from Woman's Home Companion

Mr. Jern's Ambition

by Ellis Parker Butler

In June Mr. Jern's daughter Rose was married to George Bonner and for two months before the wedding the most worrying matter for everyone was whether Mr. Jern would submit to wear pearl-gray spats and patent leather shoes for the church ceremony. Mrs. Jern thought he might wear patent-leather shoes but she did not believe he could ever be persuaded to wear spats; the attitude of Rose was, "I don't care! Father will just have to wear spats or I won't be married!" The great question was who was to ask Mr. Jern to wear spats. In the end George Bonner asked him.

"My best man and I and all the ushers are going to wear pearl-gray spats," George said to Mr. Jern: "patent leather shoes and pearl-gray spats. Do you want me to get yours when I am getting mine?"

"Why, yes, thank you, George," Mr. Jern said. "I wear six and a half B shoes," and that was all there was to it. In the end Mr. Jern was more concerned over the proper fit of his coat, the glossiness of his silk hat and the correctness of his tie and collar, than anyone connected with the wedding.

"You can never tell about your father," Mrs. Jern said in September, when talking it over with Rose.

An example of the surprises dormant in this most unsurprising man was the announcement Mr. Jern made on January first to his wife. He had had breakfast and Mrs. Jern had helped him into his overcoat -- she was half a head taller than Mr. Jern and considerably more robust -- and he walked to the door. He paused there as if he had forgotten something, felt in his pocket to see that he had a fresh handkerchief.

"By the way, Alma," he said, "I am going to retire this year."

It required a moment or two for Mrs. Jern fully to grasp this amazing statement so casually made.

"Oh, Joseph! I am so glad!" she exclaimed then. "And we can -- and can we have a little place in the country then?"

"That's possible," said Mr. Jern. "I don't see why not -- now."

Although Mrs. Jern was delighted, for owning a small place in the country was her heart's dearest desire, she did not press the matter then. She was too excited and astounded. Although she had wished Mr. Jern might retire -- he was sixty -- she had expected he never would. For one reason, she had no idea whether Mr. Jern was able to retire or not; and for another reason, she could hardly imagine Mr. Jern without his office to "go to." He was not a fussily busy man but he had "gone to" his office religiously every working day for thirty years. Mrs. Jern truthfully might have said that Mr. Jern lived for his office, if it had not been equally true that he lived for Mrs. Jern and their family.

Mr. Jern's vacations were never more than two weeks but Mrs. Jern and the family had gone to the country for July and August for many years. For the past ten years they had spent the two hot months at the same farm in the hills, a charming place on a lake where the children could have boating, swimming and fishing.

In March Mrs. Jern ventured to ask Mr. Jern a question.

"I ought to be writing the Dowseys, about July and August," she said. "Do you think we shall go there this year?"

Mr. Jern wore a small pointed beard which was gray. He pulled at it thoughtfully.

"You liked it there," he said.

"I was thinking of what you said about retiring this year," Mrs. Jern said and you can imagine her bending her head and biting off a thread to take away from the baldness of her words.

"Yes; that's so," Mr. Jern said and added, "It is only March. We'll have to think it over. We might buy a small place in that neighborhood, we like it so well up there."

Mr. Jern was a small man and he had never been very showy. He was not fussy about his food or his clothes or about anything else. He did not mind being contradicted and he had never been known to lose his temper. He was usually silent and this gave him the effect of being a thoughtful man but he did not actually think much. One thought often sufficed him for a full day; sometimes one thought was enough for several days. In the matter of thought he was a ruminating animal. On the other hand he had only one bad habit -- he liked to keep a small bit of tobacco tucked up under his upper lip, and to chew it a little when doing so would annoy nobody. Tobacco-chewing was a habit he had learned in the West when quite young.

In the West Mr. Jern had worked in a machine shop and there he had spent his free hours inventing a vending machine -- a penny-in-the-slot machine for selling newspapers. The machine contained a clock and a weighing scale and when the proper coin was dropped in the slot the machine handed out a newspaper on the margin of which was stamped the day, the hour, the exact minute and the buyer's exact weight in pounds and ounces.

