|

|

from Success Magazine

Mrs. Casey's Dollar

by Ellis Parker Butler

Mr. Simon Yoder, president of the English Valley Railway Company, stood on the station platform and looked at the company's only passenger coach. He was feeling particularly pleased with himself, for, as president of the West English Cheese Factory, he had just made a contract for the sale of the factory's entire output of cheese, and, as president of the West English Bank, he had bought a couple of mortgage notes that would undoubtedly have to be foreclosed, making about two hundred per cent, for the bank. For a year or more the conductor had wanted the car windows cleaned, but President Yoder was not an extravagant man.

"If somebody wants to look out of those car windows," he would say, "it ain't no use to. It ain't much to see out at. I can't afford window washings when round trips to Kilo is only one dollar. One dollar only pays for ridings; it don't pay for scenerys."

The one dollar did not pay for much but "ridings" on that line. It did not pay for "heatings" in the winter, and it did not pay for speed, or comfort, or cleanliness. If a passenger paid the dollar and conditions were favorable, he was often able to ride to Kilo and back at the speed of an ox team, and only have to get out to help the engineer patch up the engine a half dozen times or so during the round trip of thirty-four miles. It was not a stylish railway, but it was an economical one, and economy is in many ways a beautiful virtue. It is a virtue in which Simon Yoder was a star of the first magnitude. He was so economical that he made Benjamin Franklin's maxims of thrift seem like the reckless gabble of a spendthrift.

Therefore Peter Geis, the conductor, fell off the station platform and skinned the palms of his hands on the cinders when he heard President Yoder's instructions.

"Them windows is too smutty, already, Geis," he said, smoothing his shiny Prince Albert coat over his plump stomach. "Decent railways don't have such smutty windows. Tomorrow get them windows cleaned up good."

Geis looked at his superior to see if he was joking, but Yoder never joked, and his hard jaw was as uncompromisingly firm as ever.

"Yes," said Geis, obediently, "but why now, so soon? Now is it June, already, and peoples opens the windows down. It ain't no use wasting a dollar --"

Yoder ignored the advice.

"Who was cleaning them windows last time, Stein?" he asked. "You get who it was cleaned them last time."

Stein shook his head, sadly.

"She's been dead already six years, yet," he said. "She ain't washing car windows. She's quit already."

Yoder frowned.

"So!" he exclaimed. "So is it she loses a good job, dying like that."

"Mrs. Casey washes. She ain't so expensive," suggested Geis.

Yoder nodded, with dignity.

"Get Mrs. Casey," he said, grandly. "We pay one dollar for the job. Tell her one dollar, Geis. I ain't so loony about that window washings, but I give one dollar. One dollar ain't so little."

He turned to go, and then returned.

"Geis," he said, beckoning to the conductor with his head, "she can begin at six tomorrow morning. At six it ain't so hot yet."

Geis stared open-mouthed at the broad back of Yoder as the president moved with stately tread up the street. It had been so long since a dollar had been spent for improvements to the railway that this sudden expenditure stunned him, and the thoughtfulness for Mrs. Casey's comfort added to his surprise.

"I guess Simon's going loony, already," he said to himself. "He ain't letting loose of so much money if he ain't loony," and then, remembering the revival meetings that were being held, he added, "or mebby Simon's got religion. Some folks' religion makes them spend money. It ain't like Simon."

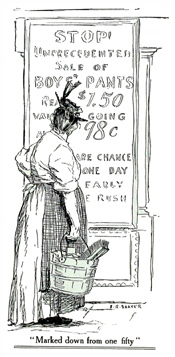

Mrs. Casey was glad to get the job. She was at the car on time next morning, with pail and rags and soap, and went to work. At six thirty the car, preceded by the engine, pulled out from the station on its trip to Kilo, and all the way down and back Mrs. Casey scrubbed and polished, and when the train pulled into West English station the job was done, and she was ready to hurry uptown and collect the dollar, for her son Mike, five years old and freckled like a guinea hen, was lying in his bed at home because Dugan's goat had eaten his pants, and he was due at school, at one o'clock, to speak the "Charge of the Light Brigade" in the grand closing exercises of the year and term, and Edmiston, the general-store man, was having a sale of boys' pants at ninety-eight cents, marked down from one fifty.

