from Argosy

Pollywog Pearls

by Ellis Parker Butler

Something in Jim the Dip's head went "click" and he opened his eyes suddenly. Flat on his back he saw green leaves above him. Bushes! That was queer -- he never lay under bushes. A cautiously extended hand felt sand and coarse grass. What do you know!

Carefully Jim the Dip moved his head, and it did not fall off his neck. Suddenly he realized that the pain at the back of his neck, and the ache above his eyes, were gone. He raised his head and looked. This was no place he knew; this was no Chicago park. This was sand under bush willows; beyond the sand was mud; beyond the mud was a river. Across the river hills rose to a blue sky. No place he had ever seen, that was sure.

Crouching by a small fire, Jim the Dip saw two men making ready a meal. One, a grotesquely fat man with a half-moon of baldness on the back of his head, was spilling ground coffee into a pot. The other, lank and loose-jointed, was manipulating a frying pan. The men were vaguely familiar, like men seen in a dream, remembered yet not remembered.

Always neat and natty himself, Jim the Dip felt disgust, but as he looked closer he saw that while the men's trousers were wrinkled and their under-shirts faded, they were clean, Also, Jim observed that they were burned to leather-brown and loose skin peeled from the fat man's neck. Dimly Jim the Dip knew that the fat man would have pouchy cheeks and that the thin man would have a face like a gloomy horse. The fat man turned his head:

"Hy-oh, Stiff-neck! Eats ready right away, podner."

Instinctively Jim the Dip reached for the watch in his vest. He had no vest. He was in undershirt and trousers -- trousers of a suit he had bought of Kail in Chicago, but now wrinkled. His feet were bare and brown. He did not know himself or where he was.

For a moment Jim the Dip felt panic. Then he remembered the flash of the cop's gun as he ran down an alley and the thump at the base of his brain. That was after he jumped from the stolen car when it hit the milk truck. Before that he had slipped his hand into the pocket of the man on State Street. He remembered his glee when he found in the wallet twenty-four big pearls.

Jim's hand went to his waistband; he felt the small hard lumps that were the pearls. He knew now that he was himself.

"Come to grub, podner," the fat man called, and Jim went.

"Where am I?" he asked. "What's all this about? Who are you?"

"Why, gosh to glory, look at him, Hennery!" the fat man cried. "He's cured; he's movin' his head. By tucky, I told you worm-oil would do it! Didn't I tell you, Hennery?"

The Dip fell the back of his neck. He sniffed his fingers and was nauseated. Worm-oil! Fish-worms disintegrated in kerosene!

"Where is this?" he asked. "How did I get here?"

"You walked in on us, Stiff-neck," said the fat man. "Walked in like a ramrod afraid your head would fall off. And hung around. So we fed you. Gosh to glory, yes! Two months, ain't it, Hennery?"

"Was I dippy? Was I nuts?"

"You ain't been in-tirely yourself, podner. You had hallucinations and vagaries. From rheumatism in the back of your neck, I says. 'Worm-oil,' I says to Hennery. 'That'll cure it if anything will,' I says."

"Stinkin' dope, George." said the horse-faced man gloomily. "I wouldn't use it on a skunk."

"Hennery is faith-cure," said fat George unabashed. "But I say take a bottle of kerosene, put plenty of worms in it, and set it in the sun to rot -- Worm-oil cures anything. Now, you take warts --"

"Aw, warts!" Hennery exclaimed disgustedly. "Warts ain't a disease."

"He's faith-curing his warts," chuckled George, " and he's got more now than he ever had. And you're cured, ain't you, podner?"

"I feel all right," the Dip admitted, moving his head cautiously.

"Ain't afraid your head's going to fall off if you move it? If so, say so; I've got plenty of worm-oil, and more getting ready."

"I feel fine," said the Dip hastily. "I asked you where I am?"

"Why, this is Stony River, podner. Me and Hennery come up here every summer to pollywog for pearls. Twenty miles up from Riverbank."

"What do you come up for?" the Dip asked quickly.

"Pearls," George repeated. "They come out of mussels, in the river mud yonder. We pollywog for 'em."

"You pollywog? What's that?"

"It's crawlin' on your belly in the mud, draggin' a blamed old sack, and clawin' up mussels with your hands," said horse-faced Hennery bitterly. "That's what pollywoggin' is."