The machine had no success in America but in Great Britain it presently found favor and Mr. Jern placed the patent with a concern in Liverpool which manufactured the machines and paid Mr. Jern a royalty. This royalty amounted to a satisfactory steady but not overwhelming income. For his business Mr. Jern needed only one room in an office building in New York with a desk large enough to endorse his Liverpool checks on, and on which to verify the Liverpool firm's monthly statements. In twenty-five years Mr. Jern had not found an error of sixpence in the statements.

In April Mr. Jern took his son Edgar, who was then twenty-four and a business college graduate, to the office and explained the business to him.

About the middle of May Mr. Jern surprised Mrs. Jern again.

"George knows how to drive a car," he said. "Why shouldn't you learn to drive a car, Alma?"

"Oh, Joseph," Mrs. Jern exclaimed, "I would love to!"

"Telephone to George," Mr. Jern said, "and if he can come over we will go down and look at a car."

The car they bought on George's recommendation was a small inexpensive sedan, and Mrs. Jern learned to drive in no time at all. She found George a delightful teacher. He not only knew how to drive but he knew how to teach with a laugh and a smile. The whole family loved George. They were confident that George was the best son-in-law and brother-in-law anyone ever had and he did bring to the Jerns a spirit of open merriment they had lacked. The whole family -- because Mr. Jern had been keyed low -- had keyed itself lower than need be, and George woke them up. He came into the apartment with a loud cheery "Hello, folks!" and he was almost the only person in the world who ever asked Mr. Jern how the vending machine was doing.

Mr. Jern thought he would probably retire in September. Edgar liked the country and might want to spend July and August there before taking over the office entirely, and Mr. Jern thought he would himself spend the first two weeks of August at the Dowsey farm. On the twenty-eighth of June, Sam getting out of high school at three o'clock, Mrs. Jern started for the farm at four, driving up with Millie and Sam.

Mrs. Jern was eager to be in the country. The Jerns' apartment was not far from Central Park and there are few places where more of our smaller wild birds can be found than in that oasis in the middle of the city, but, after all, Central Park is not country. For years Mrs. Jern had delighted in birds; she knew them by plumage and by song, and her greatest pleasure was to take her bird-glasses and explore a wood or lane or brook for birds. This is called "going birding" and to find a bird she had not already listed that year, when she had more than a hundred varieties on her list, was a real thrill for Mrs. Jern. That was her greatest reason for wanting a small place in the country. She longed to possess her own brook and woods and copses, and if she could have a bit of swamp where the red-wing blackbirds would cry warnings from the tops of waving cattails and long-billed marsh wrens would flutter up singing from the reeds, so much the better.

She did hope Mr. Jern would not in the end decide against a small place in the country. Mr. Jern had never seemed much interested in the country. He did not complain but he certainly did not get much excited over it. He did not care for swimming or boating or fishing, and birding left him quite cold.

"He isn't interested in birds at all," Mrs. Jern said to Rose the second week in July when Rose had gone up to the Dowsey farm.

"Neither is George, Mother," Rose said, "but George loves to get out into the country just the same. Father always seems placid enough in the country."

"Placid, yes! Your father is always placid, Rose, but I'm afraid the country bores him."

"I guess everything bores him a little," Rose said. "I think Father just isn't the enthusiastic sort. Did it ever strike you, Mother, that Father hasn't any ambition at all? Father is dear, but I mean he hasn't an ambition, like most men. There isn't anything he is interested in enough to want."

"I've tried to interest him in birds," said Mrs. Jern.

This was true, but Mr. Jern had not been interested in birds. When he came to the farm on his vacation Mr. Jern always went to his room and put on a pair of old shoes and an old thin coat and then found himself a stout cane of some sort. If Mrs. Jern said, "Joseph, would you like to go birding with me?" Mr. Jern invariably said, "Yes I would, Alma," but if she left it to him to choose the direction he selected the brook or a lane or the pebbly beach of the lake, never a copse or thicket or the woods. He did not mind the road but he never chose a grassy field.

