A Logic Named Clement (or Open the Pod Bay Doors, Hal)

His work has from the first been characterized by the complexity and compelling interest of the scientific (or at any rate scientifically literate) ideas which dominate each story. —John Clute, writing in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (St. Martin's 1993)

That's Hal Clement, all right. Even when I was a kid, we knew when we picked up a new Clement story or book that we were going to be challenged—those of us who weren't already science geeks, anyway.

Not that he was utterly abstruse, mind you. You had to know your stuff, or at least have access to a science teacher who didn't mind answering questions about "sci fi," but there was plenty of story in there to be had, even if the ideas were most important.

Of course, this endeared him to John

Campbell and the readers of Astounding/Analog (where most of his

stories appeared) for years, but he never had trouble finding an

audience wherever he went.

Of course, this endeared him to John

Campbell and the readers of Astounding/Analog (where most of his

stories appeared) for years, but he never had trouble finding an

audience wherever he went.

Several years ago, I was asked by a friend to speak to a group of middle-school faans who had decided to form a science fiction club at their school. I found them curious, enthusiastic, and eager to have anything new to read after finishing the most recent Harry Potter book. I read my own stories to them (set in their home town, which is the reason I was approached in the first place), answered their questions, and at the end, presented them with two grocery bags filled with old classic sf paperbacks: old Groff Conklin anthologies I had duplicates of, Asimov, Bradbury and Laumer collections, a few volumes of the Del Rey Best of . . . series, and whatever else I had around the house I thought they'd like (and wouldn't get them in trouble with their folks).

I still hear from some of them once in a while, and by far the author many of them are most grateful for having been introduced to is Hal Clement. Which is as it should have been; these were good, smart and clever kids, ready to delve into the ideas and concepts that Clement, a teacher himself, was keen to impart. It was a match made, well, if not in heaven then certainly above the plane of the ecliptic.

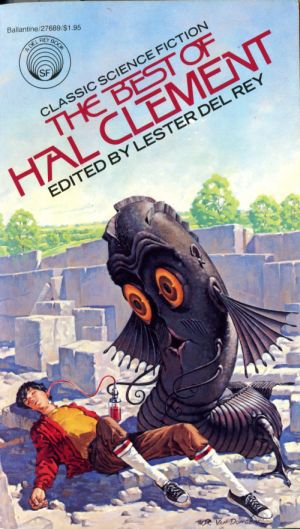

"Look," he explained it all to me once. "A writer is a man who makes his living writing. I make my living teaching. So I'm not a writer." —Lester del Rey, quoting the author in his introduction to The Best of Hal Clement (del Rey 1979)

That's a characteristically low-key self-appraisal, of course, and one could debate it all day, but why argue with the man? He knew his priorities, and his students and scouts came before publishers and editors with their eye-shades and cheap cigars. This is not to say that he didn't have a handle on how good he really was as a writer, however, as editor and publisher (sans shades and cigars) Warren Lapine recalls:

The most interesting thing I ever heard him say about his own writing was (and I'm paraphrasing here) that he (Harry) had an ego every bit as big as Isaac's (Asimov) and that he (Harry) was as good a writer as Isaac, but that Isaac had a much better press agent.

Harry Clement Stubbs was born in Somervile, Massachusetts on May 30, 1922. He

got his B. S. in Astronomy from Harvard(!) when he was 21(!!), and four years

later got his Masters in Education from Boston U. He also did grad work in

chemistry.

During WWII, he co-piloted B-24s for the Army Air Force, flying 33 combat missions in the ETO with the 8th. In the early 1950s he was recalled as a tech instructor at the special weapons school at Sandia. He taught science[i] at the Milton Academy in Cambridge, Mass. until his retirement, and if that wasn't enough, he was an avid scoutmaster the whole time.

In his spare time, he was the epitome of the hard-science sf writer, the one that all sf fans pointed to when asked who paid the most stringent attention to the laws of physics when writing about aliens, humans and other planets. In his spare time, I repeat. He did it better than anybody else at the time (and for a long time after), he was a telling and righteous influence on Sheffield, Asaro, Benford, and all the other hard-science writers who came after him, and he did all that when he wasn't teaching kids astronomy or chemistry or how to tie knots.

Do this for me. Look all the way down at the bottom of this article at the bibliography. Go ahead, I'll wait here and finish my root beer.

Did you notice something? I sure as hell did: as influential as Hal Clement was, as important as he was as a yarn-spinner, as much as his name was bandied about for, oh, five decades or so as one of the giants, he built it all on the basis of a little over fifty stories and about a dozen books. In his spare time. Doesn't that just suck?

