from Red Cross Magazine

Keeping Up Grandma's Morale

by Ellis Parker Butler

Well, now that the war is over I guess it is all right to tell how hard Jane and I had to work to keep grandma's morale up. Dorothy was no help, because she is fifteen, and all she thinks about is how she is going to wear her hair that day and what boy walked home with her from High School that day. So Jane and I had to keep it up by ourselves -- grandma's morale, I mean.

Of course you know what morale is. Mostly, I guess, it is plenty of wool socks, because then the soldiers know the dear ones at home are knitting fast and fondly even though far, far away. So, when it comes down to grandmothers, morale is knitting socks through thick and thin.

You can see how important it was for my grandmother to have her morale kept up good and high all the time, because father often said that grandmother was the torchbearer of the nation when it came to wool socks. He meant that grandmother was a noble example to all sock knitters, old or young, because she was three pairs of socks ahead of the next best knitter in our town, and father often said he bet we had the prize knitters of the world in our town, both for speed and distance, bar none.

We were all very proud of grandmother, even if she was a little deaf. Of course, one reason she got three pairs ahead at the beginning was because she had learned how to knit when young and agile, while most of the others learned to knit after the war began; but, as father said, it was no airy trifle for grandmother to keep three laps ahead in such a bunch of sprinters after they had learned how to turn a heel without skidding off the needles. Especially Sarah Deering. Father said that, while Sarah Deering might slow up a little on the curves, she was a demon when she opened the throttle and began the mad dash down the home stretch to the toe.

Time and again Sarah Deering got within two socks and a half of grandmother, but grandmother's morale never showed a crack or a stone bruise; and when Sarah Deering loomed up dangerously, grandmother would just submerge herself in her bedroom for a day or two, and when she came to the surface again she would be six socks in the lead and going strong.

So you can easily see that when father and mother had to go to Washington to do war work, and put grandmother's morale in my charge, I knew I had an important thing to look after, because more than once father had said:

"Son, look at grandmother! All is not lost while grandmother's morale is not lost. Let the Germans drive the Russians into the Arctic, the French into the Mediterranean, the Belgians into the Atlantic, the Italians into the Adriatic, and the English into the Channel, but victory will crown us at last if the grandmothers of America do not falter and fail. See her knit. There, son, is the spirit of '76, of 1812, of '61, and of 2:40 on the home stretch! Unless grandmother drops her needles we will win!"

What father meant was not so much that it was good to make eight dozen pairs of socks grow where but one sock grew before, but that it was quite necessary for grandmother to burn with a bright and steady flame, giving courage to all sock knitters.

Thus it was, when father kissed Jane and me goodbye at the station and said, "Good-bye, twins. It's up to you to keep grandma's morale up. Don't let her grow slack and lose the war," I knew it was up to us, although grandmother did say, "Oh! Get along with your nonsense, Henry!"

On the way home Jane and I dropped behind and let grandmother and Dorothy walk ahead, because I wanted to talk it over with Jane and see what we had better get ready to do if grandmother's morale began to fade out. At first Jane said, "Pooh!" and that grandmother's morale would be all right anyway and that I was a silly to worry about it, for I could look and see that grandmother was knitting full tilt even if she was walking and talking at the same time. Jane said that it was silly to worry about anybody's knitting morale that knit like that, not even missing a stitch when a dog came out and barked at her, but I said that was just why we ought to worry. I said that if grandmother was a common knitter, and just knit once in a while, I wouldn't worry about her morale, because she would have enough for that much knitting anyway; but that when she had the kind of knitting morale that she did have, and was a limit knitter, and knit all the time, so that if she stopped a couple of minutes she wouldn't be knitting up to her record, I had a right to worry.

I told Jane that she ought to be serious about it, like I was, and worry about it, because what would father think if he came home and found grandmother was three pairs of socks behind instead of three pairs of socks ahead?

Jane said "Pooh!" and that grandmother wouldn't stop knitting for anything, but I asked her how she knew. I said it was all right enough when father and mother were home to keep grandmother from getting nervous, but all our family knew how nervous grandmother was when you came right down to it, and that it was our duty to see that she didn't get nervous and worry and let that slacken up her morale.

Jane was just going to say "Pooh!" again when one of the airplanes from Mineola came flying over pretty low. It was about as low as I ever saw one, I guess, and the minute grandmother saw it she dropped her knitting and put her hands on the top of her hat and shut her eyes and squatted right down on the sidewalk, because the thing in the world she is most afraid of is something falling on her head. Something falling on her head is her favorite thing to be afraid of, and that's because when she was a child a piece of ceiling fell on her head, and just when she was healing her brother threw a stone at a bird's nest in the crotch of a tree and missed it. So it hit her on the head again. So even to this day, when an English sparrow flies overhead, she dodges. It's involuntary but sure. She just can't help being afraid of anything that is in the air and loose.