If they were walking up the brook Mr. Jern would walk along the brook edge, his cane held clasped in his hands behind his back, his eyes down and his hat pulled over his eyes. On these excursions he allowed himself a somewhat larger bit of tobacco and he chewed it a little more vigorously, turning his head now and then to expectorate, and Mrs. Jern felt that he liked to take the walks for that reason perhaps, but if she stopped and called his attention to a glowing bank of clouds or to a view seen in the vista of a wood road, or to a hawk circling high, he would look up and say, "Yes," and instantly glance down again, mutely masticating.

At the farm, when Mrs. Jern did not claim him for a bird-walk Mr. Jern usually went for a solitary walk of his own. After breakfast or after lunch or after dinner he would stand around for a few minutes restlessly.

"Well," he would say, "I guess I'll go for a little walk."

He walked slowly, merely strolling, stopping to look at the ground or the pebbles. If Sam or Millie or, in earlier days, Rose or Edgar, wanted to go with him he was quite willing, almost glad, to have their company. As small children he often took them to gravel pits where they could play, digging small caves. He was content then to sit on a small boulder, or to move from one boulder to another, chewing gently at his tobacco, a mild and inoffensive little man, looking at the ground.

At ten o'clock at night on the last Saturday in July Mr. Jern was getting ready for bed when the telephone bell rang and he heard George Bonner's always cheerful voice.

"Hello, Pop!" George called. "I've got some great news for us. I'm going over into North Jersey and see if I can pick up a couple of trout. Want to come along?"

"Now, George, I don't care for fishing --" Mr. Jern began but George cut that short.

"All right, I'll be at your door at five A. M."

The brook George found was a fairly good babbling stream with pebbly bottom and banks and here and there a pool. George had two rods, but Mr. Jern would not let him rig up one for him.

"I don't care much for fishing, George," he repeated. "You go ahead and fish; I'll just walk along and sort of watch you. I'd rather."

So George let him have his way. Mr. Jern followed him up the stream, stopping when George stopped and going on when George went on, chewing a little larger piece of tobacco than when he was in town, and bending down now and then to pick up a pebble or a small stone.

At noon they went back to the car and sat on the grass to eat lunch. They talked of the three trout George had caught and it was not until the trout had been thoroughly discussed that Mr. Jern rather diffidently drew a small stone from his pocket, handing it to George.

"George," he asked, "what would you think of this, honestly?"

"It's flint," George said turning it over and over. "Yes, but I mean the shape of it, George," Mr. Jern said. "You wouldn't say it was anything, would you? That sort of nick there?"

"Piece of flint," George repeated. "You wouldn't say it was a piece of an arrowhead, one that had maybe got broken, would you?" Mr. Jern asked.

"No; that was never an arrowhead, Pop," George said. "I've picked up dozens of arrowheads -- well, maybe a dozen or so -- and that never was part of one."

"No," said Mr. Jern, "I didn't think it was," and he tossed the piece of flint into the near by brook. "You know, George," he said rather wistfully, "I never picked up an arrowhead in my life. No, sir; I never picked up a single arrowhead. I've walked -- why, I've walked a thousand miles, I'll warrant, and I've looked at a million, maybe a billion stones, and I've never picked up a single arrowhead."

"I guess they're getting scarce now, Pop."

"There was a boy I went with when I was a boy out west," Mr. Jern continued as if George had not spoken, "and we used to go around everywhere together. Swartz was his name -- Swatty Swartz -- and we went up a creek out there one day, just adventuring around, and all of a sudden he stooped down and picked up an arrowhead. A dandy one too. Well, sir, I guess I spent 'most all my time after that looking for arrowheads and I never found a one. I never have found a one. Now that's queer, ain't it?"

He was silent for a minute or two. "There must be some arrowheads lying around somewhere yet," he said. "They can't all have been picked up. George, have you picked up any lately?"

"I haven't looked for any, Pop," George told him.

That same Sunday afternoon Mrs. Jern and Mrs. Glenzer, who was another boarder who was fond of birds, drove to another lake to see what birds they could see. The car had let Mrs. Jern widen her birding greatly. They had started home along the lake when Mrs. Jern stopped her car suddenly.

