In a Klass By Himself (or, Tops On a Scale of One to Tenn)

I never met Phil Klass face-to-face, which (it goes without saying) means I

never met his alter ego, William Tenn. Unless you define "meet" as "encounter,"

in which case I met him during the Golden Age of SF: i.e., when I was about ten

years old.

I don't recall which specific Tenn story was my first, but it may very well have been either his very first story, "Alexander the Bait" (which I would have read in Groff Conklin's Omnibus of Science Fiction, Crown 1952) or "Child's Play," his second story, reprinted by Conklin in A Treasury of Science Fiction, published by Crown four years earlier.

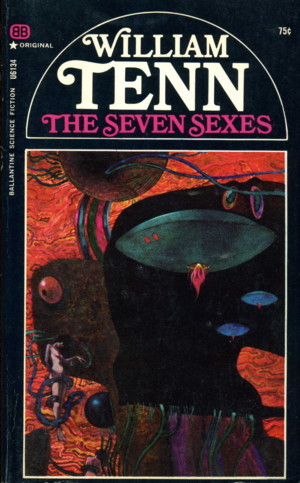

Not that it matters, really, since I was an ardent fan of William Tenn from whenever I first ran across him. I recall clearly the plans I had for my weekly pay when I was sixteen and delivering papers in the hills around Roanoke. I had a long list of albums (Mothers of Invention, Electric Prunes, Yardbirds and other soft-rock hits) and books I wanted to buy, and among them was the lovely little matched six-volume set of William Tenn stories that Ballantine brought out in 1968. I had to get them one at a time, as they came out, but I was proud of that little row of books and I showed them off to my other sf-reading friends.

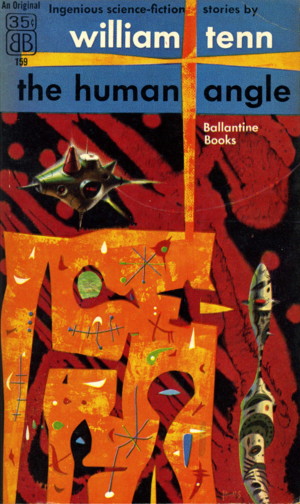

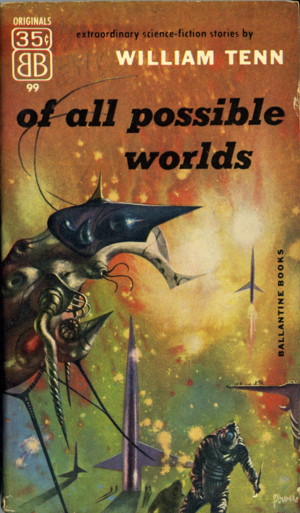

Those original copies were lost in one move or another, but I've subsequently acquired another set, all in fine condition, and I still show them off to people, given the slightest encouragement. It doesn't bother me in the least that two of them—Of All Possible Worlds and The Human Angle—weren't first editions in that set, since I've also managed to track down perfectly nice copies of those originals as well; that the other four are, in fact, original publications is just icing on an already tasty cake.

Phil Klass (not to be mistaken, of course, for the UFO-debunker of the same name) didn't leave an extensive oeuvre, but what's there is, in the words of Spencer Tracy, "cherce." He wasn't a particularly poetic writer, although he came close from time to time, nor did he show the elegance of prose that Cordwainer Smith or Alfred Bester so often gave their readers.

What he had, and had by the bagful, was humanity. Oh, don't get me wrong, there's plenty of the Marx Brothers in his stuff, but just as often there's more than a hint of Charlie Chaplin. Klass could make you laugh out loud, but there was always an undercurrent of compassion in his writing that made you engage with his characters all that much more.

This is more important than you might think, and far more difficult than

almost anyone understands. Humor depends on a number of things in able to work.

In order for it to work, and to work well, they all have to be kept in the air at once.

Timing, delivery, concept, build-up, gag: when one of these falls flat, they all

fall flat, and nobody but another humorist can say that the others might still

have come off. Nothing is less funny

than something which is supposed to be hilarious—and isn't.

This is more important than you might think, and far more difficult than

almost anyone understands. Humor depends on a number of things in able to work.

In order for it to work, and to work well, they all have to be kept in the air at once.

Timing, delivery, concept, build-up, gag: when one of these falls flat, they all

fall flat, and nobody but another humorist can say that the others might still

have come off. Nothing is less funny

than something which is supposed to be hilarious—and isn't.

Phil Klass understood this at his core, and although his stories might not be Shecky Hackett/stand-up comic funny, they're still funny as hell. Stories, I should point out, aren't the correct vehicle for stand-up humor—the few times it's been tried by various writers, it's fallen even flatter than a CD-ROM in a punch-press—but they're a perfect vehicle for a funny situation, and here is where Klass shone.