So when the airplane was gone we helped grandmother up and we walked home, but she did not knit a stitch all the way, and I told Jane I hoped that would be a lesson to her -- to Jane -- because she had seen grandmother's morale shot all to pieces in an instant, with no sock knitting all the way home while, as like as not, Sarah Deering was knitting right along. So Jane said it was a lesson to her, especially when I explained to her that if grandmother stopped knitting the war would be lost and the Germans come over and own the United States.

Well, when grandmother got home she said it was a blessing to feel a solid roof over her head again and that she hoped she wouldn't have to go out again while those pesky things were gallivanting all over the sky. She meant the airplanes. She said she didn't see why people couldn't conduct a respectable war and not think it needful to invent those awful things that went scuttering hither and yon above one's head. She said that with all this talk of making them bigger and bigger, a body couldn't even feel safe in a house any more, for she supposed if one of the big ones did hit the roof it would come cluttering right through and bring the ceiling down on her head, willy or nilly.

Well, Jane and I sat on the sofa and listened to grandmother, and we saw as clear as day that she was still jumpy because of the airplane that had frightened her. She was knitting, but she wasn't knitting with the spirit of '76. She was knitting jerkily and not at all with a bright and steady flame.

"There!" I said to Jane. "See, smarty? You said her morale couldn't be cracked. Now what do you think!"

"Well, it's cracked, but it isn't broken," Jane said. "You talk a lot about it but you don't do anything. Why don't you do something, if you are so smart?"

So we sat and watched grandmother jerkily knitting and saw that she kept looking at the sky through the windows. For a while neither of us could think of anything to do to keep up grandmother's morale, because it wasn't anything you could take hold of, really. It was just how she felt. So I saw that what grandmother's morale needed was to feel safe and secure from airplanes coming through the roof and shattering down the living-room plaster upon her head. The only way to prove that grandmother was safe was to prove it, so I took Jane quietly from the room and we went up to the third floor where we sleep.

Above the third floor is a place between the ceiling and the roof. You can only get up there through a scuttle with a ladder, but there was a ladder there and Jane and I had been up there before. So we went up again. There isn't any floor, but if you are careful you can walk on the beams and not step on the laths of the ceiling between them, but you have to keep bent over, the roof is so near.

The reason we went up was to see that the beams of the roof were good and strong, so we could tell grandmother that no airplane could ever break through, even if it fell spang onto our roof. We looked at the beams and felt them and tried to shake them, but they were good and solid. They were solid enough for anybody.

It was dark and dusty up there, but Jane and I sat on the ceiling beams and talked it over and said we could truthfully tell grandmother that even the biggest kind of airplane couldn't break through unless it fell from very, very high. Even if it fell nose down it couldn't come through, because the roof timbers were so close together.

"If she don't believe it," Jane said, "we can offer to bring her up here and let her feel the roof herself. Of course she won't come, but it will make her feel sale if we offer to let her."

So we went down.

When we got to the second floor I stopped Jane because I had thought of something else. It was about ceilings and that we ought to prove to grandmother that the ceilings in our house were safe and sound. Jane thought so, too.

"Because," Jane said, "if grandmother knows they are safe and sound she won't be afraid that they will fall down on her, no matter what happens, and then she can knit in peace."

"And not worry," I said.

It was too bad for the dishes that Nora had already set the table, but the reason we picked out mother's room was because there was a rocking chair in it, and the rockers wouldn't hurt the floor as chair legs might. Jane took the chair by the arms and I took it by the back, and we thumped the floor with it. We thumped vigorously, because that was the only way to prove that the ceiling would not fall. It was Dorothy coming in that stopped us. She was quite out of breath from running up the stairs, and she tried to jerk the chair away from us.

"Stop that!" she yelled at us. "For goodness' sake, stop! Are you trying to scare your grandmother to death, or what? She's crawled half under the sofa and you are driving her frantic with fear!"

We hadn't thought of that. I guess, when we thought of it, we were so scared that we let the chair fall. Anyway it fell, and then we heard it. The dining-room ceiling falling into the dinner dishes, I mean.

"There!" said Dorothy. "Now we will never get grandmother to come out from under the sofa!"

But we did, or what was the same thing. Nora and Dorothy lifted the sofa off from over her.

Her morale was very, very bad just then. It looked for a while as if she would never have any again. We had to carry her dinner to her room, and she ate very little, keeping her eyes on the ceiling continuously. Both Jane and I were very contrite and Jane was tearful, and we begged her pardon many times, but she did not have morale enough that night to knit at all.

I was afraid she would never knit again and I told Jane so; but the next morning, when Jane and I were composing a telegram to father, telling him that he had better hasten home because grandmother's morale was at its last sad ebb, grandmother came out of her room, and she had her knitting.

She gave up sitting in the living room that day and sat in the dining room where there was now little or no plaster to fall, and she knit more or less, but mostly less. Jane and I remained away from her quite a good deal that day, because her morale seemed to weaken when we came into the room, and Dorothy sat with her, mostly to tell her there were no airplanes hovering above.

Jane and I peeked in at the door many times, for we longed to repair the damage we had done to dear grandmother's morale, but it was not until just before dinner that we had a chance. We were approaching the door carefully when Dorothy came out with a rush. She had the evening paper in her hands and she stopped short in front of us.

