from Success Magazine

On Jury Duty

by Ellis Parker Butler

|

|

Serving on a jury, like the exercise of suffrage, is one of the great American duties. It is one of the few things a man can do and his wife cannot, and for that reason it is one of the most prized prerogatives of the male. It is a pleasant sight to see the thousands of clear-browed American men clamoring around the jury commissioner very morning, begging to be allowed to serve on a jury. It is a puzzling thing that the ladies who are whooping so strenuously for the ballot have overlooked jury duty. Here is a prerogative of the male that they can grab, and not a male will utter a peep. Any lady wanting my jury prerogative is welcome to it and may have it by asking for it on a return post card. If someone would just stand up and tell the "Votes For Women" ladies that they will be granted, with gladness, the right to vote early and often, but it must be understood that jury duty goes with it, the last suffragette would utter a dismal squawk and go back to the culinary department.

The jury system is an arrangement by which the blame of deciding a law case is spread among twelve men, so that they may make the verdict as idiotic as possible without anyone in particular being to blame. In choosing a jury a large number of men are drawn into the courthouse with a rake called a subpoena. When all of these men are gathered together in the courtroom, the judge turns to the clerk of the court and remarks that the courtroom smells worse than a tannery and bids the court officer to open several windows. This collection of embryo jurors is called a panel, this being more delicate than to call them out and out blockheads, while still suggesting that they are wooden. The judge then looks over this collection of galley slaves with a sad, discouraged look, heaves a sigh, and tells the clerk to let-her-go-Gallagher.

Immediately nine-tenths of the panel stand up in line and prepare to explain to the judge why they cannot possibly serve as jurors just then. The excuses available are as follows:

Sore toe.

Twins.

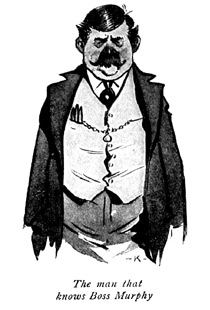

Acquaintance with Boss Murphy.

Mother-in-law at the house.

Deafness.

Epizootic.

Fits.

Cold feet.

Spring fever.

The judge listens to those excuses with an air of considering them carefully, and then tells the man that knows Boss Murphy that he may go. The others file back into the panel with sheepish grins, and the law takes its course.

Twelve victims are asked to step into the jury box. One is dismissed because he can't chew tobacco without getting too much of it on his beard; another is let go because his nose is like Aaron's. Other jurors are put in to fill their places; the lawyers ask obnoxious questions, and at last the trial begins. Eight of the jurors immediately turn their eyes on the pretty girl on the seat at the left, third row back, and try to look handsome. The foreman assumes a studious appearance and places his fingers on his forehead. One juryman begins chewing the ends of his nails. The twelfth juror is an intelligent, fine-looking, well built American citizen. I need not say who he is. In every case where I have served on a jury the jury has been composed of one intelligent citizen and eleven semi-idiotic and unbelievably stubborn donkeys.

Let us suppose the case is that of a man. The man is said to have stolen a cow. He is said to have gone into the pasture and removed the cow to his own barn. The other man wants the cow back. You see, the case is very simple. If the lawyers had sense enough to leave it that way even the eleven sodden jackasses on the jury could see through it, but after one lawyer has had his fun with the witness, the other lawyer -- the lawyer of the cow stealer -- wants to show that he is earning his pay. The one intelligent man on the jury has heard enough. He has made up his mind just how that matter ought to be settled, and he is annoyed at the childishness of going any further with such a clear case. He resents it. He turns away from the lawyer and looks at the pretty girl. She is the daughter of the man whose cow was so unjustly stolen.

But the lawyers are not willing to leave the case that way. They keep introducing more and more evidence, or what they are pleased to call evidence. It seems that the man that stole the cow claims he did not steal the cow. He claims it was his cow, and that it was only in the other man's pasture to eat the succulent grass. He claims he put the cow in that pasture every morning and took it out every night, and all that he ever did was to agree to pay the man so much a month for the use of the pasture, and the reason the other man claimed the cow was his cow was because the man that stole the cow had never paid for the use of the pasture. And the reason he had not paid for the use of the pasture was because he had loaned the man that owned the pasture a horse. Then the man that claimed he owned the cow, and that it was stolen from him, put on an expert witness to prove the value of the cow and the value of the use of the pasturage, and to prove that the value of the use of the pasturage had amounted to just the value of the cow, and that in claiming to own the cow he was perfectly right. Or else the other man did this. One of them did, anyway. Then one of them claimed that the horse had died, and proved the value of the horse, and that it did, or did not, just equal the value of the cow and of the use of the pasturage. The other man proved that he had bought the horse outright, and had paid for it, so the horse had nothing whatever to do with the cow, but the other man proved that the horse was paid for with a check and that the bank had refused the check and assessed him four dollars and sixteen cents protest charges on the check. Then the other man, or the same one -- one of the two men, at least -- proved that when the cow was stolen it was hurried to the other man's barn so rapidly that it was overheated, and damaged, and that he ought to have damages for that. Then the other man introduced a witness to prove that the man that claimed he owned the cow had never owned it at all, but had bought it with a note and had let the note go to protest, and that the man that held the note was the real owner of the cow, and he, if any one, should have the damages or be put in jail for stealing the cow. Then witnesses were put on the stand to prove an alibi for the man that stole the cow, and other witnesses were put on to prove an alibi for the cow. Then each side put on witnesses to prove that neither of the cow owners nor any witness on either side was worthy of the slightest belief, but that they were all perjurers and chicken thieves, or worse.

