash of this lightning cerebration stuff may mean a touchdown and three rousing cheers.

I thought this line of thought every time Dad yelped when I stuck the harpoon into him for more cash. And he was wrong, for what can a man get out of college with a mere three thou. a year to pep up the old brain? That's silly talk, if you get me. A man can't get something for nothing these days, and Dad knew as well as I did that he was keen for me to be in things and make the Green Lizard, and this and that team and what not. Which takes cash; anybody can tell you. And when you come right down to it the money was a good investment. Here I am, as you can see for yourself, right in the office of Brace & Bradley, dragging in my little old five thou. a year, right hop-skip out of college, and it was Dad himself told me once he considered me a total loss and no insurance.

Peppy thinking is what did it, lads, and I'm ready to give full credit to dear old Yarvard, where I learned to think fast and act fast, co-ordinate the thought and the act, if you understand me. And here is how it happened, rallying around dear old Tubby's pants, so to speak --

Anyway I look at it I consider the affair a perfect piece of snappy brain work, as I think none will deny, because here is the situation: At eight-thirty on the dot old Tubby is supposed to be standing at the rose-embowered altar with the Reverend Wilson looming near, and myself right there feeling to make sure the ring was in my vest pocket, and the organist pumping out "Here Comes the Bride." Up the aisle is coming the bridal procession -- ushers and flower girls and bridesmaids, and Pop Carter with Dorothy on his arm, and she, the sweetest thing in town, with her shower bouquet and satin dress and veil -- and it is eight-thirty on the tick of the watch. The little stone church is filled to the last seat -- all the real folks and the family connections. That is what is supposed to be happening at eight-thirty sharp at Tubby's wedding. And at eight o'clock dear old Tubby is in my room, one mile from the church, thirty-seven miles out on Long Island, the limousine panting by the veranda, and he has no pants. There he is, sweating like a porpoise, red in the face and garbed in patent leather shoes, black silk socks, pale blue garters, neat but not gaudy underwear, stiff bosom shirt, choker collar, white tie -- and no pants. And there am I, all dolled up like a lounge lizard, turning to him and saying, "Holy smoke, Tubby! Didn't you bring any pants?"

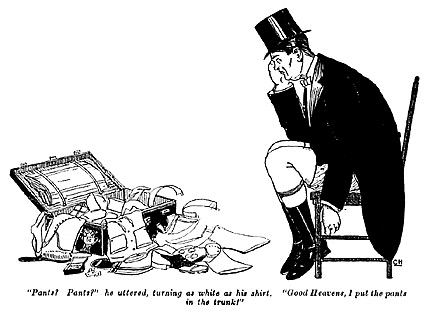

"Pants? Pants?" he uttered, turning as white as his shirt. "Good heavens, I put the pants in the trunk!"

That had been one of his last-moment brilliant ideas. Coming on from Cleveland, as he had, it had seemed to him better to send his trunk direct to the steamer. Thinking it over he had decided that he did not know enough about train connections from Shady Valley to New York and had better risk only hand baggage that could be yanked along with him. So he sent the trunk to the steamer. And that's one thing a man who is getting married should always remember -- never change the mind after it has once been made up. It is too risky; the old brain is apt to be all fussed up and not cerebrate normally. This is so generally recognized by authorities that the groom is usually considered incompetent, irrelevant and immaterial, and the best man is created to look after him and see that he does not, in his excitement and nit-witted condition, nervously swallow the ring, chew up the wedding journey tickets and marry the wrong girl at the last minute. But how, I ask you, was I to know that old Tubby had left his black pants in Cleveland? I distinctly asked him, a full day ahead of time, if he was all set in the clothes matter, and we went over his things together, nosing out white gloves, shirt studs, patent leathers and one thing and another, I checking them up on a list I had made out in my usual businesslike manner, for which I was justly famous at dear old Yarvard. I distinctly remember pointing a finger at the coat hanger in the closet in Tubby's room and saying, "One dress suit," and making a check mark before that item on the list. How was I to know the pants were in Cleveland?

