Millingham's Cat-Fooler

by Ellis Parker Butler

The way Millingham happened to mention hose to me in the first place was that I had been reading about snakes and I was telling him -- we were leaning on the fence that separates our gardens -- that the reason there are so few snakes left in places where people live was because of cats. Snakes hate cats, because cats kill them.

I told Millingham that there is nothing a cat hates worse than a snake and, as people always have cats when they go pioneering into new places, it is not long until the cats have chased the snakes away, or killed them.

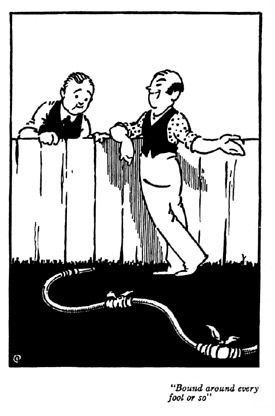

Millingham said yes, he had noticed that. He wiped his face with the back of his shirtsleeve -- it was a hot day to be working in a garden -- and asked me to look at the hose that lay on his lawn. So I looked at it.

"Well," said Millingham, "you know our cat."

I said yes, I knew his cat perfectly.

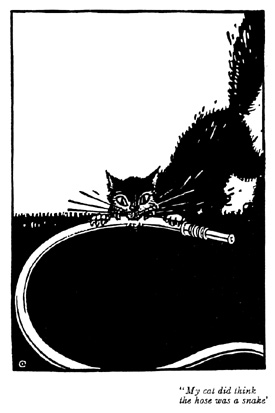

"Well," said Millingham, "one day when we first got that cat I got out that rubber hose and hitched it onto the faucet at the back of the house and stretched it out toward the garden, with the nozzle on the other end; that cat was sitting on the back steps as calm as you please. Just sitting there, you understand, happy and contented and thoughtless, licking her paws or maybe the fur on her wishbone. Anyway, she was just sitting there. Purring. I guess she was purring and licking. So I went to the faucet and turned on the water and the moment the nozzle began to hiss -- it was set to spray, you understand -- the moment it began to hiss, that cat made one jump from the top step and landed on that hose close to the nozzle --"

"Fifty feet?" I asked, but not unkindly.

"Well, maybe she made two jumps of it," said Millingham, "but she landed on the hose with every claw out and her teeth bare and growling -- you know how a cat growls when it is mad."

"I thought they yowled," I said.

"Yes. That's the word," said Millingham. "She yowled, and spat, and leaped and tried to bite the nozzle just back of the neck, and kill it. She thought it was a snake. You see, Brownson, it looked like a snake; to a cat a rubber hose looks like a snake --"

"Millingham," I said, "I have always admired you and believed you and considered you an honest, reliable neighbor, but --"

"But what?" he asked anxiously.

I shook my head and pointed to his hose. Then a thought came to me.

"I see!" I said. "The cat has bad eyes. It could not see very well. Of course, if a cat had cataracts, or pink eye, or something, it might think that hose of yours was a snake. I understand now. The cat was blind -- nearly blind."

Millingham blushed. He was tanned a good deal, from working in the garden, but he blushed.

"Otherwise, Millingham," I said severely, "I cannot believe that any cat, even a crazy cat, could think for one moment that that hose was a snake."

Why, not even an Irish kitten that had never been away from the Emerald Isle (where there are no snakes) and who only knew of snakes by hearsay, or by reading some snake dealer's catalogue, would have believed Millingham's hose was a snake. It looked more like a caterpillar -- a fifty-foot, water-haired caterpillar that had peeled off and blistered up and was squirting out water-hairs all along its length. Snake! A nice looking snake! Who ever saw a snake bound around every foot or so with old socks, pieces of kimono, and back breadths of the skirt Mr. Millingham's mother-in-law wore when she went to Boston to visit her husband's sister? Millingham's hose did not look like a snake, it looked like a boiled eel that was trying to be a fifty-foot national geyser park.

"No, Millingham," I said, "this time you have gone too far. You have lied to me. No cat would think that hose was a snake."

Millingham looked distressed.

"It -- it was a new hose then," he said.

I said nothing. I detest people who qualify their stories with excuses and explanations.

"Very well, Brownson," Millingham said stiffly. "You need not believe me, but I will show you. I cannot have my word doubted. I will get a new hose and then I will show you that my word is not to be questioned."

"Word or no word, doubt or no doubt," I said stiffly, "it is time you bought a new hose. That hose of yours is a disgrace to the neighborhood."

"You ought to know," said Millingham in an extremely unpleasant tone, "you use it more than I do."

This was exceedingly unkind of Millingham and I told him so. It is not my fault if his hose is in my yard most of the time. I borrow it only when I need it, and I carry it from his yard into mine, and if he does not want it in my yard he has a perfect right to carry it back whenever he chooses. I never hide it from him. I leave it in plain sight, wherever I used it last. I do not, as Millingham does, try to hide it, and I told him so.