"Louise!" she exclaimed. "Louise Glenzer, that is my house! If Joseph will buy me that house I'll never want another thing the whole rest of my life!"

"It don't seem to be for sale. There's no sign on it, Alma."

"I'm going to ask anyway," Mrs. Jern declared and she drove into the dooryard. It was several minutes after she had knocked on the door before anyone came, and then it was a very old woman.

"Is this place for sale?"

"Yes, we want to sell it," the old woman said. "My son says we had better sell and go and live with him."

"How much do you want for it? How many acres are there?"

"Sarah! Sarah!" came the voice of a man from an inner room, an old voice and tremulous. "Don't you say a word. Remember what Henry told us. If they want to buy, send them to Ed Rogers."

"Why, I know Ed Rogers," said Mrs. Jern. "At Midvale. I'll be glad to go to him. But could we just look through the house? And walk over the property?"

"Let 'em, Sarah," came the old man's voice and the old woman led the way through the house, showing the rooms, opening closet doors. It was Mrs. Jern's ideal country home, such a place as she had dreamed of. There was a sandy beach for bathing, the lake for rowing and fishing, a small swamp in a far corner, rolling pastures with ferns beside great boulders, copses and woodland where birds found sanctuary, and even a small brook with pools large enough for trout. The next day Mrs. Jern and Mrs. Glenzer went to see Ed Rogers.

"The Benner place? Yes, ma'am, I've got it for sale," Ed Rogers said. "Not even a sign on it yet; their son only listed it with me Saturday. And that's a place that will be snapped right up. If I was you, Mrs. Jern, I'd take that place this minute, if it's what you want."

Then Mrs. Jern had to explain Mr. Jern a little. She hoped he really meant to retire, she hoped he really meant to buy a place in the country; she would have to wait until she could talk with Mr. Jern. He was slow sometimes in making up his mind.

"I'll tell you what I'll do anyway," Ed Rogers said genially. "I'll sort of give you the first chance at it; I'll let you know if I have an inquiry."

The next week Mr. Jern went to the farm for his two weeks of vacation, George driving him up. Almost before Mr. Jern had gone to his room to change to his old shoes and coat Mrs. Jern had told George about the Benner place. The whole family had seen it, and they all loved it.

"I'll drive over with Rose tomorrow and see it," George said, but that evening when Mr. Jern had gone for his solitary walk and the family and Mrs. Glenzer sat on the porch, George leaned back against a post. He watched Mr. Jern going toward the brook and saw him stop to poke with his stick where a rivulet at the side of the road had unearthed a few pebbles.

"Do you know what he is looking for there?" George asked. "Arrowheads; Indian arrowheads. That's what he is always looking for when he walks along like that with his head down. He's a great old boy, Pop Jern is, but he's no arrowhead finder. He told me last Sunday he had been hunting for arrowheads ever since he was a boy, and he has never found a single one. Sixty -- fifty years!

Half a century! And he has never found one!"

Mrs. Jern leaned forward quickly in her chair.

"But -- but --" she exclaimed and then sat back again. Her heart was suddenly filled with an ache for Mr. Jern. She resaw him as, through all their years together and their hundreds of walks together and his innumerable walks alone, he trudged uncomplainingly with his eyes on the ground, seeking and seeking.

"But," said Mrs. Glenzer, "they haven't found --"

She too stopped short. She had been about to say that no arrowheads had been found there in years but the thought crossed her mind that if she said that, and Mr. Jern heard it repeated, he would never buy the Benner place for Mrs. Jern and she would lose her bird-loving friend of whom she had become so fond.

"I think I'll walk down to the little store," she said instead, for there was a telephone at the little store, and when she reached the store she called Ed Rogers. She was very direct and explicit in her advice to the real estate man.

"In the brook especially," she said.

Mr. Jern is sure to go to the brook almost immediately, and if you put one or two arrowheads where he will be pretty sure to find them --"

"There'll be arrowheads, and he'll find them," said Ed Rogers promptly.

