from Green Book

My Valet

by Ellis Parker Butler

I might -- for I am a writer by profession -- throw an air of mystery about this story. For a while I thought I should do so, in order to make it worth reading, but I have considered the matter carefully and I have decided that the story is worth reading anyway, and that to try to make a mystery of it would be a cheap way of drawing your attention. I shall tell it without that.

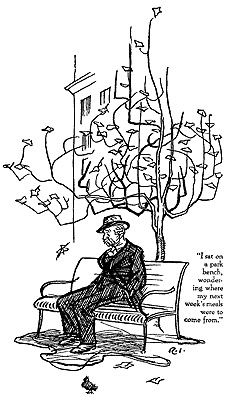

What I mean is that I might begin by telling how I sat on a park bench in Madison Square that evening, wondering where my next week's meals were to come from (I had enough in my pocket for the week then passing); and then I might tell how a man came rather quickly along one of the park paths, passed me, stopped and walked back, and accosted me. I might go on to say that he seemed to hesitate, and then said, "Why, General!" as if surprised to see me sitting there. All this is what did happen, exactly as I have told it. I looked up, and the stranger -- a man I had never seen before -- said, "What does this mean, General? Have things gone wrong with you?"

Now, things had gone wrong with me. I am an old man, old and gray, and I have been a writer all my life, like many another fellow, and my "History of Carthage" had its little sale and made its little pile of royalties, and I had my bit of success selling special articles to the magazines now and then, and I had been a fairly respectable writer in my day, and I still depended on my pen for support. The younger writers were, however, crowding me out, and there is hardly anything sadder than to come to the end of life as an unsuccessful writer with no other means of support. Hundreds of us end in the Mills hotels and similar places.

I had not fallen quite that far yet. I had my comfortable boardinghouse in a suburb almost too far from the city to be called a suburb, and I had managed to keep going. I did not owe my landlady an unreasonable amount, and until this day I had not felt utter discouragement, but I felt it as I sat on that bench in Madison Square. Until I came to New York that morning, I had believed I would carry back to my landlady enough to pay her bill. I had been for a month and a half preparing an index for a voluminous work, and I had completed it and had expected to be paid by the publisher. When I reached the city with my completed work I found the publisher had failed!

That was a hard blow. I admit I was greatly discouraged as I sat there. It seemed as if all the snap had gone out of me, and I felt tired and old and hopeless. That was the state I was in when this young man approached me and called me "General."

Now, it is not unusual for a young man to call an elder man by some such off-hand title as "General," particularly when he cannot remember the other's right name. "Hello, Colonel!" "Howdy, Governor!" You know what I mean. So it did not surprise me much when the stranger spoke to me thus. I imagined he was some young chap I had met somewhere. I told him that things had gone rather poorly with me, but that I hoped they would pick up soon. I asked him how they were going with him. It was only common courtesy to do so. He stood rather respectfully as he replied.

"After I left you, sir," he said with what seemed unusual meekness, "they went quite well with me for a while, thank you. Quite well indeed. You knew I was with Lord Abercrombie three years? A fine master he was, sir. Then I had quite a number of other positions. But none as pleasant as the one I had with you, sir, if I may say so. I was happiest with you, sir."

It flashed through my mind instantly that the young fellow had mistaken me for some other person -- some General for whom he had once worked. I was about to disabuse him of the idea when he went on speaking, and this is what he said:

"I'm right sorry to see you so down, sir, but we always did have these ups and downs, if I may make so bold as to say so, and you always landed on top in the end. No doubt you'll come out on top again, sir."

"I hope so," I said.

"I'm sure of it, sir," he replied. He seemed to hesitate. "I hope you'll pardon such a question from a valet, sir, but things haven't been bad with me at all, and I've quite a nice little place of my own just across the Square here. If --"

"Go on," I said.

"I'm out of a position at the moment was what I was going to make bold to say, sir," he said, "and if you have no valet --"

"No," I said, "I haven't." It was most absolutely true.

