from Leslie's Monthly

Our Neighbor's Children

by Ellis Parker Butler

We who live within the "Fence" consider ourselves a little better than the Oakville persons, who live beyond the "Fence." The "Fence" surrounds a small wood in which our little colony nestles picturesquely, and we live in peace and harmony.

My wife and I make particularly good neighbors. We never quarrel with our fellow dwellers within the "Fence," and they have no reason to quarrel with us, for we have no children. I notice that other people's children cause half the bad feeling in otherwise heavenly suburban villages. Of course, we have mosquitoes, but Providence gives every one something to test the patience. And in the evening, when we hear other people's children complain and fret because the mosquitoes are troublesome, my wife and I, safe within our own screened veranda, thank our stars that we have no children to leave our screen doors ajar.

It is but natural that my wife and I should bear ourselves accordingly. I do not mean that we are uppish about it, but we do feel that we can afford to give better dinners than those who have the expense of children, and if our home is better furnished and our summer journey to the mountains more prolonged, we cannot resist a little honest pride. Many a time when we have had some small pleasure that our neighbors could not afford, the little woman has said to me: "John, you don't know how thankful I am that we have no children," and I have heartily agreed with her.

It is not that we are children haters. Far from it. We are a sane, healthy couple, but when we see the additional worry and trouble that other people's children cause them, we are content to continue as we have lived for the past five years -- our friends still call us "the bride and groom."

I cannot say that we are happier than our fellow dwellers within the "Fence," but we are more carefree. We live joyously.

The other evening, when I returned from the city, my wife met me at our little station, which is just a minute's walk from the "Fence," and when I had tucked her arm under mine I asked her the news of the day. Bobby Jones had cut his finger badly; Estelle Marks had taken the measles; little Tot Hemingway had run away and her mother had gone nearly distracted until the baby was found again; the Wallaces were not going to the mountains this year because Fred had to be sent to a military school in the fall, and they could not afford both. It was the usual daily chapter of children.

As the next day was a holiday I was in unusually high spirits, and the little woman, with true womanly diplomacy, chose the moment when my favorite dish was set before me at dinner to ask a small favor.

"John," she said, quite as if she were opening an ordinary conversation, "did you notice Mrs. Hemingway's reception gown last night?"

"Why, no, dear," I replied. "Was it new?"

"New!" laughed my wife. "The idea! That was just what it was not. I believe she has had that same reception gown ever since we came to the enclosure. It is too bad. She puts everything on those children of hers and has hardly a decent thing of her own. I feel so sorry for her."

"I feel sorry for Hemingway," I said. "The poor old boy is fairly working himself to death. He never comes home until long after dinner, and he told me he felt it his duty to work tomorrow. Children are an expensive luxury."

"That is just what they are!" my wife agreed. "If it were not for the children the Hemingways could live as well as we do, and he wouldn't have to work nights, poor fellow. But John," she added, as if the idea had just occurred to her, "do you remember when the 'Fence' saw its last new reception dress?"

"Why, no -- no," I said. "When was it?"

"Years ago," exclaimed the little woman. "I was figuring it up today, and it was fully two years ago. It's shameful!"

I knew what she was coming to, the sly little lady.

"Positively shameful," I cried; "just on account of those children, too!"

She glanced demurely at her plate.

"Luckily we have no children, John," she said guilefully.

I smiled. I was pleased to see that she was pleased to think she had trapped me.

"I think it is our duty to uphold the honor of the 'Fence' by showing it a new reception gown," I said, and the next moment I had to struggle to prevent her from hugging me into an apoplexy.

All that evening she was strangely quiet and happy. As she sat on the veranda her eyes would wander afar, and I knew she was lost in blissful mazes of bias and gore and pleat and hem. But when we had gone inside for the night, and the shades were down, she threw her arms about my neck again and kissed me.

"Dear, dear old John!" she said, and her eyes were tear-wet. "Just think! A new reception gown!" And even as she said it there filtered into the room the far-off whimpering of the Marks child -- the one with the measles.

"Aren't you glad, dear," my wife asked, "that we haven't any children?" and as I looked down into her happy face, I was heartily glad.

The next day arrived in a glory of fair weather, and we were up almost as early as the sun, for we had planned a jolly day by ourselves -- one of the days that made the "Fence" dwellers call us the "Bride and Groom." We were going to pack a lunch, and wander. She was to take a book, and I my fishing tackle, and beyond that lay a day of happy chances.

