|

|

from Saturday Evening Post

What Would the Boys We Were Think of Us Now?

by Ellis Parker ButlerThe other day, among some old papers, I ran across the photograph of a rather nice-looking little boy, and when I turned it over I found written on the back, "Ellis Parker Butler, about 1876, aged 7." That did interest me, you may well believe. There we were -- the boy I was and the man I am -- face to face, and if we wanted to we could say what we thought of each other.

For a man to see a photograph of himself as he was forty-six years ago is not so interesting as it would be to see a photograph of himself as he will be forty-six years from now, but it is something. Forty-six years from now I may be a wabbly old gentleman ninety-nine years old, taking nourishment out of a soup spoon; or I may be standing in line at the window of the supply department to ask for a new string for my golden harp; or -- but I hope not -- I may be looking at a thermometer that registers 2697 degrees above zero and saying to the man next me:

"It looks as if it would be warmer today if we don't have some rain, and I'll bet a million to one we won't."

No one can guess what a photograph of himself taken forty-six years from now will show. If there is anything in this transmigration-of-souls business, as the old Druses believed, a twelve-dollar-per-dozen cabinet photo of me taken forty-six years from now may show me as a Rocky Mountain goat or as a Peruvian llama or as a plain but dignified ox. On the whole I don't believe I will care to be an ox unless the pasturage is fair to middling and the work light, but I would rather have my photograph show

me an ox than as something in the fourth-dimensional-space plane -- say, as a transparent parallelepipedon marked A, B, X and Y at the corners. For a man who has always been rather proud of his looks, a photograph that showed him as nothing but an invisible whiff, represented by the formula 7A+3B(-Z+2X), would be quite a comedown.

My Photograph in 1968

Even if the photograph showed me resolved into my constituent chemical elements, I don't believe I should care much for it. I should hate to go over a lot of proofs with my family and have my daughter say: "I don't like this one at all. The H2O hardly shows at all, and the carbon and iron are so prominent they make papa look like the inside of a last year's stovepipe."

Even if the photograph showed me as an angel -- and that is almost more than I dare hope -- someone would probably study it a while and then say:

"Yes! Yes, it is a good likeness; but why didn't you wait until you were through molting? Or did you need insect powder?"

On the whole, though a photograph taken forty-six years from now would be interesting enough, I think I like the one taken forty-six years ago, even if the boy in it does not look at me with enthusiastic pride.

This seven-year-old boy in the photograph is sitting in the photographer's plush chair, sideways and cross-legged, with his right elbow on the back of the chair and the fingers of his right hand spread out like the rays of the sun. I can still feel the moist hand of the photographer as he lifted one finger after another and put it exactly where he wanted it to be, exclaiming, "There! Good! That's fine!" Then he jumped back to his camera and hid under the black cloth and took a look at me and jumped back to me to move one finger an eighth of an inch south by southwest.

"Now, ready! Don't move! Ah! The proofs will be ready Friday."

His name was J. P. Phelps, Artistic Photographer, Muscatine, Iowa, the card says. I have a memory that he was short and hairy. The interior of his gallery was hot and smelled like an oversterilized hospital. When you were posed a large iron clamp grasped the back of your head. In those days the photographer was as fussy as the undertaker, and being photographed was almost as fearsome as being undertaken. You did not decide on the spur of the moment to be photographed, and dash up and have it done and dash down again. The family began talking about it in June, and during July and August held consultations with the neighbors, trying to decide which photographer to go to. All of September and part of October was spent trying to decide whether to have a dozen carte-de-visite size or half a dozen of the newfangled cabinets with the jaggy edges.

Short of the Mark

By that time the photographer chosen had moved to Davenport or Asia and the neighbors had to be called in again; and when a new photographer had been chosen Christmas was at hand, and the photographer could not promise to have the pictures done before New Year's Day; so the whole business was put off until spring.

I am sorry to say that when this boy in the 1876 photograph faces me he has a somewhat resentful look.

I hope this is partly due to the iron clamp that is gripping the back of his head and gradually pulling three hairs out by the roots; but I don't know that I blame him much anyway. He is probably looking me over and sizing me up, and it makes him feel sick. Sitting there on that plush chair the young Ellis is a pretty fine-looking kid. He has a nice forehead -- a mighty fine-looking forehead -- and his skull looks as if it had a good brain capacity. He is just the sort of boy to grow up and be President Harding or Frank A. Vanderlip or the Bishop of Eastern Pennsylvania or some other great or wealthy or famous man by the time he is fifty-three.

