from Leslie's Monthly

In the Next Cot

by Ellis Parker Butler

Wilkins was gliding up the avenue in his palpitating motorcar, keeping one eye on the path ahead and one on the walk, when he saw, just ahead of him, Willy and the Stony Lady, leisurely walking, and he turned his car into the curb and drew up beside them.

The Stony Lady, who was so called because of her hard, hard heart, was sweet and fair and merry, and her hard, hard heart was as tender as a maiden's heart dare be, but Wilkins and Willy had decided that it was a hard heart because it was a hard heart to obtain. As for Willy, he was -- just Willy. Everybody liked Willy. Even the Stony Lady liked him. She liked him with all her heart, so, of course, she had no heart left with which to love him.

"Afternoon!" said Wilkins, cheerily, pushing up his goggles. "Howdy, Willy! Thought perhaps I'd run across, or over, one or the other of you. Everybody seems to be out today. "Get in and I'll take you to -- wherever you were going."

The Stony Lady looked at Willy questioningly.

"Would you?" she asked. "Would it be risking a human life foolishly?"

"O, as for me," said Willy, "I'll get in. I'm glad to die. What is life worth to me without --"

"Excitement?" interposed the Stony Lady, hurriedly. "You have the gambler's instinct, abnormally developed if you are so willing to wager your life for a ride with Mr. Wilkins. I will get in, too, but only to exert a restraining influence on Mr. Wilkins."

"Do you really trust yourself with me?" asked Wilkins, as if the thought overpowered him. "Now, if I could only persuade you to --"

"Trust yourself with me for always," was what he was going to say but she intercepted the words.

"To run the car?" she asked. "No, Mr. Wilkins. I cannot pamper your weakness by assuming your responsibility. Go ahead, please."

"I have to back first, you know," explained Wilkins, "unless you want me to run over the curb."

"Why don't you?" asked Willy. "You might as well smash up the car that way as any other."

The Stony Lady eyed Willy haughtily.

"You might at least let Mr. Wilkins break his machine when and how he pleases," she said, "You will please back just as you intended before Willy spoke. Do not pay any attention to him."

"I'm not," said Wilkins.

"O!" said the Stony Lady, "I thought that was why you were not backing. Why don't you back, Mr. Wilkins!"

"That rear wheel," Wilkins explained with exasperated calm, "is wedged so tightly into the curb -- if Willy was a real man he would not sit there like a dummy. He would get out and push a little."

"I will get out and push," said the Stony Lady, heroically. "Shall I have to push far?"

Willy crowed gleefully.

"If you can't back the thing," he said, "why don't you try going forward? Never mind the curb. Is it one of the rules of the game to back first? If you don't have to back, I'd go forward, if I were you."

Wilkins blushed.

"I hadn't thought of that," he said, and he tried it. The car moved forward, negotiating the curb with a slight jolt.

"Now," he said, more happily, "where were you going!"

"Nowhere in particular," said the Stony Lady.

"I shall take you there." Wilkins declared, positively. "I'm always just there when I break something. You don't mind walking back?"

"We would rather walk than ride back with you, Wilkins," said Willy spitefully. "It may not be so exciting, but it is safer."

"Must you two children always quarrel when I am with you?" asked the Stony Lady. "Have you no common ground on which you can meet in peace?"

"Have we a common ground, Willy?" asked Wilkins innocently. "Do you know anything that both of us like?"

"Do you mean something that we -- admire, so to speak? Something that we both feel an interest in?"

The Stony Lady shut her lips firmly and opened them just enough to say: --

"Now you are going to be silly."

"That is what she means, Willy," Wilkins said. "Try try think of something we both adore."

Willy thought deeply.

"From where I am sitting," he said at length, "my eyes are looking straight at the back of the one thing that Wilkins and I desire. I can't see it's face, because it is looking angrily at the back of the cab into which Wilkins will bump in a moment or two. But I can see its hair, one golden lock of which, like a sunbeam escaped from prison --"

The Stony Lady's hand quickly touched the hair at the back of her head.

