A Footnote on the Yellow PerilBy Mark Schreiber A thoroughly detestable chap, this Dr. Fu Manchu. And he seems to possess more than one life, thanks to a slightly obsessed writer by the name of Cay Van Ash. London—Winter, 1911. An evening gloom enveloped the rows of run-down buildings on the banks of the Thames, close to the area known as the West India Docks. Shivering in the damp chill, a young Englishman stood in wait at the mouth of a narrow alley. After having stalked his prey for months, the young man felt he was close to success. A journalist who dabbled in fiction, he was acting on a tip from an informer that the elusive "Mr. King"—reputed to be an opium dealer and master Chinese criminal based in London's seedy Limehouse district—would be coming that evening to a nearby office. His vigil continued for 15 ... 30 ... 45 minutes. He was almost ready to abandon his quest and head for the safety and warmth of a pub when, suddenly, he glimpsed the headlamps of a limousine moving down the street.

From his hiding place in the recessed alley, the Englishman froze. The car halted and he saw two passengers descend. The first to alight was a tall, dignified Chinese, attired in a fur-collared overcoat; he was followed by an Arab girl. Light flooded out from the opened door of the building, etching the face of the Chinaman into the young Englishman's memory for all time. As he was to record in his writings afterwards, "I knew that I had seen Dr. Fu Manchu! His face was the living embodiment of Satan."

Few writers of fiction have ever actually

seen their

most famous character, let alone under such

exotic circumstances. Yet for Sax

Rohmer, the pseudonym of Arthur Henry "Sarsfield" Ward, this hair-raising

glimpse of an obscure Chinese—shall we say,

businessman?—was to inspire the creation of one of the

most enduring characters in popular English

literature: The Yellow Peril

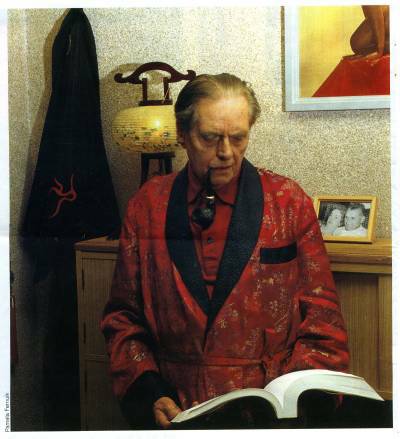

incarnate, Dr. Fu Manchu. The strange story of the budding young author and his evil character is one of the highlights of Master of Villainy, a highly stylized biography of Sax Rohmer. The book owes its start to an afternoon in 1935, when 17-year-old Cay Van Ash climbed aboard his bicycle in Sussex to seek an interview with his literary hero at Rohmer's country home. "We talked about his work, about his stories," reminisces Van Ash between puffs on his pipe. "I just asked to meet him because I admired him as a very great English writer, and as I had aspirations to be a writer myself, I thought that I could learn something . . . about his technique." Rohmer was not generally known to spend time with his fans and admirers, and as far as Van Ash recalls, his meeting with Rohmer was the one exception. "The originality of the thing appealed to him, apparently, so he agreed to see me. He volunteered to help me with my work . . . (and) started going over all the amateur manuscripts that I wrote in those days. He even suggested that I go and stay with him for a year or so. I stayed fifteen months." From that beginning, their friendship grew. Rohmer passed away in 1959, but years later Van Ash was called back from Japan, where he has been residing since the early 1960s, to collaborate with Rohmer's widow Elizabeth on the colorful writer's biography. Master of Villainy was published in 1972. Happily for dyed-in-the-wool fans of Dr. Fu Manchu, Cay Van Ash did not allow his boyhood fascination to remain dormant. From his home in rural Saitama Prefecture, the scholarly Waseda instructor has already penned two Fu Manchu novels (published in the U.S. by Harper & Row) and is currently at work on his third. That he is singularly qualified to be doing so must be credited to his ongoing six-decade love affair with Rohmeresque fiction.

