By Bud Webster

City Slickers, Country Bumpkins, Ants, Robots and Mutants. I Think That's Everybody . . . Oh Yeah, There's Goblins,

to Say Nothing of the Banshee.

It was a place

without a single feature of the space-time matrix that he knew. It was a place

where nothing yet had happened—an utter emptiness. There was neither light nor

dark: there was nothing here but emptiness. There had never been anything in

this place, nor was anything ever intended to occupy this place. —Time is the

Simplest Thing, 1961

Not a word of that reads as though it was written by an old-fashioned,

mid-western newspaperman, but it was. It may not be poetry, exactly, but as

prose it's effective as hell. It's to-the-point without being terse; it paints a

clear, if other-worldly picture; and it sets up the concept of the novel with a

minimum of what my old junior high English teacher used to call "Who shot

John."

Not a word of that reads as though it was written by an old-fashioned,

mid-western newspaperman, but it was. It may not be poetry, exactly, but as

prose it's effective as hell. It's to-the-point without being terse; it paints a

clear, if other-worldly picture; and it sets up the concept of the novel with a

minimum of what my old junior high English teacher used to call "Who shot

John."

So I guess it is the writing of an

old-fashioned, mid-western newspaperman after all: Clifford Simak, to be

exact.

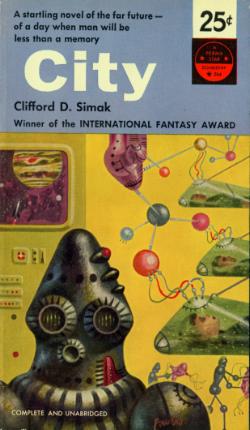

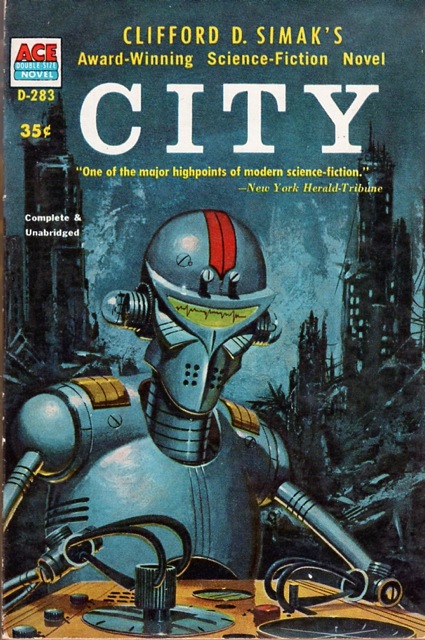

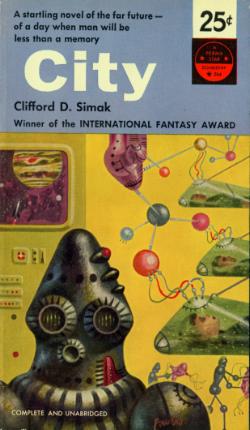

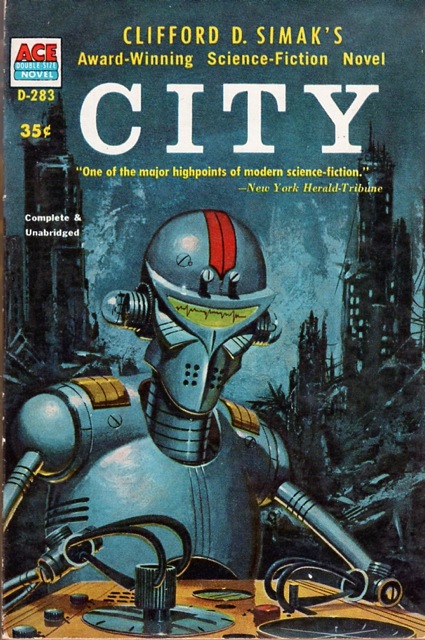

When I was young, oh so much younger than today, I read my first Simak book:

City, in its original Ace edition. I was bowled over—quietly, gently, but bowled over anyway. I had never before

read a story about characters with my name.

That sold me on the book, but the stories paid for themselves. Once I got

over the shock of seeing "Webster" in a book that wasn't about Daniel or Noah, I

leaned forward and began listening to the story Simak was telling me, and I was

hooked.

Here was wonder, but not the thrilling wonder of vast galactic empires,

technological super-science or mile-long spaceships. This was wonder that could

have happened next door to me. You can't imagine how cool that is when you're

twelve. The Universe is impressive as hell, but next door is real.

Simak wasn't all that interested in exploring the Universe, see. What he was

interested in was exploring Man. Not extraordinary men, either, just your

average Joe Lunchpail with everyday problems, like hyper-intelligent mutants and

ants who build their own civilizations. Oh, and talking dogs.

Of

such elements are the stories which comprise the City

sequence made. There's more than that, of course; for all the simplicity of the

prose, Simak's stories aren't at all simple.

Of

such elements are the stories which comprise the City

sequence made. There's more than that, of course; for all the simplicity of the

prose, Simak's stories aren't at all simple.

What they are is bucolic. Where many, if not most, sf authors at the time

concentrated on urban yarns, placed either here or on other planets, Simak took

a page from his youth in small-town Wisconsin and saw the potential for setting

his fantastica among . . . folks. Mountain men, country folk, old-timers, and

farmers, and not a rube or redneck in the lot, except where it served the tale

he was telling. He might include a bumpkin or a village idiot now and then, but

there was a reason for their presence, usually a pivotal one.

It's interesting to compare one pastoral fantasist with another: Ray

Bradbury was also a small-town mid-westerner, another stfnal scrivener whose

stories didn't depend on intricate descriptions of hardware, but it's hard to

imagine two more disparate writers. Although the work of both men seems

deceptively uncomplicated, Bradbury's prose is that of a poet (he did write

poetry extensively, and lovely stuff it is, too); Simak's is, as I indicated

above, journalistic—right down to the lack of contractions. That used to drive

me nuts when I was younger.

So why are they so different, text-wise? Leaving aside the crass and obvious

fact that they're two very different people, there's one detail that might have

had a clear effect. Bradbury's family moved to Los Angeles when he was a young

teenager; Simak stayed in the middle all his life. Of course, that's not the

whole story, not by a long chalk, but it's a salient point nevertheless.

