from Leslie's Monthly

The Great Park Strike

by Ellis Parker Butler

If you know the park I have in mind you will remember the rows and rows of baby cabs and go-carts that line the walks, and the dozens of nurses and mothers that sit on the benches. It is a great place for us babies; plenty of sun and fresh air and a sky so high that cries do not echo against it, and a finer lot of well-kept infants is not to be found in the city of New York, if I do say it myself.

You may remember me, too, if you have ever visited our park. I am the baby in the English perambulator with the blue collapsible top. Many people -- my parents in particular -- have mentioned my intelligent expression and have commented favorably on my manner of sucking my thumb. But I do not pride myself on these points, for my parents are quite intelligent for grown-ups, and my grandmother has often said that my father sucked his thumb in much the same manner, so I presume these are hereditary traits. But I will say that I am the only baby in our park that has had its picture in the magazines. And I can honestly recommend the brand of infant food that was mentioned in connection with my portrait. It undoubtedly makes handsome, intelligent babies.

I am not of a suspicious nature. I believe in considering everything good until it proves itself bad. I am ready at any time to eat anything that my hands can convey to my mouth. I remember distinctly trying to eat the hot end of a cigar, but I shall not do so again. When I have proved a thing bad that settles it. It is the same with people. I like every newcomer until he or she turns out to be disagreeable and tries to kiss me or rub me against his day-old beard or "tootsy-woots" me under the chin. But the minute I saw the Scientific Mother I knew there was trouble ahead.

She came into our park without a baby -- I learned later that she was a spinster -- and she passed along the walks handing out little sheets of paper to the mothers. Every time she handed out a paper, she chucked a baby under the chin and grinned and said: "What a sweet child." She was a long, lank woman with gold-rimmed eyeglasses that made red marks on her nose. When she chucked me I very properly broke into what we term the "disagreeable stranger cry," which is an agreed danger call of the Babies Protective Union. I noticed that the cry had the intended effect, for it was quickly passed along the line.

My suspicions were well founded. The woman was a Scientific Mother of the most virulent type, and her object was to deliver a course of lectures on Scientific Motherhood. Scientific Motherhood is a state of mind into which otherwise kind parents get, that causes them to offer cruel and malicious affronts to their helpless offspring. Men and aunts can be Scientific Mothers, but grandmothers can't.

It is rather a new thing, like automobiles and airships, and consists in making a baby do whatever it doesn't want to do, and in not letting it do whatever it does want to do. Anyone who can think of a new thing that a baby doesn't like, and can make a baby do it can get a diploma as a Professional Scientific Mother. We soon learned that the thin woman was the Head Professional Scientific Mother of the United States and that she had a great influence on weak-minded parents, which are most parents.

"Uncomfortable clothes are healthful."

"When a baby is wide-awake it needs sleep."

"Learn to say, 'Baby mustn't.'"

All these things were originated especially to render baby life less placid. We had heard of them from babies from other parks who had visited us from time to time, and it was this advance knowledge that had induced us to form The Babies' Protective Union No. 1.

In forming the Union we had to proceed most carefully lest our parents and nurses fathom our design, and it was rather hard to hold our meetings when we were scattered along a mile or more of park walks but the plan was finally perfected, and as I had the strongest voice I was made Baby in Chief.

I smile when I think how unsuspicious our parents were. My mother often said "How sweet" when I gave Dot McNulty or some other baby of the Unit what we call the Kiss of Brotherhood, and all our newly invented sign manuals were looked upon as new baby tricks. I remember the day when I shook my rattle for the first time. My mother was delighted and had no idea I was merely signaling to Toots Williams the information that our regular meeting days had been changed from the first and third Tuesdays of each month to the second and fourth.

In fact our means of communication were so limited that we were forced to give a secret meaning to every motion of the hand, contortion of the face and tone of the voice, and as rapidly as we learned new words we incorporated them in our code. It is not for me to make public our manual, but it is odd to see the pleasure of a mother when a member of the Union puts his arm lovingly around her neck and kisses her, when, instead of a love caress, the action is a signal to some other member of the Union telling him that the woman embraced is a spanker.