No, it doesn't. It is, in fact, remarkable as hell. He was a remarkable individual, was Harry Clement Stubbs, and his work bears that out. He didn't cheat, he didn't fudge the numbers, and he didn't keep his eyes closed when he speculated. That wasn't what Clement was about, not at all. He was about making the story fit the science, not the other way around. Science was a suit he put on, it's what he was, and if the story had to work around the physics, it didn't work at all. Oh, he got it wrong once in a rare while, but when he did, you can bet that every pro in a labcoat had it wrong at the time, too. Nonetheless, science was never the trimmings in a Clement story, it was the whole turkey.

He sold his first story to—as should surprise none of you reading this—John Campbell's Astounding. "Proof" appeared in the June, 1942 issue, and if it didn't quite raise a fuss, it was the camel's nose, and Astounding was the tent. How could Campbell have possibly resisted a story featuring aliens who lived inside a star:

They had evolved far down near the solar core, where pressures and temperatures were such that matter existed in the "collapsed" state characteristic of the entire mass of white dwarf stars. . . . The race had evolved to the point where no material appendages were needed. Projected beams and fields of force were their limbs, powered by the annihilation of some of their own neutron substance.

O,

my little droogies, your faithful narrator would love to have been a fly on the

wall of the Street and Smith offices that afternoon. Of his fifty-plus stories, no

fewer than twenty appeared in Astounding/Analog, with his last story gracing

the pages of the January 2000 issue. That's a span of 58 years, a record few can

even come close to.

O,

my little droogies, your faithful narrator would love to have been a fly on the

wall of the Street and Smith offices that afternoon. Of his fifty-plus stories, no

fewer than twenty appeared in Astounding/Analog, with his last story gracing

the pages of the January 2000 issue. That's a span of 58 years, a record few can

even come close to.

Hal Clement's second story, "Impediment," was a carefully thought out account of the landing of a space ship near the Arctic Circle and its discovery by one man. . . . The story was interesting on an intellectual level, as are all Clement's later works, but cold emotionally. —Alva Rogers, in A Requiem for Astounding (Advent 1964)

Therein lies the focus of much of the criticism of Clement's writing, from the beginning right up until the end. Clement had the reputation for being the Mr. Spock of (real) science fiction, eschewing sentiment and emotions and stressing ideas over character. Well, yeah, but science is all about ideas, is it not? It's when you bring people into the mix that science gets all screwed up and messy and before you know it there are giant flying robots knocking off banks and cackling madmen in lab coats firing funny-colored rays at World Capitols and making Superman choose between London and Lois Lane. Right?

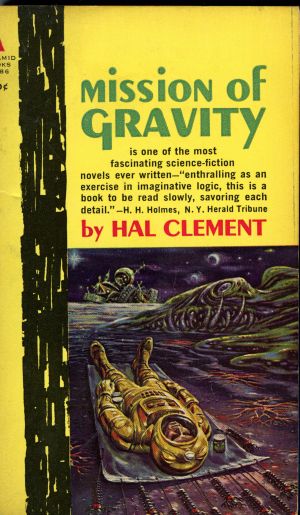

Okay, I'm exaggerating for effect. Clement's characters are perfectly acceptable as characters; just don't expect them to cry or rave or even laugh more than is necessary to get the point across. In his world, characters exist to serve the idea, not the other way around. Damon Knight noted this in his examination of Clement's best (and best-known) story, Mission of Gravity:

[Clement's] failings are a certain emotional blandness—no Clement character ever gets excited—and a low romantic quotient: where [Raymond] Gallun's monsters are alien and humanly sympathetic at the same time . . . Clement's often fail to convince simply because they're too human: more so, in fact, than some of the human characters.

Nevertheless, Knight doesn't stint his praise for the book, calling it ". . . the most back-breaking job of research ever undertaken to buttress a science fiction story. Moreover," he continues, "the result is worth the trouble." And boy-howdy, is it ever. This is the one book that is invariably mentioned whenever fans get together with other fans and talk about hard sf. When articles on the topic are written, or panels/workshops on hard science fiction are conducted by faans and pros alike, Mission of Gravity is the one title that is either praised or castigated as the ultimate case in point.

Allow me to elaborate on that Rogers quote above, if you will. As I write

this, Mary (my harshest critic and Boon Companion, Feeder of Cats and Painter on

Fabrics) has read over the first draft of this little piece and has admonished

me for my apparent dispassion towards my Subject. As is usually the case, she is

correct, but don't tell her I said that or I'll never hear the end of it,

okay?

