from Fruit Garden and Home

Home Grown Whetstones

by Ellis Parker Butler

When I get up tomorrow morning to attend to my business -- which happens to be writing for magazines -- the one big tool that I have to use is the day -- the day that begins when I open my eyes and stretch and say, "Oh, gee! time to get up again!"

I have a typewriter and some pens and pencils and writing paper and ink and such things but they don't count for much; the day is the big tool. I'm going to use that day to carve something worthwhile or I'm going to chop out something that won't be worth shucks -- some no-good affair that looks as if it was chopped out with the dull end of an axe. And I've discovered that whether what I turn out is good or bad depends on what sort of day I tackle the job with -- a dull day or a keen, sharp, happy day. I never did have much luck whittling with a butter-knife.

And it is the same with you. If you get up in the morning -- no matter what your business is -- and find that the only day you have on hand to use in your business is a one of these dull insipid days with no more edge than a rolling pin you might as well go back to bed and let the mold grow in your hair. That's all the good that day will ever be to you. No matter whether your business is running a bank or running a house a dull, stale day that has a brown taste in its mouth is never in this world going to be a keen-edged tool.

And when a man gets to be my age, and is like a safety razor blade that has been used eighty seven times on one side and then turned over and used eighty seven times on the other, his days are going to be mighty dull days and considerably in need of a whetstone if he don't look out. His life is going to get lull of tiresome cobwebs and musty smells and saw wood like a piece of tinfoil.

Along about then, if he has not been wise enough to begin sooner, it is time for a man to go out into his backyard or his empty acre and begin raising homegrown whetstones to sharpen his dull days on.

A while ago I was writing an article on "Ruts" and I wrote: "A garden -- whether flower or vegetable -- is a delightful avocation for any man, if he enjoys it. When a man becomes interested in tulips, or in irises, or in dahlias -- or in all three, for they arrive in different seasons -- he is a made man. Life suddenly becomes an entirely new and more interesting matter. The man who reaches the point where he sneers: 'Vonderschnuck! Vonderschnuck for tulips? Why, I wouldn't have one of that dealer's bulbs in my garden if he gave it to me!' is on the way to eminent success in his regular business life. A fad of this sort, any live avocation, not only clears a man's brains of cobwebs, but it sends a sweep of clean air through it."

I would have liked to write more about that then, but I was in a hurry and had to go right on to something else because my taxes were due and I did not want the editor to waste time sending back the article with a letter saying it was all right but that he could not send a check until I had gone over the article and cut eight thousand words out of it, so I stopped there and changed the subject.

The truth is that I am a member of such a fine and dandy country club with such an excellent golf course that I am posted every six months for non-payment of dues, and I have played over the course just once. I get as much fresh air -- the same number of breaths per minute, exactly -- and as much good exercise and more happiness right out in my backyard trying to fool a couple of thousand tulip bulbs into thinking I know which is the right end to stick in the ground, and when it comes to conversation I do get a lot more enjoyment out of telling my wife what a mistake she made in planting the petunias so close to the marigolds that they both have to stand pigeon-toed, than I do in having a golf partner tell me why my game is so different from Harry Vardon's. Golf is all right, and other things are all right, but I can grow more first-class whetstones in my garden than on the golf course.

By whetstones, I mean, of course, that clean, clear interest in something of my own that keeps every day bright and keen. Plugging an axe into a tree all the year round, and year after year, dulls it, and plugging your life at your business all the year round, dulls your life in the same way. I don't have to tell you that; you know it. To do his or her best a man or a woman needs something to whet his days. Or her days. As the case may be.

Whether a man plants fruit on a ten acre lot or grows tulips or radishes between the fence and the back porch, the prime good quality of this sort of homegrown whetstone is the same -- a fruit tree and a garden is always on the move; it is always hopping along just one jump ahead of you and keeping you on the keen and interested go. It does not, like a golf course, lie down and snooze until you sort of lazily think it is about time to go over and wake it up. The minute you put a spade in the ground that garden takes a running start and shouts "Tag! You're it!" and scoots off through digging time and planting time and thinning-out time and weeding time and pruning time and picking time and you get so interested and excited and have such delightful bug problems and fertilizer puzzles and swell up so big when your petunia measures an actual five inches across the top -- from Maine to California, as you might say -- that you are keen to get at your work in the morning and keen to get back to your garden later on.