Photo: Pamela Fernuik

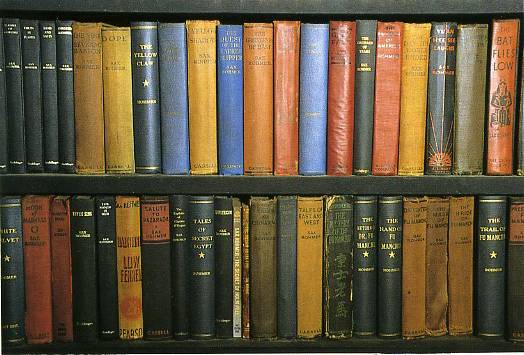

"My scorpions—have you met my scorpions ? No? My pythons and hamadryads? Then there are my fungi and my tiny allies, the bacilli. . . And we must not forget my black spiders, with their diamond eyes—my spiders, that sit in the dark and watch—then leap!" Sax Rohmer (1883-1959) wrote over 50 novels on fantasy and the occult, but is best known for his most colorful villain, Fu Manchu— a household word who also gave his name to a particular style of drooping mustache. Handsome, energetic and highly imaginative, Rohmer was one of the most popular and financially successful authors of his time. Like many novels of the day, the Fu Manchu stories first appeared serialized in magazines, in this case the October 1912 issue of the long-defunct British periodical The Story-Teller. While final chapters in the 10-part series were still being sold on the newsstands, the entire novel made its debut in book form in June 1913 as The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu. (The U.S. version, under the title The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu, was to follow later the same year.) Today, some 40 hardcover and paperback editions later, the book is still in print. Rohmer's stories were often considered shocking by the polite standards of the 1920s, but his imaginative style and literary craftsmanship were seldom in dispute. He frequently went to outrageous lengths to lend authenticity to his fiction, once even smoking opium so he could better describe its euphoria. (It merely made him sick.) He was a virtuoso at developing nefarious uses for "unknown" poisons and noxious creatures such as centipedes, snakes, lizards—and the above-mentioned spiders. Fu Manchu was not left to rest on his laurels in books. As early as 1923, filmdom had him putting damsels in distress—only to be rescued from his clutches by his nemesis, the intrepid Scotland Yard detective Nayland Smith. The vile Oriental villain was portrayed in movies by the likes of Warner Oland, Boris Karloff, Henry Brandon, Christopher Lee, and—in a spoof on the genre that turned out to be the actor's last film—Peter Sellers.

Book sales and Hollywood contracts notwithstanding,

the character should have

produced financial success for its creator, but

in fact the Rohmer’s financial status fluctuated

wildly.

Whimsical and moody, Rohmer required a hard push from his better half to

produce. According to one source, Elizabeth

would provoke fights with her husband to put

him in a gloomier frame of mind, upon which

she would lock him in his room, not letting him

out until he

produced the required volume of work. Although Sax Rohmer did not create the sinister Oriental, he was the first to achieve major literary success; to say that Rohmer was widely imitated in his time may be something of a gross understatement. Boys' dime novels and pulp fiction in the 1920s and '30s spawned a host of cheap, sometimes comical imitations. There was Ssu Hsi Tsu ("Ruler of Vermin"), who tried to unite all the criminals in the U.S. under his control; the keen-eared Wu Fang ("Dragon Lord of Crime and Emperor of Death"), who planned to poison the entire population of New York; and Dr. Yen Sin ("saffron-skinned wizard of crime"), star of a 1936 pulp magazine. Nor was the gentle sex ignored. In addition to Rohmer's later creation, Sumuru, there was Fah Lo Suee, the daughter of Fu Manchu. In their various forms and guises, these queens of crime have come to symbolize the perennial Dragon Lady, a figure who appears everywhere from Milton Caniff's Terry and the Pirates comic strip to the more recent Madonna & Sean Penn film flop, Shanghai Surprise.