This ended the testimony and the two lawyers made their pleas to the jury. One lawyer talked for an hour, but the other talked for two hours and six minutes, so the first had the sentiment of the jury strongly in his favor. The judge then charged the jury and advised them that nothing the two lawyers said was worthy of the slightest credence, and that it should not be considered for an instant. He then explained the case in his own way, and told the jurors they had nothing whatever to do with the law in the case. All they had to do was to consider the evidence and that this was such a simple case they should have no trouble in deciding it. Finally he told them what kind of a verdict they should bring in. If what the cow stealer said was true, they should bring in a verdict of manslaughter in the second degree, arson or suicide, but if they decided that what the other man said was true beyond a reasonable doubt, they could bring in a verdict for punitive damages, using the United States mails for fraudulent purposes, or assault and battery. He then sent the jury into confinement in the jury room, first calling the court officer aside and warning him to keep an eye on us, as we looked like suspicious characters. The jury filed out, keeping one eye on the pretty girl. I have gone into the details of this case so that the reader may be able to understand the arguments that took place in the jury room. Otherwise all would be blank to him.

Upon being locked in the jury room the fat German -- juryman No. 7 -- took the easiest chair and immediately went to sleep. Occasionally, during the discussion that followed, we awakened him to vote; but generally we voted for him as it saved trouble. He was a most inconsiderate juror and every time he was asked to vote, he required a statement of the case, as we had argued it out up to that time and in explaining it to him the jurors got so mixed that those who had argued on one side found themselves giving arguments for the other side, and the voting had to be postponed until they could remember which side they were on before they began explaining to juror No. 7.

As soon as we entered the room, and while juror No. 7 was falling asleep, the foreman pulled a chair up to the table and began tearing a sheet of paper into slips.

"Now, gentlemen," he said, "I suppose we want to proceed in an orderly manner, and as I understand it, the foreman should be the chairman. I will appoint jurymen 5 and 8 as tellers. I propose that the first thing we do shall be to take a vote. It may be that we are all of one way of thinking, and if so a vote will show it, and there will be no need of wasting time, because I have about three hundred chickens at home and I ought to get home in time to feed them."

"I have a lot of chickens, too," said juror No. 11, "but I shouldn't let them interfere with my duty as a juror. No sir! I believe that when a juror has sworn to do his duty as a juror, and has sworn to do it, it is his duty to do it if he has sworn to, and I am surprised to hear the foreman speaking in this way. I won't say anything about jurymen being bribed; all I say is that I say if a juryman has sworn --"

"All right," said the foreman angrily, throwing down the slips of paper, "maybe you know how to do my duty better than I do. What have you got to suggest?"

"I have got to suggest," said juryman No. 11, "that what we ought to do as sworn jurors in this case is to take a vote without thinking of chickens. It doesn't matter whether chickens are fed or not fed -- we've sworn to settle this case."

Just here juror No. 4 arose, and poked his peaked little face with its spectacle-straddled nose close to the foreman's face.

"Mr. Foreman," he squeaked, "I am in favor of voting too, but before I vote I want to ask a question. What is it about the chickens? I went to sleep in the jury box, and I missed all that about the chickens. Some men might go ahead and vote on a case like this without knowing all about it, but I am from New England and I've got a conscience. I can't vote on a thing I don't know all about. Whose were the chickens?"

"Say," said juror No. 11, "if I swore to do my duty as a juror and went to sleep I would shut up. That's what I'd do. The chickens belong to me and the foreman here. Now, sit down."

The conscientious juror bent his knees as if to sit down.

"I shouldn't think that anyone that had chickens in the case should be on the jury in the case," he said, and then he sat down.

"Them chickens ain't in the case," said No. 11, spitefully. "I'll tell No. 4 all about them chickens --"

"Oh, shut up, and vote!" said juror No. 8! "I don't want to stay here all night listening to you fellers gas. Get a move on and vote."