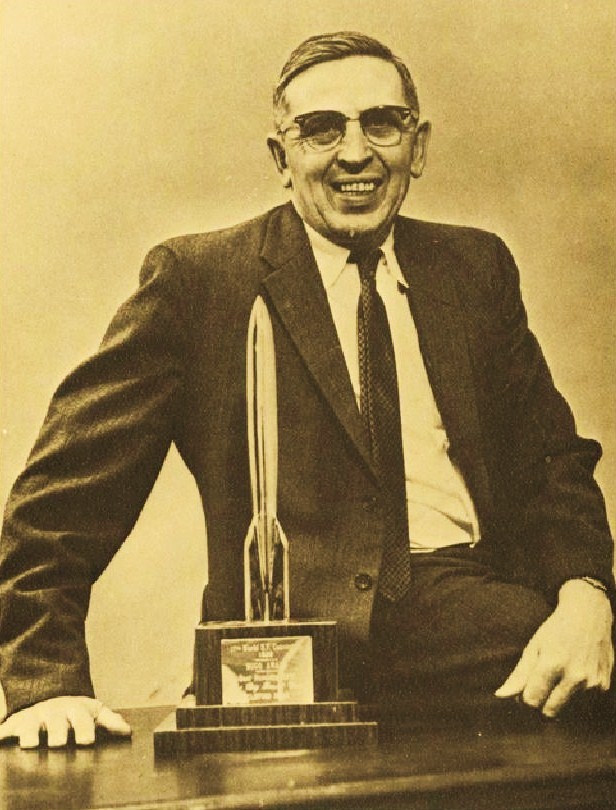

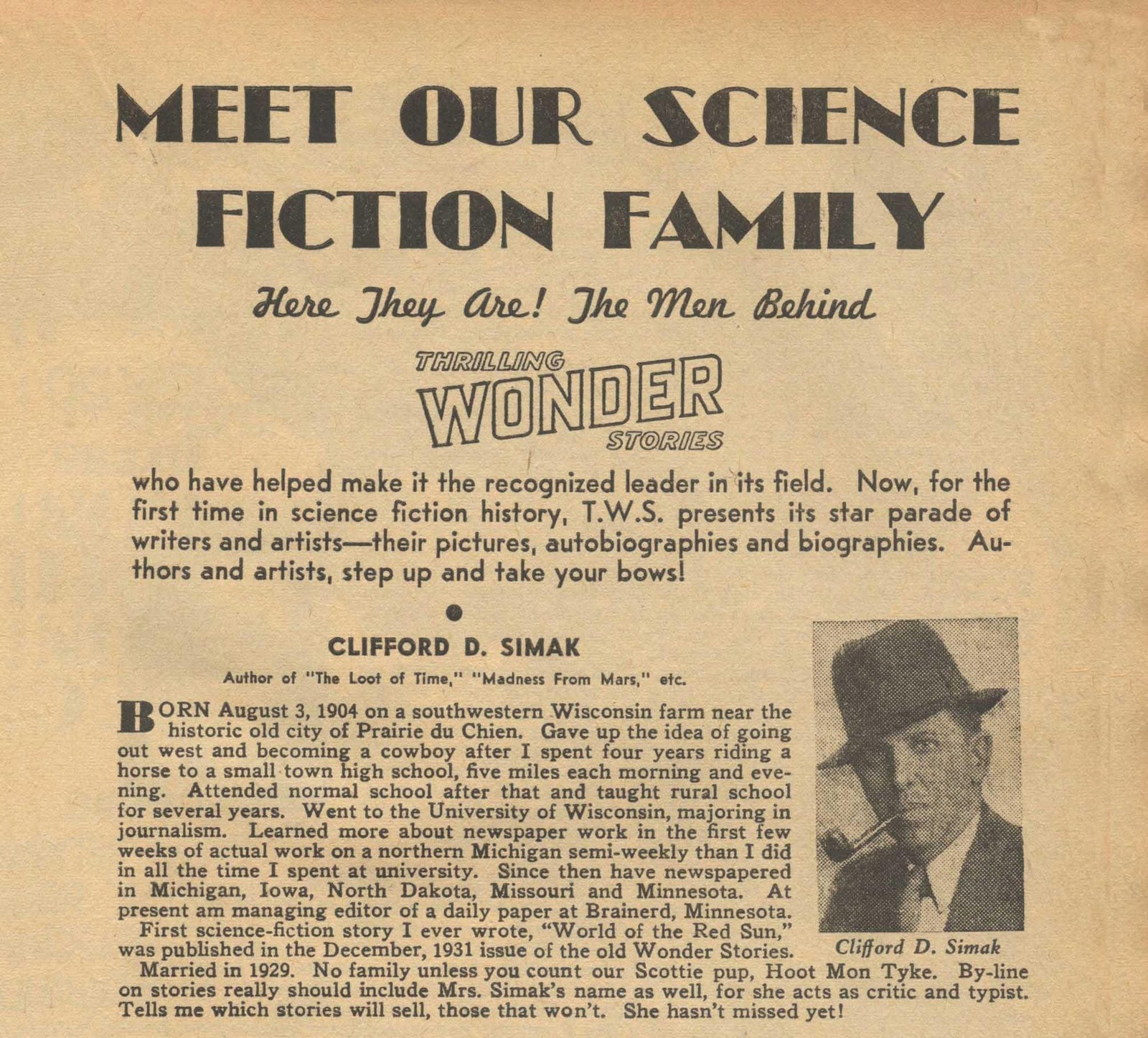

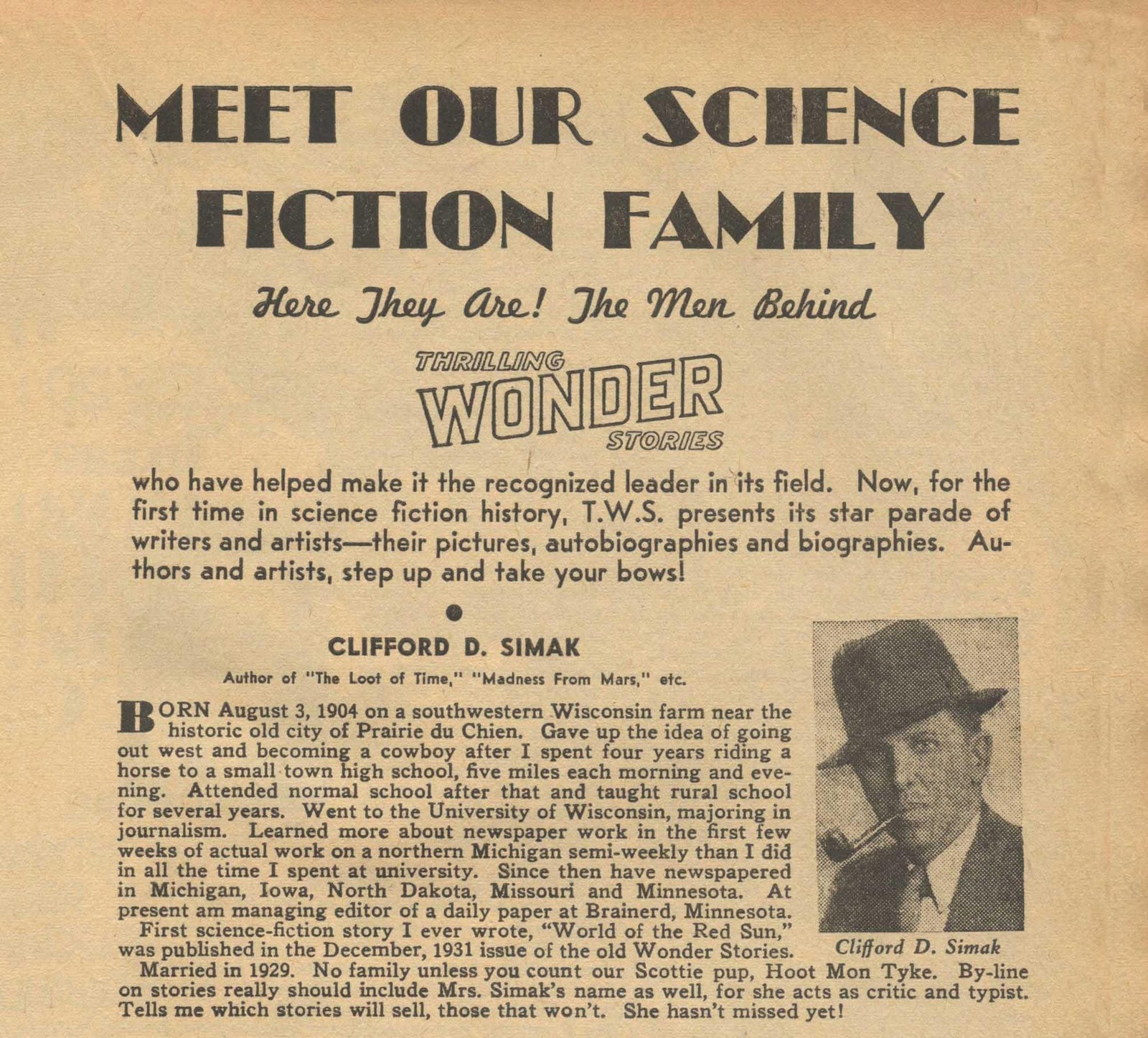

Clifford Donald Simak was born in Millville, Wisconsin in the late

summer of 1904. He matriculated at the Madison campus of the University

of Wisconsin, got married at the age of twenty-five, and at thirty-five

he hooked up with the Minneapolis Star (which later merged with

the Minneapolis Tribune to become The Star-Tribune) ,

where he stayed for the next thirty-seven years until he retired from

the newspaper business. He didn't stop writing, though, just because he

stopped yelling "HOLD THE FRONT PAGE, I GOT A SCOOP!" on a daily

basis. His last novel, Highway of Eternity (Del Rey, 1986) was

published just two years before his death in 1988.

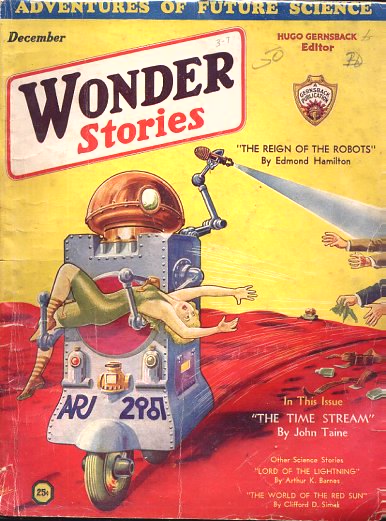

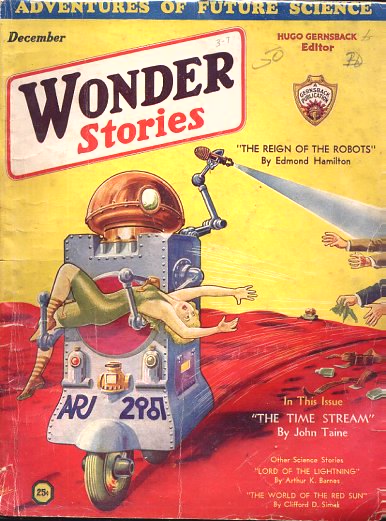

His first story, "The World of the Red Sun," appeared in the December 1931

issue of Wonder Stories (edited by Hugo

Gernsback); Simak not only "sold" the story (Gernsback was notorious for not

paying for stuff unless threatened by a lawsuit, so I'm unsure if he saw a

check), but actually made the cover. That's pretty rare for a newbie.

The story was good enough for Isaac Asimov to reprint in his first Before the Golden Age anthology (Doubleday

1974), and in his head-note has this to say:

During 1931 . . . I began to retell the stories I had

read . . . I well remember sitting at the curb in front of the junior high

school with anywhere from two to ten youngsters listening attentively . . .

[a]nd the specific story that I most vividly recall telling was "The World of

the Red Sun," by Clifford D. Simak . . . .