A boy like that, seven years old in 1876, might be Herbert Hoover or governor of Iowa or the president of Columbia University, in 1922. He might even be a new sort of Napoleon Bonaparte and president of the Confederation of the World, or chairman of the board of trustees of the International Consolidated Hook and Eye Company, Incorporated; or even -- if things went right -- a blacksmith. A boy like that has a right to look forward to being almost anything noble and great by the time he is fifty-three. He has every chance that Edison had, or Thackeray, or any other man. Even Jesse James was only a seven-year-old boy when he was seven years old.

What worries me is what that boy would think if we happened to meet. It is hard to fool a seven-year-old boy; it is easier to fool your doctor.

This young fellow in the 1876 photograph is evidently all dressed up in his Sunday clothes. No boy I ever knew in Iowa ever looked that neat and tidy on a weekday unless he was going to a party or to be photographed; he could not have stood it -- it would have killed him; he would have expired in misery. This boy has on a broadcloth suit with gold buttons, and his shoes are polished -- except the heels -- and he has his Sunday-go-to-meeting tie on and his Sunday stockings and just everything!

I remember those buttons; they were lovely buttons, beautiful and bright. There was a row down each lapel and a row on each cuff and a row at the side of each knee. No matter where the boy sat, he arose with two or three fringed tidies hooked onto the buttons, and he had to be plucked before he was allowed to go forth. I remember that broadcloth suit. The boy's mother made it; she bought the broadcloth and cut out the suit and sewed it and bound its edges with silk braid. It was a noble suit, and its only fault developed when she took it to the little German tailor to be pressed. She had no iron heavy enough to crush down the seams. The tailor said it was a nice suit and would wear a long time. "Only, maybe," he said, "it wouldn't be so easy to hold such a big boy upside down by the heels already when you should want to brush him."

Sunday-Go-to-Meeting Finery

He said that because the boy's mother had happened to cut the cloth with the nap running the wrong way, but I cannot remember that she ever did hold the boy upside down by the heels to brush him. Probably she took him out of the suit before she brushed it. The little German tailor may not have thought of that; he may not have been very bright. Or she may have brushed the suit before putting the boy into it; there is more than one way of doing a thing.

I remember that suit so well because it was such a big event in that boy's life. First the broadcloth had to be selected, and it is enough to drive one crazy to decide whether it shall be blue or black or brown. Then the broadcloth had to be sponged and pressed. Then it had to be cut out, lying flat on the table, with the shears eating through it, allowing for seams, the shears going "Creak! Creak!" as they bit their way, and with the boy's mother stopping suddenly with a catch of the breath in sudden fear that she had cut out two backs to the trousers and no front. She had!

It seems to me that the boy spent several years -- long and torturing years -- standing on a stool and trying on that suit. He had it pinned on him in separate pieces, and tried on in basted sections and in every stage of development. Sometimes he tried on one sleeve and sometimes both sleeves; sometimes one pants leg and sometimes two pants legs at a time. Then it would be the coat without the sleeves.

"Please, please!" the boy's mother would beg through a mouthful of pins. "Do please hold up your arm!"

Then she would gather up a fold of broadcloth and stick a pin in it and, inadvertently, into the boy somewhere, and when he yipped she would sit back and say she didn't know what she would do if he could not stand still a quarter of a minute at a time; she was just about discouraged with the suit as it was. It must be admitted that it is difficult for an amateur tailoress to cut an armhole to the right size when a boy keeps his arm clamped down tight and giggles every time he is touched, except when he is crying; but after a boy has tried on a suit a couple of thousand times he begins to think it is monotonous. He wishes he was an Indian and could wear a blanket and a couple of ready-made feathers.

I remember the boy's blue-and-gray-striped wool stockings too. His grandmother knit them, but she did not put in the sandbur tips and other stickers -- they were in the yarn when she bought it. The boy did not have to try on the stockings; all he had to do was stand and sigh while he held the hank of yarn as it was being wound into a ball. This was a lot of fun, like chopping kindling when you want to go fishing and bringing in wood when you want to play marbles, and it was a pleasant change from trying on broadcloth coats. When the boy was tired holding out his arms to have armholes cut it was a relief to hold them out while yarn was being wound off them.