"It's not true," she said, "and you two are ungallant to attack me when you know I can't jump out of this car. It is taking a mean advantage. You never get me alone but you pester me with --"

"Well, then," said Willy cheerfully, "why don't you marry one or the other of us and get rid of us? We have asked you often enough. At least I have."

"Me, too," said Wilkins. "How does the account stand now? Is Willy ahead or are we even?"

"The reason, or one reason, that I don't put you out of your misery," said the Stony Lady with a seriousness that meant either that she was deeply in earnest or not at all in earnest, "is that you don't either of you really know what you want or why you want it. You are two children and you will never be anything else. When I marry I shall choose a strong, forceful man, who has some reason for living, and who will want me because I am needed to fill out his life. I hate to be wooed as if I were a toy you would rather like to have, but that you could joke about if you did not secure."

Wilkins glanced at her face and jerked his lever quickly, causing the car to swing recklessly around a slow going wagon into the park entrance. The Stony Lady swayed against him.

"Pardon," he said, but the fun had left his eyes and he drove his car ahead at greater speed.

"You two remind me of children, nothing more," said the Stony Lady. "Did you ever hear a baby awaken in the night and cry and cry and cry for a drink, after it had been given drinks and drinks and drinks? All babies are that way. They all want things they don't need and oughtn't to have. You two are the same. You cry for me as if I were a drink. You simply haven't anything else to cry for, so you cry for me."

Willy was leaning forward to catch her words.

"If you got me," she continued, "you wouldn't be pleased. You wouldn't care for me. I wouldn't satisfy you, because there is nothing in you to satisfy. You would still cry for other things you don't want."

"I admit the logic," said Willy, "but object to its application. Can't speak for Wilkins, but I should never cry again. I'd forever coo blissfully."

Wilkins said nothing. He was threading his way in and out among the carriages in the park, and it may have been that this required all his attention.

The Stony Lady had been courted in this light and airy manner by these two for more months than I dare tell you, and by Willy longer than by Wilkins. The Stony Lady had aided and abetted Willy's nonsense. Everybody did. Thus, through his airy love making, she had come to treat both men lightly, and had adopted a tone of frivolity in fighting their advances.

This vein of seriousness in the Stony Lady was new. It made Wilkins feel that he had been making a free fool of himself. He had been using fireworks instead of thirteen-inch shells. He had not quite appreciated the Stony Lady.

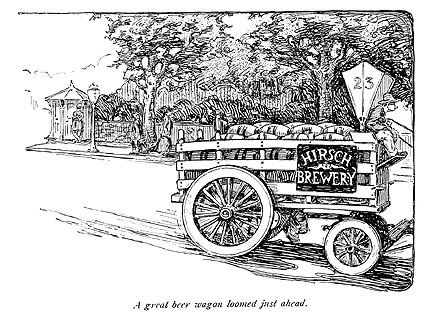

As the car darted from the upper entrance of the park into the broad path of Seventh Avenue, Willy was still chattering gaily, as much to himself as to Wilkins and the Stony Lady, for they had fallen into a thoughtful silence. Wilkins was pushing the car to a reckless speed, for him, and the mounted police eyed the car doubtfully. A great beer wagon with high piled barrels loomed just ahead and then, quite suddenly, the car seemed to rise in the air with a noise of rending wood and metal, followed by the sound of empty barrels dropping hollowly to the ground.

When the ambulance arrived and the surgeon forced his way through the crowd, he found the Stony Lady laughing hysterically at Willy who was wiping the dripping blood from his nose upon a piece of derelict newspaper. His head was bound in a section of the upholstery of the motorcar. Ready hands had carried Wilkins to a nearby drug store, where half a hundred men, women and boys tried to catch glimpses of him through the plate glass of the doors. Wilkins had not yet recovered consciousness.

The ward in which Wilkins lay when he regained consciousness was unlike his previous conceptions of a hospital. The ceiling, at which he found himself staring, was in a series of small arches, painted in a glossy yellow that reflected the light annoyingly. The walls were of a sickly blue, and the floor was the hue of a battlefield after the carnage. The upper portions of the windows were set with blue glass that was out of harmony with every other color in the room.