And if you do catch up with your garden and head it off and get in front of it you find that it scoots between your legs and it is time to dig up bulbs and bag them up before you have quite got rid of the weeds. And about the time you can lean back and say "By golly! we had a good time this summer, my garden and I!" along come the seed catalogs and the bulb catalogs and the tree catalogs and you get a pencil and begin to figure.

And if you do catch up with your garden and head it off and get in front of it you find that it scoots between your legs and it is time to dig up bulbs and bag them up before you have quite got rid of the weeds. And about the time you can lean back and say "By golly! we had a good time this summer, my garden and I!" along come the seed catalogs and the bulb catalogs and the tree catalogs and you get a pencil and begin to figure.

"Here," you say to your wife, "is a new tulip that ought to be worth trying -- 'Crown Prince Joachim Boomzedoom, Early Darwin; Winner of the large tin medal with six points, Harlem, 1922. This is undoubtedly the most noble tulip yet seen in captivity. Stem four feet tall, as stiff as a steel fish rod; foliage deep green and even greener than that yet. Blossom so softly pink that Queen Wilhelmina wept like a child when she saw it and so large that one of our gardeners fell into a bloom and has not yet been recovered'."

"What is the price?" your wife asks.

"Well, of course, it is something exceptionally fine," you say. "The price is not bad considering."

"What is the price?"

"Hum! Well, I did not think of getting a thousand, you know --"

"What is the price?"

"Well, five dollars a bulb," you say, being forced to it.

"Oh!" says your wife. She pauses. "Well, it might be worthwhile to have one or two just for novelty. A few really nice varieties always give one such pleasure. I think you had better get one or two."

And then she says:

"And just hand me that iris catalog, John, while we're talking flowers. It's under that magazine. There's a new iris I want to show you -- I don't think it is so very expensive for such an extra fine --"

She gets it, of course. The catalog. And the iris, too.

Half the dullness of life is due to the fact that a husband and wife have so little to talk about; so little that is interesting. Christopher Columbus might come back from discovering America and keep a wife interested an hour or so but most of us don't have time to go off discovering Americas every day. I don't. But I can come in almost any morning and give my wife a most interesting bit of news --

"What do you think?" I ask her. "That purple columbine that was showing yesterday is full out today!"

So we go out and see the purple columbine and admire it. And talk about it. It is like having a new and beautiful baby every morning. When you own a garden -- your very own garden -- you have something that is important. You pick up the morning paper and read that a tidal wave has wiped out Timbuktu and drowned 199,999 natives, and you may say "My! my!" or you may merely yawn, but if your wife conies in and says, "John, the Jones's dog or something has broken that seedling dahlia you were meaning to exhibit at the flower show," you know what real tragedy is.

All this whets your day and whets your life. I'll leave the talk of beauty and of thoughts in the garden to those who are more accustomed to write of them. I hope I enjoy beauty -- whether it is the beauty of a tulip or of a plum -- as much as the next man, but I'm talking of the other good a garden does one. I'll leave out the appetite it gives you and the fresh air, too. If all these were cancelled and wiped away the value of garden in giving a man or a woman something to work with --something in which he can become thoroughly interested -- would make it one of the most valuable things in the world.

Our garden is, considered one way, in four parts. My whole place is 100x180 feet, and on this is a fairly large house and a large stable. There is a driveway and a path or two. Between the barn and the rear fence is a strip about as wide as a man could straddle and there my wife has her fernery -- very nice; lots of ferns of all kinds. In a space between the driveway and a path is the shrubbery. Shrubbery along one edge of the place, also, and elsewhere. Very nice; quite a lot of it. Numbers three and four get mixed up quite a little; number three is my wife's garden and number four is my tulip outfit. They shake hands more or less. Some of the tulips may stake out a temporary homestead in one place and a little later some of my wife's flowers may move in there, and the next year her iris may foreclose a mortgage on the whole strip. Gradually everything is getting located where it belongs. I think, meanwhile, I have talked more words regarding the location of my tulips than regarding the education of my eldest daughter and certainly ten times as many as I have ever spoken regarding the state of Europe.