I remember the necktie too. It was, I believe, the most beautiful object the boy ever possessed. In a photograph the full elegance of the tie does not appear, the color effect being lost entirely; but the tie was what, in 1876, was called a Roman stripe. The Romans certainly liked their colors numerous and bright. When an architect began to build a Roman stripe he was fair to all the Romans. If one Roman loved scarlet he put it in, and if another doted on orange yellow he put that in, and if the next liked grass green in it went. It was first come, first served, but any time a Roman discovered a newer and brighter color the weaver ran it right in and was grateful. The only times a Roman stripe weaver was sad was when no one was discovering new and more gorgeous color, and then he wove in a little good honest black to show his sadness. The black sort of set the colors off and made them more showy. The boy's tie had fringe on the ends, and he admired the tie with pure unblemished admiration. It was worth it. No matter what else the boy wore, he was all dressed up as soon as that tie was around his neck, and everybody within a mile knew it.

When I picked up this photograph of the boy I was forty-six years ago I thought I remembered the gold buttons; but I could not be sure, so I got a magnifying glass, and sure enough, they were the very same buttons, with a gold knob in the middle and little gold dots scalloped around the edges. Then I looked at the shoes, but they brought back no memories; I suppose that was because they were polished -- they did not seem natural. I seemed to remember the shoestrings, wrapped twice around the ankles and tied in a hard knot; and the mud on the shoe heels -- good old Muscatine clay that stays where it is put -- but the fancy loops of stitching around the shoe tops meant nothing to me whatever.

Revelations of the Magnifying Glass

It is remarkable how faulty one's memory is. The only way I can account for it is on the theory that perhaps they were not the boy's shoes at all, but borrowed shoes. The metal tabs on the ends of the shoe strings seem to suggest this; they are all there, and I cannot remember the boy's shoe strings ever did have tabs on them one day after he got them. A large portion of the boy's life was spent wetting the ends of shoestrings in the manner most convenient and then twisting them into points that would reluctantly poke through the eyeholes. But perhaps these were brand new shoestrings, purchased to be photographed in.

I was having a grand time with my magnifying glass. I looked at the striped stockings to see if I could discover any of the stickers, but they were not in sight -- they were inside, sticking my legs of course. Then I raised my magnifying glass a fraction of an inch, and my eye came to the bottoms of the pants, where they met the stockings. Here was another thing I had not remembered: The edges of the boy's beautiful broadcloth pants were worn threadbare, and had been overstitched quite carefully; but, even so, little edges of white lining showed through and wisps of lining ravelings hung down here and there. The Sunday suit was on its last legs.

I could work up something rather pathetic about that, I believe; something about the dear little lad trying so bravely to look at the camera -- and at J. P. Phelps, Artistic Photographer, Muscatine, Iowa -- and not let on that his little heart was almost broken by the thought of the fringe on his pants -- the boy's pants, not J. P. Phelps' pants -- and I could make gentle mothers and strong harsh men hide their faces in their hands and sob until they all rushed down to the post office to send the little boy pairs of pants; but, for one thing, the pants would not fit me now; and, for another thing, that little 1876 boy never felt any feelings of the sort. The only Sunday-pants thoughts that boy ever had were that it was a dog-gone shame he had to wear them on a weekday. No, the only way to get pathos out of the photographs of those seven-year-old boys we were is to wonder what they would think of the way we have lived up to their expectations.

Looking at it that way I do feel rather sorry for all those nice little boys we were. They were such hopeful little fellows. When he is seven years old, or about then, a fellow begins to speculate quite a lot on what he will be when he is a man. He does not think of the man he will be as exactly the same person as himself. He is only a boy, but this other fellow is going to be a man. He begins to look around among the gods and heroes to pick out the sort of men he hopes to be. He takes a look at father and decides that father is a fine man, far and away the finest man he knows -- you can't beat the loyalty of a seven-year-old boy -- but he has to admit that father is not absolutely perfect. He has to admit that in one or two little matters George Washington probably did surpass father a wee mite. Father is father of course; but it cannot be denied that John L. Sullivan had a wonderful right arm. There is usually, it is true, a spare half dollar in father's pocket when the circus comes to town, but -- with the utmost loyalty to father -- one has to admit that in finance Rothschild and Croesus and the Count of Monte Cristo certainly had the goods. Father is father, but when a young fellow is daydreaming of his future he is compelled to remember that there were such men as Christopher Columbus, Buffalo Bill, Abraham Lincoln, Leatherstocking, Robert Fulton, Ole Bull, Patrick Henry and Cal Towers, the champion snare drummer of the United States.

