|

|

from Success Magazine

Our National Game

by Ellis Parker Butler

For almost one hundred years the grandest minds of the United States met in Congress, year after year, and wore frock coats that looked like year before last, and made speeches, and wore their massive brains to shreds trying to hold the States together, and at the end of the year the outlook was worse than ever before. Never in the history of the world had statesmen tried to drive such a bunch of wild-eyed mavericks in harness as our solemn-jowled statesmen were trying to manage, and they made a botch job of it at last. About half the team kicked over the traces and dashed for liberty, and there was a grand mix-up along in the sixties, and half of the team had to be clubbed back into harness. It was an awful mess.

Saving the Union in Billing's Barnyard

And all the while, during all those years when the sad-eyed orators were uttering long words and cellar-deep sentiments, and proposing compromises, and bringing to light musty old aphorisms of government, a lot of kids in the lot back of Billing's barn were proceeding to unify the United States into a great nation, one and indivisible. This was during the hoop-skirt period, and the first thing the lads had to do was to gather the discarded hoop skirts and chuck them out of the way over the fence into Billing's beet patch.

Then they put a brickbat gently but firmly on the soil and called it "batter's base," and taking a fence picket for a bat, and a ball of Aunt Susan's stocking yarn for a ball, they knit the States into a permanent Union. At the very moment when Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun were standing in the forum and ripping the stitches that held the flag together, two great Americans -- "Reddy" Figgis and "Smitty" Schmidt, aged fourteen and fifteen -- were playing "one old cat," and saving the Union in the only way the Union could be saved.

Until we had a national game it was silly to speak of the loose group of States as a nation. The people had too much time in which to talk politics, and whenever they talked politics they became angered, and whenever they were angered they wanted to secede, or knock spots off each other. There was no one great unifying spirit. There was too much "Maryland, My Maryland" and "Yankee Doodle," and not any "Casey at the Bat." All the animus that is now directed at the umpire class was allowed to foment into sectional feeling. A man from Baltimore and a man from Boston could not meet and talk in-curves; they had to talk slaves. Imagine the benighted state of society!

It is a wonder that the nation lasted until baseball arose in its might and strength to make of us one great people!

You may be told that baseball arose at the close of the Civil War. This is a canard started by those who still wish to corrupt our nation. The fact is that the Civil War petered out because baseball had been invented and the people had no more time to waste in quarrels. They wanted to go to the game. Thousands of Southern soldiers went home to practice in-curves, and the Northern hosts, fearing that the South would create an unbeatable array of pitchers, and thus monopolize the pennant, hurried matters a little and brought the war to a close.

A national game is the greatest unifier in existence. After a free American citizen has sat for a whole afternoon on the sun-baked bleachers, and has yelled his throat to rags, and the southpaw pitcher of the visiting nine has shut out the home team, the free American citizen is in no condition to go out and stir up party strife.

All he wants to do is to cast a few bricks at the umpire, and get into some cool spot where he can talk it over with another citizen. He does not look forward to starting a rival republic. He wants to see what the evening paper has to say in way of excuse for the home nine.

Nothing has set America so high in the estimation of foreign nations as the adoption of baseball as the national sport. If a foreign spy wanders into America, seeking to fathom our real inwardness, and sees a game of baseball, any feeling of contempt for our newness gives way instantly to awe-struck admiration. At his first glance baseball is to him a mystery, and it remains a mystery to him. He sees thirty thousand men and women suffering the tortures of the lower regions on hot grandstands. He sees a man pick up a small white ball as hard as a pine knot. Facing him is another man who holds a smooth but deadly club in his hands. Behind this second man is a third man whose face is hidden behind a birdcage. Suddenly the man with the ball raises one foot in the air and shows the man with the bat the sole of his shoe. The man at the bat sees that there are spikes in the sole of the shoe and it angers him, and he raises his bat to throw it at the man with the ball. But, ah, ha! the man with the ball is too quick for him. He throws the hard, white ball at the man with the bat with all his strength. The man with the bat waves defiance by swinging the bat in the air. The ball proceeds. The batman never flinches! Will the ball kill the man, or will the impact crush the ball? But, see! The ball finds man unflinching; the ball is panic-stricken; the ball dodges around the man; the ball is lost, buried in the huge leather chair cushion that covers the hand of the birdcage man behind the batman! "Strike one!" says the umpire. Thirty thousand cheers. Why?

The Bewilderment of the Innocent Spectator

Again the pitcher-man raises his foot and casts the ball. This time the batman stands motionless and mute. Again the ball dodges when it nears him. But this time the batman does not attempt to hit the ball with the bat. "Strike two!" says the umpire. Thirty thousand cheers. Why?