Considering the radio programs and movies around in the early '30s that

Asimov could have been rapping to his peeps, that's pretty high praise.

Nevertheless, although this story was his first appearance, it was

not the first one accepted. According to Sam Moskowitz in Seekers of

Tomorrow (World Publishing, 1965) Simak's first story, "The Cubes of

Ganymede," was submitted to T. O'Connor Sloane at Amazing. Sloane

kept it for two years before accepting it (without payment); its

subsequent publication was announced in the fan press, but another

three years would pass without the story seeing print before

Sloane ultimately rejected it, citing changes in sf trends. The story

has never been published, and is assumed to be lost.

I looked into this as best I could with all the principals in the ground,

and there's nothing to say that this isn't the gospel truth. Author, editor and

all-around stfnally brilliant guy Robert Silverberg remarked:

Sloane was legendary for his slowness to read and then to publish

and finally to pay for stories. The writers of the Thirties nicknamed

him "T. Oh Come On Slow One." So the Simak tale is probably true . . .

And, of course, once I elicited a quote from the inestimable AgBerg, I find

final confirmation from Simak himself in an interview with the equally

inestimable Darrell Schweitzer published in the February, 1980 Amazing:

I sold my first

story, but it was never published because Amazing sent it back after holding it for

five years and said it was somewhat outdated.

So that, he said as he symbolically wiped the dust off his hands in clichéd

dismissal, would seem to be that. Simak

does sort of indicate above that he was paid, but he may just have been feeling

kind.

Of course, the field is rife with horror stories about editors who hold on

to stories without paying for, publishing or rejecting them, but Sloane was

apparently their patron saint. So my money is on SaM this time around.

Traumatic as hell, and lesser man might have given up the whole thing as a

bad job, never again writing for the vagaries of pulp editors. And, well, Simak

did, at least for a few years. His only appearance between 1932's "The Asteroid

of Gold" (November Wonder Stories) and

1938's "Rule 18" (his second sale to Astounding, for the July issue) was the

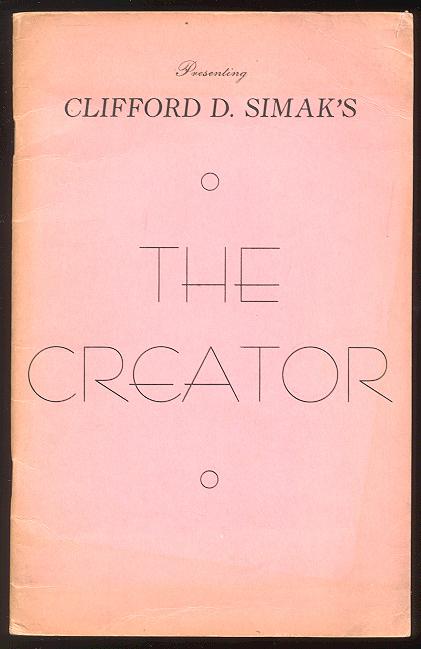

publication of "The Creator," a novelette which ran in the September, 1935 Marvel Tales,[i]

and that may have been sold a good deal earlier.

"The

Creator" was a what-the-hell story, an item that Simak almost certainly intended

as a "so long and thank you very little" gesture. The pulps hadn't been terribly

good to him, let's face it, and by and large they weren't whatcha call yer great

literature. A good deal of what was published by the editors was, frankly,

filler. There might be a couple or three good yarns in any given issue, but a

lot of the rest was cranked out by pro hacks in an afternoon, more or less.

Editors had to fill pages to keep both their readers and their advertisers

happy, and many of them (at the time, anyway) were convinced that their readers

wouldn't know schlock from Shinola if it leapt up and gnawed them on the

fundament.

"The

Creator" was a what-the-hell story, an item that Simak almost certainly intended

as a "so long and thank you very little" gesture. The pulps hadn't been terribly

good to him, let's face it, and by and large they weren't whatcha call yer great

literature. A good deal of what was published by the editors was, frankly,

filler. There might be a couple or three good yarns in any given issue, but a

lot of the rest was cranked out by pro hacks in an afternoon, more or less.

Editors had to fill pages to keep both their readers and their advertisers

happy, and many of them (at the time, anyway) were convinced that their readers

wouldn't know schlock from Shinola if it leapt up and gnawed them on the

fundament.

This wasn't a very heartening prospect for a young and eager wordsmith

determined to be a good writer, and so, secure in the knowledge that he had a

day-job, Simak sat down and pounded out his stfnal fare-thee-well.

Only it didn't end up being that. This was the Thirties, see, and stories

which questioned the very existence of the Judeo-Christian God were, shall we

say, uncommon. It managed to blow a lot of minds (not to mention honking a lot

of people off) even though Crawford's little semi-pro magazine didn't have a

circulation above a few hundred. C'mon, this is a story that states

categorically that the Universe wasn't created by God, but by Some Other Guy. A

really big Some Other Guy, but not the old white man with the long flowing beard

and robes that Michelangelo painted on that ceiling.

The story's influence wasn't just felt among the seated-on-the-subway

readers, but also by a young fan who would make a name for himself (in more than

one way), namely Lester del Rey[ii]. Moskowitz says:

. . . [I]n the

efforts of his relatively more mature years no influence is as evident as that

of Clifford D. Simak, who made an enduring impression on del Rey with "The

Creator" . . . in which the universe is said to be the experiment of a creator

of macrocosmic size rather than the handiwork of God.

No argument; if nothing else, that influence can be seen in one of del Rey's

finest stories, "For I Am a Jealous People!", published in Pohl's Star

Short Novels (Ballantine 1954), a good two decades after the daring

Simak.

You may ask why I'm spending so much time and wordage on what is, after all,

an early short story. There are a couple of reasons, aside from the fact that

despite its place in the Simakian chronology it's still a pretty good read. The

first is what I alluded to above when I called it "his stfnal

fare-thee-well."

When someone creative is waving goodbye to an arena in which they'd hoped to

work, especially after the experience Simak had, the temptation is to pull out

all the stops and write a "Toccata and Fugue in D-Minor" instead of just another

pedestrian prelude. In a very real way, this is what Simak did, throwing caution

to the wind and tackling a subject nobody else had, at least not in the American

pulps. It was so much a "dangerous vision," in fact, that fandom—both organized

and casual—was still arguing about it ten years later. Not a lot, perhaps, but

enough that Crawford was willing to issue that 500-copy chapbook.

The second reason is the clear indication that "The Creator" didn't just

influence Lester Alvarez Et Cetera del Rey; it influenced Clifford Donald Simak

as well. Religion is a theme he would return to a number of times in his career,

always with the interest any good newsman would show an important and absorbing

subject, but without the presumption that he knew The Answer. Frankly, I think

his story-sense would have suffered from a strong commitment one way or the

other, as it would have limited his ability to address more far-ranging

religious concepts. Like our universe having been created by Some Other Guy.

It was also his first book—or, more technically, his first separate

publication. Although it was a very short run, as things go, it was something

other than a cheap pulp copy or tear-sheets for him to hold, and that means

something.

So, why did Simak stay? Why didn't he, as planned, turn his writerly

energies back to covering local/regional news for a large daily? Because

something—and someone—very important happened around the time he was watching

Science Fiction recede in his rear-view: John W. Campbell took over the reins of

Street & Smith's stfnal flagship, Astounding, and all of a sudden not only was

the door opened wider to newer and more controversial[iii]

subject matter, but there was finally a sf pulp editor

who cared how good the stories were as

stories. That's why.

Of course, there had been editors around who wanted good, literate stories

from their writers, and who knew that their readers wouldn't be satisfied with

less. Donald Kennicott of Blue Book,

for one, bought stories from such high-quality authors as Nelson Bond, Philip

Wylie, Booth Tarkington, and some guy named Heinlein; Farnsworth Wright and

Dorothy McIlwraith kept Weird Tales

from descending into a third-rate Terror

Tales; and over on the other side of the Big Drink, the tenures of Newman

Flower and Clarence Winchester at the helm of the UK's Story-Teller

saw the publication of such low-brows as Chesterton, Hodgson, Wells and

Kipling.[iv]

However, periodicals, whether slick or pulp, were never intended to have

permanence; as a rule, even the longer stories the pulpsters wrote ended up in

their readers' trash cans (with a few exceptions, of course). The major houses

flat out refused to believe that there was a market for science fiction between

hard covers, and the mass market paperback was still a decade away. There were a

few collections and anthologies, but book publication was almost the sole

property of the fan-presses (Arkham House, most notably, although there were

others) until the end of WWII.

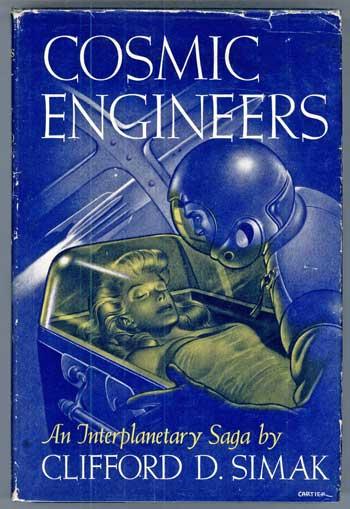

Simak himself didn't see hardcover book publication until Gnome Press

brought out Cosmic Engineers in its

second year, 1950. Originally serialized in Campbell's Astounding

in early 1939, it's . . . well, it's a product of its time, is what it is. Don't

get me wrong, it's perfectly readable even today, but as is the case with a lot

of pulp writing, the dialogue is a bit dated. Not on the level of "Say, what

kind of mug are you, gettin' all sappy over some dame?", perhaps, but dated it

is.