"I was just going to suggest, sir, that if you cared to take me on again, I would be glad to enter your employ. We need not say anything about wages at the moment; I know you'll do the right thing by me. And --"

Again he hesitated.

"If you would be so good as to make my humble habitation your own until -- until things pick up a bit for you, it would be a great satisfaction to me. I recall quite vividly the care you took of me when I had the typhoid, you see, sir. I recall a great many things. It would be a great satisfaction indeed if you would permit me."

Now, as I have said, I first thought of making a mystery of this tale, but I see no advantage in that. I might go ahead and write it, letting you think my surprisingly generous valet was a real valet and that he actually mistook me for a General Hodge he had once worked for, and thus work the tale up to a mysterious climax, when it would be discovered that he was not a valet at all, but a well-known writer of books, who had taken a notion to play a part for a while. But what would I gain by that? These are the days of realism. People like their facts served in order, like the days of the week. Real life has more interest for them than mysteries have. So I will say that from the moment my valet offered me the use of his rooms and his services free I knew he was no valet at all. I did not know just what his game was, but I knew it was a game of some sort. I knew he did not think I was any General Hodge at all, and I knew he knew I knew that. The only deception that actually deceived was that he thought he was deceiving me. He did think I thought he was a valet, and he thought I was taking advantage of the opportunity to exchange a park bench for a bed and lodgings. He thought I was saying to myself, "I don't know this valet from Adam, but he thinks I am some General he has worked for, and as long as I am a park bum and he is deceived, why shouldn't I take advantage of him?" That is what he thought.

Now, to get rid of mystery entirely, I'll tell you what I learned about my valet later. He was Roger Wentworth Rodd, the celebrated author of "Clara Turns Back" and other popular novels, and he had a good income and no troubles at all -- or had had none until the evening he met me. He had attended a tea that afternoon and someone had said, not meaning him to hear, "So that is the great Roger Rodd! He looks more like a valet than a great author." Another girl had replied. "Why, yes! Doesn't he? He is the real valet type, when you happen to notice it!" That had rankled. He thought of it all the way down Fifth Avenue.

"Valet!" he said to himself. "So I am the real valet type, am I?"

It was in his mind when he passed me, and like one of his own characters, he suddenly decided to put the matter to use. If he looked like a valet, he would write a story of a man who looked like a valet and picked up a vagrant in the park and --. He turned back and spoke to me. That is all the mystery there is, except that he was surprised when I arose and put my hand on his shoulder.

"This," I said, pretending deep emotion, "is true friendship. It is in the humble we find true hearts. Only because I see light ahead will I accept your hospitality."

"It is very kind of you, sir," he said. He gave me an up-and-down glance to make sure I was not totally objectionable as a creature to introduce to his rooms, before he went farther with the game. He seemed satisfied. "My rooms are across the Square, sir, if you care to brush up a bit before you have your evening meal."

"Thank you," I said.

"You always called me James, sir," he suggested.

"Thank you, James," I said. "So I did."

We walked in silence across the square. There was nothing I could say, for I was busy wondering how this remarkable adventure might terminate. I found the building in which my valet lived to be a marble-faced structure some eight or ten stories in height. The building was rather narrow. There was a neat but not large foyer, with a single elevator and a colored elevator man with the name of the building on his cap. It was evident that this colored man was also hall-boy, attending to the mailboxes and opening the street door. Altogether, the place was comfortable but not extravagant.

"Up, George, please," said my valet, and stepped into the car behind me. He did not speak to me as the elevator ascended. As a matter of fact, he was already beginning to realize the difficulty of the part he was playing. To me he must speak in the manner of a respectful servant addressing his master; if he did so, George would think it very remarkable. So he said nothing.

At his door he stood with his hand on the brass nameplate while he unlocked the door. I knew there was a name, for there was one on the next door (there were two apartments on each floor), but I was unable to see the name. The door opened into a small hall and that into a large living room. James -- for so I must call him -- stood to one side as I entered.