"Don't mind Hennery," George urged. "When his warts hurt him he gets cross. You ought to use worm-oil on 'em, Hennery."

Jim the Dip studied the pollywoggers. A couple of easy-mark rubes, the pickpocket thought, letting him hang around for two months, feeding him and doctoring him. Then he remembered something.

"I had a watch on me, and sixty dollars."

"Me and Hennery took care of them for you, but gosh, podner, we don't want no pay for nothin'. We been workin' you," George chuckled. "We set you pollywoggin' -- and dad-blamed funny you was, afraid your head would fall off. But you found some, anyway."

"Some what?"

"Pearls. Nothing to yell about -- twelve dollars' worth, maybe -- but you ought to do better now you can move your head, podner."

"Have I been crawling on my belly in the mud? Me pollywogging? Say, can you beat that? And I got pearls? Do you get many, sport?"

"Not so good this year," said George. "But there have been times. Hennery here picked up one once he got twelve hundred for."

"One thousand, two hundred dollars," admitted Hennery. "And blowed it in like a blamed fool on booze and --"

"Women?" asked the Dip, grinning.

"Second-hand ottermobiles," said Hennery sadly.

"The first one was all right only it wouldn't go," explained George.

"How much did the hospital cost you on the next one, Hennery?"

"Five hundred dollars. They took an X-ray of the insides of me; might have been the insides of a hawg for all it looked like. I wouldn't have give two cents for it. All mud-colored, it was."

"Prob'ly you had some mud-color disease from pollywogging," George suggested. "You ought to have asked them, Hennery."

"I didn't think of it at the time," Hennery admitted. "I don't let it worry me; even if I'm mud-color inside, I bleed red on the surface."

This was getting too far from what Jim the Dip wanted to know. He asked how many pearls George had found. Dozens, George told him; the biggest having been a pink one for which a buyer at Riverbank had paid four hundred dollars. It was the chance of finding a big pearl that made pollywogging so fascinating. The Dip asked if this location was a good one.

"Podner," said George, "if I knowed of a better I'd be there."

Whatever happened, George explained, they got a lot of baroques, the irregular shaped pearls used for cheap jewelry. They had a tin can full of these. The only trouble with pollywogging was that unless some large perfect pearls were found the summer earnings went for winter keep. Pollywogging could not begin until the spring floods subsided and ended when the water got too cold. The season was short.

"And where do I come in?" the Dip asked. "Partner or what?"

"It's gettin' late in the season," George said, "and me and Hennery has done most of the work. Hennery don't think it would be fair to divide what we've got into three -- is that so, Hennery? We've kepi yours separate, Stiff-neck."

"I've no kick," said the Dip quickly. "That suits me; I don't want to horn in on your stuff. You've been good to me. I'll go it alone -- if you'll let me stay with you."

"Gosh to goodness, yes!" George declared, and it was agreed. They lay back and smoked, keeping a smudge burning against the mosquitoes, and the Dip built up the plan that had formed in his mind. Here were two innocent rubes who had found and sold pearls of good value, and as their fellow pollywogger he could "find" the pearls now in his waistband. He could sell them when George and Hennery sold theirs.

Next day the three, in underclothes and trousers, rowed half a mile upriver. Here the shore sand met the river in a mud flat, soft and deep and greasy. Pollywogging was simple. George and Hennery, followed by the Dip, waded into the slimy mud and water, dropped onto their bellies and clawed in the mud for the fresh-water clams. When they had explored one spot they inched forward. Behind them the disturbed mud made smoky wakes. Now and then they found mussels; they put these in their drag-sacks and pollywogged on till the sun sank low.

As the mussels accumulated the drag-sacks became heavy. The Dip tried at first to keep on hands and knees, but he soon had enough of that. As soon as he let himself accept the mud as a thing that must be hugged he became a lively pollywog. His expert fingers, used to exploring pockets, quickly recognized the difference between a dead shell and a live mussel. He worked rapidly and was first to fill his sack, and he sat on the sand and waited.

Hennery came out of the water shivering -- possibly because of his mud-colored insides, but George was glowing. He exclaimed over the Dip.

