| ||

| ||

from American Girl

Gull Ledge

by Ellis Parker ButlerThe island was beautiful, with its thickets of pines and swales of fair land and well-scattered summer homes, but the ledge was but a reef of inhospitable rock rising like the bones of some prehistoric sea monster above the waters of East Penobscot Bay. The shack on the ledge, a mere shanty built of odds and ends washed up on the ledge, was the color of the rock itself, and many were those who, sailing the bay in their pleasure boats, saw it and did not see it, thinking it but a part of the ledge, for no one would have believed that a human habitation would be built in such an impossible and inhospitable spot.

No spring pierced the rock to give water for drinking and cooking. A barrel stood by the door of the shack and when it was empty the two girls, Jean and Jasey, twins, took a pail and crossed the bar that at low tide connected Gull Ledge and the island, going back and forth until the barrel was full again. It was when going back and forth thus, or when digging clams on the bar alone, or when they sat on the point of the ledge out of hearing of the old man and old woman in the shanty, that they talked.

They were strange wild creatures, those girls, with black hair, and eyes as black as their hair, as quick to take fright and fly to the safety of the shanty as timid field animals to seek the shelter of their holes. When, now and then, someone on the island came upon them filling their pail at the spring, the two girls straightened and gazed and then turned and fled into the pines, not to venture back to the spring until no one was near. Brown as Indians, their only clothes were patched together of what drifted ashore on the ledge, bits of bagging and sailcloth.

On this day they had been startled at the spring by a girl of something more than their own age. Bent down scooping up water in their cupped hands to fill their pail, they had not heard her approach until she was standing just above them, and when they leaped to their feet they stood staring at her, as she stared at them, before she spoke.

"Oh, won't you wait a minute?" she said. But at her first word the twins darted for the shelter of the pines, shy as wild deer, and they hid there watching her as a tall man in golf clothes came toward her.

"It was those girls I told you about from the ledge, father," she said. "They were here just a minute ago. You'd feel sorry for them, too, if you could see them."

"And you think we ought to look after them, do you?" He put his hand on her arm and they moved off. "Well, we'll see."

But the twins were not listening. They were looking at the girl -- at her clothes, her hat, her shoes and the neat waves of her bobbed hair. They had seen girls before, but never so close at hand. Not until she was gone did they return to the spring.

"You seen her good?" Jean asked. "I ain't done nothin' but look at her. That's how I'm goin' to be -- someday; like her."

"I got a longin' for to, too," Jasey said. "That's how I want to be, too. She had shoes on -- shoes. Right in summer, too, Jean. I don't reckon I'll ever have shoes in summer, but I wisht I had shoes in winter. And a hat."

"If you didn't see 'em you wouldn't believe there was nobody in the world like that," Jean said. "They ain't the same as pap, and they ain't the same as mom, and they ain't the same as us. They's folks. They's land folks. We ain't nothin' but --"

She could not find a word to express old man O'Shonessy and his wife and themselves, but Jasey supplied it.

"Gulls," she said. "We'm gulls, roostin' on Gull Ledge, Jean. Come on. We got to fetch a lot more water yet or mom'll beat us fearful. Git holt."

With the pail between them they started across the bar toward the ledge, but midway Jean bent down and Jasey let the pail rest between them.

"Come time we're full growed," Jean said, "we can be like her. We can handle mom, the both of us, come we're full growed, and she won't dast to try to beat us. We can dig clams, Jasey, and sell 'em to folks, and be like her we seen. We can git clothes and shoes and all for us, and be like her."

"We can git clothes and shoes and a hat and all," Jasey said, "but that ain't enough to make us like she is. She's l'arned. You got to l'arn things out of books into your head to be like her. Say if we does git clothes and shoes, we ain't but gulls with clothes and shoes on. Folks has to have l'arnin' out of books to be folks, Jean."

Jean turned her head and looked back toward the island where they had seen the girl who was so unlike themselves.

"Yes," she agreed. "It ain't just what's onto her; it's what's into her, too, makes her the way she is, I reckon. But we can git l'arned, too, Jasey. We got to dig more clams when we start diggin' --"

"You can't dig enough clams," Jasey said wisely, shaking her head. "For folks to be l'arned right folks's folks has to start diggin' clams or something, and savin' money from it, before folks is even first washed up on shore. An' pap and mom never did start. An' they wouldn't give us l'arnin' if they had. They don't cater to it."

"How much money do you think it takes to git a body real l'arned?" Jean asked.

"I don't know. Heaps, I guess," Jasey said, bending down to grasp the handle of the pail. "Fifty dollars, I shouldn't wonder."

Jean sighed. That was a tremendous sum -- fifty dollars! It was seldom the O'Shonessy's had a dollar to their combined names, and neither Jean nor Jasey had ever possessed so much as a copper cent of their own.