The story itself has echoes of Doc Smith and Edmond Hamilton; it seems that

two universes—one of them ours—are on a collision course, and we have to work

with some of the inhabitants of the other one to avoid said celestial

fender-bender. It's a first novel, no doubt about it, and sentimental as I am

about it, I wouldn't recommend it as a Simakian starting place. However, there

was far better to come, and plenty of it.

Mr. Simak, I

realize that you have done almost everything in newspaper work from printer's

devil to publisher . . . but I know also that you have spent much of the past

half century either on the beat, in the slot, or on the rim—then have gone home

and written highly effective fiction that same day. How

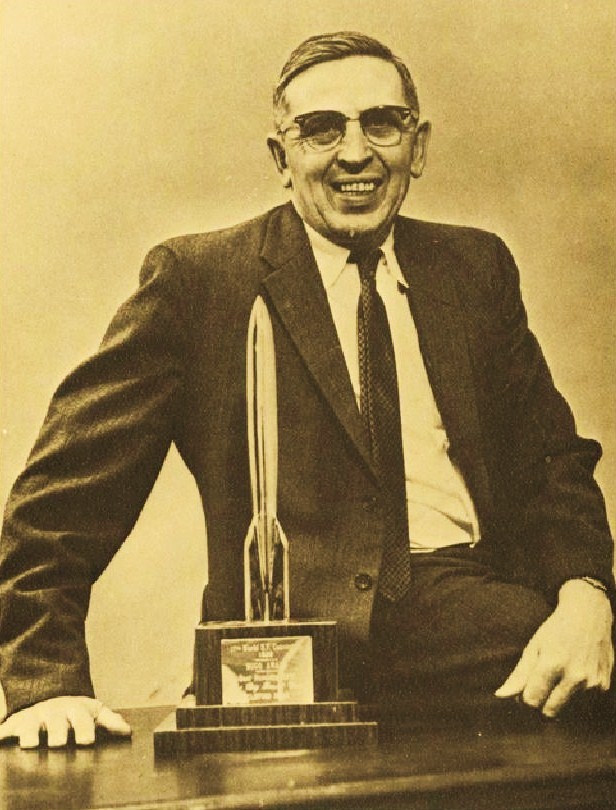

did you do it? —Robert Heinlein, in a letter congratulating Simak on being named

SFWA's 1977 Grand Master

Heinlein goes on to say that the question is rhetorical: ". . . I would be

incapable of understanding the answer and would continue to be amazed."

Simak was the third recipient of SFWA's Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master

Award, following after Jack Williamson in 1976 and Heinlein himself in '75. He

won his share of other awards as well: the 1953 International Fantasy Award for

City; Hugos in 1959 (for his novelette

"The Big Front Yard"), 1964 (for his novel Way

Station), and 1981 (for "Grotto of the Dancing Deer," which incidentally

also won the Nebula, Locus and AnLab Awards for Best Short Story); and three or

four other ones including the Bram Stoker Lifetime Achievement Award in '88

along with Fritz Leiber and Frank Belknap Long.

Think about that for a minute. The Horror Writers of America (HWA), who give

out the Stokers, define the Lifetime award as "Presented periodically to an

individual whose work has substantially influenced the horror genre." Note the

other two recipients that year, Leiber and Long, both fine writers of fantasy,

both dark and not. Simak, though?

Think about that for a minute. The Horror Writers of America (HWA), who give

out the Stokers, define the Lifetime award as "Presented periodically to an

individual whose work has substantially influenced the horror genre." Note the

other two recipients that year, Leiber and Long, both fine writers of fantasy,

both dark and not. Simak, though?

It's not simple, as befits a deceptively intricate writer. Although Simak is

known for his rural characters and settings, there's more there than meets the

stfnal eye. Author, editor and critic Barry Malzberg (who penned the

introduction for the Simak collection Physician to the Universe) says:

Simak had an

odd, tormented streak; try "Second Childhood" . . . from early Galaxy.

Why Call Them Back From Heaven? is a

quasi-zombie novel. Simak is now mislabeled as a gentle pastoralist, the

codgers' farmer in the dell, but take another look.

That's

Simak's rep all right, and in the main it's accurate enough. Look, though, at

just the titles of many of his novels and stories: They

Walked Like Men, The Werewolf

Principle, Cemetery World;

"Hellhounds of the Cosmos," "Bathe Your Bearings in Blood!", "A Death in the

House," "The Thing in the Stone." Any of those could have been titles written by

one of the Lovecraft Circle.

As for the stories themselves, yeah, Simak had his dark side and no mistake.

One of my favorites, an obscure little tale originally published in the March

'41 Astounding as "Masquerade" and

subsequently reprinted by Donald Wollheim as "Operation Mercury" in the Tales of Outer Space side of his only Ace

Double double anthology[v] (if you'll excuse the necessary clumsiness), concerns

two races alien to each other—humans and Mercurians—who would like to find a

basis of cooperation, but can't. There's no great conflict, no hatred, but

neither is there any foundation for friendship. The story, aside from a scene

where the energy-based Mercurians dance wildly to the bluegrass fiddling of a

human crewman called "Old Creepy," is melancholy, almost tragic. It might not

seem so in the colder light of 2011, but seventy years ago this was pretty

dark—especially for ASF[vi].

For that matter, read his 1951 story, "Good Night, Mr. James" (also

published as "Night of the Puudly" in the UK and adapted—badly—as an episode of

The Outer Limits titled "The Duplicate

Man"). This is a profoundly human story, far darker and more layered than

"Masquerade." It involves an illegal clone, a vicious and intelligent alien

called a puudly, and a tragic case of mistaken identity. There's no Yankee

trader ready to take advantage of vacationing out-of-towners here, no

hillbillies, just the quiet devastation of a human life. Twice.

Even the darkness, though, is tinged with compassion. There is a scene in

Goblin Reservation in which the

viewpoint character, Peter Maxwell, makes an unpleasant choice based to a large

degree on practicality, but also out of a sense of the right thing to do, the

Human thing to do. One of the few banshees left in the world is dying, alone and

despised. Out of duty, others are holding a wake, but no one but Maxwell will

simply sit with it as it dies, company in its last moments:

He walked slowly across the intervening

space and stopped a few feet from the tree. The black cloud moved restlessly,

like a cloud of slowly roiling smoke.

"You are the Banshee?" Maxwell asked the

tree.

"You've come too late," the Banshee said, "if you

wish to talk with me."

"I did not come to talk," said Maxwell. "I came to sit with you."

"Sit then," the Banshee said. "It will not be for

long. . . .The others did not come," the Banshee said. "I thought, at first,

they might. For a moment I thought they might forget and come. There need be no

distinction among us now. We stand as one, all beaten to the selfsame level. But

the old conventions are not broken yet. The old-time customs hold."

"I talked with the goblins," Maxwell told him. "They hold a wake for you. The

O'Toole is grieving and drinking to blunt the edge of grief."

"You are not of my people," the Banshee said. "You

intrude upon me. Yet you say you come to sit with me. How does it happen that

you do this?"

Maxwell lied. He could do nothing else. He could not,

he told himself, tell this dying thing he had come for information.

It would have been perfectly easy for Maxwell to pretend to care for this

dying entity, or to reflect its own abhorrence of the human race; it wouldn't

have cared, and nobody else was around to see. But no, despite his primary

reason for being there (read the book to find out, you will not

regret it), he still could not bring himself to effectively slap the

banshee across its face. That might be the human thing to do, but it wouldn't be

Human.

Let me elaborate on that, with your kind indulgence. From a purely practical

standpoint, Maxwell would be justified in asking the dying thing (it's an alien,

not a Terran creature of the fantastic) what it knows about the novel's

Mysteries, including how his Other Self had died. He goes there, in fact, with

that intention in mind and is frustrated by the creature's unwillingness to give

him the answers he needs. No one would have been angry; no one would have blamed

him had he tried to somehow force the banshee to tell him.

He doesn't, though. Instead, he asks the entity if there's anything he can

do to make its passing easier, and as it becomes more talkative, tells it "You

should conserve your strength." There's no badgering, no harrying of the dying

energy-being, not even anger until, with its last "breath," it becomes

recalcitrant and refuses to tell him anything. Instead, he sits with it as any

human might sit with a dying stranger; so that even the most inhuman, unlikeable

life form, one with no emotional connection with (and nothing but a mild

contempt for) Humanity would not have to die alone and ignored.

He doesn't, though. Instead, he asks the entity if there's anything he can

do to make its passing easier, and as it becomes more talkative, tells it "You

should conserve your strength." There's no badgering, no harrying of the dying

energy-being, not even anger until, with its last "breath," it becomes

recalcitrant and refuses to tell him anything. Instead, he sits with it as any

human might sit with a dying stranger; so that even the most inhuman, unlikeable

life form, one with no emotional connection with (and nothing but a mild

contempt for) Humanity would not have to die alone and ignored.