A young man of seven, looking far into the future, has a right to expect great things of the man he is to become. He has a right to expect the man to be a credit to him. Of course the boy's perspective may be a little faulty at the moment. The boy I used to be, after questioning whether he would prefer to have the man be a second George Washington or the World's Unrivaled Premier Bareback Rider, decided that properly to fulfill his destiny and meet the approval of his soul he must be a blacksmith.

I am ashamed to say it, but I confess I have failed the young man there. I am not a blacksmith. The sort of blacksmith the young man had in mind was one with a large quantity of black hair on his arms and a complete jungle of it on his exposed chest. His main occupation would be whanging a piece of white-hot iron with a heavy hammer while he let the sparks fall on him with no more concern than if they were snowflakes. Now and then he would spit into the water tub and shift his quid to the other cheek. To vary the monotony he would occasionally straddle the lower leg of a horse, holding its hock between his knees while he pressed a red-hot horseshoe to the sole of the hoof. A whiff of blue smoke would then spurt out with a sizzle, perfuming the air with a delicious odor of burnt horn. When the horse moved the blacksmith would shout at it sternly, using a few well-ripened words; if the horse was a mule he would shout louder and the words would be riper.

At times the blacksmith would lean indolently against his forge and slowly pull the knotted rope of the huge bellows, turning now and then to pat the coals with his pincers and then addressing some witty words to the small boy looking in at the door, such as "Well, bub, what do you think your folks call your name by when you're at home?" or "Well, sonny, how's your coppery-optics today?" or even that more amazingly brilliant query, "Well, Johnny, how does your corporosity seem to sagasitate this morning?"

Presently, because of his admirable qualities, six men in frock coats and high silk hats would arrive and make the blacksmith President of the United States, commander in chief of the Army and superintendent of the Episcopal Sunday school. The blacksmith would then put a for rent sign on his shop, buckle a sword around his waist, don a Knights of Pythias hat with a long white ostrich plume and go down to Washington, D. C., to veto the bill prohibiting boys from playing marbles for keeps. When he died his funeral procession would be three miles long and have four brass bands, and a grateful nation would erect a statue of him, showing a kind but stern countenance and a pair of trousers that were too long and too loose.

If I had to go back to 1876 today and face the boy I was I know he would look at me with a stare of utter unrecognition. First he would stare; but when he realized I was he, he would burst right out crying

"No! No!" he would sob. "You don't even look like a blacksmith!"

"But wait!" I would beg. "Wait until I tell you --"

"I see!" he would exclaim. "You were not worthy enough to be a blacksmith, but you have done the best you could -- you are President of the United States."

"No; but --"

"Then you are commander in chief of the Army. Well, you've not entirely betrayed my trust."

"But I'm not --" I would stammer, trying to think of an excuse.

"Not commander in chief?" the boy would cry. "Stop! You have already broken my heart, but perhaps you can save one or two of the pieces. Tell me you are at least something worthwhile; do not keep me in suspense -- tell me you are at least superintendent of the Episcopal Sunday school!"

And I would have to tell him I was not even that -- not even a pirate or a two-gun man or a fireman in a red shirt; not even a bishop or a millionaire or a senator. Then, probably, he would give me one final look of reproach and go out behind the woodshed and eat a green apple and die.

Watching Yourself Parade

If a man has a seven-year-old son he hates to have that son think he is a failure, and he will stoop to a lot of subterfuges to avoid destroying that boy's belief that he is a hero; but hardly any of us give a thought to the boy we were and what he would think of us. We owe something to that boy; we owe something to the faith he had in us.

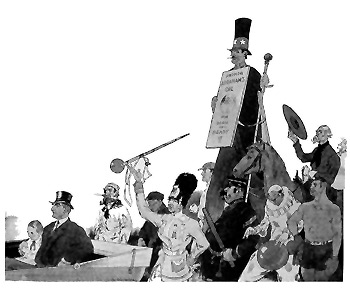

I wonder how we would feel if all those little boys we once were, who so trusted us to be the best we possibly could be, should get together somewhere and look us over. Suppose they were all lined up along the sidewalk -- thousands of those seven-year-olds -- as if it was circus day and the big parade was expected to heave into sight any minute. Little Ellis Butler would be there, and little Warren Harding, and little Herbie Hoover, and little you, and little Sammy Smith, and little Johnny Jones, and all the little seven-year-olds we once were.

There we would all be, eating double-jointed peanuts and pink-and-white popcorn nervously, and leaning out as far as we could, craning our necks and now and then running to the middle of the street to see if we could catch the first glimpse of us as we came marching down the street in the procession.