But she's right, I'm not terribly passionate about Clement's work, for all that I've read it over and over throughout the years and eagerly grabbed stories and books I didn't already have for my personal library. There's a reason for this.

Let me be absolutely clear about it: Hal Clement is not a writer who engages the emotions. To the contrary, Clement's work appeals almost entirely to the intellect. Is this a bad thing? I think not, for many good reasons, but here's the best—Wonder is as much an object of the mind as it is the heart, perhaps more so. I'm not talking about the wonder of a rainbow here, but the Wonder of what makes that rainbow appear where before there was none.

There are plenty of very fine writers who address the emotions, in one way or another or to one degree or another. Harlan Ellison, Zenna Henderson, Edgar Pangborn, and Barry Malzberg are only a bare few whose works tweak, tap or tear at the heart. They excel at it, and their work is effective and affecting.

Hal Clement didn't play that. His interest was not in pulling strings or pushing buttons (well, not emotional ones anyway) but in taking hold of the mind and shaking it until that mind is a quivering lump of Wow! To that end, he created worlds and people—human and otherwise—who exemplify the very best of science fiction, accent on the first word. This is not an easy thing to do.

I'm no scientist, I can tell you that: when I write a story that includes a specific bit of physics or chemistry or astronomy, I get out my phone list or e-mail address book and start asking those who know better than I. I am in awe of those who don't need to do that, and trust me, Harry Clement Stubbs was awesome. He had his speculative ducks in a row before he ever put paper in his typewriter, and it really does show.

Mesklin, the planet on which Mission of Gravity takes place, is the original Discworld.[ii] During its formation, it spun so fast that the sphere flattened, and as a result, gravity is just all outta whack; a gentle three times Earth normal at the equator, but a he-man challenging 700g at the poles. Talk about needing orthotics.

Clement figured out all the accessories for a planet like this, from weather patterns to how life would have evolved (intelligent centipedes), and I can tell you for certain that he enjoyed every single minute of it. Believe me, there are those of us for whom research is an evening's entertainment, whether its figuring out the biota of an alien planet or studying up on those who do.

It is a wonderful book, and by that I mean one filled with wonder, not just a terrific read. A landmark in the field, its impact on those who read it and loved it stretches far beyond the bookstore or library shelves and further on into aerospace technology and even NASA. In a way, it really does represent science fiction just the way the Know-Nothings think it does when they point at it. They're right, of course, but for all the wrong reasons.

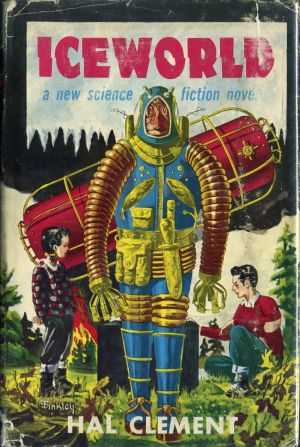

Mission

wasn't his first book, though. Before that came Needle and Iceworld. The former came about as a result of

a statement John Campbell made to Clement in hopes that the author would do just

what he did: write a story to prove him wrong.

Mission

wasn't his first book, though. Before that came Needle and Iceworld. The former came about as a result of

a statement John Campbell made to Clement in hopes that the author would do just

what he did: write a story to prove him wrong.

Campbell, let's face it, had all kinds of ideas for his own stories, and until he took over the reins of Astounding back in 1937 he did pretty well with them. Being an editor, unfortunately, means that your own career as a writer has to suffer to one degree or another, and Campbell's screeched almost to a halt; he published little fiction after taking over the Astounding post, and that in other magazines.

But there were all these ideas he had, see, and if he couldn't write 'em he sure as hell didn't see why somebody else couldn't. So, he would frequently toss an outrageous question or comment to one of "his" writers, and they quickly learned that he loved to be proven wrong, especially in his own magazine[iii].

Ergo, Needle. In a letter to the author dated April 12, 1953[iv], Campbell said, "Once upon a time I told you 'Science Fiction detective stories don't work—you can't write a good one.' So you proved that I was wrong in that, and wrote Needle."

High praise, nicht wahr? Of course, even higher praise followed in the form of checks from every editor he submitted to (in his spare time), so that even if he still listed "educator" on his QV, his hobby was plenty lucrative.