Quite unsuspicious of the existence of our Union, the majority of the mothers of our park joined the Scientific Motherhood Guild and we soon began to feel the dire effects. The first act of tyranny was to put us all on a time diet -- one feed every two and one-half hours. The crisis came when Dotty McNulty brought her grievance before the Union. She had had a meal due at eight, and the clock stopped. She waited twenty minutes longer and then gave the Brother in Distress yell, followed by the Brother Still in Distress cries, but her unfeeling mother only looked at the clock and continued sewing. It was after nine before it was noticed that the clock had stopped and Dotty was then on the verge of starvation.

The Union had been restless for some days before and Dotty's story decided us. If our food was to depend on clocks we were in mortal danger. If a clock became permanently disabled, one would evidently be forced to starve to death. We voted unanimously to strike for our rights.

In our park the day of the vote is still spoken of by our mothers as the day of the Nursing Bottles. This came about by accident. In putting the question to the assembled babies I said: "All in favor of striking will make this sign," and I then made a downward and outward motion with my hand. I had not noticed that I held my nursing bottle. It slipped from my grasp and crashed on the cement walk. "Without hesitation all the members of the Union seized their nursing bottles and dashed them to the ground. The sound of crashing glass ran through the park like the shots of a regiment firing at random. One or two members who were taking nourishment at the time hesitated a moment, but, taking a last swallow, they tore the bottles from their very lips and heroically cast their vote with the majority.

The effect was instantaneous but unexpected. The thin Head Professional Scientific Mother had, in one of her lectures, recommended the New Patent Self-Acting Nursing Bottle, and every baby in the park had been supplied with one. I cannot expect you to look at the matter as we did, but in the Union this new bottle was nicknamed the Teaser. It had a patent valve that shut off the food automatically and let us have only a drop at a time, which was very annoying to us, and our mothers supposed that the smashing of bottles was a protest against that particular kind.

This was an unexpected but welcome result of our vote, for it gave them to understand that we objected to at least one folly of the Head Scientific Mother.

Our first concerted act, however, was to establish crying regulations, and in this I was ably assisted by the pug-nosed Williams baby and Sissy Munro, who held the champion belts for long distance crying in our park. I have known Sissy Munro to cry steadily for weeks at a time, but the Williams baby surpassed us all in thinking of new things to cry for. It was he who first thought of crying for the park policeman's badge, and to have an English sparrow to hold, but perhaps his most famous invention was the idea of crying because his mother would not bathe him in the drinking fountain. The important point in the cry is to keep its reason unknown, and I believe his mother is still unaware that her boy wished to bathe in the fountain. But aside from his originality the Williams boy was a reliable and enthusiastic crier.

As the object of the strike was to make our mothers and nurses as uncomfortable as they were making us, I divided the Union into three platoons of criers, two of which should always be on duty, and, while I led one, Sissy Munro and the Williams baby led the others. It was inspiring to hear Sissy Munro leading her chorus into action after a ten minutes' rest. She sprang to her task with a whoop that invariably made passing strangers pause and listen, and she was so enamored of her art that even when her platoon was resting she practiced plain and fancy sobbing, holding the breath, and face-reddening.

By the time to go home we had our mothers seriously worried. I can vouch for this for I was personally searched eight times for pins, patted three times for colic and wheeled up and down the walks six times. My misguided mother supposed when I stopped crying while being wheeled it was because I was pleased, when, in fact, I merely stopped in order that I might give the members of the Union encouraging signs and grimaces.

Before we left the park I instructed the strikers to cry all night, so that their fathers might share in the retribution and I told off six of our older members to have croup, and in order that none might think me too severe in my demands, I myself had croup that night. As I knew I had a strenuous day ahead I took a few minutes sleep about three in the morning, but as I snatched the nap while my father was running for the doctor I did not give him any respite, and he was beautifully fagged in the morning. I sent him to work with a merry salvo of yells.