"Why, this is fine!" I exclaimed. "This is handsome, James. Do you mean to say you own all this?"

My valet hesitated. On every hand he saw things that would soon betray him if he admitted he owned the furnishings of this charming flat.

"Well, not exactly 'own,' sir," he said hesitatingly. "Own is not quite the word. The things are Mr. Rodd's things, sir."

"Rodd?" I queried, knowing I was now to hear my valet's proper name. "What Rodd, and what has he to do with all this, James?"

"Mr. Roger Wentworth Rodd, sir," said my valet. "The author, sir. He was my last master, sir."

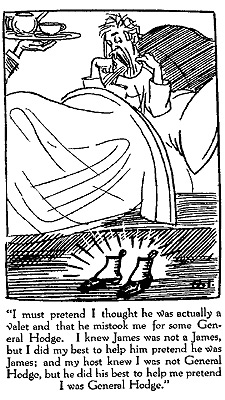

I saw that if I did not take great care, my host was going to put his foot in his mouth, as the saying is, and I knew that the moment he made any untoward slip, this mock relation of master and valet would be impossible and my host would get rid of me. In my weary condition it seemed a blissful thing to have this pleasant flat at my disposal and I was inclined to remain in it as long as I could. If I was to do that, I must overlook any slips my James made. I must close my eyes to things he would not wish me to see. I must pretend I thought he was actually a valet and that he mistook me for some General Hodge. It turned out to be a quite satisfactory way of handling matters. I knew James was not a James, but I did my best to help him pretend he was James; and my host knew I was not General Hodge, but he did his best to help me pretend I was General Hodge.

I knew of Roger Rodd and of his success, and the moment my valet mentioned the name, I recognized my valet and Mr. Rodd to be one and the same person. But I did not allow this knowledge to show.

"I see," I said. "You lease the apartment from him, James."

"Well, not exactly lease it, sir," said my valet. "Mr. Rodd is away from town at present."

"So that's it," I said. "You are occupying it while he is away."

My valet had removed my coat as I spoke, and now he brushed it carefully.

"Occupy is hardly the word, General Hodge, sir," he said. "Not occupy on my own go, as you might say. I am occupying it temporarily with a friend of mine. Henry his name is, sir. I hope you'll not mind that, sir. He is Mr. Rodd's man. In a sort of way he lets me stop here while Mr. Rodd is not in town."

Of course I saw through this. My valet was Mr. Rodd, and Henry was Rodd's valet. Henry, wherever he was at the moment, was apt to appear at any time, and he would be hard to explain unless he was explained before he appeared. My valet had thus explained Henry before Henry turned up to complicate matters. I felt, however, that it was necessary for me to appear incensed at this trick. If I was a General who had once had a subservient valet such as James pretended to be, I ought to take umbrage at the trick that had brought me to be the companion of two rascally valets, one of whom invited his friend to visit him while the master was away, and the other of whom invited his ex-master to sponge on both his friend and his friend's master.

"The idea!" I cried, trying to turn red in the face. "This is infernal impudence, James! You told me you had a place of your own, and what do I find? You bring me to share a room with you and another infernal man's man! I am a Hodge, sir, and a general, and by the great dipper, I've never been so insulted in my life!"

I did it well. It pleased my host immensely; I could see that. He pretended to cringe.

"I beg you not to think that at all, sir," he cried, rolling his hands together in true valet style as shown on the stage. "I'm quite the master here, I assure you. Mr. Rodd, sir, is deeply indebted to Henry. He hasn't paid his wage for no end of time, sir, and he quite made over to Henry the use of these rooms. So that's quite right. And Henry owes me quite a nice bit of cash, sir. I've quite supported Henry by loaning him money when Mr. Rodd forgot to pay him. So I'm quite right to feel at home here, quite as if it was my own place, sir. You need have no fear in making yourself quite at home. May I touch up your boots a bit before you go out?"

I grumbled a little but seemed to give in.

"Brush them up a bit," I said.

My self-appointed valet was brushing my boots, as he called them, when we heard the key turning in the door. James jumped up.