As the car stopped she jumped from the step and ran up the street toward the bank, to find President Yoder and collect the dollar.

Edmiston, as she passed, was taking down the special sale sign.

"Aw! Misther Edmiston," she coaxed, "wud ye but lave th' sign be till I run up t' th' bank an' git wan dollar Misther Yoder is owin' t' me, that's th' dear man? I'm wantin' a pair o' thim ninety-eight cint pants fer Mike. He ain't got no pants at all."

Edmiston continued to take down the sign.

"That's all right," he said. "How old is Mike? Five? I'll put aside a pair of five year olds for you."

Mrs. Casey hurried off. She was round and weighty and to hurry made her gasp and groan. When she reached the bank the president was not there. She went to Yoder's house. Mrs. Yoder said he had gone out to the cheese factory. Mrs. Casey panted out to the cheese factory. She found Mr. Yoder sadly picking up pieces of a cheese that had fallen off the scales and broken.

"Will ye give me th' dollar fer th' cle'nin' of th' car, Misther Yoder?" she gasped. "An' quick, fer Mike's in bed, him havin' no pants t' his name, an' 'tis goin' on twelve o'clock this minute, an' school takin' up at wan o'clock."

Mr. Yoder dropped a piece of the cheese, he was so startled. Not in fifty years had any one been so rash as to ask him for money suddenly.

"Ach!" he cried, angrily. "Now see! That piece of cheese ain't hardly good for fish baits! She's gone to nothings, already. People don't ask for money so sudden. That ain't business. I don't like giving my money to spend so quick; that ain't no decent way to treat money."

Mrs. Casey glared at him.

"An' phwat is it t' you, annyhow?" she asked, with equal anger. "'T is me own money. Wud ye hev Mike spakin' th' 'Charge of th' Light Brigade' stark naked, loike wan av thim Feejee haythin? Give me th' dollar, Misther Yoder."

Mr. Yoder bent down and picked up a cheese remnant. He dusted it carefully with his plump hand.

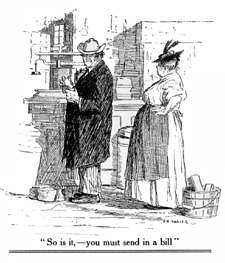

"So!" he said, mildly. "I ain't paying out for the railroad company, Missus Casey. I ain't the railroad company, already. I ain't but president. I ain't so much, yet. I ain't got all the say. Them directors, they got a say, too. They pass on bills. You must send in a bill, yet. So is it -- you must send in a bill for that dollar." He went on dusting the cheese.

Mrs. Casey put her hands on her hips and swore with her eyes. Oaths snapped in her red hair, and profanity glowed on her brow.

"A bill!" she cried. "A bill! An' ivry blissid moment Edmiston's raisin' up th' price av pants from ninety-eight cints t' wan fifty, beyond th' reach av me, an' Mike weepin" his eyes out wid you a sthandin' here wipin' th' mud off a chunk av chaze not fit for a pig t' ate an' shoutin' at th' top av yer voice fer me t' mek out a bill! Oh, thank ye, Misther Prisidint Yoder!" lowering her voice to her most bitingly sarcastic tone. "An' do ye think, Misther Prisidint Yoder, I carry me pen an' ink an' me day book an' ledger an' me journal an' writin' desk an' a blotty paper whiniver I go washin' windys? 'T is in haste I am, Misther Prisidint Yoder, if ye plaze, fer Mike's pants was intirely et up by Dugan's goat, includin' the suspinders --"

Mr. Yoder calmly raised another piece of cheese from the floor and began picking dust specks from it.

"It does no good to talk so much, already," he said. "Talk is nothings; hurry up is nothings; pants is nothings! Nothings is nothings! I was not eating up Mike's pants, yet. Pants makes no differences with railroad companies. Pants has not to do with bills. So it must be, always -- a bill! Such is the system -- a bill! Such is the business -- a bill! Always it is -- a bill!"