Suddenly from far up the street would come the first weird tootle of the steam calliope; and then, nearer, the first blare of the brass band at the head of the parade; and one little boy would jump up and down and shout, "Here they come! Here they come! I see 'em!"

Then the head of the procession would come in sight,

and every little boy would be ten times as excited as before. Imagine not having seen yourself for years and years! I would turn to you and say:

"You just wait until you see the man I've become! You'll see something worthwhile, I bet you! I'll bet I'm splendid -- just awfully noble and rich and kind and famous and honest and everything!"

"Yes, but you just wait until you see me!" you would cry. "You'll know me the minute you see me! I'll be the governor or a millionaire or the head of a big corporation, or something elegant."

We boys on the sidewalk would not have the least doubt about some things. The men we had become would all be fine, strong men with our heads held high -- brave and rich and successful. It could not be otherwise.

So along comes the brass band, tooting and thumping, and all the little boys that we were stand on tiptoe and dance with eagerness and excitement. We're going to be a proud lot of boys, I bet you!

Brass band at the head of the procession goes by. And who is this in a big automobile, with a silk hat? Little Warren Harding on the sidewalk gives a loud cry of joy and rushes into the street. He's happy! It is true that the man he has become has no red-white-and-blue sash around his chest, and he does not wear a gilded sword, and he has no cocked hat with a Knights of Pythias plume; but he is President of the United States, and that is something. So little Warren runs along beside the automobile and big Warren sees him and opens the door of the automobile and helps him in and they hold each other's hands and the parade moves on.

Giving Little Ellis the Slip

And now the rest of us on the sidewalk are eager! These are the big men, at the head of the parade, and we scan each face eagerly, hoping one of these men is the man we have become. And here and there, up and down the sidewalk, a boy exclaims joyfully and runs into the street and grasps a man's hand -- he has found himself. And they go marching by. All the successful men march by -- the men who are thoroughly worthwhile. That part of the parade comes to an end.

And the rest of us now? We are so anxious we grow tense and stand in utter silence and just stare and wait. You -- well, I don't know about you -- but I am there in my broadcloth suit, with my shoes all polished except the heels, and I have on my striped stockings and my beautiful Roman-stripe tie; but I do not give them a thought. I'm looking.

It is a rather mixed lot, this remainder of the paraders. Here is one man with a bloated face and a blackened eye and mud on his ragged clothes, and a little boy in a neat blue seersucker suit and a chip hat with a blue sailor ribbon -- a sweet little boy if ever there was one -- sees the man and recognizes him and begins to cry. He puts his hands over his face and backs away from the edge of the sidewalk and turns and runs.

His heart is broken, all right, and he is going around back of the woodshed to eat a green apple and die. And the man he has become does not look at him; he is ashamed to.

And presently I begin to be nervous as I stand on the edge of the sidewalk. So few of the boys are running into the street to take the hands of the men they have become; so many of them do not recognize the men they have become; so many of them are hiding their faces and hurrying away to find woodsheds and green apples.

And, marching down the street, I see from far off the wistful small boy in the broadcloth suit with the brass buttons and the striped stockings and the lovely Roman-stripe tie standing on the edge of the sidewalk and waiting for me. I don't know what you do, but I edge over toward the other side of the street and slip out of the parade and down Sycamore Street and through the alley and take the first train out of town.

I should hate to meet that boy. It would be mighty hard to explain the why of a lot of things.

Here and there in America a man suffers from what Mr. Freud calls an inferiority complex. As I understand this, it is something like a bilious bullfrog that gets into your cranium and keeps croaking away, night and day, "I'm no good! I can't do it! What's the use trying?" until you believe the little liar. That is a bad sort of amphibian to have in a cranium. It would be better for a man to fill his cranium with water and put goldfish in it. Whatever may be said against the goldfish's lack of conversational ability, one has to admit that it doesn't croak discouragement all day. The goldfish sings no songs of despair. If I had a goldfish that sang songs of despair I would wring its neck -- if it had a neck.

The trouble with most Americans -- if we have any troubles -- is not an inferiority complex, but inferiority satisfaction. This is a new term, and I invented it myself; but it is a good one, and will probably be used in all the new textbooks.

It is a little difficult to explain, like Mr. Einstein's theory of relativity and why it is that your collars always come back from the laundry with saw edges; but in a general way, when a man has an inferiority satisfaction it means he is content to sit in the sun in the bleachers all his life, when he might, if he hustled a little more, have a box just back of the home plate, and a season ticket.