But the moment I learned that Tubby's pants were A. W. O. L. I knew what a whopping catastrophe we faced. Away back in the years when I was a Frosh, and Tubby a Soph, and he condescended to spend part of the summer vac with me here in Shady Valley, the struggle had its beginning, for Dorothy could not see him then at all, and Tubby was for her from the first minute. Tubby could not see anything else. Dorothy completely obstructed his view of the landscape and rendered him helpless, so that -- to use a simile -- he was like a frog that has received its deathblow and merely lies on its back with its forepaws in the air and quivers. And that is just the thing that never did appeal to Dorothy Carter. The faithful Newfoundland thing never did draw loud cheers from her; her upbringing was such that she liked her sheiks up and coming and wide-awake.

I think, perhaps, Dorothy had seen too much of me for her own good. I mean that we were such neighbors that she couldn't help seeing that I am a marvel of a manager, always knowing what to do next -- and doing it -- and that spoiled her for a faithful but confusable soul like Tubby. She had seen too much efficiency. Probably, if I had turned over my hand, she would never have looked twice at Tubby or anyone else, but marriage was out of the question between us on account of our ages, she being a year older than I and a Soph at Wellesmith, which put any thought of an alliance out of the question. No man can be happy with a wife who starts in by treating him like a kid, saying, "Oh, yes, Billy; that's all very well, but wait until you're a Soph and have to tackle what I'm up against, and you won't think English Lit is such pie." At any rate, the moment Tubby saw Dorothy first was like the moment when a fellow whiffs his light roadster around a well-known corner at forty an hour and sees loom up in the middle of the road a few brief yards ahead of him a large stone church someone is moving. The first moment Tubby went cold as ice; then he went all to pieces.

Right then I had to take hold and begin to manage for him. You might almost say that this wedding that was resulting was my personally conducted romance for, as I have hinted, Tubby was struck brainless and Dorothy could not see the sterling core of him because whenever he neared her it turned to jelly and vibrated helplessly. It was up to me to peel the dead tissue from him and let her see the staunch and true Tubby that dwelt inside, and also to shoot a little starch into him so there might be something staunch for her to see.

I did it, too. Bit by bit I brought her to a realization that the pathetic-eyed hound that dogs her footsteps and is willing and eager to die for her is a better man than any of its Gunga Din fleas, no matter how snappy and up-and-doing they may be, and when Tubby came down in June for a brief breather after the curse of final exams and grad, she said him yea, and the date was fixed for October, when the leaves would be red, because she had always wanted an autumn foliage wedding.

Not so good, as far as I was concerned. It meant that I would have to use up most of my semester cuts to be on hand, but a man will do almost anything for a man he cherishes, and I knew Tubby could never get married successfully unless I was there to manage for him. Particularly when he is as big as Tubby and Dorothy is the sort of girl who wants her wedding to be the spiffiest ever. Just to think of anyone as big as Tubby butting into a classy wedding such as Dorothy would want, was enough to give any ordinary man the shivers, for Dorothy would go the limit for daintiness. She thinks normally in terms of spun-glass cobwebs, and Tubby, poor old soul, is apt to butt around like a horny-winged June bug, always bumping head on into things and falling flat on his back in the ink. But I was right up on my toes at the moment and looking for new worlds to manage, and the moment I received Tubby's wire I wired back "I'm on. Guarantee successful wedding or will forfeit the deposit."

I chased home in time to meet Tubby at the station. The weather was a bit against us, being hotter than midsummer with rain banked up all around the horizon, and the leaves had not turned red worth a cent. The minute I saw Tubby's big round lovable face I knew he was scared and that I was going to have my hands full. The first thing he said showed me I was guessing right.

"We ought to put this off, Bill," he said. "Honest, don't you think we ought to put it off?"

The poor man had been watching the trees all the way from Ohio, praying that it had been colder East and that the leaves had turned, but the Easter he got the greener they were, and he felt himself guilty.

"Never you mind that, old man," I said, whacking him on the back. "We don't have to doll up the chancel, so why worry? That's up to Dorothy, and the little girl has never failed herself yet; there'll be a frost tonight that will turn leaf crimson -- and if there isn't she'll have a gang out with peroxide or carbolic or something, before daylight tomorrow, turning every leaf in sight."

"That's it; that's just it, Bill," he said. "She's so wonderful, and I'm such a poor skate. I'll never be a credit to her. I'm such an inefficient mess. Bill, don't you think I ought to tell her she needn't go ahead with this if she don't want to?"