The foreman handed the slips of paper to the tellers who distributed them, and when they were inscribed, gathered them in a hat and poured them upon the table. When they had listed the votes they reported the result to be as follows:

Conviction .............. 5

$5,000 .................. 1

Abduction ............... 2

Not Guilty .............. 1

Blank ................... 1

Suicide ................. 1

$8.45 ................... 1

When the foreman heard the result he was greatly pleased, and said that it looked as if a verdict would be reached without much trouble. Five, he said, were already for conviction, and if the other seven came over it would be unanimous. He asked all who were in favor of conviction to stand up. Three stood up. The foreman looked discouraged, but he said that as the convicts were still the most numerous he would proceed in an orderly manner and ask the three convicts to explain why they favored conviction. At this juror No. 11, said he voted to see the cow stealer convicted because he thought it was his duty as a sworn juror to abide by the evidence. Juror No. 6 arose and said he was in favor of conviction too, but he was in favor of convicting the other man, because it was plain to him that a man with a wife and six children should not vote to harm a man with a wife and five children. He said he knew how it was to have a wife and six children because he had a wife and six children himself, and the man with a wife and five children might have a wife and six children at any time. Then he sat down. Juror No. 2 said he was in favor of conviction because he was always in favor of it; crime was growing right along and whenever a jury could convict anything or anybody it ought to do it, but he didn't care which man was convicted, or what for. He said all he cared for was to see somebody convicted and he would stick to that if he had to stay there all night. He said he was an honest man, but the country was getting too full of thieves.

"You talk like an anarchist," said juror No. 4. "I voted 'Not Guilty' and I am not ashamed to say so. I know plenty of cases where innocent men have been sent to jail by juries, and I'll never stand for anything like that. No, sir! I voted 'Not Guilty,' and I'll vote the same if I stay here a week."

"Well, Mr. Foreman," said juror No. 3, arising, "I voted a blank and I had a reason. I have listened to these gentlemen, and their arguments are fine. They are all right and they convinced me. But I've been on juries before, and I know you will never get a verdict that way. You've got to compromise. That's why I voted a blank. I'm willing to go the way the majority goes, every time, and what I say is that we take these twelve ballots and figure them out and split the difference. Now, here is one for $5,000 and one for $8.45, and the compromise would be $2,504.22 1/2. Then there are five for conviction, and one for not guilty. That would leave four for conviction, by subtracting one from five. Then there is one for suicide and we are willing to admit, I guess, that the horse committed suicide. There are two for abduction and we can split that up easy. Each of those farmers claimed that the other abducted the cow, and if one abducted it, and the other abducted it, that would be two for abduction and the cow would be just where it was, and those two abduction votes would cancel each other. So it would stand like this: 'We the jury, find that the horse committed suicide and that it should be fined $2,504.22 1/2.'"

After that the jurymen talked about the tariff and told funny stories until they had smoked all the cigars in the room, for the conscientious New Englander would not agree to the verdict. The other jurors talked to him one at a time, and two at a time and eleven at a time, but it was no use -- his conscience would not allow him to accept a compromise verdict. He still had a cigar left.

"Well now," said the foreman, after awhile, "I'll tell you what we will do. No. 4 is the only man standing out. We are eleven to one, but we are all fair-minded men, and we are willing to recognize conscientious scruples. I think the best thing to do would be to try another vote. And in the first place, are we all agreed that the horse committed suicide?"

"We are agreed."

"Then," said the foreman, "the only thing to vote on is the amount of the fine."

The tellers again passed the slips, and when they were gathered up and scheduled the vote proved thus:

$2,504.22 1/2 ........... 11

$2,504.22 ............... 1

"Now, then, No. 4," said the foreman, "we are pretty close together. I'll tell you what we will do. We will split the difference. Make it $2,504.22 1/4"

"All, right," said No. 4, after he had felt in his pocket for another cigar, and had found none.

The foreman then set to work to put the verdict in proper language. He wrote for several minutes, putting in and erasing, while the other jurors stood up and gathered their hats and coats together.

"How's this?" he said at length. "We the jury, find that the horse committed suicide and is entitled to pay a fine of $2,504.22 1/4."

"Come on, that's all right," said No. 8.

"Wait a minute," said No. 6. "That's all right, but how can a dead horse pay anything? We should --"

"Oh, come on, come on!" said juror No. 5. "We don't want to stay here forever. What do we care?"

"Now, I won't go into that courtroom making a dead horse pay money. The judge would send us back," said juror No. 6.

"Well, fix it up then," said two or three jurors. "Hurry on. The judge will be gone and we'll be locked up here for the night."

"How's this, then?" asked juror No. 6. "We, the jury, find that the horse committed suicide, and that the owner shall pay damages to the amount of $2,504.22 1/4 to the --. Shall I put it plaintiff or defendant?"

"What do we care? Hurry up, that's all we want." "Well, say," said No. 6, "which was the dad of that pretty girl?"

"The man that stole the cow was her father. He was the defendant. Hurry up, can't you?"

"Just wait until I get this horse in right --"

"Oh, hurry up! Leave the horse out. Come along."

And that is how we happened to turn in a verdict finding for the defendant in the sum of $2,504.22 1/4.