from Ladies' World

A Cross-stitch Penance

by Ellis Parker Butler

And so they lived happily ever after. That is the end of this story, or the end as far as it has gone, and it is over six months since the awful moments, so it is safe to say that that is the proper and logical finale. But it was a terrible half hour -- thirty minutes of boiled down, distilled, agonized bitterness.

And the thing next to the end, that shows what sort of a person Rita really is and how she took her lesson like a little lady, is a mere incident. Dawkins came over, looking as much as ever like a caricature, with his calabash pipe hanging from one corner of his mouth and his red hair mussed seven-ways-for-Sunday and his red slippers flapping at the heels, and dropped himself into one of our porch chairs.

"Hot!" he said. "Thought you might have a breeze over here, so I came over.

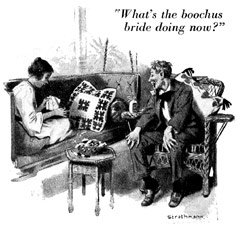

What's the boochus bride doing now?"

What's the boochus bride doing now?"

"Penance," said Rita softly. "I'm doing a cross-stitch frame for my own husband's photograph. It is to hang in my bedroom, where I can always, always, always see it."

Dawkins always called her the "boochus bride" because it made her go for him. The first time he slip-slopped over in his red slippers after we had moved to Westcote, Rita showed him the photograph of herself in her bridal togs -- veil and flowers and train and all. Mrs. Dawkins seemed properly impressed, but Dawkins just faked an awful admiration.

"Um!" he said, "that is a boochus bride!"

Rita struck him with the photograph immediately.

"You horrid thing!" she said. "I feel like pulling your hair."

"Pull it if you must, but don't muss if you pull," said Dawkins, whose hair always looks like a field of red grass in a storm. Dawkins seemed to like to come over, and he liked to tease Rita. Mrs. Dawkins was born older than Rita, or acquired oldness trying to manage Dawkins, who is almost a genius and who writes, and she has a reserved, elderly air, although she can't be over twenty-eight.

As I said, it seemed to amuse Dawkins to come over and tease Rita. She said he was horrid, but she liked him, and I liked him, and we all liked each other, and after we forgot he had a streak of genius in him and got used to his hair and red slippers, we made a nice, cozy pair of friendly suburban couples. That was as it should be, for we were four of different kinds: Crazy Dawkins, sedate Mrs. Dawkins, little spitfire Rita and common business man I.

I would take back the "spitfire" as applied to Rita, if I could think of a better word. I mean it as it is applied to kittens -- cunning, cuddling, cozy little creatures ready for a mock quarrel or a boisterous play, tremendously affectionate and -- to change from kittens to Rita -- brown-eyed, sympathetic, laughing and merry.

And there she sat curled up in the couch hammock, with her needle busy, answering Dawkins and saying in the meekest little voice:

"Penance! I'm doing a cross-stitch frame for my own husband's photograph. It is to hang in my bedroom, where I can always, always, always see it." So I changed the subject.

"Dawk," I said, "will you have a cigar?"

"Same kind you had last time I was over?"

"Same."

"Ex-cuse me!" said Dawkins. "I prefer my own stewed hay."

So then -- although it had nothing to do with Dawk or his tobacco -- I slipped over and pretended to see how Rita was getting along with her embroidery, but I let my hand touch her cheek softly, and she looked up happily, because she knew I had forgiven her. And then, as I said before, we all lived happily ever after.

Writing the end of a story, they tell me, is always the hardest part, and now, having the end in good shape, I will write the beginning, which begins much the same way, except that Dawk did not come over in his red slippers. He came over in shoes, but his hair was as mussy as ever.

"'Lo, folks!" he said. "I didn't pay my grocer this week."

"Well, what has that got to do with the war in Mexico?" I asked, this being my best at a joke, for Rita called his hair the "insurgent army."

"Why," said Dawk, "it means I have forty cents left and they're giving my two-reel romance at the Upper Westcote movie place, and the Missus sent me over to get you and take you there, so you wouldn't miss the treat of your lives. Come along and see the real thriller of the twentieth century."