"Now, lissen, Tub," I said. "Just tie a can to that sort of talk right here. It don't mean anything. Dot is crazy about you; she's just miserable every minute she's not with you. All she wants is you. This is straight, Tub. I know."

"Do you think so, Bill? Do you think so?" he asked.

"Think so? I know so!" I told him, and that braced him up a little. Actually I wasn't just that sure of Dorothy. Tubby -- or his folks and this firm of Brace & Bradley -- has all the money in the world and then some, and I don't deny that there is always a possibility that even a nice girl is not too indifferent to money when it comes in million dollar rolls and the rolls are stacked more or less like cordwood. But that did not worry me; not if I could steer the affair past the wedding hour and set the two hearts adrift on life's sea, for I know old Tubby is one of Nature's Class A noblemen, and every hour she was with him would make Dorothy love him better and appreciate him more. He's a bit rough, like some of these other new-wealth fellows, but nothing rotten by any means, and I was willing to bet that if they were once married it would be, with Dot, a grand old discovery of eighteen-carat gold.

"All right, then, Bill," Tubby said, quite some cheered, "I'll leave it to you. If you say so it must be all right, but get me through the wedding, Bill. I'm depending on you for that, Bill. I'm going to be an awful mess if you don't steer me right and all the way through. You know what a mess I am, Bill."

"And that from you!" I said, pretending to be broken-hearted. "What's got you, Tubby? You haven't lost faith in me, have you? Haven't I managed old Yarvard -- practically with no help from the faculty or the Dean or the Prexy -- for four years? And you doubt me when it comes to a little thing like a wedding!"

So that was all right and cheerfulness reigned again, because what reason had I to doubt that the wedding would be pulled off all right? Up to the day and date when the invites were sent out I had not been so sure, not quite as much on Dorothy's account as on account of her mother, who comes close to ranking as a Tartar. She is, frankly, a Social Tartar Queen, and a real stickler. And that was what made me turn cold for an instant when old Tubby stood there in his room and gasped that he had parted from his pants in Cleveland and sent them to the ship. I could see Mrs. Carter in the front pew at one minute after half-past eight, looking calm as ice, but boiling inwardly because Tubby wasn't in view to the right of the altar; and I would see her at five minutes after eight when one of the ushers came rapidly up the aisle and whispered, "We're very sorry, Mrs. Carter, but Tubby's pants are absent and the wedding can't be held," but I could not see any wedding at all after that. That would be the end of it. Not in a thousand years would Tubby be forgiven, and when he died the ghost of Mrs. Carter would come and kick his headstone over, and stamp on it.

Downstairs I heard the ushers merrily taking a final glass of punch and I could see them, in my mind's eye, feeling for the thousandth time to see if the white gloves were in the pocket, a splendid band of Yarvard's best, some in rented dress suits and some in dress suits so tight that short breaths were in order. And there Tubby stood, scared to brittleness.

"Now wait!" I said. "Hold firm, old man! This is going to be all right. Don't worry a bit."

That was pure whistling in the graveyard stuff, and I admit it. It was pure instinct that made me throw out the words, just as any Yarvard man yells "We'll win! We'll win!" even when the score is 40 to 0 against us and the team being pushed back for a ten yeard loss every down. Because, no matter how you look at it, you can't take a groom to his wedding pantless, not even in a bathrobe. It isn't done.

The trouble was the size of dear old Tubby. He stacked up there, nobly huge, six feet six with a waist on him that would have done for one of these Terrible Turk wrestlers, and there wasn't a black pant in the house that would meet around his waist by eight inches. The first thought I had was, as in most cases, one of sorrow for myself, and a vow flashed through my mind, "Never again will I best-man an oversize!" but the old head got to work the next instant, just as it always does.

My first thought was of my father's pants, but Nature made the Dad an undersize and that was that.

"Never," my mind said, "best-man another wedding without an usher the same size and shape as the groom," but that was merely one of those wisecracks experience teaches us, and it did not help.

"Steady, old man; don't burst into tears," I urged Tubby. "The brain is working; I'll have it in a minute."

I thought of stays. A good stout pair of stays with the sturdy ushers singing a merry "Throw the man down!" chantey and pulling on the corset laces might contract Tubby enough to get into Bob Wilbur's trousers, and Bob could squeeze into mine, and I could take Dad's, and Dad wasn't needed at the wedding anyway. But there wasn't that much loose material to Tubby. He was solid muscle and bone, with nothing you could push up or pull down or squeeze inward. And time was flying, mind you.