"I told you he'd he good at it, Hennery, when worm-oil cured him. I'll give you a good rub when we get to camp, Stiff-neck."

"No more for me, George. I'm cured, I am," said the Dip.

"We oughtn't to take chances," George admonished. "'Tain't safe."

"I'll lay off worm-oil for awhile. If I get bad again --"

"Well, I've got plenty of it," said George generously.

The three pollywoggers worked up and down the river from their camp; moving the tent was too much work. Frequent change of camp was unnecessary; the river, as the season advanced, fell; mud that had been too deep below the surface became available. The three pollywoggers worked half a mile up and down the river from their camp.

They found quantities of baroques -- "slugs" -- but not many pearls of any size or of good shape, and it was not until the second week after his "cure" that the Dip ventured to "find" one of the pearls that had been hidden in his waistband. He chose a mussel and carefully pried it open, dropping the pearl into it. The mussel he put in the bottom of his drag-sack. The next morning he put his mussel harvest on top of the pearl-bearing fraud.

The pollywoggers did not open their mussels by dumping them into boiling water as shell dredgers do. There was danger of ruining a fine pearl. A sharp knife, slipped in, cut the big muscle. The meat was searched -- and later thrown in the river -- and the shells tossed on a pile. Mussel shell was worth thirty dollars a ton.

"George! Hennery!" the Dip shouted. "I got one. And, boy! a big one! Look here!" His yell echoed from the opposite hills.

"You got one?" George asked, scrambling to his feet, and as he saw the pearl he slapped the Dip on the shoulder. "Gosh to goodness! A jim-hummer! A dandy! Hennery, come and look!"

"Fetch it over here," said Hennery, but when he saw the pearl he lost his indifference. "Now that," he said, "is what I call a pearl."

"How much is it worth?" the Dip asked, feigning excitement.

"I'd give you four hundred right now -- only I ain't got it."

"Then it must be worth five hundred. Five hundred plunks!"

"And easy," said George. "Beginner's luck, gosh to glory!"

"Boy, oh, boy!" cried the Dip. "I'm going out now and try for another. Luck is coming my way. Hot doggie!"

"There's plenty of time tomorrow," George advised. "Don't get too excited; open the rest of your shells while I get grub ready."

"That's a good idea, too," said the Dip, and he went back to his pile of mussels. Five hundred dollars was a lot of money, but the Dip had a problem to solve. It would be safe enough to offer the pearl for sale when he went down to Riverbank with George and Hennery -- they had seen him "find" it, but would it be safe to "find" more of the pearls that were hidden in his waistband?

The Dip decided to find one more; it would be risky to find too many when he was the tyro of the three. With, say, a thousand dollars in his pocket, he would be sufficiently heeled to slip over to Paris or London where he might easily get rid of the rest.

The Dip had had his fill of pollywogging. He wanted now only to "find" the second pearl and sell the two. His stomach revolted at the smell of Stony River mud. He asked George when they would break camp and go down to Riverbank.

"It won't be long now, Stiff-neck," George comforted him. "The fall rains will be along gosh-to-goodness soon. I know how you feel; Hennery felt that way when he found his whopper; can't hardly wait."

"You said it, old timer, but I'll stick around."

Two days later the Stony began to rise and the Dip "found" his second big pearl. George hurrahed, but Hennery was gloomier than ever when he saw the Dip's find. He gol-darned pollywogging.

"Go on and open the rest," George said to the Dip. "Where one is there's maybe more," and the Dip picked a big shell and laid it open.

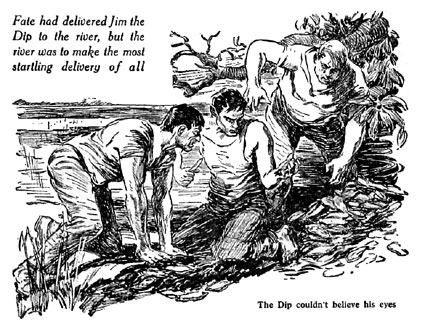

For a moment he could not believe his eyes. Cuddled in die pink meat lay a monster pearl of perfect roundness, translucently white, iridescent as an opal. Its beauty was such that even the Dip gasped. It was a perfect pearl. He knew it must be more valuable than all the ones he had stolen, put together.