The cot on which he lay was of iron and there were eight or ten other white iron cots arranged along the walls, with only room between for small iron tables. A walnut board, with a clamp to hold the chart for the temperature record was hung at the head of each cot and through everything and over everything prevailed the penetrating odor of iodoform.

Willy was in the next cot! He was a sight to gladden the eyes of a rival. Around his head were others of those white bandages that seemed to be the favorite headdress in this corner of the world, but the great touch of art was his left eye. Blues and greens and blacks in deep tones formed a decorative masterpiece below that left eye, and gave him a sinister appearance that jeered at his cheerful smile,

"She --?" queried Wilkins, in a voice that he was surprised to find weak.

"O.K.," said Willy. "It never touched her. You couldn't have done it better if you had tried."

"You look in a bad fix, Willy," Wilkins said, when he had assimilated the good news.

"Oh, yes, pretty bad," Willy agreed. "But nothing to what you are in for."

"Why?" asked Wilkins. "What happened to me?" It was just beginning to occur to him that he, too, was hurt -- that he must have been hurt or he would not be here in a hospital. He supposed it was a hospital.

"You got a bump on the head," said Willy. "The professor and I haven't decided yet whether we will make you a case of concussion of the brain or just plain headache. Then you have the prettiest compound fracture of the lower leg that the professor and I have ever seen. You'll be here some weeks with that, even if your head turns out to be useable. Head doesn't feel numb, does it? You can understand what I am saying?"

"My head is all right," said Wilkins. "I'm sorry about this leg, though. I suppose nobody knows we are here. No one has sent us any -- flowers or -- anything yet?"

"She hasn't yet," Willy assured him maliciously. "Do you think she ought to send them as a token of her thanks to you for spilling her into the street, or because you rid her of two babies at one shot?"

Wilkins had been examining his state. He found that his leg seemed as permanently attached to the bed as it was to his body. It appeared to be encased in boards and tied to the foot of the bed.

"They must be afraid I'll try to get away," he grumbled.

"The keepers of this menagerie are going to turn me loose tomorrow," said Willy.

Wilkins groaned and then smiled.

"Black eye and all?" he asked.

"Have I a black eye?" asked Willy. "What did you tell me for! I have been so happy thinking of you lying here while I walk with the Stony Lady. Notice I said 'walk,' Wilkins."

"If she would walk with that eye of yours --" It was beyond Wilkins' power to express his disdain.

"I can paint it," Willy declared. " I am a hero anyway, and I ought to have some scars. I picked her up. You didn't. You didn't even think of her."

"How could I?" Wilkins began and then paused. "Willy," he said, "I think we have been taking the wrong way with the Stony Lady. I wouldn't usually be so unselfish as to call it to your attention, but I spilled you and gave you that eye. It is a wonderful eye, Willy. I never saw a more artistic job. I'm proud of it."

"I know what you are working around to," said Willy. "You are going to tell me we have been too frivolous. You are frightened because she took a sober spell this afternoon. But remember that she was in your motorcar, with you at the helm. All women grow serious in the face of peril."

"You'll do as you please, I suppose," said Wilkins, "but when we get out of here I shall not treat her as a spoiled child again. I shall take her seriously."

"Thank you. I'll take her myself if I get the chance, seriously or not," laughed Willy.

Wilkins was glad that Willy had a black eye. He did not doubt that the Stony Lady would visit them -- with a chaperon, of course -- and he felt that he had the advantage in looks, if only temporarily. He closed his eyes to consider the matter, and when he awoke the cot that Willy had occupied was vacant.

Willy had dressed and carried his blackened eye out into the hard world where explanations of black eyes are laughed at.

But the next day the Stony Lady did come, bringing fruit, of course, which had to be left with the page at the door, but her radiant presence was enough for Wilkins.

"So good of you," he said. "Have you seen Willy?"

"Willy?" she asked. "Oh, yes, the man with the pretty eyes. Yes, he called this morning. Lovely of him, wasn't it."

Wilkins ground his teeth.

"It was like him," he said, viciously. "Nice chap he is to take advantage of my fix."

The Stony Lady stood looking at the other patients, with that loss of words and perfunctory interest that all visitors experience after the first greetings in a hospital -- ready to go but not wishing to seem too eager to leave.