Mrs. Casey folded her arms and eyed him sarcastically.

"Th' prisidint av th' railyroad," she said, slowly. "An' th' prisidint av th' bank! An' th' prisidint av th' chazc fact'ry! requestin' a leddy t' mek out a bill fer th' treminjous sum av wan dollar! Much oblige t' ye, sor! A bill I will mek, but let me say wan worrud -- There be negroes an' they be black; an' there be injuns an' they be dhirty annimals; an' there be Frinch, an' Rooshuns, an' Eyetalians, an' all th' races av min thet kem out av Noah's ark two by two, an' some of thim be dang mean, but whin th' divil created th' combination av a railyroad prisidint an' a Pennsylvany Dootchman he bruck the record! Good day t' ye!"

The air of her departure was magnificent. She had the spiritual presence of rustling silks and glittering diamonds, but her high-uptilted nose was a plain, mad pug.

President Yoder looked at her unmoved, and then turned to the cheese.

"Too bad!" he said, with real sorrow. "Man can't hardly sell such busted cheese for nothings."

Mrs. Casey was as quick to recover her cheerfulness as she was to get in a temper, and in ten minutes she was herself again. She let Mike sit up in a cane rocker with a blue gingham apron tied around his waist, and she wrote her bill with a stubby pencil on a sheet of blue-lined note paper that Mike had once brought home from school to use in writing a specimen letter describing an imaginary vacation, but had spoiled.

The bill when completed read -- thanks to Mike's essay at a letter -- as follows:

"Dear Teacher, i had a verry nice vacat-- (big blot) ion. i plade with (big blot) Mr Yoder oes me one dolar for washin car windys Mary Casey."

She hurried with it to the office of the railway company on the second floor of the bank building. She climbed the iron outside stairs, and tried the door. It was closed and locked, and she sat herself down on the top step and waited. At a quarter of one she heard the school bell ring, and she wept; at one minute of one she heard the "last" bell ring, and she dried her eyes. At one there was the single stroke of the "tardy" bell, and she set her teeth and clenched her fists.

It was five minutes after one when President Yoder ascended the stairs. Mrs. Casey stood majestically aside to let him unlock the door, drawing her skirt carefully away from him. This was intended to sting him to the heart with her contempt.

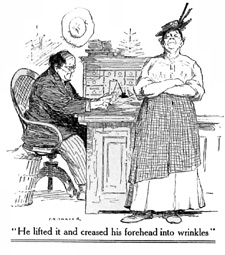

She followed him in, and stood beside his desk while he took off his hat and seated himself, and then, with the air of injured innocence playing a trump, she laid the bill on the desk before him, and folded her arms.

Mr. Yoder put his spectacles on his nose carefully and picked up the sheet of paper. He read it; read it again: frowned and looked a question at Mrs. Casey, who was standing glaring down at him.

"What is it?" he asked, puzzled. "I don't know what is it?"

"'Tis th' bill!" said Mrs. Casey.

"So?" he asked, drawing the word out long and thin. "The bill? So-o! It is the bill?"

He lifted it and creased his forehead into wrinkles.

"'Dear teacher,'" he read, slowly spelling out the words, "'I had a very nice vacation.' -- What is it, Missus Casey? It is no bills."

Mrs. Casey's nose trembled like an offended rabbit's.

"Rade on!" she said, coldly.

Mr. Yoder took up the paper again.

"'I--I--p-l-a-d-e, played with --'"

Mrs. Casey leaned forward.

"Th' bill commences t' begin there," she hissed. There was but one sibilant in the sentence, but she made it hiss for all the six words.

"'Misther Yoder,'" he read, '"o-e-s, owes, me, one, dollar, for, wash, in, windys, Mary, Casey.'"

"An' so ye do," said Mrs. Casey.

"No," said Mr. Yoder, "I owe nothings. The railway company owes -- mebby. Make a new bills -- English Valley Railway Company, so!"

He handed her a sheet of paper. It was a handbill, printed on one side with a sale notice, with a picture of a fat cow. Mr. Yoder did not waste things. Mrs. Casey took the paper and leaned over the desk. She put the heel of one foot on the ankle of the other and began to write.