"If you don't mind, sir, I'll just say a word to Henry. He might be a bit surprised to find you here if I didn't say a word to him."

"Quite right," I said graciously.

"Perhaps you'd like to hear the phonograph while you wait, sir," said my James, and without waiting for an answer, he put a record in the machine that stood in the corner and started it going.

I appreciated it as a clever bit of scheming. With a brass band playing in the room -- for that was what it amounted to -- he could get Henry to one side and explain all he wished without danger of my overhearing. It was evident that he did this, for in a few minutes or less he came into the room and shut off the brass band. Henry stood respectfully in the doorway.

"This is Henry, Mr. Rodd's man, sir," he said. "This is General Hodge, Henry. He'll be stopping here a bit. I've told you often of the good berth I had with General Hodge, Henry."

"Indeed you have, sir," said Henry, "many a time."

That was a strange way for a Henry to address a fellow valet -- "Indeed you have, sir!" Neither of them seemed to notice it.

"I was telling General Hodge as how he would be quite welcome here," my James prompted.

"That he will, sir. Quite as welcome as yourself -- as anyone, sir," said Henry. "Anything I can do to make him feel at home I'll do gladly."

I eyed these two conspirators sternly. I drew myself up and threw back my shoulders, trying to assume a military air.

"That will do, Henry," I said. "You may go. James, finish my boots, please. See that you do the heels properly."

"It's like old times, sir, to hear you reminding me to do the heels properly," said my volunteer valet, dropping on his knees before me to touch up my boots. "You would have your heels brushed up even if your next step was into the muddy paddock, wouldn't you, sir? It all seems like it was but yesterday. We had our ups and downs, sir, but you always ended on top. And you will again, sir, mark my word. Often when I'm feeling blue I cheer myself up a bit by thinking of that story you used to tell about what happened to the Colonel in that battle."

"You do, do you?" I said. It seemed a safe thing to say.

"Quite so," said my valet, brushing vigorously at my left shoe. "Better than a bit out of Punch, that story was. The horse standing on his hind legs, and the Colonel grasping the brute around the neck and all the while the noise of the battle making the horse wilder and wilder. I've told it to my friends more than once, sir, but I'm a bit in doubt regarding the battle. What was the name of the battle, sir?"

"Gettysburg," I said promptly. It made no difference what battle I named. There was no battle and no story of the Colonel, and I knew it, and he knew it.

"I thought it was Spion Kop," said my James somewhat reproachfully, and I as if I was indeed an impostor trying to live up to a real General Hodge's past. I cleared my throat.

"It was Spion Kop," I said. I knew that pleased my valet. He thought he was playing with me.

"And the Colonel's name. Odd name, sir. What was it now?"

"You ought to know," I said. "I told you often enough."

"Higgins, wasn't it, sir?" he asked.

"May have been," I said.

"Or wasn't it Gilderstern?" he asked.

"Something like that, or Higgins," I said, pretending to be greatly embarrassed.

"I thought, sir," said my James reproachfully, "you always said it was Geddub. Don't you remember, sir, that that was the point of the whole tale? That the more you tried to make the Colonel come to order, the more you shouted 'Geddub! Geddub!' and the horse thought you were urging it on, sir."

"Oh, that story!" I exclaimed. "I was thinking of the other one -- the one about Higgins and Gilderstern at Gettysburg. You got me confused for a minute, James. Thanks. That will do."

He remained bent over my feet a full minute; I could see he was chuckling. When he arose, his face was quite serious. It must have been a task to control his mirth so completely. He pretended to be nervous over what he was about to say.

"I hope you will not think me impertinent, sir," he said, "but now that I'm back in your employ I trust you will let things go on just as they used to go when I was with you before. You were always very kind to me then, sir, and let me loan you a bit of cash when your remittances were slow. I hope I may do the same now, if you are not in funds. A few hundred, let us say, until your luck changes. I have put quite a snug bit by from time to time."