That simple gesture of compassion is a touchstone of Simak's perception of

what Mankind means, and the scene one of his most eloquent expressions of how a

good man responds to the Darkness surrounding him.

You know something? I'm almost 4000 words into a column that generally runs

no more than 2200, and I am nowhere near being done talking about this writer.

Not only that, but I have another seven pages of bibliography to present you.

You guys know me by now, and you know I can wax as loquacious as the next

guy (assuming the next guy is as long-winded as I am), but Simak (not pronounced

"SY-mak" as I said it as a kid, or even "Sih-mak" as I have since then, but

"SIH-mik") was quite a significant influence on my own fiction, and I've read

and enjoyed almost all of his books and stories. I hope I can pass along at

least some of my enthusiasm to you, the readers, but in any case please bear

with me; I'll take a look at a couple more of my favorites and then return you

to your regular pursuits.

****

A million years ago there had been no river

here and in a million years to come there might be no river—but in a million

years from now there would be, if not Man, at least a caring thing. And that was

the secret of the universe, Enoch told himself—a thing that went on caring.

(From Way Station)

Not many writers are capable of summing up Humanity and its place in the

cosmos. Many try throughout their careers to do so, devoting reams of paper to

the task, always falling short. Poets, novelists, playwrights, essayists; all

have done their level best to define the Human Condition, seeking and creating

complexities, looking in the darkest corners of their souls to find the one

identifying characteristic that separates Man from, say, Plant.

Clifford Simak did it in fewer than sixty words. That's

what.

Way Station is Simak at his best,

combining that pastoral gentility he's so well known for with a subtle, but

deep-rooted melancholia that makes Ray Bradbury look a little like Ohio

Express[vii] lyrics.

Enoch Wallace didn't die in the War Between the States. Instead, he was

chosen by aliens to tend the Terran depot of an intergalactic transport system,

which has remained hidden from prying Terran eyes until now, when the Gummint

notices that he's still, y'know, alive, which makes them curious. This is made

worse when the body of an alien is disinterred by a Gummint man. There were

already plenty of questions being asked—you can't be 100+ years old and not

attract some attention—and things get a little uncomfortable.

Enoch Wallace didn't die in the War Between the States. Instead, he was

chosen by aliens to tend the Terran depot of an intergalactic transport system,

which has remained hidden from prying Terran eyes until now, when the Gummint

notices that he's still, y'know, alive, which makes them curious. This is made

worse when the body of an alien is disinterred by a Gummint man. There were

already plenty of questions being asked—you can't be 100+ years old and not

attract some attention—and things get a little uncomfortable.

Wallace is something of a loner, as are many of Simak's people. Not

entirely, but since he's more than a century old, that kinda precludes his

palling around with the local bowling team. He does have some "human"

companions, but are they ghosts? They may as well be, but actually they're

projections of long-dead friends who eventually leave him. The locals are more

protective of him than suspicious, but his loneliness is a necessary adjunct of

his "job." His best friend, in fact, is Ulysses, the alien who recruited him to

begin with. There is a girl though; mute, deaf, and possessed of certain . . .

talents, she is the only one of her redneck family who wouldn't sell the other

members for a jug o' moonshine.

The crisis (all good stories have some kind of crisis, or they ain't

stories) comes when Wallace, an intelligent man with access to other-worldly

science, determines irrefutably that Earth is headed for an unavoidable atomic

conflagration. The ultimate outcome is . . . but no, that would be telling.

Artificial longevity, aliens, intergalactic teleportation, and there's even

some virtual reality (a la Bradbury's "The Veldt") as well. Those are the

science fictional elements, and most any of Simak's contemporaries could have

woven a pretty good yarn from them. Hell, Asimov alone could have kicked it out

of the park.

Trouble is that Asimov, however erudite and visionary, had a tendency to

create thin, almost wooden characters. In a very real way, his people were

there to handle the hardware, to hold it up in front of the reader and (in

effect) say, "See? Isn't this cool?"?

Simak was never satisfied with just the technology. For him, that meant nothing

without the human component. He was a rara avis in the world of Science Fiction, at

least for his time—an author for whom Character was just as important as Idea.

There are lots and lots of ideas out there to be marveled at, believe me: time

dilation and relativity, artificial intelligence, alien-human compatibility,

magic rings/swords/books, smart-alecky kids who do wizardry, and so on.

Good fiction, though, demands a story not just about hardware or weird

beasties but how those concepts affect—and are affected by—humans. Just plain

folks. That's what Simak excelled at. Don't get me wrong; you can't take the

fantastical element out of his stories without losing the humanity, too.Way Station would fall apart without the

artificial longevity, aliens, intergalactic teleportation and so on against

which Simak cast his characters, no doubt about it, but at the same time without

the people there would be little for the hardware to do.

This really is rarer than you might think. There are plenty of sf writers

who are, as we say, idea driven, and more than a few who are character driven.

Those who can do both at the same time, seamlessly, are exceptional. Simak leads

that pack, in mine own (not-so-) humble opinion.

There's more to it, although for almost anyone else that would be plenty.

Simak's stories, long- or short-form, are laced with wit. Not just humor, for

all that there's plenty of it to be found (there's something really comical, if

slightly surreal, about Mercurian energy beings frenetically square-dancing to

Old Creepy's fiddlin'), but wit; i.e.,

skill at engaging the reader and giving his characters depth and breadth. He

doesn't resort to giving them funny hats like so many others do, but instead

creates richness and intensity that elevates him away from the level of mere

pulp.

In Goblin Reservation (Putnam

1968), for example, he gives us a well-educated Neanderthal named Alley-Oop,

alien bad guys who run around on wheels instead of feet, an android saber-tooth,

William Shakespeare in the flesh, and a ghost (just called Ghost) with whom the

late playwright pals around. Ghost knows he's a ghost, but doesn't remember just

whom he is a ghost of. You get the idea. Well into the story, Ghost suddenly

recalls that he is the spirit of . . . Willy the Shake, himself. Both of them

are more than a little freaked out, understandably, and take off running and

screaming.

It's not over yet, however. During the magnificent dénouement

of this wonder-filled book, when superb chaos reigns and the truly magical egg

is hatching, we see Shakespeare and his own ghost, reconciled and again friends,

dancing together in a moment of pure enchantment. My god, what a book

this is.

****

[W]hat I recall is meeting Cliff Simak [at

Chicon II, the 1952 world convention] . . . There, sitting with him in a Chicago

hotel room, sipping a little good whiskey and talking about ourselves and our

worlds, I really got to know and love him. The writers of good science fiction

are nearly always bright and interesting and likable, but Cliff has a genuine

humanity, something calmly wise and warm that is all his own.

No less a stfnal personage than Jack Williamson wrote that about our subject

in his memoir, Wonder's Child: My Life in

Science Fiction (Bluejay 1984), and I think it sums up Simak's gift

elegantly. "Calmly wise and warm" isn't just a richly-deserved paean but a goal,

a challenge.

From a personal perspective, I can cite Clifford D. Simak as a major

influence on my own writing. Without "The Big Front Yard" and "Idiot's Crusade"

(among others) there would be no Gentleman Mechanic from Central Garage,

Virginia, no hobos in space, and precious little else of a fictional nature from

Yours Truly. One of the great disappointments of my life is that I was never

able to find a copy of the first edition of City (which is, after all, a history of the

Webster family) for him to sign.

Still, the legacy he left for me and countless other reader/writers in the

field is for all practical purposes incalculable. One of the greatest

compliments I've ever been paid as a bookseller was when a young college-aged

customer returned to my table this past year at a local convention and said,

"Last year you suggested I buy Way

Station. I'll buy anything else you suggest." I take only a small part of

the credit for that, much as it made me beam for a couple of hours. The calmly

wise and warm Clifford Simak deserves it all. I'll give the last word to a

critic and commentator far more articulate than I, Barry Malzberg, himself a

humanist of great warmth and skill:

Simak's work is already buried, but he knew

that was inevitable and all of it is informed by wonder in the face of oblivion.

What a great writer and more importantly: what a good man.

[i] William

Crawford, the editor of Marvel Tales,

would reprint the story as a 500-copy chapbook in 1946. It would see another

chapbook publication 35 years later when Simak was the guest of honor at the

39th World Science Fiction Convention in Denver, with appreciations

by Heinlein, Asimov, Williamson and Pohl added.

[ii] For

years, del Rey claimed that his name was "Ramon Felipe San Juan Mario Silvio

Enrico Smith Harcourt-Brace Sierra y Alvarez del Rey y de los Uerdes" or some

combination of the foregoing. His real name was, in fact, Leonard Knapp. Why did

he insist on that long string, or even the short-form? The quick answer is

"Wouldn't you?", but the reality has more to do with a young man's desire to

stand out from all the other faans, a desire I can fully understand and with

which I can certainly sympathize.