"And, say!" said Mr. Yoder. "Don't put in such about 'Dear teachers' and all. I ain't understanding those 'Dear teachers,' anyhow. Such makes nothings any better. Leave it out. So much writings uses up my pencils too much and ain't no use."

He took the bill when Mrs. Casey had completed it and looked at it approvingly. Then he folded it up and put it in the pigeonhole marked "Bills." The pigeonhole was so full he had to squeeze its contents down to make room for the newcomer. Then he smiled.

"Good!" he said, with satisfaction. "So is it all right once."

Mrs. Casey did not smile at this pleasantry. "I am waitin' fer th' dollar," she said, coldly.

Mr. Yoder shook his head.

"It is not so bills is paid, yet," he explained. "Railroads run by systems. Without systems could there be no railroads; everything busts up, like cheeses. So is there systems, already. So is there time tables, and rates, and rebates, and all systems. Everywhere is systems. For everythings is some systems. And for bills is systems, too."

"'T was not fer systems I kem here, Misther Yoder," said Mrs. Casey, "but fer wan dollar t' buy pants fer Mike, him bein' half naked wid Dugan's goat eatin' th' pants off him, an' Edmiston holdin' out a pair fer ninety-eight cints while I git th' dollar. I give not wan dang fer yer systems, Misther Yoder! If I hed twinty systems Mike cud not wear thim on th' bae legs av him."

"Business is business," said Mr. Yoder, slowly. "And, in railroads, systems is business. Such is the systems -- You give me a bill,yes; here is the bill filed, yes. Comes the first of the month, and so is the bill sent to Stein, the conductor, for ' O. K.,' already, yes. Then comes the bill for my ' O. K.,' yes. Then, next month is the board of directors meeting and comes the bill to vote, yes. When the directors vote 'yes,' goes the bill by the auditor, yes. Next makes out the auditor a voucher, yes. Goes the voucher to the cashier, yes. And then," he said, bringing the flat of his hand impressively down on his desk, "if is so much money by the treasury, is the bill paid! So is the system. Nothing changes such a systems. Always is it the same. Not for nothings is the systems changed. Not for nobody at all. Always, always, always is the system!"

Mrs. Casey's face had been growing longer and longer. Hope departed and bewilderment came.

"An' whin -- whin, sor, kin I be expectin' t' receive th' arrival av th' dollar, Misther Yoder?" she faltered.

Mr. Yoder raised his eyebrows and shoulders. He was kind, even cheerful, but indefinite.

"Now is but June," he said. "June! Hah! June! Say -- say Detcember. Not after Detcember. Such systems is not fast, no; but sure, yes."

Mrs. Casey turned and walked straight to the door. She went out. Mr. Yoder picked up the old bill from where it had fallen on the floor and, tearing off the strip at the bottom on which Mrs. Casey had not written, put the unused part carefully away for future use. A hundredth of a penny saved is a hundredth of a penny earned. Mrs. Casey put her head in at the door.

"Daycimber!" she cried. "Daycimber!" "'Twill be plisint fer Mike wid no pants in Daycimber! If the lad catches pneumonia in his bare legs by it I'll hev th' law on yer illegant system! Remimber that, Misther Prisidint Yoder!"

She went down the steps, and at the bottom she glanced sideways toward Edmiston's store, across the street, and hurried on, for on his ledger Edmiston had an old, old account against Mary Casey, and across it, in violet ink that pretended to be black, was written "N. G." When she had money in hand Mrs. Casey did not bear Edmiston ill will because she owed him that outlawed account. She was willing to let bygones be bygones and forget the old account; but when she had no money the old account accused her, and she felt guilty, and always avoided him as much as she could.

"Hey!" called Edmiston, "Hey, Mrs. Casey!"

Her impulse was to hurry on, but she could not pretend ignorance of that voice. It was loud enough to call home a deaf cow from the next county. She hesitated, and crossed the street, formulating her excuse as she went.

"Th' ould cheese-rind av a Yoder," she began, but Edmiston interrupted her with a laugh.