"Well, James," I said as grandly as I could. "I don't want to hurt your feelings."

"Thank you, sir," he said humbly. "Perhaps a hundred?"

"A hundred would do nicely," I assured him.

My valet went into the next room and returned with five twenty-dollar bills and handed them to me. I saw immediately that Roger Wentworth Rodd was a good sport, willing to pay for his fun. I folded the bills and slipped them into my pocket carelessly.

"You know what I'll do with them, James," I said.

"Of course, sir. The old system still, I suppose?"

"The old system. Yes, indeed. It always wins in the end, James."

"So I told you, sir. You always come out on top."

"Yes, yes! My stick, please, James."

I had no stick, but I had seen several in the hall as I entered. My valet hastened to get me one.

"I'll not be late tonight," I told him. "A bit of dinner and then home."

"You'll not try the system tonight, then, sir?"

"Not tonight. I'm tired tonight. Dinner, then back here and a bath. You'll be here to give me a good rub. Then bed. After that you may go out if you wish."

"Thank you, sir," said my James.

As I had expected, I saw Henry shadow me when I left the building. I knew well enough that Mr. Rodd would be interested in knowing how I spent that hundred dollars -- if I meant to go and not return again. I made an effort to make the shadowing easy for Henry, but that was hard, for he seemed to have a knack for losing me. Several times I had to wait until Henry caught up with me. Once he came bolting around a corner and bumped full into me.

I chose a cheap restaurant where my own funds would be ample to pay for my dinner. I ate at leisure and then strolled slowly back to Mr. Rodd's rooms. When I entered the foyer, the all-around man was at his desk. He arose and walked to the elevator.

"Mr. Rodd," I said. "He is in?"

In spite of himself the all-around man grinned.

"No, sah," he said, trying to keep a sober face. "Mistah Rodd gone Souf fo' some stay. His man, though, Gennul, tol' me to let you come up any time. Yas, sah!"

"Ah, indeed!" I said. "Rather peculiar, isn't it, letting two valets use his rooms this way?"

"That ain't none of mah business," said the negro, but he chuckled.

"Then it is none of mine," I said.

Thereafter the three of us settled down to a simple domestic regime. By some complicated criss-crossing of questions and answers I forced my valet to say just what my system of making money was. He tried to get me to say, but I stubbornly resisted. It might have been cards, or it might have been the stock market, but he decided to make it the racetrack. Those were the days when racing was in full sway around New York, and when it was no more trouble to place a bet than to get a haircut. I had not bet on a horse race since I was a young man, and I was loath to attempt it with Rodd's money, but it seemed part of the game he wanted me to play. I kept putting him off, telling him I was waiting for a chance to make a killing. As a matter of fact, I knew no more about making a killing than I did about flying.

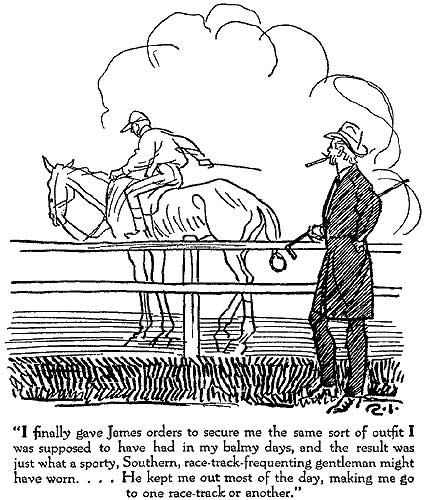

Rodd seemed to enjoy his imitation General hugely, and spared no trouble or expense in playing the part of a faithful valet. He pretended to regret that I had not the same handsome outfit I used to support in my palmy days, and he described it to me article by article. I finally gave him orders to secure me the same as I had had, and the result was just what a sporty, Southern, racetrack-frequenting gentleman might have worn.