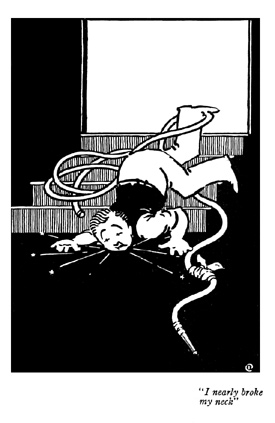

"And as for that, Millingham," I said with dignity, "I am through with using your hose. Only yesterday evening I went to get it, supposing you had hung it properly over three pegs in your cellar -- as I had a right to suppose -- and, when I ran lightly down your cellar steps, the hose was there and I stepped on it and nearly broke my neck. I do not call a neighbor who leaves his hose in ambush on his dark cellar stairs a good neighbor; I call him an incipient murderer."

"Good!" said Millingham, but in a bitter tone. "Good! Now, perhaps, I may be able to use my own hose on my own lawn and garden once or twice a season, for one thing is sure, Brownson; never again shall you use my hose. When a man, no matter how good a neighbor he may be otherwise, calls me a prevaricator and an incipient murderer, I refuse to lend him my hose, even if it does look like a boiled eel."

He said the last word sarcastically and I knew then his feelings were hurt. Millingham is touchy. His temper is easily ruffled. That, and the kind of hose he harbors, are the things I like least about him.

The next afternoon I left my office a little earlier than usual and hurried to Westcote -- which is our town --

and to the local hardware store, because I meant to show Millingham that I did not care a hang whether he was angry or not -- that I could easily afford to support a hose of my own.

I meant, when Millingham reached home, to have him see me in my garden indolently spraying my radishes and lettuce and pole beans with a handsome new hose with a brand-new glittering nozzle in my hand. Then, if he asked to borrow it, I would say carelessly, "No, Millingham, good neighbors neither borrow nor lend." That would crush him. I would then add, nonchalantly, "By the way, I thought you were going to buy a new hose. I don't see it," and that would practically drive him into the ground, because Millingham is one of those men who put off doing things.

I meant, when Millingham reached home, to have him see me in my garden indolently spraying my radishes and lettuce and pole beans with a handsome new hose with a brand-new glittering nozzle in my hand. Then, if he asked to borrow it, I would say carelessly, "No, Millingham, good neighbors neither borrow nor lend." That would crush him. I would then add, nonchalantly, "By the way, I thought you were going to buy a new hose. I don't see it," and that would practically drive him into the ground, because Millingham is one of those men who put off doing things.

Unfortunately, when I entered the hardware store, Millingham was already there. He was standing at the counter, tapping on it nervously with his fingers and glancing over his shoulder toward the door. When he saw me he colored and seemed to stiffen, but I walked right up to where he stood, because the hardware man was approaching him behind the counter.

"I want to buy some hose," I said in a firm strong voice, "show me some."

"Now, hold on!" said Millingham stubbornly in an unpleasant tone: "I was here first. I demand to be waited on first."

"What can I show you?" asked the hardware man politely.

"I want hose," said Millingham. "Garden hose."

"Then" said the hardware man, sighing deeply, "I can attend to you both at once. Step back here, please."

"I prefer," said Millingham, "to have the hose brought here. I have been standing here ten minutes and it is my turn to be waited on."

He cast a meaning glance my way to indicate that I was an annoying interloper. The hardware man -- his name is Kutz -- shook his head gloomily.

"You'll both have to come to the place where the hose is kept," said he. "We have a good many kinds of hose."

Millingham seemed surprised. I was surprised myself. Of course I don't know anything about hose except that it is hollow, but I always thought it was all pretty much alike. I concealed my feelings, however.

"Of course," I said, "anyone ought to know there are different kinds of hose. There's black hose and red hose and nearly white hose. This gentleman is no doubt ignorant of them, but I'm not. I will go with you to look at the hose."

"Don't think you're so all-fired smart, Brownson," said Millingham rudely. "I know more about hose than you do. Show us what you have, Mr. Kutz," and he walked toward the space at the rear of the store where the hose was kept. I followed him.

"Well, here's the hose," said Kutz, in the tone of a man with a hard job ahead of him. "What kind of hose did you say you wanted?"

Millingham stared around with a puzzled look. There were coils and coils of hose reaching to the wall on both sides. They didn't look very different from each other and neither of us seemed to have an answer ready.

"What kind of hose did you want?" repeated Mr. Kutz, as if hose were the bane of his existence. "Do you want half-inch hose or three-quarter-inch hose or inch hose? I got 'em all. Do you want 25-foot lengths or 50-foot lengths or hose cut off in lengths just to suit you?

I stood back and waited. That man Millingham makes me sick. There he was pretending to know all about hose and cats and snakes -- pretending to be a real hose expert -- and he stood like a ninny with his mouth open staring at the piles of hose.

"We're waiting, Millingham," I said sarcastically.