As an educator, kids were important to Clement. It shows in his writing: the protagonist of his first novel, Needle, is a teen-aged boy working with an alien symbiote detective to track down another symbiote, wherever on Earth it is, hence, a needle in an Earthstack; Close to Critical offers an Earthican robot on a heavy-gravity planet called Tenebra raising native children Earthishly, and his rescue of human children who have crashed there. Don't think that these are kids' stories, although kids can certainly enjoy them. Like another educator/writer, Zenna Henderson, Clement was writing about children, not down to them. They were important in his life, ergo they were present in his fiction.

A significant percentage of his short fiction has been anthologized and/or collected over the years, seven stories alone between 1951 and '54. One of these, "Critical Factor," was commissioned by Frederik Pohl for his Star Science Fiction original anthologies and appeared in the second volume of that inestimable series in 1953. This was not the last time Clement would contribute an original story to an anthology, either. Twenty-three years later he would give Judy-Lynn del Rey "Stuck With It" for the second volume of her inestimable series, Stellar.

Both stories bear the clear and unmistakable imprint of our beloved science teacher, for all that they don't bear resemblances to each other elsewise. Each has a primary concept used as a pivotal element around which Clement weaves his story, and both show the author's keen talent at presenting, and then (cleverly) solving, a problem based on that concept.

Sounds cold and rigid, don't it? Well, it isn't. Clement might have

been all about the science, but he was also all about the story. Anybody

can take an idea and hang words on it with a beginning, middle and end[v] and call it a "story," but it takes a real

storyteller to do it right.

Clement worked well with others on a social level, but only collaborated once in his career. In 1956, the magazine Satellite appeared with the promise of ". . . a complete science fiction novel in every issue," much as Startling had done a decade and change before. Sam Merwin, Jr., edited the first two (digest) issues, then left. Before he did, however, he added some 10k words to a story Clement wrote entirely from an alien viewpoint by inserting alternating chapters from a human perspective. It was published in the February, 1957 issue as "Planet for Plunder." As sf historian and critic Mike Ashley writes in his utterly necessary Transformations: Vol. 2, History of the Science Fiction Magazine, 1950–70 (Liverpool University Press 2005):

Clement was asked if he could pad the story out to novel length. Clement had neither the time nor the desire to do so but, with his agreement, the story was revised. . . . It was never published in book form in this version, but the original novella, "Planetfall," was eventually printed in Robert Hoskins' anthology Strange Tomorrows in 1972.

Ashley doesn't hesitate to cast a critical eye over the unfortunate result of this "collaboration," either, saying it ". . . added nothing new to the story and virtually killed it for the way Clement had planned and plotted it. In fact it's an object lesson in how to ruin a good story."

In the last years of his life, Clement suffered from diabetes. I recall a panel at a local convention[vi] in 2002 at which he sat to be interviewed by another writer/historian, Paul Dellinger, and myself. At one point, as the afternoon went on, Clement began repeating himself, slurring his words and misunderstanding questions. He caught our expressions, reached into his pocket and unfolded a bag of plain M&Ms. Carefully counting out a precise number of the little candies, he popped them into his mouth and chewed. Within moments, he was sharp again, energetic and right on top of us.

It was a typically Clementian thing to do, of course. He could never stand being fuzzy or confused, either in his writing or his daily life, and his interface with the world had to be just so. That he was "medicating" himself with candy-coated chocolate that melts in your mouth (not in your hand) instead of prescription drugs was just another clue to his meticulous approach to everything, fiction included. Why spend money on pills you can barely pronounce when you can get the same effect from shopping at any 7-11 candy aisle?

"Meticulous," he says. . . . Paul and I asked him a number of process-oriented questions that afternoon, and he remembers a comment Clement made which clearly exemplifies his habitual pains-taking, one I had since forgotten:

He did stories by writing scenes on index cards, and only when he had sufficient numbers of those would he begin actually writing the story.

Between 1994 and 1999, he wrote six stories for the DNA magazine Harsh Mistress (later Absolute Magnitude). HM/AM was, for the duration of its publication, a periodical that bubbled just under the level of its principal competitors, each issue threatening to burst through the floor and out-sell the older and more established markets. So, how did it rate an almost regular appearance by one of the Major League Hall of Famers? Editor and publisher Warren Lapine met Clement at Not Just Another Con in 1993, found him to be (as usual) very approachable, and, er, approached him:

At that point our first issue wasn't even out, but I asked him if we could get a story from him. He gave a noncommittal answer and I figured that was that. A few months later I was at another convention. . . . I was literally telling a new would-be writer that he could not just hand me a manuscript at a con and expect me to consider it when Harry walked up to me and said, "Here's the story you asked for," and handed it to me on a five-inch floppy. I, of course, said "Thank you!" and then amended what I had been saying to the new writer to, "You can't hand me a manuscript at a con and expect me to consider it unless you're Hal Clement. . . ."