The next day, while continuing the cries, we interdicted all smiles, all playing with toys and all other amusements that we usually furnish to keep our mothers in good humor, and we one and all refused to take nourishment in any form except after prolonged coaxing, and then only in a listless manner. About the middle of the afternoon, as I was practicing the third degree rites, which consist in putting the right and left feet alternately in the mouth, I heard Dimples Smith, who has her cab stand at the far end of the park, give the "disagreeable stranger cry," and in a moment all the members of the Union were on the alert and ready for the worst. It was the Head Scientific Mother and she passed along the line smiling and bowing to the nurses and mothers. The members of the Union, however, utterly ignored her. Some pretended to sleep, some gave mock attention to their toys and some openly wailed. It was beautifully done and I was swelling with pride when to my horror I saw Dorothy Gertrude Wishart, a member of whose loyalty I had had no suspicion, look up at the Head Scientific Mother and smile sweetly.

I frowned but the misguided member did not notice me, and I rapped sharply for order with my rattle. Dorothy Gertrude only glanced at me, and then held out her hands to the Head Scientific Mother.

My anger was so great that I actually felt an attack of colic coming upon me, and I should have cried out "scab" but that I had no S in my vocabulary. My sorrow was the greater because I always had a certain feeling of attachment for Dorothy Gertrude, partly because we are in a way, cousins, and partly for more romantic reasons. Dorothy Gertrude is what we call a cow-cousin to me. In other words our mothers buy milk of the same dairy. As for the romance, I trust I am not mercenary, but I one day overheard her mother say that Dorothy Gertrude had twenty-six pennies safely invested in a patent savings bank from which money could not be removed except with an axe, and I noticed a few minutes later that Dorothy Gertrude's eyes were a little bluer than any other eyes in the park, and I saw when she coyly put her dainty foot in her rose bud mouth that she had a neatly turned ankle.

Wealth I know does not always mean happiness, but it is an aid to a happy life, and once having been wealthy, a man always appreciates riches. I may say that I was at one time as comfortably fixed as any baby in the park. I had eighteen pennies, two nickels and a Canadian quarter snugly laid away in a bank of which my father was cashier, but in one of these periods of financial depression that come about the time the rent is due, the cashier turned the bank upside down and shook out the funds. He made a verbal agreement at the time to repay his defalcation but I consider the whole amount a loss.

Dorothy Gertrude had, too, shown me quite plainly that such attentions as I had shown her were not unpleasing to her. As her nurse wheeled her past my perambulator one day, I threw my favorite rattle into her lap and I saw her take it in her hand and raise it to her lips. All these things had led me to consider an alliance with her not impossible. It is true that she is older than I, having been born three days before I was born, but she is by no means an old maid and I often think of her as the younger, as I have already a tooth, while she has not.

You can imagine, then, my sorrow when I saw Dorothy Gertrude giving the Head Professional Scientific Mother every sign of love and affection. My feelings were such as I have been told are those of one of our brotherhood who reaches the weaning period and clasps his well-beloved nursing bottle to his lips only to find it filled with vinegar. For a moment I felt that I would give up the fight, resign the leadership of the strike and abandon the park forever.

I saw the Head Scientific Mother pause in amazement, for never before had a baby given her the signs of love and affection. She bent down to kiss Dorothy Gertrude and instantly both of Dorothy Gertrude's hands shot out and grasped the Scientific Mother's hair, gently and firmly. The Scientific Mother held back but Dorothy Gertrude held fast and, crowing and laughing, pulled with all her strength. It was a most artistic hair pull. I could not have done it better myself. Dorothy Gertrude had grasped enough hair to get a firm hold but not enough to distribute the pull, and she swung her arms at an angle that threw her strength on one or two hairs at a time. I really had not thought Dorothy Gertrude had so much science, but my heart overflowed when I saw her joyful eyes turn in my direction for approval and one of them gave me a quick, knowing wink.

It took three mothers to release the Head Scientific's head from Dorothy Gertrude's grasp, and when their combined efforts succeeded Dorothy Gertrude waved aloft two handfuls of pompadour, and to show that she had done it all for the good of the Union she immediately burst into yells of distress. The Head Scientific retreated hastily from the park, and by the laughter of some of our mothers after she was gone we knew that she was losing their respect and sympathy.

That night I named six other members to have the croup, and instructed all to have crying fits, but not to tire themselves out, for the next day was to be the most strenuous of all; it was to be the day on which our battle would be won or lost.