Well, of course, we went. Dawk had told us, and Mrs. Dawk had told us, about Dawk's two-reel film. Dawk called it "my fillum drammer," and Mrs. Dawk spoke of it respectfully as being, perhaps, a wedge by which Dawk might pry open a new source of income. Dawk always ragged it frightfully.

"At this point," he used to say, "the villyum grabs the herowine by the slack of her neck and everybody weeps." Or "so the old goozer kerwallops the boochus gurrul and the tears in the balcony slosh down and drown the guy what punishes the planner."

He could keep us laughing by the hour while he described the plot and action of his two reel "fillum drammer," but Mrs. Dawkins rather disliked the way he spoke of it.

"He pretends it is a penny dreadful thing," she would say, "but it is really very touching. I wept both times I saw it." We set out for the movie show in gay spirits, stopping for Mrs. Dawkins. She had rigged herself up some. I think she had some vague idea that there might be calls for the author, and that in that case she should be dressed to do Dawk credit. Rita was in white -- no matter what -- and I was just business-suited as usual. No one seemed to know that Dawk had written the film play -- his name was not advertised -- and we stood in line like the rest and rushed for the best seats, and got good ones, halfway down.

We had a reel of wild western life first, and another of romance in the African veld, and a reel of somebody's weekly, with the Czar and a good assortment of kings and floods and fire ruins, and then the screen announced the next feature as "Dorothy's Love Match," and Dawk gave us all fair warning.

"If ye have blubs, prepare to blubber now!" he said, and the reel started.

Dawk sat in the aisle seat, with me next, then Rita, then Mrs. Dawkins, and all through the two reels Dawk gave me asides about the pictures: "Fat but fair"; and "Now he's going to make her swallow her gum -- now! now! now. There, I told you!" "Now she's going to mourn the loss of her tutti-frutti. Told you she would!" If anyone could have spoiled it for me, Dawk would have, but even his ragging couldn't quite do that. Every woman in the place was sobbing before the first reel was half finished, and the thing went into the second reel with the whole theatre in a breathless suspense. The men in the theatre, of course, did not weep, but I felt rather queer, and I admit it. I doubt if Mrs. Dawk wept, but she had seen the film twice before. That takes the edge off the most pathetic things.

It was a wonderful drama and doubly big because it was so simple in its idea -- a young bride, the young husband who fell in love with another woman, the jealousy of the bride and the following cruelty of the husband. When we came out of the theatre, Rita clung convulsively to my arm. It was not until we were almost home that she laughed, a little hysterically, at Dawk's nonsense. We went into Dawk's to have a cool drink, and on the way home Rita clung to my arm as before. "You'll never, never love anyone else, will you?" she pleaded. "And if you do, you'll tell me right away, won't you?"

"Don't be a goose," I said.

"But promise!" she insisted. "You won't leave me to find it out, and suffer, will you?"

"Oh, tut! Don't be a silly!" I said. A man hates to talk about such things as if they were serious.

"But promise," she said again.

"Oh, sure! I promise." I laughed.

It was such nonsense I couldn't take it seriously, and by the time we were home -- which wasn't far -- she was herself again. We sat on the porch awhile and talked about Dawk's "fillum drammer" and then we went upstairs. I imagine Rita did not sleep well. She was rather quiet when she awakened in the morning, and several times while she was dressing, she sat and stared at me, as if she was still dreaming, but she was dressed before I was and was giving her hair a last touch in the mirror as I put on my coat. I could see her face in the mirror, and, of course, she could see my reflection there, and suddenly I saw her draw herself up. She glared at my reflection in the mirror a moment and then she turned sharply and came toward me.

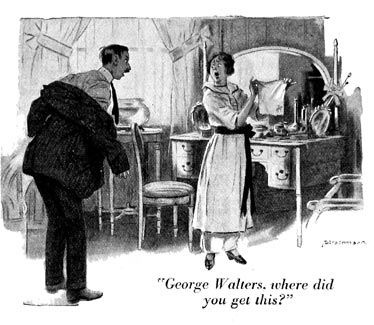

"What's the matter?" I asked.