"It's a pearl!" the Dip whispered. "A pearl!" He was afraid to touch it. Fat George waddled through the sand and bent to see.

"Hennery!" he shouted, "Oh, gosh to goodness to glory to gosh! He's got a wham-banger! He's got you beat. My landy landy goodness!"

"What's it worth?" the Dip asked as Hennery came to see. George took the pear! and turned it over and over in his hollowed palm.

"She's perfect, the perfectest I ever see. And the biggest. She's worth whatever you can get -- five thousand dollars; you hold out for five thousand. Don't you take a cent less."

They forgot grub. They forgot the campfire and it went out. It was not until dark that Hennery, usually always hungry, finally recalled that they had not eaten.

Next day they broke camp and began the trip down the river to the Mississippi and so down to Riverbank. The john-boat and the skiff trailing behind were loaded to danger point with shell and trappings and they went slowly. To the Dip, with his three pearls, the trip seemed interminable. They landed at Henry Moffett's boat-dock. He asked how they had done.

"Why, me and Hennery done only fair" George said, "but this young feller sure did get three beauties. And one -- gosh to glory!"

The Dip had to show the noble pearl to Hen Moffett, and George asked what buyers were in town. Moffett said Rosenzweig was at the Riverbank Hotel. He was buying anything that was offered.

But George led the Dip and Hennery first to the store of Bert Parlin, the Main Street jeweler, who now and then bought pearls. He mused long over the Dip's three pearls, and yearned over the big one.

"I can't handle anything like that, George," he said. "That's one for a big buyer. I can tell you about what it is worth. If you had two of them, matched, you could get ten thousand apiece. The one alone is worth five thousand -- easily that."

"Didn't I tell you? Didn't I gosh-lo-glory tell you, podner?" George crowed, slapping the Dip on the back. "Bert knows, he does. We'll go down and see Rosy, down at the Riverbank Hotel."

They went down to the hotel and found Rosenzweig in his room, a small man, very natty. He had been buying pearls in the town for years. He shook hands and offered cigars.

"And now we will get down to business," he said, seating himself at a small table by the window. "What have you? Anything nice?"

"You show him, podner," George urged. "Now you will see something. Rosy. Show Rosy what you've got, Stiff-neck."

From his pocket the Dip took the small box in which Bert Parlin had placed the three pearls. They lay between two layers of jewelers' cotton. Rosenzweig put a glass in his eye and bent above the pearls and silently studied them. He looked up at the Dip and paused before speaking.

"For these you will want big money," he said. "For this big fellow -- it is a splendid pearl. You wonder why I am not more excited, George? Mr. Parlin -- Bert Parlin -- telephoned me what you were bringing. So I do not drop dead from heart disease when I see it, perhaps? And these other two are fine pearls, too. You find these in Stony River, Mr. --"

"Joe Smith," said the Dip. "Yes, out of Stony River."

"A friend of yours, George?" Mr. Rosenzweig asked. "You saw him find these pearls?"

"We been pollywogging together up there," George said.

The Dip, watching Rosenzweig with keen eyes, saw him glance toward the bathroom door, and before the buyer called out "All right, Cap!" Jim the Dip reached for the pearls, but Rosenzweig struck his hand away and the three pearls rolled to the floor behind the table. The Dip did not wait; he dashed for the door and jerked it open and fled.

Marshal Coffin of the Riverbank police, leaping out of the bathroom, ran for the door. In the hall the Dip was struggling in the arms of two policemen.

Rosenzweig got down on his knees to rescue the three pearls.

"I am afraid your friend is a crook, George," he said to the amazed pollywogger. "Who he is I do not know, nor from whom he stole these pearls, but we will find out. That I had the police here I can thank Mr. Parlin, who also knows pearls. He telephoned me."

"But gosh to goodness --" exclaimed George, Mr. Rosenzweig smiled.

"We were suspicious," he said. "These two smaller pearls are oriental pearls, George. They are salt-water pearls, and salt-water pearls do not grow in Stony River -- only fresh water pearls."

"Why, gosh to glory; he's a real crook, ain't he!" George ejaculated. "And I never guessed it!"

"I knowed it all the time," said Hennery gloomily, but no one believed him. He had mud-colored insides and hated worm-oil and allowances had to be made for Hennery.