"If we had children," she said, "we couldn't go off by ourselves on these long tramps."

We were off while our neighbors of the "Fence" were still at breakfast, and as we passed the Wallace cottage, we ran up to shout a farewell through their breakfast room window, and it was mere chance that we saw the youngest Wallace indolently playing with her stockings five minutes after the breakfast bell had rung. My wife paused just long enough to have one good, long look at the child.

"If all children were like Daisy Wallace," she said, "they would be bearable. She is the most lovable little thing. She has the cutest way of kissing you on the eyelids."

"She seems lazy in the dressing act," I remarked, and I was surprised to see my wife turn on me instantly.

"Why, John Smith!" she cried, "Didn't you ever dawdle over your dressing? When I was a girl, I got oceans of pleasure in being late to breakfast. And what difference does it make when she is just lovely all the rest of the time? I simply love that child. I wonder," she added, wistfully, "if they would let us take her with us today. She would enjoy it so!"

"Nonsense," I said, "we don't want to drag a child along with us all day. Besides, they are going to take her to the photographers today."

We skirted the village, and turned into a country road. The morning air was delightful, and the road quite deserted. We were evidently the only beings abroad, and we stepped out briskly.

"We have the world to ourselves," I said. "We are veritable Monte Cristos of the landscape; monarchs of all we survey."

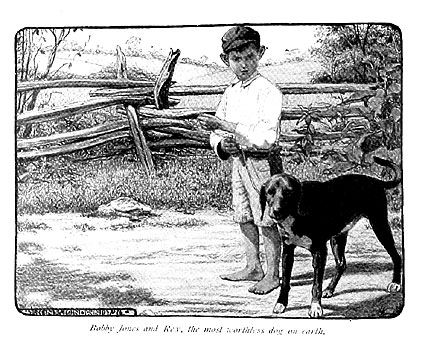

And at a turn of the road we almost fell over Bobby Jones and his inseparable companion, Rex, the most worthless dog on earth.

"Where y' goin'?" he asked.

"Nowhere in particular," my wife assured him.

"So'm I," he said, and then added bravely, "I ain't lost."

"Yes you are, Bobby," I said as severely as I could, "and you had better turn right around and get back home."

He looked at me with wide-eyed surprise.

"Ho!" he said, "You ain't my pa. I don't have to mind you. I won't go home for you."

My wife was bending over him in an instant.

"Bobby!" she said sweetly. "Do you know what your mother is going to have for dinner?"

"No'm," he answered politely.

"I do," said the little woman, "ice cream. And if you get lost you won't get home in time to get any."

Bobby looked at the still unexplored road beyond, and then back at the path he had just traversed. His frown of indecision melted into a smile of anticipation, and taking off his cap he said: --

"Thank you, Mrs. Smith." The little woman laughed joyously. "Oh! your dear child," she cried, and dashed a kiss upon his dusty cheek.

"Nice boy, that," I said.

"Nice!" said my wife. "Is that the best word you can scare up? Why, Bobby is the dearest little chap in the 'Fence.' He and I are great chums. John, I wonder," she said, looking over her shoulder, at the bare legged boy trudging away from us, "if we dare take him with us."

"The ice cream!" I reminded her, and I think she sighed as we started on.

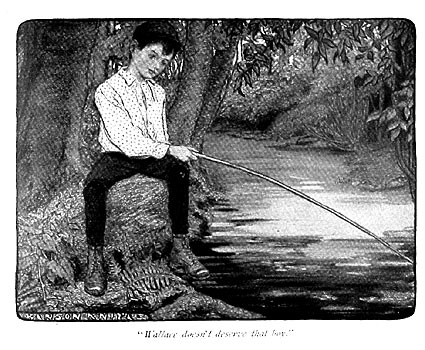

By ten o'clock we had gone far enough from the village, and we pushed our way through a daisy-studded pasture to where a fringe of trees indicated the course of the brook. As I put aside the branches to take my first lingering look at the stream, I paused, and beckoned to the little woman to come quietly.

"Look!" I whispered.

Seated on a stone, as quiet and sedate as ever an ancient fisherman sat, was Ted Wallace. His eyes were glued on his cork, which bobbed on the ripples, and he had thoughts for nothing but the gentle sport of angling. As an enthusiastic angler, my heart went out to the boy. My wife moved slightly, and I put my hand on her arm to command silence.