"Fifty dollars for me, and fifty dollars for you," Jean said. "I don't know how much that is, Jasey, but it's a heap of dollars. I reckon it's more dollars than pap ever had in his whole born days."

"I 'low nobody ever had two heaps of fifty dollars at one time," Jasey said. "Grab aholt of the pail, Jean, and git goin' or mom'll give us a riggin'. I reckon gittin' l'arned ain't for such as us, no way."

"Jasey, wait!" Jean cried, ignoring the pail. "I'm got a notion! Us don't have to have two heaps of fifty dollars all at once! Us can git us l'arnin' the way us fills the water bar'l -- handful by handful into the pail, and pail by pail into the bar'l. Dollar by dollar into us, Jasey. Jasey, I'm goin' to git l'arned! Blast me if I ain't, Jasey! Somehows I am! And you, too, Jasey!"

The eager enthusiasm of her sister blew the spark of ambition in Jasey, too, and she snapped her finger. It was a trick she had when she was excited.

"Blow me down, Jean, if I don't git what you git," she declared. "Us'll sure git l'arnin' somehows. And we can start in when we git back to the ledge. Us can cut our hair off."

"'Cause why?" Jean asked.

"Like her," said Jasey, pointing back to the island with her thumb. "I reckon folks has got to cut their hair short-like on their heads for to let the l'arnin' git in. Like her yonder. Us can make a start right now that-a-way. You cut mine, and I cut yours, and byme-by us'll start gittin' dollars somehows. Us'll just wait and see if 'tain't so."

They talked excitedly as they walked the rest of the way to the ledge, eager to begin being "folks," and fortunately this pail of water was the last needed to fill the barrel. When they entered the shack Mrs. O'Shonessy was in a temper, as she usually was. The old man O'Shonessy was cowering outside the door. Such living as they had he made by clamming and fishing, but he was too lazy to work except when driven to it, and the old woman often whipped him when she fell into one of her rages, just as she whipped Jean and Jasey. Now, as Jasey darted for the shears that lay on the floor under the bed, the old woman turned to her and would have grasped her arm, but Jasey dodged and was out of the door.

The one door of the house opened into the kitchen, which was also the bedroom of the old couple and the living room as well. Above, reached by a rude ladder of driftwood, was a shelf large enough to be called a room, for it had a bag of hay on the floor that served Jean and Jasey as a bed. This was all the house there was, and whoever originally built it must have had a hard time finding a place on the ledge for even such a miserable structure. A part of the floor of the kitchen was the rock of the ledge itself, but the rear part of the floor was made of old ship planks. Under these the ledge fell away abruptly, but a high pile of stones had been built up on which to rest that end of the shack, almost all the loose rock of the ledge having been so used. When this old shack had been first built no one knew, nor for what it had been used. Some said it had been a rest for smugglers even before the Revolutionary War and, later on, for pirates, but it had been washed down and rebuilt many times and was now a patchwork of broken boards, old tin and even legs of sea boots, flattened out and nailed here and there to cover up gaps and holes in the old walls.

Followed by the yells of the old woman, who came to the door to shake her rope at them, Jean and Jasey hurried to the far point of the ledge. At low tide the ledge stood well out of water, the recently submerged rocks all covered with dripping green seaweed, but at high tide the ledge was almost entirely covered by the water, and when unusually high tides swept into the bay they invaded even the shack, the water covering the floor to the depth of an inch or more.

The tide was now at the ebb and Jean and Jasey trod carefully to the point of the ledge and there performed the first act of what they supposed was the way to an education and a decent life. Jean knelt on a pad of soft kelp while Jasey snipped at her long black hair with the dull shears. As she worked Jasey talked, and her language was a strange one to be heard on a Maine reef. Phrases of the southern mountains, of the coast and of New England mingled in the queer dialect the O'Shonessy's spoke.

For this there was a reason. O'Shonessy, drifting from somewhere into the hill country of Tennessee, had married one of the hill women, but he was a bad man and perhaps she was no better. He stole a horse and fled by night, taking his wife with him. Possibly he had been a coast man and had fled to the mountains because of some other crime, and probably his name was not O'Shonessy, for he spoke no Irish dialect. However that may be, he began drifting up and down the Atlantic coast, now at one place and now at another, moving on when his presence became too unwelcome, managing in spite of his laziness to keep possession of his one-masted fishing boat and his dory, and with the old woman and the two girls, Jean and Jasey, he had come to roost at length on the ledge.

Whence the twins had come was a mystery. Of their coming the old man would never say anything, and the old woman said they had "come driftin' in." Everything the miserable couple possessed, except the rusty stove, had "come driftin' in" -- the boxes used for chairs, the ruined bed, the firewood. Whether the twins were their children, or had been stolen, or had indeed drifted in, no one was ever to know, but that very night Jean and Jasey were to know to what use O'Shonessy and the old woman meant to put them.