A third time the pitcher-man raises his foot and casts the ball. This angers the batman. He raises his club. When the ball comes near him he reaches out and hits it hard. He seems to know he has done wrong. He drops his bat and runs. Thirty thousand yells of wildest triumphal joy! Why? Why does the mass of mankind cheer the strike one and the strike two and the safe hit alike? The reason is that the same period that has seen the education of professional ball players has seen the education of professional baseball-seers. The raw American citizen who takes his seat at a ball game for the first time feels as he would should he drop into the Metropolitan Opera House and find himself hearing Wagnerian opera from a seat in the midst of seasoned German opera-goers. He hears a language that is new to him. The man at his right can tell more about the first baseman's peculiarities than he could tell about the manners of his own wife. The man at his left has trouble remembering the size collar he wears, but he can name every man in every club of both the major leagues, tell the age of each, give the complete table of batting records off-hand, and recite, item by item, every feature of every game played on the home grounds during the last five years! That is why baseball is our national game. We love the game, not because we are Chicagoans and the Chicago nine wins, nor because we are Pittsburgers and the Pittsburg nine is winning, but because we are educated in baseball and like to see a good game played by the best men in their field that can be found in the world.

I remember being on a Chicago streetcar, sitting beside a nice old lady in mourning, a year or so ago. She was nervous and kept glancing at me, and then glancing away again. It made me uncomfortable. I thought she took me for a pickpocket or some other bad man. Finally she could contain herself no longer. She leaned over. "Excuse me," she said, "but have you heard yet how the Cub's game came out?" I hadn't, and her face fell, but in a moment she saw a possible opportunity for consolation. "Well," she asked, "can you tell me who they are putting in the box today?" How was that for a gray-haired grandma? In Chicago they all talk baseball, from the cradle to the grave. Up to three o'clock in the afternoon no one talks about anything but the game of the day before. From three o'clock on the only subject is the game that is being played. The school child who cannot add two apples plus three apples and make it five apples with any certainty of correctness can figure out the standing of the Chicago nines with one hand and a pencil that will make a mark only when it is held straight up and down.

Why it is a National Game

Theoretically, any nine men or boys of fairly able body can join together and be a baseball nine. If this were not so, baseball could not be our national game. A national game must be played with cheap sporting articles, and the cheaper things may be, the more national the game becomes. Tennis, with rackets at five or seven dollars each, and expensive nets and courts and balls, proved a failure when it was the national game of France. It was fine for the elite, but it was no game for the hoi polloi , and the result was that the hoi polloi met in the tennis court and voted the heads off the tennis crowd. But baseball can be played with a bat that costs five cents and a ball that costs a nickel, with old bricks for bases and any vacant lot for a diamond.

If eighteen ragamuffins cannot be gathered together in one neighborhood to form opposing "nines," the nines can get along without fielders and six men will do on either side. If twelve boys can not be got together, the game can go ahead with shortstop and third baseman omitted, and if necessary the pitcher can play the three bases as well as pitch, and thus two men on either side can form a nine. Less than four boys can hardly form a desirable game of baseball, but two can form a "battery" and practice by the day with joy and pleasure. Such a game is something like a national game! If it had been in existence at the time, Thomas Jefferson would have included the right to play baseball as one of the articles of the Declaration of Independence.

A Game that is a Game

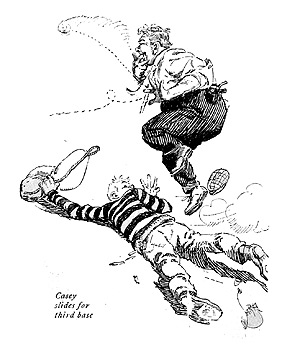

To me the games played by the two great national organizations lack elasticity. I like the games played by the Jeffersonville Stars and the Betzville Arrows much better. The games played by the big league have finer finish, but they lack intensity. Get two teams of husky car drivers and blacksmiths and grocery clerks and set them playing baseball for ten dollars a side, and there is always excitement. The average length of these games is seven innings. When this point is reached, one side or the other is several runs ahead, and the captain of the losing side is ready to contest every decision of the umpire. He stands with his cap in one hand, awaiting his chance, and the chance always comes. The other side is at the bat. He has noticed that his pitcher is weakening. Casey, of the other side, makes a steal from second to third, has to slide for it, and reaches the base about the same second that the ball reaches the third baseman's hand. "Safe on third," says the umpire in his matter-of-fact tone. The captain slams his cap to earth with an air of pained disgust. His fielders lie down where they happen to be; his catcher tears off his mask and makes a run for the umpire, swearing like a madman; his third baseman stands with both feet on base, holding the ball flat against the back of the base runner. The base runner lies flat on the ground with his hand firmly grasping the bag.

The knowing spectators go home at this point, but the amateurs hang around for the riot to begin or the game to go on. Neither ever happens. The umpire -- he knows it is none of his business -- walks over to one side of the field, and engages in conversation with the prettiest girl he can find; the opposing captain makes the usual bluff of anger, and argues with the losing captain. Outsiders butt in, and explain exactly how the man was put out, or exactly how he was safe. The members of the two nines slowly disappear into the saloon on the corner, and reappear dressed to go home. Half an hour later a small group of angry spectators who are still arguing about the decision suddenly discover that they are alone. They grumble a little, and then they also go home, and the game is over.