[iii]

Leaving aside sexuality, of course, and allow me to dispel a myth of very long

standing. It turns out that no matter how much Campbell may have blamed his

assistant, Kay Tarrant, for his refusal to allow hubba-hubba references in Astounding, it has become clear that it was

Campbell himself who was the "prude" and not Ms. Tarrant. That she was willing

to accept the blame for his own puritanical predilections is an indication of

how much respect and affection she had for the old (non)goat.

[iv] I've

never cared much for Kipling, but to be honest I've never really Kippled that

much. HAH! Oh, come on, you had to know I was going there.

[v] D-73,

to be exact; the other side was Adventures in

the Far Future. I've written about this little gem in detail in my

"D-73—A (Sp)Ace Oddity" column, which is reprinted in the collection of those

columns, Anthopology 101: Reflections,

Inspections and Dissections of SF Anthologies, available from The Merry

Blacksmith Press. Just so you'll know. Ahem.

[vi] Not all Astounding stories are upbeat

adventures about human smart/tough-guys outsmarting hide-bound aliens, much as

many people (including myself) tend to believe so. Campbell responded to

darkness as well, as he proved only too well with Tom Godwin's "The Cold

Equations" among others. A good story is a good story, regardless of tone.

[vii] They

recorded "Yummy, Yummy, Yummy" back in 1968, the same year Frank Zappa released

his Sgt. Pepper parody, We're Only In It for

the Money. Rock 'n' roll is funny.

(As usual, the bibliography below is as

complete as I can make it, and I welcome additions and corrections. For Novels

and Collections, "hc" designates hardcover and "pb", paperback. UK editions

are listed in a similar fashion. My thanks to Phil Stephensen-Payne and Scott

Henderson for their expert help in compiling this monster.)

Short Stories

- "The World of the Red Sun"—December 1931 Wonder Stories

- "The Voice in the Void"—Spring 1932 Wonder Stories Quarterly

- "Mutiny on Mercury"—March 1932 Wonder Stories

- "Hellhounds of the Cosmos"—June 1932 Astounding Stories

- "The Asteroid of Gold"—November 1932 Wonder Stories

- "The Creator"—March/April 1935 Marvel Tales (Volume 1, #4)

- "Rule 18"—July 1938 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "Hunger Death"—October 1938 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "Reunion on Ganymede"—November 1938 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "The Loot of Time"—December 1938 Thrilling Wonder Stories (Plagiarized as "S.O.S in Time" by Australian "writer"

Durham Keith Garton under the pseudonym "Durham Keys" in the October 1950 issue of the Australian magazine, Thrills Incorporated.)

- "Cosmic Engineers"—serial, February-March-April 1939 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "Madness from Mars"—April 1939 Thrilling Wonder Stories

- "Hermit of Mars"—June 1939 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "The Space-Beasts"—April 1940 Astonishing Science Fiction

- "Rim of the Deep"—May 1940 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "Clerical Error"—August 1940 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "Sunspot Purge"—November 1940 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "Masquerade"—March 1941 Astounding Science-Fiction (AKA "Operation Mercury")

- "Earth for Inspiration"—April 1941 Thrilling Wonder Stories

- "Spaceship in a Flask"—July 1941 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "The Street That Wasn't There"—w/Carl Jacobi, July 1941 Comet (AKA "The Lost Street")

- "Tools"—July 1942 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "A Bomb for No. 10 Downing"—September 1942 Sky Fighters (non-sf)

- "Shadow of Life"—March 1943 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "A Hero Must Not Die"—June 1943 Sky Raiders (non-sf)

- "Hunch"—July 1943 Astounding Science-Fiction

- "Infiltration"—July 1943 Science Fiction Stories

- "Green Flight, Out!"—Fall 1943 Army-Navy Flying Stories (non-sf)

- "Guns on Guadalcanal"—Fall 1943 Air War (non-sf)

- "Message from Mars"—Fall 1943 Planet Stories

- "Ogre"—January 1944 Astounding Science Fiction

- "Lobby"—April 1944 Astounding Science Fiction

- "Smoke Killer"—May 1944 Lariat Story Magazine (non-sf)

- "City"—May 1944 Astounding Science Fiction

- "Mr. Meek—Musketeer"—Summer 1944 Planet Stories

- "Cactus Colts"—July 1944 Lariat Story Magazine (non-sf)

- "Huddling Place"—July 1944 Astounding Science Fiction (Chosen by SFWA for The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Vol. 1)

- "Mr. Meek Plays Polo"—Fall 1944 Planet Stories

- "Trail City's Hot-Lead Crusaders"—September 1944 New Western (non-sf)

- "Census"—September 1944 Astounding Science Fiction

- "The Gravestone Rebels Ride by Night!"—October 1944 Big Book Western Magazine (non-sf)

- "War is Personal"—Winter 1945 Army-Navy Flying Stories (non-sf)

- "Desertion"—November 1944 Astounding Science Fiction

- "The Fighting Doc of Bushwack Basin"—November 1944 .44 Western Magazine (non-sf)

- "The Reformation of Hangman's Gulch"—December 1944 Big Book Western Magazine (non-sf)

- "Way for the Hangtown Rebel!"—May 1945 Ace High Western Stories (non-sf)

- "Good Nesters are Dead Nesters"—July 1945 .44 Western Magazine (non-sf)

- "The Hangnoose Army Rides to Town"—September 1945 Ace High (non-sf)

- "Barb Wire Brings Bullets"—November 1945 Ace High Western Stories (non-sf)

- "The Gunsmoke Drummer Sells a War"—January 1946 Ace High Western Stories (non-sf)

- "No More Hides and Tallow"—March 1946 Lariat Stories (non-sf)

- "When it's Hangnoose Time in Hell"—April 1946 .44 Western Magazine (non-sf)

- "Paradise"—June 1946 Astounding Science Fiction

- "Hobbies"—November 1946 Astounding Science Fiction

- "Aesop"—December 1947 Astounding Science Fiction

- "Eternity Lost"—July 1949 Astounding Science Fiction

- "Limiting Factor" - November 1949 Startling Stories

- "The Call from Beyond"—May 1950 Super Science Stories

- "Seven Came Back"—October 1950 Amazing Stories (AKA "Mirage")

- "Time Quarry"—serial, October-November-December 1950 Galaxy Science Fiction

(Title was changed to Time and Again when published as a novel)

- "Bathe Your Bearings in Blood!"—December 1950 Amazing Stories (AKA "Skirmish")

- "The Trouble with Ants"—January 1951 Fantastic Adventures (AKA "The Simple Way")

- "Second Childhood"—February 1951 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Good Night, Mr. James"—March 1951 Galaxy Science Fiction (AKA "The Duplicate Man" and "The Night of the Puudly"[UK only])

- "You'll Never Go Home Again"—July 1951 Fantastic Adventures (AKA "Beachhead")

- "Courtesy"—August 1951 Astounding Science Fiction

- "The Fence"—September 1952 Space Science Fiction

- "Gunsmoke Interlude"—October 1952 Ten Story Western (non-sf)

- "Ring Around the Sun"—serial, December 1952-January-February 1953 Galaxy Science Fiction

- " . . . And The Truth Shall Make You Free"—March 1953 Future Science Fiction (AKA "The Answers")

- "Retrograde Evolution"—April 1953 Science Fiction Plus

- "Junkyard"—May 1953 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Kindergarten"—July 1953 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Spacebred Generations"—August 1953 Science Fiction Plus (AKA "Target Generation")

- "The Questing of Foster Adams"—August/September 1953 Fantastic Universe

- "Worrywart"—September 1953 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Shadow Show"—November 1953 Fantasy & Science Fiction

- "Contraption"—inStar Science Fiction Stories, ed. Frederik Pohl, Ballantine 16, 1953

- "Immigrant"—March 1954 Astounding Science Fiction

- "Neighbor"—June 1954 Astounding Science Fiction

- "Green Thumb"—July 1954 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Dusty Zebra"—September 1954 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Idiot's Crusade"—October 1954 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "How-2"—November 1954 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Project Mastodon"—March 1955 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Full Cycle"—November 1955 Science Fiction Stories

- "The Spaceman's Van Gogh"—March 1956 Science Fiction Stories

- "Drop Dead"—July 1956 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "So Bright the Vision"—August 1956 Fantastic Universe

- "Honorable Opponent"—August 1956 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Galactic Chest"—September 1956 Science Fiction Stories

- "Jackpot"—October 1956 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Worlds Without End"—Winter 1956/57 Future (#31)

- "Operation Stinky"—April 1957 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Founding Father"—May 1957 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Lulu"—June 1957 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Shadow World"—September 1957 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Death Scene"—October 1957 Infinity Science Fiction

- "Carbon Copy"—December 1957 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Nine Lives"—December 1957 Short Stories

- "The World That Couldn't Be"—January 1958 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Leg. Forst."—April 1958 Infinity Science Fiction

- "The Sitters"—April 1958 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "The Money Tree"—July 1958 Venture Science Fiction

- "The Civilization Game"—November 1958 Galaxy Magazine

- "The Big Front Yard"—October 1958 Astounding Science Fiction

(Winner, 1959 Hugo award for best novelette, and chosen by SFWA for The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Vol. 2b)