The girls, returning to the shack, more than expected to be beaten for having cut their hair, but the old woman said nothing, giving them only a glance and grabbing the shears from them viciously.

"If you'd a lost them shears I'd a whaled you good," she cried, and said no more. It made no difference to her whether they cut their hair or not, but that night when Jean and Jasey lay on their hay sack above the kitchen, listening to the rising wind, the old man and the old woman sat long below, smoking their pipes.

"You mark my words," the old man said, "we get a blow tonight. I know the signs, I do. She's a comin' strong tonight. Wisht we was on mainland, I do."

"Ain't I wisht it always?" the old woman demanded. "Roostin' on a ledge like mis'able gulls! Well, we can be on mainland right soon. We can be on mainland next week, I'm a-sayin'."

Up above Jean grasped Jasey's hand, silently making sure she was awake and listening, and they held their breaths to hear what more was to come.

"They old enough to fetch pay, think ye?" the old man asked.

"They'm old enough to put out to work," the old woman told him, with a grim determination in her voice. "Old enough to hire out to work fields. I raised 'em right, I did, with a rope end, and what they earn we git! We'm goin' to take things easy now, off'n their pay."

"We got to be keerful who we put 'em out to," the old man said. "Some folks is fools; some folks is like to put notions in their heads an' get 'em thinkin' they want to be eddicated. Then they ain't goin' to give us their pay."

"I ain't born yestiddy," the old woman said with a sneer. "I ain't puttin' them out to no decent folks. And us gits the pay." The twins clung to each other in sudden fear of this unknown future, but what the old woman said next was lost in the whistling of the wind.

"I says we get a blow tonight," they heard the old man shout, and then the clamor of the wind increased. Through the cracks between the boards the wind blew with increasing intensity, not coming in gusts but continuously and with continuously greater force. The light, which was dim in the place where Jean and Jasey lay, went out as the wind tore a slab from the side of the shack and blew out the flame of the oil lamp, and the old man fumbled for his lantern.

He struck match after match, but finally he had it alight and the twins could see again. They crept to the edge of the floor of their shelflike room and peered down. The old woman sat on the edge of the tumble-down bed, her hands clasped in her lap and a look of fear on her face, for she had never grown to be unafraid of the storm when it swept across the water.

The old man showed no such fear. Carrying the lantern he moved here and there, finding his slicker and nor'wester, putting his feet into his broken storm-boots. His thought was of his fishing boat, perhaps not safely moored against such a blow, and he was preparing to go out into the storm.

The tide was high now and if the storm was not too angry he could run the boat across the bar to safer shelter in the lee of the ledge, but as he turned to the door the old woman cried out and ran to him and grasped his arm. She was afraid to be alone in the tempest, but he threw her hand off his arm and opened the door. The old woman turned and grasped the ragged blanket from the bed and threw it over her head and followed him out into the storm. She would not be left behind.

Instantly the door, weakened by many such furious storms as this, opened outward, and slammed shut with a violence that tore it from its rusty hinges, splintering its boards, and the wind rushed in like some wild animal bent on destroying all it could reach. In the utter darkness, Jean and Jasey could hear the clatter of the few pans as they were swept from the shelves, the clatter of the box-chairs as they were blown across the floor and the creaking of the broken door.

Never had such a gale invaded Penobscot Bay. The air, driven at tempest speed from the source of storms in the region of the West Indies, was of an almost tropical hotness. The shanty shook and swayed.

"Jasey, we got to git down from here," Jean cried. "I'm skeered we'm goin' to blow over."

They had no need to dress, for they slept in their scanty clothes. They felt for the ladder and, one following the other, backed down to the kitchen. Jean went first and as her foot reached down she uttered a cry.

"The water's in," she said. "It'm up to my ankle already on the floor. I'm skeered, Jasey."

She had good reason to be frightened. The gale was increasing, the wind ripped the tin patches and the loose boards from the roof and sides of the shanty, and the waves -- driven by the gale -- were now beating against the windward side of the shanty, and no sooner had Jasey stepped down into the water beside Jean than there came a crash against the shanty that crushed the wall and would have swept the miserable structure off the ledge had not two of its posts been set deep into the pile of stones on which one end of the shanty stood.

The twins grasped each other and stood in fear, for the blow against the shanty was now repeated again and again, and they knew what it must be. Old O'Shonessy's fishing boat, dragged from its mooring, was beating itself to pieces against the shanty, and being hurled against it again and again by the waves that rode the wind-heaped tide.

The swinging of the shanty threw down the stove and the fire hissed out in the water which was now almost to the girls' knees, and old O'Shonessy came staggering into the shanty with the old woman clinging to his arm. The voice of the old woman was a wail.

"What we goin' to do? What we goin' to do? Us'll drownd like rats!"