To understand the mentality behind the Yellow Peril phenomenon, one must consider the times. As Van Ash explains, "There was a great deal of apprehension in England . . . concerning the Chinese, because these people were running all the gambling and drug businesses (in Limehouse). They were baffling the law authorities because they were doing it all in this foreign language that nobody spoke and applying their own unique criminal methods. Then of course there was the fact that only 10 or 12 years earlier, in 1900, you had the Boxer Rebellion, in which quite a lot of foreigners were murdered. Couple that with what I call the real origin of the well-known Yellow Peril—the fear of what would happen if all these millions of Chinese, whose ways were totally alien to ours, should decide to get together and gang up on us one of these days." Fu Manchu had his own reasons for wanting to orchestrate mayhem among the white race. One legend has it that his wife was slain during the Boxer troubles; he also blamed the Europeans for the overthrow of the Ch'ing (Manchu) dynasty in 1911, an event which set off his fanatic pursuit for a lost cause. Strangely enough, it was not Fu Manchu which prompted Van Ash to turn to fiction, but another popular character from the past—fictional sleuth Sherlock Holmes. "Until I did Ten Years Beyond Baker Street," explains Van Ash, "I had no intention really of picking up these characters or following on. But what I observed at that time was that Sherlock Holmes has been paired with the most unlikely people, ranging from Sigmund Freud to Dracula. And I thought, well certainly someone is going to pick on Fu Manchu before long. "I have tremendous respect for Sax Rohmer's works, and I don't want them to be treated badly. And I think I can do it better than anybody else, because I have the necessary background. So I thought that if anybody's going to do it, I'd better." Finding time to write between teaching jobs at Waseda and his other work here in Japan, Van Ash retired behind the beaded curtains of his second-floor study to write, in longhand, his first full-length work of fiction. Ten Years Beyond Baker Street was published by Harper & Row in 1984. In the narrative, Sherlock Holmes is brought out of retirement to join in the chase for the evil warlord. Most of the story, which takes place in 1914, is situated in Wales. Like vintage Rohmer, the novel combines the fanatical assassins of the Si Fan—an underworld group controlled by Fu Manchu—with weaponry ranging from high-tech ultrasonics to a Gila monster. As the author likes to put it, a Fu Manchu story is less of a "whodunit" than a "how'dhedoit." This kind of authenticity doesn't come easy. Many modern Sherlock Homes parodies (known in the literary trade as Sherlockiana) contain material which deliberately contradicts the facts as stated in previous stories. "I think that's a completely dishonest thing to do," Van Ash complains. "It's not fair at all. I think that you have to go along with the story as it was." In this regard, Baker Street was particularly difficult, because it required Van Ash to work very hard at limiting himself to the backgrounds of characters used by both Conan Doyle and Sax Rohmer. Still, one never gets the feeling when reading Van Ash's books that one is reading a parody. Indeed, it is a tribute to the author's craft that one must look quite hard to find evidence that the story wasn't actually written back in the days of spats and bowler hats. In this age of gigabytes and megatons, one wonders, how can a writer manage to preserve an authentic Edwardian literary style? One must work at it, apparently.

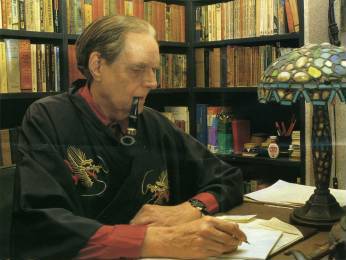

Van Ash's technique is a simple (if somewhat

difficult) one to abide by. "I try not to read

anything published later than 1940," he says,

"because I don't want my vocabulary affected."

"That includes newspapers," he adds.

"Otherwise, too many words will creep in, and

make me stop

and wonder, did people really use those words then, in the 1930s?" For his encore, Van Ash decided to write his second novel about Fu Manchu exclusively. With his Korean-born wife Okchon in tow, he spent an exhausting 18-day sojourn through Egypt searching out background material. To keep things in proper perspective, he traveled up and down the Nile armed with a guidebook to Egypt published in 1914. Returning home, he parted his beaded curtains, donned his dragon-embroidered kimono, and sat down once again to complete his second work of fiction.

The Fires of Fu Manchu, which went on sale last autumn, brings back Nayland Smith, Dr. Petrie and the familiar cast of Rohmer bad guys. Set in Egypt during World War I, it features Fu Manchu's devious daughter, a half-human half-ape creature trained to do her evil bidding, and a deadly ray-gun, a sort of primitive laser. Determined to see the war continue in the hope that the white race will exterminate itself, the devil doctor steals a top-secret weapon that would end the war right out from under the noses of the British, who were preparing to demonstrate their superior technology to a German general. "It's hard to say just what it is; I don't think anybody has successfully discovered the mystique of Dr. Fu Manchu," Van Ash commented. "The strange thing is that he captivates everybody, even in this generation. As soon as they read their first Fu Manchu story, they get hooked. |

||

|

Fu Manchu

Cocktail

|

||

|

"I suppose he has a great nobility about him. I don't think it any longer has anything to do with the Yellow Peril. It's just because he's colorful and exotic. The fact that he's Chinese is quite irrelevant, really." Does Van Ash find things getting easier, now that he's hit his stride? "No," he sighs. "I don't. In fact, I really find it rather more difficult. I always feel I sort of have to live up to the standard that I previously established. I'm always worried that I may fall short of my own standards." And as for any future writing projects? All Cay Van Ash is saying at this point is that Fu Manchu still has a few tricks up the flowing sleeves of his yellow silk gown. MARK SCHREIBER is the author of countless magazine pieces that have appeared in publications here and abroad. Copyright © 1988, 2006 Mark Schreiber. All rights reserved |

||