"Stop! Stay where you are!" she commanded,

and she came to me and put out her hand and took something from my coat pocket -- the side pocket on the right side of my coat. She turned her back to me and tried to hide what she had taken, but Rita is small and I saw the edge of what seemed to be a handkerchief. She turned on me like a flash.

and she came to me and put out her hand and took something from my coat pocket -- the side pocket on the right side of my coat. She turned her back to me and tried to hide what she had taken, but Rita is small and I saw the edge of what seemed to be a handkerchief. She turned on me like a flash.

"George Walters, where did you get this?" she demanded, her eyes one brown flame, and she held the handkerchief spread out before my eyes.

Well, I didn't know where I had got it. I had never seen the thing before. I saw it was a handkerchief, and I saw it had a narrow pink border, and something that looked like pink roses embroidered in one corner, but I would have sworn I had never seen it before. I held out my hand and stepped forward to take it.

"Let me see it," I said, but she stepped back and jerked her hand behind her and glared -- simply glared at me. No other word describes the look she gave me.

"Don't you dare!" she cried, and I'll let that adjective "spitfire" stand after all. She was breathing deep, and her left hand opened and closed convulsively. "Where did you get this handkerchief?" she demanded again, and her words were like bits of hard metal, clipped off.

"Now, Rita," I said, "don't act that way. I don't know where it came from. Let me see it."

"I know where you got it!" she blazed. "Some woman gave it to you. Look at it!" she cried, shaking it in my face. "Who'd carry that kind of handkerchief? Some blonde! Who gave you that handkerchief?"

I had seen Rita in various moods and I had loved her in all of them, but this was a mood in which I had never seen her, and I did not even like it. The child was crazy with jealousy, absolutely crazy with it.

"Let me see it!" I ordered. "Don't I tell you I know nothing about the thing? How can I tell you anything about a thing I have never so much as seen? Rita! Let -- me see it."

"Let you see it!" she cried scornfully. "Oh, yes! you need to see it! You are so innocent!"

She became dangerously calm.

"George," she said, "will you tell me where you got this handkerchief? I am not unreasonable. I can forgive if you are fair and frank with me. You promised, only last night, to tell me if any other woman took your love away from me. Will you tell me now?"

What do you think of that? All I need do was to tell her the name of the woman who owned the handkerchief, and she wouldn't let me see the handkerchief! And I had never seen the handkerchief before. But it was no laughing matter with Rita. I could see that. It meant that the heaven that had been our life together up to that moment had crumbled, had dissolved from beneath her feet. In a moment I was lost to her, and all her future happiness was lost. She was so white, as she stood there, and so heart-wrenched and so pitiful!

"Rita, dear," I said quite calmly, "will you please listen to me? Let me see the handkerchief and perhaps I can remember something about it. I give you my word I know nothing about it. I can't tell you what I don't know, can I? Just let me see it."

The next few minutes were terrible. I lost my temper. Not at first, but before she finished. She was like a fury. If I offered to come near her, she threatened to spring on me and scratch my eyes out; she screamed that I must tell her who the woman was, and every calming word seemed to increase her rage. I begged and pleaded with her, but she was quite irrational -- she would not listen. Then I lost my temper, too. I told her she was being a little fool; that I would not stay and listen to such nonsense. I told her that when she had come to her senses, she could come to me, and if I knew anything about the handkerchief I would tell her, but I wouldn't be made a fool of in any such way. Then I went out of the room in a rage and dashed into the bathroom, because it was the nearest haven, and slammed the door.

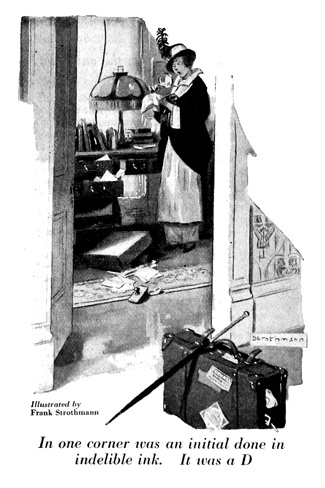

But even then I was not angry with Rita -- only with the senseless mood she had fallen into. Jealousy, I knew, was a sort of horrid nightmare, with which one struggled almost in vain, and I was sorry for Rita. Sorry, but offended, too -- and I thought justly -- that she should pick the first scrap of a chance to accuse me of paltry fooling with some other woman. I sat on the edge of the bathtub and gritted my teeth, waiting for Rita to come to her senses and tap at the door. Then I heard her descending the stairs. She went down slowly, a step at a time, as the saying is, as if to give me an opportunity to come out and make my confession. Then there was silence. I opened the door and looked down. Her suitcase, with stray ends of white protruding under the closed lid, stood in the lower hall. Rita was leaving me.