"Wouldn't pay? I thought so. He has to hug a dollar for a month or two before he kisses it good-by. I was thinking I ought to have this store cleaned up -- shelves scrubbed, walls washed -- wonder if you would do it for me?"

"Wud I do it?" cried Mrs. Casey. "Ah, you're th' swate gintleman as iver was, Misther Edmiston! Lave me but git me pail from me shanty --"

"Not today," said Edmiston; "nor tomorrow, that's market day. Say Monday. And here's the boy's pants you spoke for. They can come out of the --"

Mrs. Casey did not wait to hear.

"Hivin' bliss ye, Misther Edmiston!" she cried, grasping his hand. "If there be room fer another saint in hivin, wid them so crowded already, sure 't will be Saint Edmiston av West English! 'T is th' patron saint av widdys an' orphans ye be sellin' wan fifty pants fer ninety-eight cints, an' takin' thim out in worruk, an' nivir sayin' th' worrud 'system,' which was invinted be th' divil t' oppress th' laborin' man. Thank ye, sor, an' much oblige t' ye, an' if ye wor th' divil himself I wud say th' same."

Mike's clothing in summer consisted of two items: I., shirt, and II., pants. The quickest he had ever dressed was one day when he was swimming when he should have been in school, and saw his mother coming over the hill with a barrel stave in her hand; but he dressed quicker when Mrs. Casey got home with the new pants, for there were two of them, Mrs. Casey and Mike. He was buttoning the top button of his shirt as he took his seat in the schoolroom, "tardy" but "present," and it did not matter, for there was no "next day" to bring retribution.

The long vacation passed, and the autumn months, and the first of December came, but no dollar came to Mrs. Casey from the English Valley Railway Company. On the second she went up to collect the dollar.

"We don't owe nothings," said Mr. Yoder, calmly. "All is settled up, already."

Mrs. Casey wrapped her shawl around her and stood like a statue of Ireland defying the Dutch. She was mad at the Dutch, but she had expected to be mad, and she was glad to be able to be. It was almost worth a dollar.

"Such a bill for one dollar, it was passed 'O. K.' by the systems," said Mr. Yoder. "Stein makes his 'O. K.' on that bill. I make my 'O. K.' on that bill. The board of directors they vote 'yes' and 'O. K.' that bill. The auditor makes a voucher for that bill. All is done as the system says, already. Then comes the voucher by the cashier. Such is the beauty of a systems!' Shall I pay?' says the cashier. 'First look does Mrs. Casey owe somethings,' says the systems. 'When she don't owe somethings, then pay.'"

He paused to let the wonder of the system work into her soul, but her soul was so full of anger there was no room for wonder.

"So!" said Yoder. "He looks. He finds on such ledgers a bill against Mrs. Casey for one dollar. So is all squared up, already. The company owes nothings; Mrs. Casey owes nothings. All is even."

"A bill agin Missus Casey fer wan dollar!" cried Mrs. Casey. "An" fer phwat, may I kindly ask, does Missus Casey owe th' railroad, I dunno!"

"For riding on the cars," said Mr. Yoder, blandly. "Such costs is fer round trips to Kilo. Nobody rides for nothings, yet. One dollar, round trip to Kilo; so everybody pays. And such a round trips you took when cleaning the car windows, already. One way is sixty cents, but I ain't so mean. I ain't charging one twenty. You had a right to buy a round-trip ticket, but I ain't so awful mean, I say let it be for a round trip, anyway. Just one dollar."

Mrs. Casey did not stop to argue. She went down the stairs and across the street and up another flight to the court of the justice of the peace. The case came up promptly, for it was not a busy time.

"Now, when did you clean the windows?" asked the justice, when the case was called.

"'Twas awn th' tinth av June," said Mrs. Casey, positively.

The justice of the peace looked at her sternly.

"Be careful! "he cautioned her. "Be carefull How -- how, Mrs. Casey, do you fix that date in your mind? How can you be so sure of the date of a trifling event that occurred so long ago?"