In one of his first "2,000 Year-Old Man" routines with Carl Reiner, Mel Brooks defined humor thusly: "Tragedy is when I have a hangnail, comedy is when you step into an open manhole and die." This is a little black-and-white, but it's accurate enough as a general rule of thumb for us to work with. Let's face it—"America's Funniest Home Videos" wouldn't have stayed on the air for twenty years had it not been for this particular rule, nor would the Three Stooges still set newer and newer generations of kids howling in front of their after-school TVs.[i]

(Well, okay, we could debate that for a long time without actually coming to anything resembling a consensus about anything except that Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner are as funny as two adult human males can get.)

But comedy isn't the same thing as humor. Comedy is of-the-moment, here and now, and fast as a fat guy in a top hat and tails slipping on the ice. Humor (especially satire, Klass's forté) is extended, lingering, sustained; humor is the funny story, comedy is the punchline.

Phil Klass was all about the sustained humor of satire. Never satisfied with

mere punchlines, he took us through the whole process of funny, spinning out his

yarns bit by bit, injecting cross-cultural humor as required by his stories'

concepts. Klass was Jewish, so naturally the humor in his work is predominately

so. However, it isn't exclusively Jewish—Klass is just as adept at finding

universal ways to make us laugh as he is at the ethnic stuff. But his cultural

roots (as well as influences as widely diverse as Bernard Malamud and Sholem

Asch) are evident even in those stories which occur far enough into the future

that (let's face it) there would be very few people speaking in traditional

Yiddish cadences.

Phil Klass was all about the sustained humor of satire. Never satisfied with

mere punchlines, he took us through the whole process of funny, spinning out his

yarns bit by bit, injecting cross-cultural humor as required by his stories'

concepts. Klass was Jewish, so naturally the humor in his work is predominately

so. However, it isn't exclusively Jewish—Klass is just as adept at finding

universal ways to make us laugh as he is at the ethnic stuff. But his cultural

roots (as well as influences as widely diverse as Bernard Malamud and Sholem

Asch) are evident even in those stories which occur far enough into the future

that (let's face it) there would be very few people speaking in traditional

Yiddish cadences.

Doesn't matter. Science Fiction isn't ever about the future, even when it's set there; it's about the Now, and part of the effectiveness of his humor was the juxtaposition of, say, the archetypal equivalent of a Brooklyn candy store owner in, say, a colony on Venus. Other writers tried to use this trope and failed at it. Klass could make it work because that's the way it worked for him. He knew funny, and was one of the lucky handful of writers who could actually get it right on paper.

Klass was no mere Borscht Belt tummeler, though, nor was he a one-trick pony, however good that trick might be. Satire is easy to find in sf, especially in the first decade or so of both Galaxy and F&SF: Kornbluth, Kuttner, Goulart, Brown, and Sheckley were only a few of the authors whose wry takes on subjects like television, psychiatry and advertising kept H. L. Gold and Boucher & McComas supplied throughout the 1950s and '60s.

But Phil Klass offered more than just lampoons of popular cultural icons, he gave the reader a sense of humanity, without which satire is mostly just, well, punchlines. He honestly liked people, and even though he was more than conscious of their foibles and frailties, he firmly believed in their kindnesses and empathy.

In one of my personal favorites, "On Venus, Have We Got a Rabbi" (written for Wandering Stars, ed. Jack Dann, Harper 1974), Klass (as Tenn, of course—when I speak of one, I also mean the other) tells of a problem of Talmudic proportions: aliens want to become Jews.

So what? you might ask. Well, leaving aside the fact that Jews don't

proselytize, there are traditional aspects of Judaism—mostly what makes a Jew a

Jew and what doesn't—that have been part of history since the very first

yarmulke appeared on the very first kopf. How can an alien, a Bulba at that, be a

Jew?

So what? you might ask. Well, leaving aside the fact that Jews don't

proselytize, there are traditional aspects of Judaism—mostly what makes a Jew a

Jew and what doesn't—that have been part of history since the very first

yarmulke appeared on the very first kopf. How can an alien, a Bulba at that, be a

Jew?

Why not? you might again ask. There's a reason, hence the conflict that must be resolved here: Bulbas are not just aliens—the blue people from Aldeberan are aliens, and they're Jews—they're inhuman aliens. They're described in the story as ". . . brown pillows, all wrinkled and twisted, with some big gray spots on this side and on that side, and out of each gray spot is growing a short gray tentacle."