As I stood there, Rita came out of our little living room, hatted and ready for the street. Righteous anger showed in every line of her. From the top of a flight of stairs a person gets a peculiar view of anyone at the bottom. It is a sort of semi-bird's-eye view and, in a time of quarrel, a most unpleasant view. Face to face, on the same level, things may happen naturally. A couple of angry persons can continue the quarrel, or some sudden burst of feeling can throw one into the other's arms for a good tear-storm of reconciliation. But, looking down from the floor above, a person sees every stiffened attitude of anger in the one below and the distance is too great to permit the impulsive embrace. No one can reach impulsively down a whole flight of stairs. And when a man is angrily intrenched in a bath-room and his wife has her suit-case adjacent to a front door and shows by every twitch of her back that she is raving angry, he does not feel like sliding down the banister to clasp her in his arms.

Rita did not see me. She did not look up. She snapped open her purse and snapped it shut again, took a step toward the back hall, and turned away again -- she had an impulse to telephone for a cab, but decided not to -- and she picked up the suit-case and put it down again. She was not hesitating. She was thinking the many things a woman thinks when she is about to leave a man's house for the last time and forever. And, suddenly, she turned to the living room again and entered it.

I did not see what happened in the living room, but I know. Rita entered the room and angered -- there is no other word for it -- angered violently over to the reading table and jerked out one drawer after another. In the fourth drawer she found our reading glass and, standing there, she searched the handkerchief through the reading glass. I think she may have had some idea of going forth to tear some bleached blonde's hair before she went to her mother's,

if she found any evidence of ownership of the handkerchief. And she found it!

if she found any evidence of ownership of the handkerchief. And she found it!

In one corner, half hidden by the border and the tiny pink roses, was an initial done in indelible ink. It was a D.

Rita stood there, holding the handkerchief and tapping one foot angrily, thinking over all the Dollies and Dorothys and Daisys in town, or trying to think of one of them, and then -- suddenly -- she gasped twice and made a couple of panicky steps toward the door, and then stopped short and held the handkerchief clasped and crumpled in her two hands and just looked at the wall and was scared. Finally she opened the door very slowly and went into the hall, helping herself by placing one of her trembling hands against the doorframe, for she was as weak as a kitten. She actually forced herself to the telephone in the back hall, for she was physically unable to walk, she had such a fit of trembling. At the time, I was sitting on the edge of the bathtub, waiting to hear the front door slam. She took down the receiver and this is what she said, trying to make her voice sound indifferent and natural:

"Central, 780 Westcote, please.

"Hello! Is that you, Mrs. Dawkins? This is Rita.

"I -- did you -- didn't I borrow your handkerchief last night when I was weeping over Dawk's movie?

"Yes -- I must have put it in George's pocket. A pink border and pink roses?

"Yes -- no -- I -- it's all right -- I just wanted -- I just wondered -- I -- I -- Thank you! Thank you!"

If I were a "sob sister" -- one of the talented women who write columns for the daily papers on such subjects as "Is Jealousy Ever Justifiable?" "Is Love Destroyed by Baldness?" and so on, I would write a great article on "How Should a Repentant Wife Come Upstairs when She Has Discovered That The Handkerchief She Found In Her Husband's Pocket, And Which She Thought Evidence Of His Infidelity, Is -- After All -- Mrs. Dawkins's Handkerchief Which She Herself (The Perturbed Wife) Borrowed From Mrs. Dawkins At The Movie Show Last Night?"

I might use as a sub-head the words, "How Should She, If Her Husband, Still Justly Angry At What He Considers An Unjust Accusation, Is Sitting On The Edge Of The Bathtub, With The Door Closed?"