The Rise and Fall of Skinny Dolon

These games are far from perfect. The scorecards have no place for "errors," for nearly every play is an "error." The teams are apt to be as evenly balanced, as a teeter-totter would be with an elephant on one end and a fly on the other. The first inning begins beautifully, with Skinny Dolan in the box, and Skinny has a wonderful delivery. One after another the batters drop before his curves: He wears a cool, disdainful smile -- and lasts about four innings. In the fifth inning two men hit him for home runs, six for two-baggers, and eight for one-baggers, and three get bases on balls. His appearance in the next inning is away over by the cemetery fence in left field. He gets into the box again in the seventh inning, after Slug Wilson had given six men bases on balls, and everybody makes home runs. That is when his captain begins to watch third base for a close decision.

It is a game of this kind that provides character study, for character comes out boldly in stress, and these games are stress from start to finish. I have seen a quiet little Sunday afternoon game in which every man, on either side told every man on his own and the other side just what he thought of his character. One captain began by telling his pitcher what he thought of him, and ordered him off the field, and the pitcher remarked that if he had a catcher who knew how to catch a ball once every week or so he would be able to use some speed. This seemed to displease the catcher, and he remarked in no gentle tones about the pitcher's general ability and the shortsightedness of a captain who would have such a man on his nine. This gave pleasure to the opposing nine, and they showed it by appropriately guying remarks, and were taken to task by the nine men of the other side. The two hundred spectators who had gathered to see the ball game then told both nines what they thought of them, and were given to understand that not a man on either nine cared a faded fig for --. An hour later the umpire went home, or in the direction of home, but the two captains were still discharging their men. I have seen one stout catcher discharged eight times in one seven inning game, during which period he resigned four times of his own accord.

Capital Punishment for Umpires is Going Out

But it is the umpire of these games who has the sinecure. The old custom of going after the umpire with a bat is about played out. In professional games he is so enclosed in rules and regulations that he is safer than a knight in full armor, and in non-professional and semi-professional games he is only permitted on the diamond as a sort of decoration. So long as the decisions apply only to points that a two-year-old child could decide he is allowed to have the fun of making the decision; but the moment a decision is close he is forgotten, and the two captains double up their fists and talk it out. It doesn't matter in the least what the umpire has said. It is all a question of lungs, vocabulary and bluff. If Captain A is three runs ahead, and the decision does not affect his chances of victory greatly, and his pitcher is still strong, he will merely argue for half an hour and then let the other side have the decision, and the meek little umpire will be called back into the diamond and allowed to fritter away his time calling balls. But if the game is close, and Captain A's, pitcher has begun to weaken, then justice must hold her sway. The rule seems to be, let the umpire make a decision; then let the side decided against make a protest; then the umpire goes to the sideline and talks about the weather while the two nines argue the decision; when they have settled it to suit themselves, someone tells the umpire how it has been settled. If he objects, a new umpire is secured. This method is much more refined than the old way of killing the umpire between the sixth and seventh innings.

Baseball deserves to be our national game. It is not gentle, and we are not a gentle nation. Its best exemplification is by specialists, and as a nation, the specialists are doing our best work in all lines. There is nothing we like so well as to sit around and watch our specialists do their work, and then to get off somewhere and tell each other how much better they might do it, if they would only take our advice. We are hero worshipers, and professional baseball creates just about the right number of heroes to go around. It is not necessary for each man to have the same hero, which soon becomes tiresome. The comic element is introduced by the umpires, who have become a national joke and rank with the mother-in-law witticisms. Baseball is a grand game.

A Safe Game for On-Lookers

As for myself, I would rather go out and see a baseball game than be a baseball player and stand up and let one of those modern pitchers, who throws a ball with the speed of a four-inch gun, cast a wiggling ball at my person, and take a chance on the ball dodging around me before it bored a hole through me. I have been hit by a baseball thrown by a gentle hand, and I know how hard a baseball is. Nor would I care to take to pitching as a serious occupation. To one unacquainted with the game it may seem a safe job to stand up and throw hard balls at the other fellow, but once in awhile a batter hits the ball, and hits it hard, and it makes a bee-line for the pitcher. The pitcher is usually an agile man, but he is seldom agile enough to lie down in time to let the ball pass safely above him, and if he did, his captain would possibly be angry. The ethics of the game require the pitcher to stand right there and let that mile-a-minute ball bore itself into his hands. I did that once, and the palms of my hands still palpitate with fear when I think of it. It was soon after that hot liner that I retired from baseball permanently. Some persons of weak character would never have wished to see another game of ball after such a harrowing experience, but I still love to see the national game, if I can have a seat in the grandstand, with a stout wire netting between me and the scene of slaughter.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 2:40:52am USA Central