"Boys! Hey, fellows!" I called, going to the stairs. "Up here, quick, all of you."

They came pouring up the stairs and into Tubby's room, falling all over each other and pushing and shoving, and when they saw old Tubby they gave a yell, and two of them began snapping his garters against his calves, uttering Hawaiian yuke notes gutterally.

"None of that, now!" I commanded. "Off him, fellows! This is a serious business. Tubby's pants are on the ship and we've got to be at the church in twenty-eight minutes."

"He can have mine," every one of them shouted.

"No, hold on! Keep your coats on!" I commanded, for several of them began to peel. "That's no good; he couldn't get into them. There's just one thing -- we've got to get pants."

"But its thirty-seven miles to New York, even if a shop was --"

"Can that, Bob!" I ordered. "No time for talk. I'm in command; we've got to work quick. Teamwork and rapid action. Are you with me? To the limit? To death and beyond?"

They let out a yell that told me their hearts were true to Yarvard, to Tubby, to pants and to me.

"Now, look here, fellows," I said, standing in front of them and slamming my fist into my cupped palm. I hate this, but it's the only way. We've got to hijack a pair of pants for Tubby. We've got only twenty-six minutes now, and we've got to get out and hold up a pair of pants. We've got to grab pants when and where found, and let the wedding guest beat his breast when he hears the loud bassoon. You get me? Are you with me?"

They took the idea with a little more levity than necessary.

"Get your vest and coat on Tubby," I ordered, and two of them started to help him. "Hat, too. Put a bathrobe on him, Skinny."

They started to put his blue tweed pants on him, too, but I stopped that mighty quick. We had no time to be putting on and taking off pants. I made a rush for my room and got some of my handkerchiefs and my shotgun, and led the way downstairs, crowding old Tubby amongst us in case Mom showed up, but she didn't.

I had pretty well figured by this time on what we would have to do, and when I had tied the handkerchief over my nose I sent the limousine rushing down to the road and half mile toward the church.

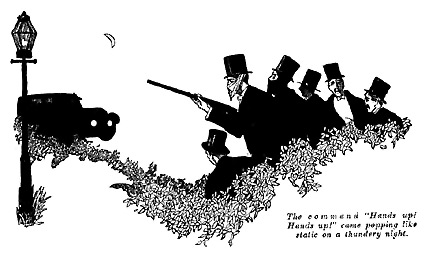

There I set it half across the road, and we piled out and lined up. Almost immediately a car drove in sight and I raised the shotgun and shouted. I might as well have shouted at the wind. The driver blew his horn and speeded up to forty-five miles and came at us like a streak of lightning -- and was by almost before we could jump out of his way.

"Confound the luck, fellows!" I cried. "There goes one of our chances -- that was Edward Peterman Overbury. We can't have that happen again."

I meant it, too, because Edward Peterman Overbury is one of the few big men in our neighborhood. I don't mean big financially, I mean in waistline. And it was no good holding up skinny lads or sawed-offs. When you need pants as badly as we needed pants for Tubby you need pants that will fit. It's no good getting a collection of off-size pants. A pile of pants as high as the church would not be a bit of use to us unless Tubby could wear a pair. Going to a man's own wedding with both arms festooned with pants does no good unless he has a pair on his legs, as common sense will tell you. And with all the hold-ups we are having these days the "safety first, run the man down and talk to him afterward" plan has become all too common.

But the old bean was still working, you may believe. In no time at all I had a lap rug on the ground and Tubby spread out on it, with Bob right there with an electric torch in his hand, and the rear end of the limousine backed into the ditch. Stage setting of a serious accident and wounded passenger, you understand, with wedding guests appealing to a good Samaritan for aid. I gave Sammy Hunter the shooting iron and went a bit up the road -- twenty yards or so -- because I was the only native in the bunch and knew the cars fairly well. There was no use holding up narrow-waisted men, or milk wagons, or goofs who came to the wedding in business suits.