"Now, listen to what I tell you, twins!" she said, as if she meant it. "Don't you ever let grandmother get the newspaper before I look through it! Understand? Well, remember it!"

She went upstairs then, taking the paper with her, and Jane and I went into the dining room, where grandmother was sitting in her rocking chair. She was knitting, but not with vigor and vim. She looked at us kindly, as if all was forgiven, however.

"Well, dears?" she asked, for I guess we looked as if we wanted to talk to her.

"You needn't be afraid of airplanes in this house, grandmother," I told her.

I had to shout it rather loud, because she don't hear well.

"No, you needn't," Jane said. "It's a safe house."

"We know it is," I said, "because we went up under the roof and we looked at the beams, and felt them --"

"And they're solid as iron!" Jane said.

"Yes, and an airplane couldn't fall between the beams if it tried," I said, "they are so close together. No old airplane out of our sky could fall between them. We know, don't we, Jane, because we looked."

Just then grandmother sort of jumped.

"What's that?" she asked, dropping her knitting into her lap.

It was Nora grinding the coffee, and we told her.

"I thought it was an airplane," grandmother said, and she began to knit, but far from placidly.

"Pshaw! You don't need to be afraid of airplanes when we have a good roof like ours," I told her. "There can't anything bigger than a bomb fall through our roof."

"What? Bomb!" grandmother asked.

"Bomb!" I shouted. "Bomb! Nothing but one could come through our roof. Of course a bomb could, between the beams, where there isn't anything but thin boards and shingles. Of course, a bomb could come right through the roof --"

Well, grandmother got right out of her chair and went under the dining-room table and threw her skirt over her head and held it there with both hands. We tried to get her to come out but she only edged in deeper. Even Nora couldn't get her to come out, and when Nora called Dorothy, she did not help much.

"Now, what!" she exclaimed in the mean way she does when she is very, very provoked. "Now, what! What on earth have you been doing now?"

"Nothing," I said. "We haven't been doing a thing except trying to keep grandmother's morale up, and father told us to."

"He did so!" said Jane.

Dorothy just threw her hands as if she was trying to throw them away.

"What -- what have you been doing?"

"I just told her the roof was good and strong," I said, because I was mad at the way she was blaming everything on us. "I didn't do a thing but tell her no old airplane could fall through our roof except a bomb --"

"Ye gods!" Dorothy cried, as if all hope was lost forever. "Bombs! Bombs falling through the roof! And I just found her frightened half to death over this silly warning in the paper that the German submarines might be carrying airplanes that would try to drop bombs! I just managed to persuade her that no bomb could ever break through our roof!"

It looked, indeed, as if grandmother would live under the dining-room table from then on, until the war was over, and it seemed quite plain that, in spite of all we had tried to do, her morale was at the lowest ebb possible, if not gone entirely, but at that moment grandmother removed her skirt from her head.

"I'm not afraid, mind you!" she said. "I'm not a mite afraid."

"We know you're not, grandmother," Dorothy said.

"Not a jot or tittle!" said grandmother. "It is memory. Unconsciously I dread anything that may fall on the top of my head. I can't help it."

"We know," Dorothy said.

Well, it would be an awful thing if I had to say that grandmother never got back her morale, because then I would have to say the Germans won the war, but everybody knows that isn't so. But it might have been so if Sarah Deering hadn't come over. She came right in without ringing, like she always does, and she did not have her knitting. She had something else. She had a souvenir her brother had sent over to her from France. It was a German helmet -- a steel one.

Of course she was surprised to see grandmother under the table; but when Dorothy told her why grandmother was there, she laughed.

"Then this is just what you need, grandmother," Sarah Deering said, and I guess grandmother didn't know she was joking, because she took the steel helmet and tried it on. It fit her pretty well. She tried it by shaking her head, and I guess she was satisfied with it.

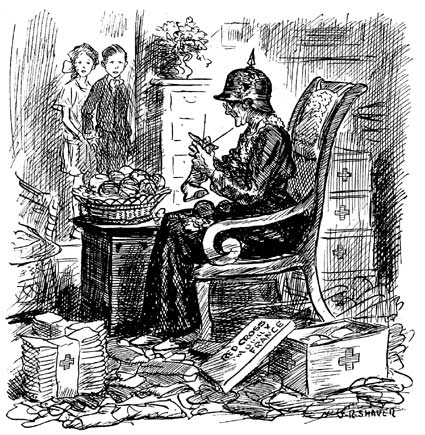

"Help me out from under this table," she said, and we all helped her. She patted the helmet on top, and then she sat in her rocking chair and took up her knitting. "Thank you, Sarah," she said. "This is just what I have needed all my life. I wonder I never thought of it before. It is the most comfortable hat I have ever had."

Then she began to knit, and by the way she knitted Jane and I knew her morale was all right again. We knew her morale was sound and solid all through once more. She was knitting like 2:40 -- on -- the -- home stretch!