"There are different kinds of hose, too," said Mr. Kutz. "There is wrapped hose and you can get it in 5-ply and 6-ply and 7-ply, according to how much you want to pay for it. And there is molded hose, which isn't made in layers but is made quite differently. Did you think you wanted wrapped hose or molded hose? What with the kinds and qualities and the lengths and the sizes, I have got about 57 varieties of hose. I have got enough money tied up in different kinds of hose to stock a pretty fair hardware store. Did you decide what kind you'd like to look at?"

Millingham cleared his throat.

"Now," he said trying to seem as if he knew something about hose, "let me see! How many kinds of 3/4-inch hose have you?"

"I got eight," said Mr. Kutz doggedly. Do you want to look at 3/4-inch hose?"

"I -- now --" said Millingham trivially. "I want --"

He hesitated.

"Millingham," I said sternly. "Stop it! You can't fool me and you can't fool Mr. Kutz and you can't fool anybody. You don't know a thing about hose, and you know it, but I know the kind of hose you want."

"What kind?" said Mr. Kutz indifferently.

"He wants," I said, "the kind that looks like a snake."

"Hey?" Mr. Kutz asked.

"He wants the kind that looks like a snake," I repeated.

Millingham blushed but Mr. Kutz sighed.

"Like a half-inch snake, or a three-quarter inch snake, or an inch snake? he asked. "He ought to know; I don't. How long? A 25-foot snake or a 50-foot snake, or a by-the-foot snake? Black rubber or cotton or --"

We were right back where we began.

"He wants a hose that looks like a snake a cat will jump on and try to kill," I said. "A large female cat with gray stripes. Have you got that kind of hose?"

Mr. Kutz looked at me blankly.

"I got half-inch hose in rubber or cotton, five-ply, six-ply --"

He was going on with the list and had got to three-quarter inch hose, six-ply, when I left the store. Millingham was still there. At five o'clock his wife came over and asked me if I knew where he was -- that she had expected him home early -- and when she telephoned to Mr. Kutz's store Millingham was still there, trying to buy hose.

The next evening I went over to borrow Millingham's hose -- we never remain at outs very long -- and he met me on the back porch. He was inclined to be on his dignity.

"Brownson," he said, "last night you doubted my word when I said my cat thought my hose was a snake. Now I will show you that I told the truth. I will show you that it is rash for any man to doubt my word. Martha, please bring out the cat!"

Mrs. Millingham brought the cat to the back door and Millingham took it and held it by the neck. The new hose was on the lawn, and he turned on the faucet. Instantly, almost, the water sprayed from the nozzle with a hissing sound. Instantly he released the cat. Instantly the cat dashed toward the nozzle and leaped upon the hose, biting it with her teeth and yowling in a low but intense manner. I turned to Millingham and extended my hand.

"Millingham, "I said frankly, "I apologize."

That was a year ago. Millingham says the reason the rubber has peeled off his hose in strips, like the bark of a sycamore tree, is because I leave it lying on my lawn in all kinds of weather, and that the reason it leaks at every pore is because I let the hose kink when I am using it. I say it is because he bought cheap hose.

I was telling him last night, across the fence. Talking hose is the only way I can keep him from talking about his new baby.

"When I buy a hose," I said, "I shall use common sense. Buying a hose because it looks like a snake may be well enough, but it is not my way. I have no cat, and if I had, I would not care whether it thought my hose was a snake or not. I do not want a hose that, in a few weeks, is peeled and blistered and leaking at a thousand kinks."

"Just the same, Brownson," said Millingham, "I made you eat your words. My cat did think the hose was a snake. She did jump on it and bite it --"

My wife looked up from where she was weeding the radishes.

"Don't quarrel," said she, and just then Mrs. Millingham came to her back door.

"Oh, Mrs. Brownson," she said, as she saw my wife. "Have you any catnip in the house? Our little precious has a pain and I haven't been able to find our catnip since Augustus used it to oil the new hose --"

Instantly I knew the truth. This man Millingham had wilfully deceived me. He had smeared the new hose with catnip. I looked him straight in the eye.

"Cats!" I said "Snakes! Hose! Catnip!"

He cringed.

"Millingham," I said, and then I paused. I was going to say there were other snakes than striped ones; that there were snakes who would deceive their neighbors, making them think a hose smeared with catnip was an innocent hose that deceived a cat. I was going to say some bitterly sarcastic things that would crush Millingham as he deserved to be crushed, but I did not. It had been a hot, dry week.

"Millingham," I said, "that was a good joke. It was an excellent, clever, brilliant joke. May I borrow your hose for an hour or so?"

By Permission

We have printed Mr. Butler's story in this convenient edition for all commuters and other gardeners whether they are buyers or lenders of hose.

Draw from this tale whatever lesson you choose. "Don't borrow garden hose of your neighbors; buy a hose for yourself." "Don't try to deceive your friends; you will always get found out." "Don't make the mistake of thinking all garden hose is alike." Most of all, don't fail to get and read at once our little book

The Truth About Garden Hose

It isn't as amusing a book as Mr. Butler's, but it gives you all the necessary information about choosing and caring for hose and something about using it to the best advantage of your garden. Sent free on application to

Boston Woven Hose & Rubber Co.

Cambridge, Mass.