Some might say the proper way to ascend the stairs in such a case would be rapidly, with a cry of joy, but you must remember what it meant to Rita. It is horrid to have to ask forgiveness in any event, but to have to say, "George, I was wrong; the handkerchief is Mrs. Dawkins's; I put it in your pocket myself!" is especially hard immediately after such a storm of jealousy and anger as poor Rita had gone through.

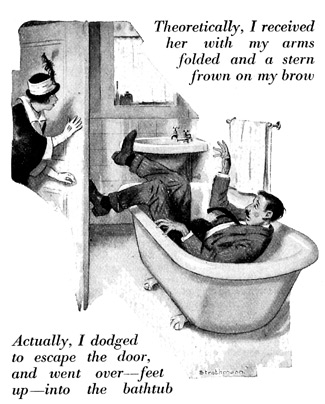

Rita turned from the telephone and fairly dragged herself to the foot of the stairs, and -- step by step -- she abased herself upward, growing meeker and meeker, and more and more contrite and pitiful and ashamed at each step. At the top of the stairs she stood a moment or two, with her hand on the bathroom doorknob, trying to screw up her courage. Then she made one big effort of it and threw open the door.

Theoretically, I received her with my arms folded and a stern frown on my brow. That was what I had planned. Actually, however, I dodged my head backward to escape the edge of the door, and went over -- feet up -- into the bathtub.

I think Rita thought for a moment that I had suicided into the tub and that she had arrived in time to witness my last throes, but the word I said, as my head struck the other rim of the bathtub, reassured her; and when she saw how the foot she had not grabbed was waving in the air, and how I was struggling to arise and could not because she was holding the other, she giggled. She giggled, and then she laughed hysterically, and cried hysterically. It was an entirely mussy and undramatic finale, with undignified gettings out of bathtubs instead of stern reproofs, and hysterical kissings instead of contrite pleas for forgiveness, but it served. As we went down to breakfast, she said one thing:

I think Rita thought for a moment that I had suicided into the tub and that she had arrived in time to witness my last throes, but the word I said, as my head struck the other rim of the bathtub, reassured her; and when she saw how the foot she had not grabbed was waving in the air, and how I was struggling to arise and could not because she was holding the other, she giggled. She giggled, and then she laughed hysterically, and cried hysterically. It was an entirely mussy and undramatic finale, with undignified gettings out of bathtubs instead of stern reproofs, and hysterical kissings instead of contrite pleas for forgiveness, but it served. As we went down to breakfast, she said one thing:

"Oh, George," she said, "I wish you would just whip me and whip me, so I should remember never, never to be jealous again."

"Forget it!" I said. "What do you think this is, a 'fillum drammer'?"

So that settled it so far as I was concerned, but when I came home that evening, Rita was embroidering. She had the pink-bordered, pink-rosed handkerchief, doing cross-stitch to it, but she would not say what she was doing. Until -- to get back to the next to the last of the story -- Dawkins came over, looking as much as ever like a caricature, with his calabash pipe hanging from one corner of his mouth and his red hair mussed seven-ways-for-Sunday, his red slippers flapping at the heels, and dropped himself into one of our porch chairs.

"Hot!" he said. "Thought you might have a breeze over here, so I came over. What's the boochus bride doing now?"

"Penance," said Rita softly. "I'm doing a cross-stitch frame for my own husband's photograph. It is to hang in my bedroom, where I can always, always, always see it."

Cross-stitching Mrs. Dawkins's handkerchief, to hang where it would be a constant penance, you understand. Do you get that point? That's the point I wish, as Dawk would say, "to get over." Because that shows just what kind of a little all-right this wife of mine is.

And so, as I ended the story when I began, they lived happily ever after! At least Rita and I have so far, and it is several days later now; and Dawk has, because Rita had to tell him about the handkerchief episode, and he says the new "fillum drammer" he is making of it will be a "reg'lar rip-snort weep-fetcher." And Mrs. Dawkins has, because she is always happy when Dawk is working at the genius job. Yes, we all lived happily ever after.