In the book I am writing, entitled "The Inferiority Satisfaction, or Sticking in the Mud While the Other Fellow Goes by on Horseback," the whole business is explained, with diagrams and maps and dotted lines, and the formula on Page 87 shows the thing at a glance. The formula is to this effect, if no worse:

+-----------------------

| 4(O+2EZ) - 21(Z-3H)

| -----------------------------

| ($1,000,000-L) - y(A.D. 1876)

V This, you will see at a glance, gives the whole matter in a nutshell, because if y(A. D. 1876) represents a young-feller-me-lad sitting on a doorstep in 1876, it must be perfectly clear that he will never get very far if he loafs on the job too much after he is old enough to shave. If, then, we let O represent the seat of his trousers, and Z an honest day's work, and H an hour, the formula shows that if a man is satisfied to sit around three hours a day on O, loafing or daydreaming, Hades -- represented by L -- will be frozen over long before he has one million dollars -- represented by $1,000,000 -- or anywhere near it.

Why a Ship Rocks

Mr. Sperry has invented a gyroscope to put in the bow of a ship to stop the ship from rolling during storms at sea. For some time people have considered the sideways rolling of a ship more or less of a nuisance, especially after meals. When a man is on a ship and the ocean comes up and tilts the ship over to port until the tip of the mainmast hits a porpoise on the dorsal fin and another section of ocean comes up on the other side and rolls the ship over to starboard until the tip of the mainmast can pick up a jelly fish, even a sailor is apt to feel perfectly disgusted. It is also disheartening for a gunner on a battleship to aim at an enemy and have his vessel roll over until the muzzle of his cannon points at the bottom of the sea and he shoots a very expensive shell at an entirely neutral mermaid, and -- next shot -- have the ship roll back so that the next shell plugs a hole in the Milky Way.

The difficulty in stopping the rolling of a ship has always been the water. If a ship would stay on dry land it could be braced up and it would not roll; but quite often thoughtless persons take ships out on the ocean, and there is an awful lot of ocean; almost more than is needed. The result is that when the waves begin to roll there is an awful lot of waves, and when wave after wave -- each with thousands of tons of water in it -- comes rolling up against the ship, tipping her over and tipping her back again, it would seem that she just had to roll.

A man would think that with a huge ship rolling from side to side, and thousands of huge waves giving her a push, nothing on earth could steady her; that a gyroscope big enough to steady her would have to be bigger than the ship.

That is not so; not at all! The gyroscope Mr. Sperry uses to keep a ship steady, with her masts straight up in the air in the rollingest kind of sea, is -- in proportion -- no bigger than an apple in a barrel. He fools the ocean.

Living Inch-by-Inch

The trick is easy when you know it. He does not let the ship begin to roll. Mr. Sperry's gyroscope could no more stop a ship from rolling when it was rolling rails under than a consumptive cowboy with a lasso could stop the Transcontinental Express. That is not the idea at all. He puts the gyroscope in the ship and waits for the first wave. One wave can hardly roll the ship at all; it can only start the rolling. The rolling has to be worked up as a girl works up a swing. The gyroscope can handle that first wave easily, so it does just that.

The first wave slides harmlessly under the ship and the ship is still steady. Then along comes the second wave, but the first wave had not budged the ship, so the second wave is only another first wave, and the gyroscope can handle that all right.

That is how the gyroscope works; it does not have to fight all the waves of the ocean at once.

It takes the waves one at a time, kills the effect of the first one, and waits for the next and kills that, too. It never allows the ship to begin to roll.

The failure or near-failure who sits down to look back over his years often cannot see how his life could have been a success. The successful man, looking back, sees his life as a clean, taut white cord reaching from the seven-year-old boy he was to the man he is now; the other man sees his life as a loose and knotted yarn, all kinks and ravelings and tangles -- an awful mussy thing -- and he does not see how he could have kept all that length of yarn taut and white and clean.

My notion, after having studied gloomy bullfrogs and silent goldfish and gyroscopes and inferiority satisfactions, is that the way to live is inch-by-inch and day-by-day. One inch at a time we can handle, and one wave at a time, and one day at a time.

The lazy man is never lazy by the year; he is lazy by the day. Tomorrow he is going to get busy and hustle, but today there is no hurry; he'll just take things a little easy today. And that is one day. Before he knows it the days are a lifetime. And there he is! The first thing he knows he runs across a photograph of the boy he was when he was seven, and then he is ashamed of himself.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 2:37:58am USA Central