It was a fair plan, if I do say so. If I kept silent my brave band of hijackers were to let the car pass. If I yelled "Help! Help!" the light was to be thrown on Tubby, who was to utter heart-breaking moans, and when the good Samaritan stopped his car the shotgun would poke into his face and in a moment we would have him unpanted, faced about, and his car beating it for home and pants, while we rapidly clothed Tubbys' lower extremities and rushed him to the altar. But you know what Burns said about plans, even the best of them. I let a dozen cars go by, only shouting "All right! We don't need help!" as they slowed down, because I knew the folks and recognized the gentlemen as underfed, anemic or merely skinny, but when the Undermore's big limousine came whiffing down the road I knew it was time for my gallant band to be busy.

I don't say I didn't have a qualm, and perhaps two or three qualms, when I recognized the car as the Undermore's, for Essie Undermore is one of my selects. I'll go as far as to say she is the selectest of my select, and you'll know what I mean by that when I say she's the only girl whose photograph ever reposed under my pillow as I slept. The others I may have stuck around my rooms, or carried next the faithful old heart for a month or two, but you know how that is. A man often falls but he don't always fall hard enough to break a rib. Too, too often a man discovers a fly in the amber and a worm in the rose, or the girl chucks him before he really falls hard enough to suffer permanent injury, but the cold truth is that Essie is the peach of all peaches, bar none.

What fussed me just a little was that there was a chance -- about ninety-nine chances out of a hundred, let's say -- that the propinquity thing might get in its work. Heart speak to heart, if you know what I mean. Because, to shoot the whole works, I more than half believed Essie was as strong for me as I was for her, and I can swear that you could blindfold me and nail me in a box with both ears stuffed with cotton and I would quiver with joy the instant Essie came within a mile of me. The good old soulmate stuff, if you get me. The heart recognizing its mate anywhere and any time, let the odds be what they may.

What I was afraid of was that Essie's heart might begin ringing like one of these alarm bells at a railway crossing as she neared me, and chitter out "It's Bill! It's dear old Bill!" For -- when you give it deep thought -- tying a handkerchief around one's face isn't deepest disguise possible, especially when he is in full dress and wearing white pearl shirt studs set with pinhead diamonds that Essie has admired more than once. And you can never tell about girls. They're queer. Fond as I hoped Essie's heart was toward me I had an intuition that she might get a little huffed if I held up her car and dragged her Dad forth and took his pants off him, even if we hastened him into Tubby's blue pair before the lapse of many moments.

The fact that the limousine was the Undermores' may have made me feel sickish, but it made me sure that now was our chance -- or never. The thought flashed through my mind that Ma Undermore and Essie were always the last to arrive at anything that even looked like a social event, and that it must now be close upon the time for Tubby to show up at the church -- if ever. I glimpsed a white shirt front in the limousine and sprang to the middle of the road, crying "Help! Help! Accident!" waving both my arms.

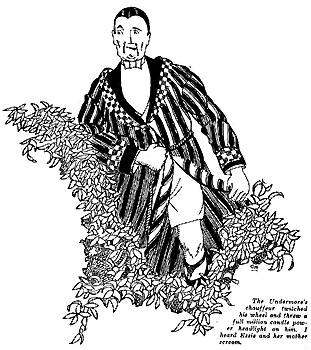

Instantly the light of the flash was thrown on Tubby and the limousine came to a stop, but the pocket torch's light was no longer necessary, for the Undermore's chauffeur twitched his wheel and threw a full million candle power headlight on him. Out into the middle of the road leaped Sammy Hunter, covering the whole landscape with the muzzle of the shotgun, and the command "Hands up! Hands up!" came popping like static on a thundery night. I heard Essie and her mother scream and had just time to rush back and grab the electric torch from Bob and aim it into the limousine, when the chauffeur shut off his headlights and started the car with a jerk that slung Essie's dear head back against the cushions of her seat in a way that might have broken her dear neck.

Sammy Hunter must have made a twelve-foot jump, because when the tail light of the limousine disappeared around the next curve he was still alive and unharmed.

"What now?" Bob asked. "I did think you were a whizz once, Bill, but you're a fizz when it comes to this hold-up business."

"Now, be calm -- be calm!" I said. "This is all going to be all right; there's nothing to worry about."

But I wasn't really anything like that sure. It was old Tubby that made me keep up the good old bluff, for he was near to collapse, the poor old scout! He sat there in the road on his rug, his pale legs extended in the dim light and his bathrobe hanging free over his well-clad upper portion, and the tears were beginning to ooze from his eyes.