That story was "Sortie," and it appeared sixteen years after his previous one. Why so long? Well, first of all, it wasn't as if Clement didn't have other things to do; recall, if you will, that his career as an author was pursued in his spare time. Lapine asked him why he'd stopped, and ". . . he told me it was because people had stopped asking him for stories." Unwilling to let that one go, and because "Sortie" was deliberately unresolved, Lapine urged him to write a sequel to tie up loose ends. Clement replied that he could do that, but that it might take three or four stories. "I was okay with that," Lapine says, "I told him 'Of course' and he wrote three more stories that ended up as the novel Half Life."

Harry Clement Stubbs left us on October 29th, 2003, at the age of eighty-three. He went quietly in his sleep, and perhaps he's somewhere still dreaming, file cards in hand and papers to be corrected stacked neatly by his elbow. The body of work he left behind isn't as extensive as many, but it's as rich and intricate as any. He left a large footprint on the Terra, and unlike all too many of his colleagues, his stories read as well now as they ever did. Warren Lapine praises him highly, saying "Harry was the nicest and easiest person I've ever worked with. I can't remember a single tense moment with him . . . I don't think he ever said an unkind word about anyone."

He was a fascinating man to talk to, filled with stories and facts, and above all, Ideas. His absence leaves a void that can never be filled by another.

Bibliography of Hal Clement

(As usual, this bibliography is as complete as I can make it given my resources, and is limited to first publications except where the same story was published under two or more titles. Also as usual, I welcome all corrections and additions; c'mon, folks, keep me honest.)

Short Stories

"Proof"—June 1942 Astounding"Impediment"—August 1942 Astounding

"Probability Zero: Avenue of Escape"—November 1942 Astounding

"Attitude"—September 1943 Astounding

"Technical Error"—January 1944 Astounding

"Trojan Fall"—June 1944 Astounding

"Uncommon Sense"—September 1945 Astounding [Laird Cunningham]

"Cold Front"—July 1946 Astounding

"Assumption Unjustified"—October 1946 Astounding

"Answer"—April 1947 Astounding

"Fireproof"—March 1949 Astounding

"Needle"—serial, May, June 1949 Astounding [Robert Kinnaird]

"Iceworld"—October-December 1951 Astounding

"Halo"—October 1952 Galaxy

"Critical Factor"—in Star Science Fiction Stories No. 2, ed. Frederik Pohl, Ballantine 55, 1953

"Mission of Gravity"—serial, April-July 1953 Astounding [Mesklin]

"Ground"—December 1953 Science Fiction Adventures

"Dust Rag"—September 1956 Astounding

"Planet for Plunder"—February 1957 Satellite (with Sam Merwin, Jr.)

"Close to Critical"—serial, May-July 1958 Astounding [Easy Rich]

"The Lunar Lichen"—February 1960 Future

"Sunspot"—November 1960 Analog

"The Green World"—May 1963 If

"Hot Planet"—August 1963 Galaxy

"Raindrop"—May 1965 If

"The Foundling Stars"—August 1966 If

"The Mechanic"—September 1966 Analog

"Ocean on Top"—serial, October-December 1967 If

"Bulge"—September 1968 If

"Star Light"—serial, June-September 1970 Analog [Mesklin; Easy Rich]

"Lecture Demonstration"—in Astounding: John W. Campbell Memorial Anthology, ed. Harry Harrison, Random House 1973

"The Logical Life"—in Stellar 1, ed. Judy-Lynn del Rey, Ballantine

"Mistaken for Granted"—January/February 1974 Worlds of If

"Longline"—in Faster Than Light, ed. George Zebrowski and Jack Dann, Harper & Row 1976

"A Question of Guilt"—in The Year's Best Horror Stories IV, ed. Gerald W. Page, DAW 1976

"Stuck With It"—in Stellar 2, ed. Judy-Lynn del Rey, Ballantine 1976

"Seasoning"—September/October 1978 Asimov's [Medea]

"Sortie"—Spring/Summer 1994 Harsh Mistress

"Settlement"—Fall/Winter 1994 Absolute Magnitude

"Seismic Sidetrack"—Spring 1995 Absolute Magnitude

"Simile"—Summer 1995 Absolute Magnitude

"Oh, Natural"—Spring 1998 Absolute Magnitude

"Exchange Rate"—Winter 1999 Absolute Magnitude

"Under"—January 2000 Analog [Mesklin]