The boy raised his pole, looked at it critically, and replaced it with a fresh, fat worm. I waited anxiously. Would he? No! But wait -- yes! He bent his head and carefully spat upon the bait. I pressed the little woman's arm. Here was a boy indeed!

I let the branches come together before us and we quietly stole away.

I looked at my elaborate fishing tackle with disgust. What did I know of fishing? What did my fishing excursions amount to but an ineffectual attempt to bring back joys I had when I, too, sat on a log and happy and alone watched my ketsup bottle cork dance on the ripples. But how vain! One cannot go back to those days. There is nothing to do about it. Unless, of course, one could go forward to them in -- well, if one could live again in a boy of his own!

"Wallace doesn't deserve that boy," I said, positively. "What kind of a father is old book-worm Wallace for a boy who likes to fish? I'll bet Wallace never had a fish pole in his hands in his life. Now, I could show Ted a thing or two about fishing. If I had a boy like that --"

"Look!" my wife interposed, "did you ever see anything sweeter?"

At the far end of the pasture Ted's elder sister was straying among the flowers, her sweet face rosy with the fresh air. She was a butterfly among the butterflies, a dainty girl of just the age when a mother's love is strongest and a mother's care the greatest. Asa lover of beauty, I had to admit to myself that there was something about the girl that made one want to own her -- as one would covet and long to preserve a marvelous rose.

"I think Mrs. Wallace hardly appreciates May," said my wife, thoughtfully. "I think she makes her study too much. When I was May's age I would never have thought of taking up a French course in the summer. I spent my time feeding the chickens, and running about the farm and enjoying life. It makes me sad to see the way children are forced nowadays. If I had a girl like that --"

"Yes?" I queried, gently, but the little woman only laughed -- a little recklessly, perhaps.

"What is the use of thinking what I'd do?" she said. "It doesn't make any difference."

We were dog tired when we reached home, and perhaps that was the reason we were more than usually quiet at dinner. I certainly was not cross, but somehow our day had been just a little unsatisfactory, and perhaps the crying of the new baby at the Watkins irritated my nerves. I was glad when we were able to take our chairs to the veranda.

It was a beautiful evening, so still, so calm! The only sounds, aside from the crying of the Watkins' baby, were the light laughter and chatter of the children within the Fence. But I was lonely. I cannot speak for the little woman, but I felt lonely. So I lifted her hand and held it, but still I felt lonely.

There is no time in the twenty-four hours when the Fence is so thoroughly the children's as just at dusk. It is then that our neighbors desert us. There are beginnings of sleepiness among the children, and preparations of little beds by the mothers and for one brief hour my wife and I are as outsiders. We seem to stand outside the Fence and be unable to enter.

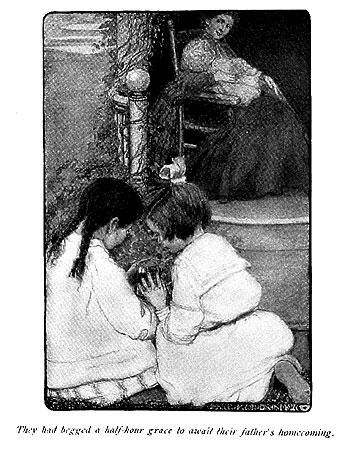

Across the lawn we could see the two Hemingway children, who had begged a half-hour grace to await their father's homecoming before going to bed. Their faces were bent over a tumbler, in which two fireflies were luminous captives, and in the doorway Mrs. Hemingway rocked the sleepy baby.

We heard the train stop, puffing, at the station, and quick steps hurrying along the walk, and then there was a rush and commingling of Hemingway children and father, and the sleepy baby slid from its mother's lap and stood swaying, but eager, with her arms outstretched.

I turned to the little woman, and looked straight at her. Something in her eyes told me that now, if ever, my most seductive wiles were called for.

"Well, little woman," I said so cheerfully that my voice reminded me of a dancing skeleton, "we don't need a lot of kids to bolster up our love, do we?"

Her hand pressed mine lightly in reply.

"And about that gown," I added, gaily, "have you decided on the color yet? I am dying to see you in it. When I think of how you will look, I bless my stars we have no children to deprive me of the sight."

She did not answer and, when I lifted her face, she was weeping!