"Bill," he said unsteadily, "I guess it's all up. I'm a dead one now, Bill. You did your best, and I'll never forget it, but I'm ruined. It's my own fault --"

"Cut that all out, Tub," I said. "It's going to be all right. Leave it to me. You know me. Did I ever fail you yet, Tubby?"

"But there are no pants!" poor old Tubby cried. "How can you get me pants when there are no pants?"

He stood up and bowed his head in bitter sorrow, and, the minute I saw him standing there like that, the big idea snapped into my head with a biff bingo!

"In the car! In the car, all of you!" I shouted.

They piled in, and dragged and pulled old Tubby in, and I grabbed the wheel and sent the old limousine humming toward the church. There was no room to park for blocks on either side of the church, and just ahead of us as we arrived, just pulling up at the church's awning, was the Carter's train of cars, with Dorothy and the delicious bridesmaids and flower girl and Dan Carter. I gave them a hearty cheer as we passed, and parked our car in the middle of the street at the side door of the church. Traffic regulations meant nothing in my young life just then.

Old Tubby was moaning piteously and trying to hide his legs under his bathrobe, and bracing himself for a struggle. I dare say he felt himself in one of those dreams a fellow has when just this sort of thing does seem to happen and he stands at the altar just about that unclothed. He wrote me afterward from Paris that for a few moments right there he misjudged me criminally. He wrote that for a few moments he feared that my well-known eagerness to put things over had got the best of me and that I did mean to pull the wedding through, whether or no, probably tying the lap rug around his waist and forcing him to go through with the wedding in a sort of Bonnie Highlander costume, full dress from the waist up and plaid steamer rug from the waist down. His agony at that moment was lest the steamer rug undo itself in the midst of the ceremony, and that was why he struggled when we tried to force him out of the limousine.

"Don't be a jackass!" I told him. "It's all right, Tubby. I've just remembered a pair of pants you can have," and that quieted him somewhat and I got him out and onto the church lawn. "Hop into it, now, fellows, I exclaimed. "Get together here -- we've only two minutes to work in."

I drew them into a circle, hands on shoulders, and talked fast.

"You get me?" I asked. "You get me? Who's got the blue pants? Bob handles the blue pants. Sam, you and I handle Tubby. The rest of you get the pants. pass them to me, and then help Bob. Signals! Down, Tubby!"

He went down on his back behind the big spirea bush beside the side door of the church. I took one look at him and was satisfied that he looked limp enough.

"Hide, you!" I said, and the rest of the hijackers hid behind the bush. Then I entered the church.

The organist was wandering over the keys searching for the well-known lost chord, soulfully, and I could glimpse through the crack of the door the filled church, and -- away back yonder -- Dorothy standing while a maid put a last pin in her dress and straightened out the long satin train. We had about half a minute to go. I turned to the left and opened the door of the robe room.

Reverend Wilson was standing there, his long silken robe falling in folds from his broad shoulders, but what I looked at was the two inches of pants below the robe. My heart jumped; they were black pants and no mistake.

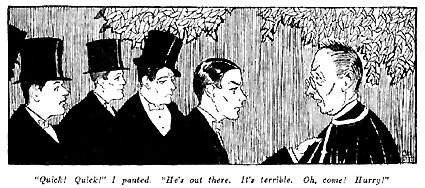

"I was just beginning to be nervous, William," he began, but I cut that short, you can bet! I put my hand on his arm and gasped as good a gasp as I could dig up.

"Quick! Quick!" I panted. "He's out there. It's terrible. Oh, come! Hurry!"

"My dear boy! My dear boy!" the reverend exclaimed. "What --"

"Don't waste time. It's Bradley -- flat on his back --"

That was enough for him. He pushed me and made for the door, and as he went I closed the door into the auditorium and the outside door. He turned to where Tubby lay.

"Jump him, fellows!" I shouted, and in an instant they were on him. "Now, Reverend," I said, as they held him, "this isn't going to be bad at all if we all just take it easy. Nobody is going to harm anybody. The trouble is that Tubby left his black pants in the trunk he sent to the steamer, and we want you to lend him yours. We'll de-pant you and put you in a perfectly good pair in no time at all. Get busy, fellows!"