"Shut yer bawlin'!" O'Shonessy shouted. "We got the dory yet. Come on!"

He pulled his nor'wester more firmly on his head and started out, and Jean cried to him, begging him to wait for them, but when she ran toward him he threw back his arm so that the blow knocked her down and, with the old woman still clinging to him, he went out. Neither of them was ever seen again; no doubt the dory was unable to weather the seas.

The constant pounding of the fishing boat against the shanty now began to have its inevitable effect, and as the boat pounded itself to pieces it loosened the structure of the shack and the gale tore away whole boards.

"I guess us is as good as dead, Jasey," Jean said. "Pap has done quit us."

As the shanty slewed around it was pushed more and more off the rock that had been the solid floor of one end of the kitchen, and as the rock fell away the water in which the girls had to stand was deeper. They were presently in water to their waists, and seeking a spot where it was shallower they stumbled to the end that stood on the heaped loose stones. But they had hardly found a precarious safety by grasping the post before the gale lifted the shanty and threw it, a mighty wave striking it at the same time.

As if torn away by a giant hand all the far part of the shanty was wrenched away and the post to which Jean and Jasey clung was bent far over, carrying them down with it until they were almost flat on the rocks. With this final effort the fishing boat's mangled remnant washed over the ledge and was gone. Except for the toppled post to which Jean and Jasey clung, the Gull Ledge was rid of all proof that a shanty had ever stood there.

As if, however, the demolition of the shanty had been the one thing the tempest had sought to accomplish, the gale now lessened. The waves still washed across the ledge and again and again Jean and Jasey, clinging to their low fallen post, gasped and strangled as their heads emerged from the wave that had swept over them. So the night passed. Toward morning the gale blew itself out, shifting out to sea, and with the falling of the tide the ledge raised itself once more above the waters and Jean and Jasey lay exhausted on the heap of rocks. They were wet and cold and their teeth were chattering when the coming of morning brought enough light for them to see their surroundings, and Jean raised her head to look.

"Jasey! Jasey!" she screamed so wildly that Jasey was almost more frightened than she had been during the terrible night, but Jean was bending down to lift one of the loose rocks that had been pried up when the post had been bent over. "Dollars!" Jean screamed joyously. "It'm dollars, Jasey! It'm gold money! Oh, I reckon we'm got fifty and fifty and fifty dollars, Jasey!"

They were dollars indeed! Or dollars and doubloons and ducats and who knows what strange old-fashioned golden coinage? And who knows what old pirate or buccaneer or smuggler had hidden his gold on Gull Ledge, heaping this pile of stones over it and building the shack to drive suspicion from it? And who knows how many years the chest of gold had lain there before the tempest used the shanty and the post as a lever to upheave the stones and crush the chest and lay the treasure bare?

The sight brought life back to Jasey too. "Jean! Jean!" she cried in ecstasy scooping up a double handful of the golden coins. "Us has got dollars! We'm goin' to have clothes! We'm goin' to have hats! We'm goin' to have shoes!"

Jean threw her arms around Jasey's neck and kissed her again and again.

"Us is goin' to be l'arned, Jasey!" she exclaimed rapturously; "Us is goin' to be folks! Us'll go see that girl by the spring."

She raised her face to the gulls that were circling over the ledge. "You can have the ledge," she told them, "us don't want it never no more nohow!"

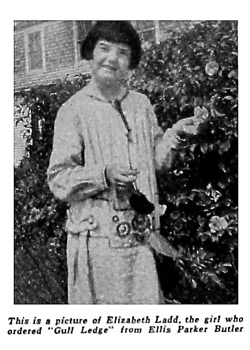

The telegram telling Elizabeth Ladd that her letter was one of the twelve selected to be made into stories reached her on her thirteenth birthday. "I live on an island," she says, "and have a long way to go to school, so I spend most of my time on the way telling stories.

"I hope Mr. Butler likes my twins, for I'd just like to be them and live on the ledge, which is a real place in Penobscot Bay, but really only gulls live there." Here is the order Elizabeth wrote:

"I would like a story of adventure, written by Ellis Parker Butler, about:

"Old man O'Shonessy, who is a fisherman but very, very lazy.

"Old woman, his wife, who is very quick tempered.

"Jean and Jasey, their children. They are twins, both have black hair and eyes. What clothes drift ashore are all they have.

"They all live on a ledge in East Penobscot Bay, which at low tide is connected by a bar to a small island, but at high tide the ledge is almost covered and is fairly large. The house is built in the middle of it, on a high pile of rocks, but even there at very high tides the water comes in on the floor.

"The house is just a shanty built of odds and ends of things washed on to the ledge. A ladder goes upstairs to a bedroom. The children sleep together. The beds are made of hay and old blankets.

"They have little money, and live by fishing and clamming, but the old man is too lazy to do much, and the old woman has to whip him very often."

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 6:24:02am USA Central