As for himself, he became each day more a valet and less an imitation. I suppose he had Henry coach him while I was out. He kept me out most of the day, sending me to my luncheon early and making me go to one racetrack or another, according to where the racing was being done. I usually got back in time to dress for dinner. This gave Rodd time to do his two thousand or twenty-five hundred words of writing, which was his usual amount for a day, and to attend to any other matters he had on hand.

As I have said, he urged me continually to try my "system" at the track, and I as continually put it off. I bet a little every day, a dollar or two on each race, seldom losing over five dollars a day and sometimes making ten or so. I did not do this because I was interested in that form of gambling, but in order that I might tell of it when I returned. Two weeks passed in this way. I was enjoying the whole experience hugely, and I could see that Rodd was enjoying it. Henry was the first to cause trouble. He came to me on the street one evening.

"I hope you'll pardon me, sir," he said, "but it is too much for any man to believe, that Mr. Rodd is a valet. I can't believe you believe it, sir."

"I don't, Henry," I said. "I knew from the first moment he was not. I have known ever since I entered his apartment that he was Mr. Rodd."

"I've nothing to say about your sponging off him, sir," said Henry. "He makes a wonderful lot of money out of his books, and what you cost him is of no importance, I dare say. If you have no feeling about sponging off him, it is not for me to say anything. I'm thinking of myself, sir."

"And what are you thinking about yourself?" I asked.

"I'm that fond of Mr. Rodd, sir," said Henry, "it would be quite a blow to me to have to leave him. But I can't stop on with him much longer the way I am overworking, sir. I was hired to be valet to one man, and now it is two, and it is going to be three."

"Three?" I exclaimed.

"Three, sir. Yourself, for all the principal part of the work, pressing trousers and all that, I have to do, and Mr. Rodd -- for of course I have to do for him, sir -- and now the third coming."

"Third? What third is coming?"

"That's just it, sir," said Henry. "It is the complication and all that is so wearing. I'm not a bright man, like Mr. Rodd, able to do these things and not feel them. It is no end of a strain to try to remember that Mr. Rodd is not Mr. Rodd but James. And now this third is coming."

"What third? I asked you what third?"

"That's just it, sir. It will be most confusing to me. You know Mr. Rodd is writing a book about all this. Getting along well with it, sir, too, as he told me himself. 'It's fine, Henry,' he told me, 'if only the General would try his system,' he says. 'What the General don't know about racing is the most laughable business in the world,' he says to me, 'and just writing down what he tells about his racetrack experience is making this the funniest book of years. He beats 'David Harum,' and when he plays his system and tells me about it, I will have a chapter that will make the book a best seller,' he says, 'but he's slow getting at it. It will take more urging,' he says, 'and in the meantime I've got to have more complication in the plot. So I'm going to bring Mr. Rodd back,' he says."

"Going to bring Mr. Rodd back!" I cried.

"Just that, sir," said Henry miserably, "and I don't see how I can stand it. There will be you, sir, being the General, and Mr. Rodd being James, and someone else being Mr. Rodd, and it will be more than I can manage. The telephone will be the worst, sir."

"The telephone?"

"When there is a call for Mr. Rodd," explained Henry, "to know whether it is for Mr. Rodd or the Mr. Rodd that is not Mr. Rodd. You see what I mean -- whether it is for James that is Mr. Rodd or the somebody that is not Mr. Rodd but is being Mr. Rodd. It is hard enough keeping things straightened out -- by which I mean tangled up -- now. I can't stand much more of it, sir. I really can't. And once Mr. Rodd, which is James, sir, gets the idea of complicating a plot, there is no telling where he will end. You may have read some of his books, sir, and the complications are enough to make one quite dizzy, but he made them up out of his own head. But now that he is going to have it all happen, and in a two-room apartment, with bath, of course, and the amount of pants I'll have to press, to say nothing of shadowing you to fill in the chapters -- well, I can't stand it. My head won't stand it."

"And what is it you want me to do?" I asked.

"If you would just try your system at the races," said Henry, "it would satisfy Mr. Rodd, I think. He'd let you go, then, and I would not have to go."