I'll say for the Reverend that he was a good sport. We did not have to roughhouse him at all. Now and then he said, "Easy! A bit easy, my boys!" but he stood hopping on one leg and then hopping on the other while we peeled him, and -- really -- we were more bother than help when he came to hustling into the blue pants. We did not have to choke him into submission or any of the things I had been afraid of.

"Now, beat it, you fellows," I said, for it was time the ushers were at the front of the church to line up for the grand parade, enough harm having been done by their not having been there to seat the eager guests. But that did not bother me.

I've seen weddings before and I know that guests can find seats of their own, the ushers being mainly a draw-back and nuisance, running largely to white gloves and large feet.

As we walked to the fatal spot where we were to meet Dorothy, I gave old Tubby's legs the once over, and I was satisfied. Right on the dot of eight-thirty the organist began to pump out the "Here Comes" tune, and we were right there, as large as life. As Dorothy's gang began the hesitation drag up the aisle, dear old Tubby and I were on the spot marked X in the diagram, fully clothed and in our right minds. The old headpiece had triumphed again.

It wasn't until the affair was quite over and the reception at the Carters' had been undergone that the unknown hero of the hour, his eyes bright with triumph, got the jolts. The happy couple had departed and we had returned to the house.

"And now, Will, if you please," Mrs. Carter said to me in a hard voice, "will you tell me why the ushers were not on hand? It was utterly disgraceful; we had to ask some of the guests to ush. You were, I suppose, all drunk."

"And what on earth," Mr. Carter demanded, "did you do to Tubby? I never saw a man so nervous and scared and flabbergasted in my life. Wasn't that supposed to be your job -- to keep him calm?"

I laughed an insouciant laugh -- whatever that is. A man can suffer opprobrium, but a true man will never betray a friend. But this man Undermore had to butt in.

"What I want to know," he said, "is what your big idea was in trying to stage a hold-up when you were already due at the church. Of all the crazy pranks --"

And then it had to be Essie -- and I still claim she is the peachiest peach of the world's entire crop -- who gave me a cold and haughty stare.

"I should think so!" she exclaimed. "With poor Tubby Bradley laid out on a rug at the side of the road. Without his --"

"Essie!" said her mother sternly. "That will do!"

"It may do for you, mother," Essie said, giving me a withering glance, "but before Will expects me to count him among my acquaintances again he will have to do some explaining. There is something very, very strange about all this."

"Something decidedly strange," said Mrs. Carter, giving me a harsh look. "To me it seems as if he had intentionally tried to break up and prevent the wedding."

"If I think that," said old Carter, "I'll beat him within an inch of his life." He turned and glared at me.

And that was nice, wasn't it? I cleared my throat, trying to think what to say,

and I suppose I reddened a little. I cast back in memory to our dilemma of a little earlier in the evening. I saw my reputation gone and enemies created by the bushel and my future ruined and Essie lost to me forever, but if all that had to happen I couldn't help it. A man has to be true to his fellow man. and no matter what happened to me I wasn't going to tell that poor old Tubby had come to his wedding without pants. I tried to get the old head to dig up some snappy phrases that would fit the occasion, and I might have done it if Reverend Wilson had not joined the conference. He came up with his beaming benevolent smile and put his hand on my shoulder.

and I suppose I reddened a little. I cast back in memory to our dilemma of a little earlier in the evening. I saw my reputation gone and enemies created by the bushel and my future ruined and Essie lost to me forever, but if all that had to happen I couldn't help it. A man has to be true to his fellow man. and no matter what happened to me I wasn't going to tell that poor old Tubby had come to his wedding without pants. I tried to get the old head to dig up some snappy phrases that would fit the occasion, and I might have done it if Reverend Wilson had not joined the conference. He came up with his beaming benevolent smile and put his hand on my shoulder.

"Ah, William!" he said cheerfully. "Perhaps you can tell me whether your friend wore my trousers away with him or left them here?"

"My dear Mr. Wilson! Your trousers?" exclaimed Mrs. Carter.

So that was that. I can't say that Mrs. Carter laughed very heartily when the story was dragged from me, but Essie said "You're wonderful, Billy!" in a way that meant something or I'm no guesser, and old Carter, after I had told it all again over a cigar in his study, offered me the job in his concern. But I took the one Tubby offered me, instead.