"I've been thinking about what you said in the car," Wilkins began. "About the baby crying for a drink, and all that. We have lots of time to think here, and I've tried to think it out. I guess you're right. In one sense I have acted like a baby. It was babyish to make sport of such a serious thing as --" he hesitated with the universal reluctance of a full-blooded man to say the word "love" and said, "getting married."

"You know how I feel about it, then," said the Stony Lady.

"Yes," he said, "I think I do. I can see that you must think me a baby, in many ways. I have never tried to do anything, or be anything because I never had to. I can see that I am not good enough to deserve you. O, I've thought it all out."

He lay looking at the cracks in the ceiling a while.

"The worst of it," he said, presently with a laugh, "is that I never will deserve you. I haven't got it in me to do big things. We fellows who are born to all this easy life are all babies. We have our toys and we cry for our drink, and that is the whole of our lives."

The Stony Lady looked around uncomfortably.

"Well," she said, "I think I'll run along, now."

"So you see," continued Wilkins, doggedly, "you are quite right to refuse me my drink. Some fellow who needs it ought to have it. I suppose I'll cry for a while -- that is natural -- but I'll get over it before long and play with my other toys, like a good child."

"Do you know," said the Stony Lady, "that you can get a private room here if you want it?"

Wilkins shook his head.

"I don't want it. I could go home, too. But I'm learning things I didn't know, here. It is good for me to see how the real sufferers stand it. See that chap in the third cot from the end? They've got him listed to die next week, and there hasn't been a visitor in to see him for a month, they say. Looks plucky, too, doesn't he?"

She glanced at the man and looked back at Wilkins' serious face, and said a hurried "goodbye." Soon after she left the nurse took Wilkins temperature and the lines on the chart that pictured it formed a peak as high and sharp as Fujiyama.

When the barber come the next morning Wilkins had a shave, and he bought a paper from a boy who sold papers, and sent some oranges across to the "lung man," as he called his vis-a-vis.

He found the day unutterably long, and he was glad when, in the afternoon, the nurses and an attendant began arranging the white screens around the next cot preparatory to its reception of a new inmate. Wilkins hoped the newcomer would be interesting.

Two attendants carried in the stretcher, which hardly bogged under its light load, and disappeared within the screens. Wilkins saw the surgeon enter the enclosure, and heard the short, business-like consultation.

"Run over by a cab on Eighth Avenue. The abdomen badly crushed. Nothing to do but kill the pain. He will die some time tonight." Then there were the usual sounds as the gentle hands of the surgeon did the little that could be done, and the attendant removed the screens, and Wilkins saw upon the pillow of the next cot the yellow curls of a little lad of hardly two years, still under an anesthetic. The nurse glided from the ward and returned with a woman of twenty-eight or so. She was somewhat loudly dressed, but her eyes were red and swollen and she was trying vainly not to sob. She held a wet and crumpled handkerchief against her mouth. She looked at her poor crushed baby, and hiding her face, ran from the room. Wilkins could hear her feet hurrying down the stairs, and her sobs that ended in groans. She was the mother, and she could not bear to look upon him.

He lay a long time studying the face of the boy, and at length saw the eyes open and stare indolently at the glossy ceiling. One arm tossed restlessly on the coverlet and the plaintive, baby voice murmured: --

"Mamma! Dwink!"

The child waited a minute, and then more insistently came the voice again: "Mamma!" and again, "Mamma, please, dwink!"

The little voice was not fretful; it was merely imperative. This was a prince who was accustomed to have his behests obeyed. He waited as long as a prince, the best behaved, could be expected to wait when he had given a command, and then, in the same tone, commanded: --

"Mamma, please, dwink!"

Doubtless he had often called in vain. We cannot give in to all these childish whims, and he closed his eyes and tried to go to sleep, like a good child, but the little hand tossed on the sheet.

When next the child called the gentle, white-capped nurse brought water in a little cup with a spout and wet his lips. She also brushed back the yellow curls with her hand and ran her soft palm across his hot forehead. Wilkins loved her for that. "Little chap seems rather thirsty," he suggested.

The nurse smiled, for Wilkins was handsome, but she would have smiled anyway. It is one of the professional duties.