As soon as my perambulator reached the park the next day I called the roll and found all members present. We began the day with a choral cry by all members in unison, followed with colic fits by every fourth baby. While these members were doubling up in the most approved fashion the other members were pale, listless, peevish or sulky as they thought would be most effective. As for myself I lay back and whined pettishly, with occasional kicks at the foot of my perambulator.

It was a very hot day and I was sorry to learn, by chance remarks, that all our efforts were supposed by our mothers to be caused by the weather, by teething or by the bad night we had passed, and I began to be afraid that we would have to develop whooping-cough or measles before our cause could be victorious.

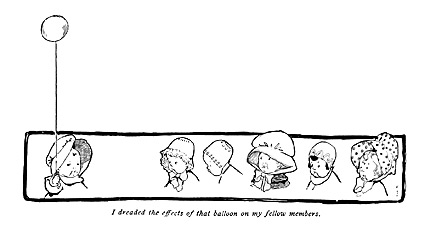

To add to my worry there entered the park at this hour a newcomer in our neighborhood. He rode in an elaborate go-cart with a blue silk sunshade, and his plump face bore a look of self-satisfied fullness that did not harmonize with the efforts of woe being made by the Babies' Protective Union.

The intrusion of non-Union labor is always apt to be disastrous to a strike, and I felt that this newcomer would prove particularly subversive to my discipline because he carried a red toy balloon in his hand. Newcomers to the park, I have noticed, are always wheeled up and down all the walks, and I dreaded the effect of that balloon on my fellow members. I myself could hardly withhold a crow of interest and my hands twitched to reach out for the balloon. You can judge what would have been the effect on the less earnest members.

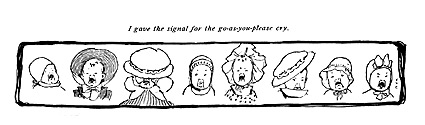

I might have persuaded the newcomer to take out a Union card if I had had time, but to do so would have meant a neglect of the operations I was leading, and that could not be thought of. Either way I saw the strike a failure and the members of the Union going back to work at any terms offered by the Scientific Motherhood Guild, But, resolved on a last strong effort, I gave the signal for the go-as-you-please cry and the whole park burst into wails.

The mother of the newcomer stopped short, and even the newcomer himself looked sober. The new mother turned to my mother and spoke.

"Whatever ails the babies in this park?" she asked curiously. "Are they always as cross as this? If they are I shall have to take Harold elsewhere. I don't want his temper spoiled."

My mother stiffened.

"I guess our babies are as good as any, on an average," she said haughtily, for that is the way park mothers always greet a newcomer, "but they have all been out of sorts for several days."

The new-coming mother took a seat beside my mother.

"It is odd they should all be so cross at once," she said meekly, as a stranger in our park should. "I have never seen so many cross children since last fall. I lived on West Ninety-sixth street then, and one of those persons that preach Scientific Motherhood convinced the neighborhood that our ideas were all wrong, so we tried her rules, and before we were through we had the sickliest, crossest lot of babies in New York."

My mother closed her lips firmly.

As I have said, my parents are quite intelligent, as is natural for persons associating with me daily, and she was able to put two and two together.

Of course she did not let the stranger know that she had learned anything from her. Park mothers never do that. But I had been fed only two hours before and I knew by the way mother hastened to feed me that the shaft had gone home, and before evening every mother in the park had abandoned Scientific Motherhood and our strike was won.

I was glad that my perambulator was pushed alongside Dorothy Gertrude's as we left the park, for I expected her to compliment me on my masterly management of the strike, but she seemed strangely preoccupied with her teething ring and I had to introduce the subject myself.

"All's well that ends well," I said.

"Yes," replied Dorothy Gertrude in the finger-and-eye dialect, "but did you notice how beautifully that new boy squeaks his rubber doll?"

Oh, the fickleness of woman! In my rage I threw myself back in my pillow, and to stifle an angry retort I filled my mouth with the front breadth of my dress. The last I saw of Dorothy Gertrude that night she was waving "bye-bye" to the newcomer.