"An' cud I iver fergit ut?" she asked, angrily. "An'wasn't it Mike's birthday? An' him in bed th' day on account av Dugan's goat havin' et his pants, which was hangin' on th' line, me havin' washed th' day before because th' nixt day was th' last av school, an' Mike goin' t' spake th' 'Charge av th' Light Brigade', an' who iver heard av spakin' th' 'Charge av th' Light Brigade' wid no pants on? Mebby some does, yer honor, but no Casey does, or will, an' shame t' ye t' think it, yer honor. A Casey's as good as th' nixt wan."

The justice of the peace rubbed his whiskers thoughtfully and frowned at Mrs. Casey.

"That sounds like contempt of court," he said. "At least, it is almost contempt of court. You talk so fast I can't tell whether it is or not. If it was, I'd fine you. Next time speak slower."

The defense had a lawyer. He was old Sim Mobray.

"Judge," he said, trembling on his legs, but with the noble frown he had cultivated for fifty years, "this woman has no case. We are prepared to prove, first, she never washed the car windows for the English Valley Railroad; second, that she did such a poor job that she is not entitled to pay; and third, that the railroad has an equal counter-claim against her. I -- I think, Judge, you should advise this woman to go home and attend to her daily round of household duties. What is nobler, your honor, than to see the noble women of our glorious land attending to their household duties? And -- now, mark me! -- what is less womanly, more degrading than to see woman, the noblest and fairest of God's creatures, meddling with the law and seeking to pervert its grand institutions to the base purpose of wringing an unearned sum from the defenseless and -- and oppressed English Valley Railway Company, duly incorporated under the laws of the state of Iowa?"

"Oh, pshaw!" exclaimed the justice, "she did the work. Everybody in town talked about it. You know that."

"Our counter-claim," said Sim Mobray, "is that she rode from West English to Kilo and back, the fare for which trip is one dollar."

"An' did I want t' go?" asked Mrs. Casey, bitterly. "Wud anny one want t' tour th' land in th' ould pig sty av a car that did not hev t'? 'T was thim dragged me away, yer honor, without sayin', 'by yer leave, ma'am.'"

The justice nodded.

"Sim," he said, "Yoder'd better pay up this dollar. You ain't got no case at all. As I understand the law it's dead agin you. First, this woman was an employee and she was entitled to the ride. Second, if you charge her for the riding, she can charge you back with mileage for the same amount. And third, if you get sassy about it, she can sue you for abduction for carrying her, too, when she didn't want to go, and, I tell you, abducting a widow ain't no joke. I never knowed anybody to abduct a widow yet that wasn't sorry for it. I don't know the law on it, but I guess it's pretty stiff. I guess I'll just grant judgment for one dollar and interest agin the railroad, and tax it for the costs."

Mrs. Casey waited expectantly for the dollar and interest. The light of triumph was in her eyes, but Sim Mobray knew his client. He gave formal notice that the case would be carried to a higher court, but, a week later, when the sheriff levied on the rolling stock of the English Valley Railway Company, Mr. Yoder, assisted by the remarks of the people, ordered the cashier to pay Mrs. Casey one dollar and five cents.

"Wan dollar!" said Mrs. Casey, when the round silver disk was laid in her hand. "Wan dollar! An' there be th' dint in it av Prisidint Yoder's fingers from holdin' onto it so harrud! An' t' think Prisidint George Washin'ton wance t'rew a dollar acrost th' Pat-o-mack River fer nawthin' but th' fun av' throwin'! Shure, there be prisidints an' prisidints! An' foive cints intrist!"

She shook her head over the unfathomable ways of capital and corporations.

"Foive cints! Well, annyhow, there be oil trusts an' no wan kin down thim; an' there be railyroad trusts an' no wan kin do annything to thim; an' there be beef trusts an' no wan kin hurrut their feelin's; an' there be systems av foinance in Wall Street an' no wan kin mek thim wink wan eye, but not wan av thim all knows th' knowledge av keepin' toight hold av a cint aquil t' Prisidint Yoder, av West English, and a Casey got wan dollar an' foive cints out av him! Wan hunderd an' foive cints! Shure, 'twill take wan hunderd an' foive years off th' ind av his loife!"

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 3:11:55am USA Central