"Children usually ask for a drink or for their mother," she said. "It is merely habit."

Twilight came, and the ward was made ready for the night. The nurse came again to look at the boy, and brought another pillow that he might be made more comfortable. When she raised him to put it in place he shook his head.

"Boy don't need it," he said sweetly, and then added his request, "Mamma! Dwink!"

The nurse gave him a drink and went out, and the ward was left in semi-darkness.

Wilkins must have gone to sleep, for he had.a sense of being awakened by an unending, annoying repetition of a phrase. As his senses came back to him he recognized the baby's plea. It had become more insistent.

"Mamma! Dwink!" and then, "Mamma, please, dwink," and then, "Mamma, mamma, dwink."

Wilkins never knew how many hundred times the heart-breaking words came from the next cot. He tried to sleep again, but he could not.

"Mamma, please, dwink!"

He could not forget that it was only a baby. Only two years old, and yet, he, thirty, also wept inwardly for something he did not need.

"Mamma, -- please, -- dwink!"

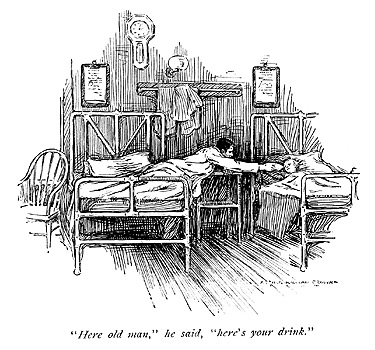

Wilkins sat up. He reached out his hand and felt, on his little iron stand, the cup with the spout, that the nurse had carelessly left there. He bent down and felt of the rope that bound his encased leg to the foot of the bed. It was not, in reality, tied to the bed, but suspended a bucket of sand, that was to keep his leg from shrinking as it healed.

Wilkins edged himself quietly and carefully over in his cot, pulling up the bucket as he did so. By putting his body across the iron table at the bedside he was able to reach the next cot.

"Mamma, dwink, please!"

Wilkins' leg pained frightfully, but he pulled it once more.

"Here, old man," he said, "your drink."

He lifted the cup and held it to the child's lips. But when he raised the cup to pour the water the little hand pushed it aside, impatiently, and the voice called : --

"Mamma, dwink, please!"

Wilkins looked in the cup, and groaned.

"My God!" he cried.

The cup was dry.

How he got back into his cot he never knew, nor did he ever pass a night so long, so cruel. His leg throbbed with pain; his head seemed bursting; and always that plea from the next cot. He hoped the little chap would sleep soon, and about two in the morning the voice did become weaker, and presently stopped altogether.

Wilkins did not sleep, and when daylight came he had the easiest running landau in New York carry him home. It was weeks before he could hobble out on crutches, but his first visit was to the Stony Lady. Willy was there.

"Glad to see you out again old man," he said, cheerfully. "Take this chair; I'm going. Just proposed for the fiftieth and last time and -- I'm going!"

Wilkins took a chair very near the Stony Lady.

"Kate," he said, "I want you to marry me."

"You have told me that before," she said; "Willy has just completed his half century. I thought you had got over that."

Wilkins did not heed her.

"I want you to marry me," he insisted, "I want you. You know I love you."

The Stony Lady smoothed the pattern of her dress across her knee, and ignored his last words. They called for no denial. She did know he loved her.

"Have you forgotten already," she said softly, "what you said in the hospital? Have you forgotten about the baby that cries for a drink that it does not need?"

"No," Wilkins exclaimed. "In forty thousand years I could not forget! I'll admit that I may not need you, or deserve you. If I were a man like the men who do fight, I would not come to you until my deed was done and my fight was fought, but I am a baby, and I must have what I want, and I must have it now."

"You have changed your ideas since I saw you last," she said, gently. "Then you agreed with me."

"Kate," he said, with earnestness, "you were wrong! You should give a baby whatever it cries for. If you were a baby I would give you the whole earth if you wanted it, -- and all I want is heaven. I insist!"

"It is impossible --" she murmured, and his mouth shut and formed a stubborn line, and she looked up quickly and smiled, and added, "to refuse you."