- "Installment Plan"—February 1959 Galaxy Magazine

- "No Life of Their Own"—August 1959 Galaxy Magazine

- "A Death in the House"—October 1959 Galaxy Magazine

- "Final Gentleman"—January 1960 Fantasy & Science Fiction

- "Crying Jag"—February 1960 Galaxy Magazine

- "All the Traps of Earth"—March 1960 Fantasy & Science Fiction

- "Gleaners"—March 1960 If

- "Condition of Employment"—April 1960 Galaxy Magazine

- "The Golden Bugs"—June 1960 Fantasy & Science Fiction

- "The Trouble with Tycho"— October 1960 Amazing

- "Shotgun Cure"—January 1961 Fantasy & Science Fiction

- "Horrible Example"—March 1961 Analog Science Fact-Fiction

- "The Fisherman"—serial, April-May-June-July 1961 Analog Science Fact-Fiction

(Title was changed to Time is the Simplest Thing when published as a novel)

- "The Shipshape Miracle"—January 1963 If

- "Day of Truce"—February 1963 Galaxy Magazine

- "Physician to the Universe"—March 1963 Fantastic Science Fiction

- "A Pipeline to Destiny"—HKLPLOD #4, Summer 1963 (unfinished story in a fanzine published by Michael McInerney)

- "Here Gather the Stars"—serial, June-August 1963 Galaxy Magazine

(Title was changed to Way Station when published as a novel)

- "New Folk's Home"—July 1963 Analog Science Fact-Fiction

- "Over the River and Through the Woods"—May 1965 Amazing Stories

- "Small Deer"—October 1965 Galaxy Magazine

- "The Goblin Reservation"—serial, April-June 1968 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "Buckets of Diamonds"—April 1969 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "I Am Crying All Inside"—August 1969 Galaxy Science Fiction

- "The Thing in the Stone"—March 1970 If

- "Reality Doll"—Spring 1971 Worlds of Fantasy (was expanded to novel length as Destiny Doll)

- "The Autumn Land"—October 1971 Fantasy & Science Fiction

- "To Walk a City's Street"—in Infinity #3, ed. Robert Hoskins, Lancer 1972

- "The Observer"—May 1972 Analog Science Fiction-Science Fact

- "Cemetery World"—serial, November-December 1972-January 1973 Analog Science Fiction-Science Fact

- "Construction Shack"—January/February 1973 Worlds of If

- "Our Children's Children"—serial, May/June-July/August 1973 Worlds of If

- "Epilog"—in Astounding, ed. Harry Harrison, Random House 1973

- "UNIVAC: 2200"—in Frontiers 1: Tomorrow's Alternatives, ed. Roger Elwood, MacMillan 1973

- "The Marathon Photograph"—in Threads of Time, ed. Robert Silverberg, Thomas Nelson 1974

- "The Birch Clump Cylinder"—in Stellar #1, ed. Judy-Lynn del Rey, Ballantine/DelRey 1974

- "The Ghost of a Model T"—in Epoch, ed. Roger Elwood and Robert Silverberg, Berkley 1975

- "Senior Citizen"—October 1975 Fantasy & Science Fiction

- "Unsilent Spring"—(w/Richard Simak) in Stellar #2, ed. Judy-Lynn del Rey, Ballantine 1976

- "Auk House"—in Stellar #3, ed. Judy-Lynn del Rey, Ballantine/Del Rey 1977

- "Brother"—October 1977 Fantasy & Science Fiction

- "Party Line"—November/December 1978 Destinies

- "The Visitors"—serial, October-November-December 1979 Analog Science Fiction-Science Fact

- "Grotto of the Dancing Deer"—April 1980 Analog Science Fiction-Science Fact

(Winner, 1981 Hugo, Nebula, Analytical Laboratory and Locus awards)

- "The Whistling Well"—in Dark Forces, ed. Kirby McCauley, Viking 1980

- "Byte Your Tongue!"—in Stellar #6, ed. Judy-Lynn del Rey, Ballantine 1981

Novels

- The Creator—originally in March/April 1935 Marvel Tales;

first separate publication was as a chapbook in 1946 by William Crawford, and reprinted again in September 1981 by Locus Press

- Cosmic Engineers—Gnome Press, 1950 (hc); Paperback Library 52-506, 1964 (pb)

- Empire—Galaxy Novel #7, 1951 (digest-sized); something of an oddity in that Simak wrote the book based

on an unpublished novel by a teen-aged John W. Campbell. In Clifford D. Simak: A Primary and Secondary Bibliography

(G. K. Hall, 1980), compiler Muriel Becker quotes Simak: "Empire was essentially a rewrite of John's plot. I may have

taken a few of the ideas and action, but I didn't use any of his words. And I certainly tried to humanize his characters."

It was ultimately rejected by Campbell for Astounding for unknown reasons.

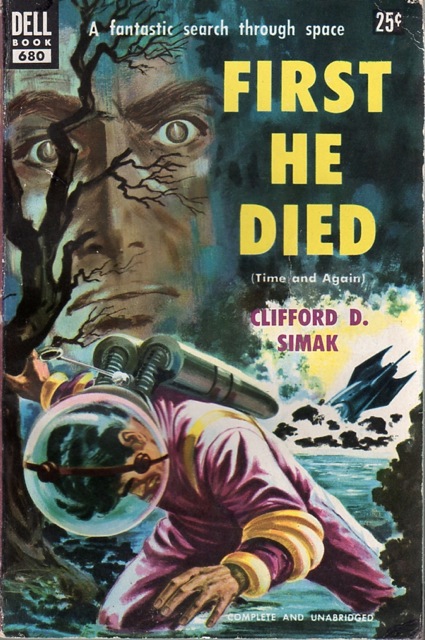

- Time and Again—Simon & Schuster, 1951 (hc); Dell 680, 1953 as First He Died (pb,

originally serialized as "Time Quarry" with a variant ending)

- City—Gnome Press, 1952 (hc); Perma Book 264 (pb) "Epilog" added to the 1981 Ace reprint

(Winner, 1953 International Fantasy Award for best fiction book)

- Ring Around the Sun—Simon & Schuster, 1953 (hc); Ace Double D-61, 1954

(pb, bound with L. Sprague de Camp's Cosmic Manhunt)

- Time is the Simplest Thing—Doubleday, 1961 (hc); Fawcett Crest D-547 (pb, originally serialized as "The Fisherman")

- The Trouble With Tycho—Ace Double D-517, 1961 (pb, bound with A. Bertram Chandler's Bring Back Yesterday)

- They Walked Like Men—Doubleday, 1962 (hc); MacFadden 50-184, 1963 (pb)

- Way Station—Doubleday, 1963 (hc); MacFadden 50-198 (pb, Winner, 1964 Hugo award for best novel)

- All Flesh Is Grass—Doubleday, 1965 (hc); Berkley Medallion X1312, 1966 (pb)

- Why Call them Back From Heaven?—Doubleday, 1967 (hc); Ace H-42, 1968 (pb, Ace Science Fiction Special #1)

- The Werewolf Principle—Putnam, 1967 (hc); Berkley Medallion S1463, 1968 (pb)

- The Goblin Reservation—Putnam, 1968 (hc); Berkley Medallion S1671, 1969 (pb,

Winner, 1968 Galaxy Award, the first and only Galaxy readers' choice award)

- Out of Their Minds—Putnam, 1970 (hc); Berkley Medallion 1970 (pb)

- Destiny Doll—Putnam, 1971 (hc); Berkley Medallion, 1972 (pb)

- A Choice of Gods—Putnam, 1972 (hc); Berkley Medallion 1973 (pb)

- Cemetery World—Putnam, 1973 (hc); Berkley Medallion 1974 (pb, The 1983 DAW edition restores Simak's preferred text)

- Our Children's Children—Putnam, 1974 (hc); Berkley Medallion 1975 (pb)

- Enchanted Pilgrimage—Berkley/Putnam, 1975 (hc); Berkley Medallion, 1975 (pb)

- Shakespeare's Planet—Berkley/Putnam, 1976 (hc); Berkley Medallion, 1977 (pb)

- A Heritage of Stars—Berkley/Putnam, 1977 (hc); Berkley 1978 (pb,

Winner, 1978 Jupiter Award for best novel)

- The Fellowship of the Talisman—Ballantine/Del Rey, 1978 (hc); Del Rey 1979 (pb)

- Mastodonia—Ballantine/Del Rey, 1978 (hc, also published as Catface by Sidgwick & Jackson

in the UK the same year. Significantly expanded and re-written version of the short story, "Project Mastodon,"

originally in the March, 1955 Galaxy)

- The Visitors—Ballantine/Del Rey, 1980 (hc)

- Project Pope—Ballantine/Del Rey, 1981 (hc)

- Special Deliverance—Ballantine/Del Rey, 1982 (hc)

- Where the Evil Dwells—Ballantine/Del Rey, 1982 (hc)

- Highway of Eternity—Ballantine/Del Rey, 1986 (hc)

- Spacebred Generations—Wildside, 2009 (Book publication of the 1953 short-story)

Collections

- Strangers in the Universe—Simon & Schuster, 1956 (hc); Berkley G-71, 1957

(pb, first edition collects eleven stories; paperback collects seven)

- The Worlds of Clifford Simak—Simon & Schuster, 1960 (hc); Avon G-1096, 1961 (pb);

also published in the UK by Faber and Faber as Aliens for Neighbours that same year.