"Well, Henry," I said, "I'll tell you. I've enjoyed this little experience myself, but I'm not the park bird Mr. Rodd thinks me. I'm a writer myself. I have a commission to revise Dunkel's Elementary History of the United States, and it is time I got at it. I'll play my system and get out of the complication."

Henry grasped my hand gratefully.

"Oh, thank you, sir," he cried. "It takes no end of a load off my mind."

The next day, in the train that carried me to the races, I tried to think of a "system" that would be worth putting in Mr. Rodd's amusing bestseller. I supposed race-goers did have some sort of system of play, but I did not know what it was, and could not imagine, but a happy thought struck me. The name Mr. Rodd had conferred on me was Hodge, and my system should be Hodge. That ought to be nonsensical enough to suit Mr. Rodd. He ought to make a good chapter out of an innocent old duffer picked up in a park and forced to create a "system" and in desperation creating one that was Hodge.

It was not a complicated system. The money Mr. Rodd had forced on me now amounted to five hundred dollars. I divided this into five equal parts of one hundred dollars each. These I would bet on the races, the first hundred on the first horse to run with a name beginning with H, the second hundred on the first horse running with a name beginning with O, the third hundred on the first horse running with a name beginning with D, and so on for the G and the E.

In the first race that day there was a horse called "Humming Bird," posted at 3 to 2, and I played "Humming Bird" for my H and lost my hundred dollars neatly and quickly, "Humming Bird" finishing about sixth. No O appeared until the fifth race, and "Orestes" fell at the third hurdle and never finished at all.

That evening I told my amateur valet what my system was and how it had worked so far. He pretended full faith that I would, as he always said, "come out on top," and I could see his eyes sparkle with joy as I explained the "system." It was just the sort of thing he wanted for his book.

The next day I found "Donald Dare" and lost my hundred at 5 to 1, and my James sympathized with me abundantly but urged me on.

The third day's trial of my system ended my racetrack experience. G showed on the card as "Golconda" and seemed a sure winner at 2 to 1, and was a winner, and after the race I received the three hundred dollars from the bookmaker with a feeling that even the most silly systems do have a chance, and I bet my remaining hundred of system money on a bay mare listed as "Eclat."

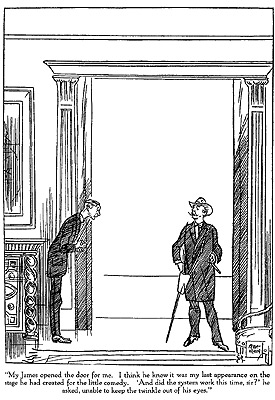

When I went up in the elevator to Mr. Rodd's apartment that evening, I was quite ready to lay down the mantle of General Hodge and be myself again. My James opened the door for me. I think he knew it was my last appearance on the stage he had created for the little comedy. Perhaps Henry had told him.

"And did the system work this time, sir?" he asked, unable to keep the twinkle out of his eyes.

"James," I said, "you have been a faithful valet. I cannot praise you too highly. It breaks my heart to have to part with you."

"You're not going to give me the sack, sir?" he asked.

I put my hand in my pocket and handed him a small roll of bills.

"I'm not going to send you away owing you money, at any rate, James," I said. "There are the five hundred dollars you advanced. And one hundred for yourself, James."

He stared at me.

"It is all right, Mr. Rodd," I said. "You have been as faithful a valet as any James could be. You deserve a tip."

He laughed.

"So the cat is out of the bag, is it?" he said good naturedly. "I'll say that you have been a kind master, too. And how about the famous system?"

"It works just as well as in the old days," I said, laughing. "I always come out on top, you know. G won two hundred dollars."

"And E?" he asked eagerly.

"E?" I said with assumed carelessness. "Why, E won also. I had a hundred dollars on E. E was 'Eclat' and a 25 to 1 shot. I won twenty-five hundred dollars on E."

Mr. Roger Wentworth Rodd held out his hand and shook mine warmly.

"Great!" he said. "Great! That's just what I want for the climax of my twelfth chapter!"