This is because a garden gets to be a mighty living part of any man's life. He may, if he likes that slant, hire a man to dig the garden. He may, if he chooses, hire a man to do nearly all the work. He may, if he is plutocratically heeled, hire a regular gardener. The garden is his garden, nonetheless.

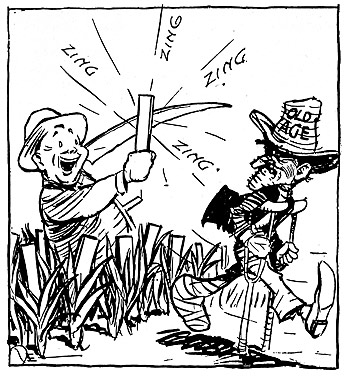

Personally I like the digging in the ground, the trimming of my own grass path's edges and planting the bulbs and all the rest with my own hands. When I have a trouble I like to go out and tell it to a tulip -- to a red-and-yaller tulip; they don't mind a few troubles. I like to go out and sit on the grass and dig up self-heal and sand-grass and dandelions and get one square foot clear and then a square yard clear. I find that when I have an idea that will not line itself up in proper form for an article or a story I can make it line itself up most quickly and most satisfactorily by storing it away in the back of my brain and going out in the garden for a while with a trowel. In the sweet thoughtlessness of garden messing the idea begins to talk and twist and get legs where it ought to have legs, and arms where it ought to have arms, and a head and a face and -- zing! -- it is a proper idea, all ready to be put on paper and sold for a million dollars or less. Mostly less. But even less than a million dollars is worthwhile.

Dallas Lore Sharp seems to favor bees rather than a garden. He says bees are pure poetry and adds, "So in my going to and fro I carry a hive of bees -- a hive to give to every man, for the health in it, the happiness, the philosophy, the poetry. A hive of bees is a big gamble, too, and more rest and distraction, not counting the stings, than any other plaything I know."

I'll not quarrel with that. Have bees if you don't want a garden. Or have bees and garden both. Have the bees in the garden, if you want to. Personally I prefer goldfish in the garden, for no goldfish has ever stung me on the back of the neck and several bees have, but that is merely my own feeling in the matter. The big thing is not to overlook the fact that both the bee and the garden are always busy and give us what we need more than we need food -- rest and distraction.

This fall I'll have something over 2,000 tulip bulbs to put in the earth. For about 1,400 of these I have to dig new ground, take out the sod and the grass roots, put in manure, scoop 1,400 little nests for the tulip bulbs to sleep in during the winter, letter considerably more than one hundred labels, figure out a color scheme so that brick reds will not shriek at crimsons. My homegrown whetstones begin to bear fruit as soon as the catalogs come.

Last Spring I exhibited something like sixty-five tulips at the Garden Club's tulip show in our town and did not get a single prize. I don't care. Or, at least, I say I don't care. I say, "Pish! I don't care for a prize anyway; I grow tulips for the fun of it." And then I say, "And anyway, it was no fault of mine. I ordered Paffenzoom's bulbs in May and the agent lost my order and, just when the ground froze, filled my order with a lot of junk from Vonderschnuck. And do you want to know what I think of Vonderschnuck's bulbs? I wouldn't have one of that dealer's bulbs in my garden if he gave it to me! No, not if it was a Crown Prince Joachim Boomzedoom, Early Darwin!" But I'll bet I win some sort of ribbon this next show! I'll win one if I have to put in a layer of manure twenty five feet deep and water the tulips with pearls dissolved in champagne -- and you know how impossible it is to get champagne nowadays.

As soon as a man or woman gets a garden under way the whole landscape changes. There's no more "What's this dull town to me, Robin Adair?" business. Where he or she saw nothing but dull town before he and she now see bird baths, a trellis wall that certainly must be repeated in our back yard, and "I never did see an iris like that; we certainly must have one!" and they see gardens that make them ache with envy and gardens that make them swell with pride because their own is really so much better, and that stupid Brown and dull Mrs. Smith suddenly become mighty interesting and worthwhile people because they can tell us what is the matter with the asters and how they managed to get such amazing dahlia results.

And all this, as I said before -- and don't mind saying again -- clears a man's brain of cobwebs and sends a sweep of clean air through it. The best place to grow whetstones with which to sharpen your joy of living is in your own garden.