First edition collects twelve stories; US paperback collects six; Faber and Faber edition collects nine.

In 1962, Avon published G-1124, Other Worlds of Clifford Simak, which collects the other six stories from the first edition.)

- All the Traps of Earth and Other Stories—Doubleday, 1962 (hc); Macfadden, 1963 (pb).

Bibliographically, this book is complicated. The first edition collects nine stories, the 1963 paperback collects six;

in the UK, the book was split into two separate books: the 1964 Four Square paperback with the same title as the US,

which collected four of the original nine stories, and The Night of the Puudly from the same publisher the same year,

which collects the remaining five. Geeks like me live for this kind of stuff.)

- Worlds Without End—Belmont L92-584, 1964 (pb, collects three novelettes.

First hardcover was the UK Herbert Jenkins edition of 1965)

- Best Science Fiction Stories of Clifford D. Simak—UK, Faber and Faber, 1967 (hc); Doubleday, 1971 (hc);

Paperback Library 1972 (pb, collects seven stories.)

- So Bright the Vision—Ace Double H-95, 1968 (pb, collects four stories.

Bound with Jeff Sutton's The Man Who Saw Tomorrow)

- The Best of Clifford D. Simak—UK, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1975 (hc); Sphere, 1975

(pb, collects ten stories and a bibliography, with author's introduction.)

- Skirmish: The Great Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak—Berkley/Putnam, 1977 (hc);

Berkley, 1978 (pb, collects ten stories and author's introduction)

- Des Souris et des Robots—French, J. C. Lattes, 1981 (collects nine stories. Title translates as Of Mice and Robots.)

- La Croisade de L'Idiot—French, Denoel, 1983 (collects seven stories; can be considered as an abridgement of

The World of Clifford Simak. Tile translates as Idiot's Crusade.)

- The Marathon Photograph and Other Stories—Severn House, 1986 (hc);

Methuen, 1987 (pb, UK, paperback as The Marathon Photograph only; contains four stories and compiler's introduction)

- Brother And Other Stories—Severn House, 1987 (hc);

Methuen, 1988 (pb, UK, collects four stories and compiler's introduction)

- Off-Planet—Methuen, 1988 (hc); Mandarin, 1989 (pb, UK, collects seven stories and compiler's introduction)

- The Autumn Land and Other Stories—Mandarin, 1990 (pb, UK, collects six stories and compiler's introduction)

- Immigrant and Other Stories—Mandarin, 1991 (pb, UK, collects seven stories and compiler's introduction)

- The Creator and Other Stories—Severn House, 1993 (hc) (UK, collects nine stories and compiler's introduction)

- Over the River and Through the Woods: The Best Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak—Tachyon Publications,

1996 (hc, collects eight stories and introduction by Poul Anderson)

- The Civilisation Game and Other Stories—Severn House, 1997 (hc, UK, collects seven stories and compiler's introduction)

- Eternity Lost: The Collected Stories of Clifford D. Simak Volume 1—Darkside Press, 2005 (hc, dated internally as

2004; collects twelve stories and introduction by John Pelan)

- Physician to the Universe: The Collected Stories of Clifford D. Simak Volume 2—Darkside Press, 2006 (hc, collects

twelve stories and introduction by Barry Malzberg)

- Impossible Things—Wildside, 2010 (pb, collects four stories)

- Hellhounds of the Cosmos—Wildside, 2011 (pb, collects four stories)

In addition to the two listings just above, there have been multiple

publications of those few Simak stories which have fallen into the

public domain, too numerous to mention here. Regardless of the quality

of the various bindings and cover designs, the material remains well

above average and the reader should not reject those publications out of

hand. After all, one eats the sandwich, not the wrapper.

Non-Fiction Books

- The Solar System: Our New Front Yard—St. Martin's Press, 1962

- Trilobite, Dinosaur, and Man: The Earth's Story—St. Martin's Press, 1966

- Wonder and Glory: The Story of the Universe—St. Martin's Press, 1969

- Prehistoric Man: The Story of Man's Rise to Civilization—St. Martin's Press, 1971

Fiction and Non-Fiction Anthologies

- From Atoms to Infinity: Readings in Modern Science—Harper & Row, 1965

- The March of Science—Harper & Row, 1971

- Nebula Award Stories #6—Doubleday, 1971

Other Awards

- Minnesota Academy of Science Award for distinguished service to science 1967

- First Fandom Hall of Fame award 1973

- Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award 1976

- Bram Stoker Lifetime Achievement award 1988

Not a word of that reads as though it was written by an old-fashioned,

mid-western newspaperman, but it was. It may not be poetry, exactly, but as

prose it's effective as hell. It's to-the-point without being terse; it paints a

clear, if other-worldly picture; and it sets up the concept of the novel with a

minimum of what my old junior high English teacher used to call "Who shot

John."

Not a word of that reads as though it was written by an old-fashioned,

mid-western newspaperman, but it was. It may not be poetry, exactly, but as

prose it's effective as hell. It's to-the-point without being terse; it paints a

clear, if other-worldly picture; and it sets up the concept of the novel with a

minimum of what my old junior high English teacher used to call "Who shot

John." Of

such elements are the stories which comprise the City

sequence made. There's more than that, of course; for all the simplicity of the

prose, Simak's stories aren't at all simple.

Of

such elements are the stories which comprise the City

sequence made. There's more than that, of course; for all the simplicity of the

prose, Simak's stories aren't at all simple.

"The

Creator" was a what-the-hell story, an item that Simak almost certainly intended

as a "so long and thank you very little" gesture. The pulps hadn't been terribly

good to him, let's face it, and by and large they weren't whatcha call yer great

literature. A good deal of what was published by the editors was, frankly,

filler. There might be a couple or three good yarns in any given issue, but a

lot of the rest was cranked out by pro hacks in an afternoon, more or less.

Editors had to fill pages to keep both their readers and their advertisers

happy, and many of them (at the time, anyway) were convinced that their readers

wouldn't know schlock from Shinola if it leapt up and gnawed them on the

fundament.

"The

Creator" was a what-the-hell story, an item that Simak almost certainly intended

as a "so long and thank you very little" gesture. The pulps hadn't been terribly

good to him, let's face it, and by and large they weren't whatcha call yer great

literature. A good deal of what was published by the editors was, frankly,

filler. There might be a couple or three good yarns in any given issue, but a

lot of the rest was cranked out by pro hacks in an afternoon, more or less.

Editors had to fill pages to keep both their readers and their advertisers

happy, and many of them (at the time, anyway) were convinced that their readers

wouldn't know schlock from Shinola if it leapt up and gnawed them on the

fundament.

Think about that for a minute. The Horror Writers of America (HWA), who give

out the Stokers, define the Lifetime award as "Presented periodically to an

individual whose work has substantially influenced the horror genre." Note the

other two recipients that year, Leiber and Long, both fine writers of fantasy,

both dark and not. Simak, though?

Think about that for a minute. The Horror Writers of America (HWA), who give

out the Stokers, define the Lifetime award as "Presented periodically to an

individual whose work has substantially influenced the horror genre." Note the

other two recipients that year, Leiber and Long, both fine writers of fantasy,

both dark and not. Simak, though? He doesn't, though. Instead, he asks the entity if there's anything he can

do to make its passing easier, and as it becomes more talkative, tells it "You

should conserve your strength." There's no badgering, no harrying of the dying

energy-being, not even anger until, with its last "breath," it becomes

recalcitrant and refuses to tell him anything. Instead, he sits with it as any

human might sit with a dying stranger; so that even the most inhuman, unlikeable

life form, one with no emotional connection with (and nothing but a mild

contempt for) Humanity would not have to die alone and ignored.

He doesn't, though. Instead, he asks the entity if there's anything he can

do to make its passing easier, and as it becomes more talkative, tells it "You

should conserve your strength." There's no badgering, no harrying of the dying

energy-being, not even anger until, with its last "breath," it becomes

recalcitrant and refuses to tell him anything. Instead, he sits with it as any

human might sit with a dying stranger; so that even the most inhuman, unlikeable

life form, one with no emotional connection with (and nothing but a mild

contempt for) Humanity would not have to die alone and ignored. Enoch Wallace didn't die in the War Between the States. Instead, he was

chosen by aliens to tend the Terran depot of an intergalactic transport system,

which has remained hidden from prying Terran eyes until now, when the Gummint

notices that he's still, y'know, alive, which makes them curious. This is made

worse when the body of an alien is disinterred by a Gummint man. There were

already plenty of questions being asked—you can't be 100+ years old and not

attract some attention—and things get a little uncomfortable.

Enoch Wallace didn't die in the War Between the States. Instead, he was

chosen by aliens to tend the Terran depot of an intergalactic transport system,

which has remained hidden from prying Terran eyes until now, when the Gummint

notices that he's still, y'know, alive, which makes them curious. This is made

worse when the body of an alien is disinterred by a Gummint man. There were

already plenty of questions being asked—you can't be 100+ years old and not

attract some attention—and things get a little uncomfortable.