When Mrs. Glenzer had hung up, Ed Rogers took a pencil and did some computing. His commission, if he sold the place to Mr. Jern, would be an even thousand dollars, and he would have Mr. Jern as a customer for insurance. If he could buy Indian arrowheads at twenty-five cents, he could get four hundred for one hundred dollars. It was worth a gamble.

Mrs. Jern meanwhile had gone into the house. She looked among the magazines on the table but did not find what she wanted, and she climbed the stairs to Sammy's room. His favorite magazine, The Outdoor Boy, lay on his bed and Mrs. Jern grasped it and turned the pages. She found what she wanted among the small advertisements: "20 diff. for'n coins .40; World's smallest coin .10; 3 arrowheads .10" -- and she hurried to her room and wrote a letter to the Elmore Curio Corporation in New York. She did not bother to compute but wrote a check for fifty dollars and asked that the arrowheads be sent by special delivery immediately. When she returned to the porch she bore the expression of an angel who has just relieved a sufferer's pain.

Ed Rogers used the telephone, calling up his friend Will Clemmings in New York.

"You'll know where to get some, Bill," he said. "Indian arrowheads -- some curio place. Blow in one hundred dollars for me and send them by express. They oughtn't to cost over a quarter of a dollar apiece." The best Will Clemmings could do, buying in quantity, it turned out, was six cents apiece but because it was such a large order the Star Curio Company threw in one hundred and eighty-four damaged arrowheads, lacking points or otherwise deficient.

Mrs. Jern no sooner settled herself in her chair than Millie beckoned to Sammy.

"Let's go around and sit in the hammock, Sam," she said.

When she was out of hearing she grasped Sam's arm impulsively. "Sam," she said, "did you hear what George said about Father all his life wanting to find arrowheads? Isn't it a shame? Don't you feel -- well, sort of sad about it, Sam?"

"Well, I can't help it, can I?" Sam asked.

"But that's it -- we can help it, Sam. We can buy some arrowheads, can't we? You know -- drop them where Father could find them."

"We could put them somewhere on that Benner place," Sam said, "and Father could find them when he went over to look at it."

"Mother," Edgar was saying about the same time, "if you aren't going to use the car right away I think I'll run over to Midvale; I need a couple of shirts pretty badly," and as Mrs. Jern did not want the car Edgar did drive over to Midvale. The telegram he sent was to his friend Cullen Williamson and was to this affect:

"Be a sport and buy about fifty dollars' worth of flint Indian arrowheads for me somewhere and send express in plain package tomorrow sure."

Then he bought two shirts he did not need and drove home with a quart of strawberry ice cream and the pleased expression of a man who has remembered his wife's birthday. George and Rose were just going upstairs but they remained down to share the ice cream.

"I want to show you something, Honey," George said when they were finally alone in their room and he boosted his suitcase onto the bed and opened it.

"George! Arrowheads!" she exclaimed. "Arrowheads! You are the dearest, most thoughtful man!"

"Two thousand arrowheads, no less!" he laughed happily. "That'll give the old boy a thrill or two, hey?"

It was no trouble at all to keep Mr. Jern from going to see the Benner place too soon. This gave young Sam and Millie a chance to pretend an all-day hike and carry their one hundred and eighty arrowheads a few days later to the Benner place and plant them as wisely as they knew how.

They had started home when Mrs. Jern drove up in her car and she did not see them nor they her as she placed her seven hundred and fifty arrowheads here and there -- mostly in the brook or along it.

Edgar, arriving about the middle of the afternoon, had seven hundred arrowheads, and toward evening George Bonner and Ed Rogers arrived simultaneously. Ed introduced himself and George explained that he was the son-in-law of Joseph Jern.

"Do you want him to buy this place?" Ed Rogers asked. "If you do I'll tell you something. You see this grip of mine? Do you know your father-in-law has been trying to pick up an Indian arrowhead ever since he was a boy? Well, sir, I've got eighteen hundred arrowheads right here in this grip, and I'm going to plant this place so thick with arrowheads that --"

"You see this suitcase?" George interrupted him. "I've got two thousand arrowheads in this suitcase!"

They planned the planting together, as was necessary unless they wished the Benner place to be paved with arrowheads. It was not an easy job, and when they had got down to the last hundred arrowheads Ed Rogers took the lot and threw them into the vegetable garden with an "Oh, thunder! Let's get through!"

The next day everyone brought pressure to bear upon Mr. Jern to induce him to go see the Benner place.

"Well, maybe I might," Mr. Jern said. "Maybe this afternoon. I don't know, though, about buying a place. Some things I don't just like about it up here. If you're not going birding, Alma, I don't know but I'll go for a little walk."

He wandered down the road toward the hillside where the road-menders had been excavating a few loads of gravel, and that was the last they saw of him until lunch.

"I guess it will be all right to go over and look at that place this afternoon, Alma," he said as he paused at the porch steps and took off his hat. "I don't know that it means much, my going, though. If you like it you'd better buy it, I guess. I'll be satisfied if you think it is all right."

He paused then to look off at the far fields and valleys and the lake.

"I like this country up here," he said to no one in particular. He put his hand in his pocket and drew something out. He held it toward George. "I found an arrowhead up there where they're digging gravel, George," Mr. Jern said.

"Joseph! You did?" cried Mrs. Jern. "Why, that's wonderful!"

"Nothing much to get excited about, I guess," Mr. Jern said with seeming indifference. "They find them most everywhere, I guess."

George glanced at Rose. A faint smile passed between them.

"When you find one of a thing you generally find a lot," George said. "That's the way it goes."

"I guess that's right," Mr. Jern agreed.

Ed Rogers drove up almost immediately after lunch and Mr. Jern made no objection whatever to going to see the Benner place. He stood on the porch while the others got ready and he kept his hand in his pocket. A bird lighted on a tree near by and Mr. Jern turned to Rose and asked her what bird it was. He had never asked about a bird before. He talked a great deal. He asked Ed Rogers about people and farms. He even interrupted Mrs. Glenzer to ask her what kind of snipe had yellow legs. All the way to the Benner place he talked but he kept his hand in his pocket, fingering the arrowhead he had found. Once or twice he took the arrowhead from his pocket, looked at it and put it back.

"Looks fine," Mr. Jern agreed. "House all right inside, Alma? Looks kept up in good shape. I guess we'll buy it, Alma."

"But you want to go through the house, Joseph," Mrs. Jern said. "You want to walk over the property and see the brook and the garden and the fields."

"You want to see the brook anyway," Ed Rogers said. "It certainly is a beautiful little brook."

"It's a dandy brook, Pop," George seconded. "Stony and pebbly and clear. I'll bet you could find arrowheads in that brook; nobody on the place for years but those two old people. What do you think, Rogers?"

"If you can't find arrowheads in that brook, Mr. Jern," Ed Rogers declared, "I won't ask you to buy this place, that's what I think."

"I'll bet -- I'll bet it is just full of them, Father," Sammy said eagerly.

We might walk up it a way and see if you do find any arrowheads, Joseph," Mrs. Jern said.

"Do you want to look for birds, Alma?" Mr. Jern asked.

"No; not today."

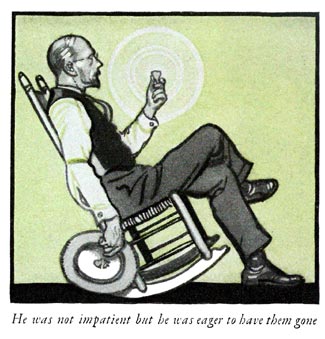

"Then I guess I'll just sit here while you folks look around," Mr.

Jern said. "I'll buy the place if you want it; it looks fine to me. Go along and I'll wait here."

He was not impatient because he was never impatient; but he was eager to have them gone so he could take out his arrowhead and look at it and study it and enjoy it. As nearly as he could remember it was a better arrowhead than Swatty Swartz had found.

"But, Pop," George Bonner exclaimed, thinking of the innumerable arrowheads he and Ed Rogers had scattered, "aren't you interested in finding arrowheads?"

"No, George, I guess not," said Mr. Jern in his gentle kindly voice. "I found one, George."

For, after all, ambition has two ends and a middle.