The problem here isn't that they're different, it's that they're too different. "A Jew can be blue," the protagonist tells his son, ". . . and a Jew can be tall or short. He can even be deaf from birth like those Jews from Canopus, Sirius, wherever they come from. But a Jew has to have arms and legs. He has to have a face with eyes, a nose, a mouth. It seems to me that's not too much to ask."

Milchik, the narrator, is not the only one who is opposed to the Bulbas calling themselves Jews, this is a controversy that threatens the whole colony's well-being.

The solution is both properly Talmudic and properly science-fictional, and in resolving the conflict Klass shows us that even brown, cockroachy pillows can be endowed with a Human-ness that transcends their non-humanity. It's a warm, funny, compassionate story that leaves the reader with a feeling of deep satisfaction. That it was written a good seven years after his last published story is testament to Klass's aptitude, and a refutation of the old saw that those who can't, teach.

Didn't I mention that before? Phil Klass had a day job, from 1966 on,

teaching writing and matters stfnal at Penn State. I can only imagine what it

must have been like to sit in his classroom; his likable personality and

communication skills must surely have enabled him to reach and influence his

students over the years.

Didn't I mention that before? Phil Klass had a day job, from 1966 on,

teaching writing and matters stfnal at Penn State. I can only imagine what it

must have been like to sit in his classroom; his likable personality and

communication skills must surely have enabled him to reach and influence his

students over the years.

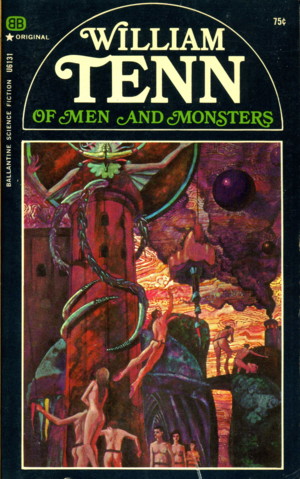

A day job was necessary, since Klass's period of greatest output was during a time when many sf/fantasy magazines were disappearing, some almost overnight. He didn't write the long form, at least not much. His only two books-published-as-novels were A Lamp for Medusa (originally "Medusa Was a Lady!") and Of Men and Monsters (originally "The Men in the Walls"), and both stories were actually novellas, not full-length novels.

In James Gunn's The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (Viking 1988), Brian Stableford wrote this about Klass:

Tenn's strength as a writer lies in the sensitivity that allowed him to identify and dramatize the pathetic as well as the comic aspects of his ironic situations, giving stories such as "Down Among the Dead Men" (1954) and "Time Waits for Winthrop" (1957) an unusually poignant dimension.

I can't argue with that. "Poignant" is quite a well-chosen word here, in

fact, especially in regard to the first story Stableford mentions, an

atypically nasty little tale about a prolonged war and the technology

that enables those fighting it to constantly repair and restore

wounded—dead!—soldiers and return them to the fight. No

candy-store ethnic humor here, no gags, no laughs; there's satire

a-plenty, but it's dark, grim, bitter. It's a quietly brilliant story,

told with subtlety and elegance. I wish Klass had written more like it,

if only to silence those who would dismiss him as just another

gagster.[ii] Damon Knight had some

uncharacteristically nice things to say about an earlier story in his

review of Robert Heinlein's[iii] one-off anthology,

Tomorrow, the Stars in his collection of criticism, In Search

of Wonder (Advent: Publishers 1957), a story which doesn't even

appear in the book he's reviewing:

. . . "Liberation of Earth" (Future, May 1953)—the funniest story [Tenn's] ever written, and about as equivocal as a punch in the solar plexus . . . If I'm right, it merely proves what needs no proof, that Tenn is another artist who won't stop till he's had the last word.

This truly funny story wasn't reprinted until 1968, when it was included in the Ballantine collection Of All Possible Worlds, but has been reprinted several times since. I urge you to seek it out.

"Down Among the Dead Men" and "Time Waits for Winthrop" came from H. L. Gold's Galaxy, the magazine where Klass found his greatest editorial welcome and most appreciative readership. From his first sale to Gold in 1951 until his last (to Frederik Pohl) in 1963, fully half of his output appeared in what was at the time the most important challenger to Campbell's Astounding.

Klass and Galaxy were matched perfectly. Satire was the magazine's strong suit, as I've said, and Klass's skill at sending up almost anything without betraying even a hint of contempt made him a favorite. Galaxy also gave him a platform for his more serious work, without which he might have never been able to stretch his wings as he did with ". . . Dead Men".

In all, Phil Klass published sixty-three stories from his first in 1946 to his last in 1993, a double handful of articles, and edited two anthologies, one of them in collaboration with Donald E. Westlake. I wrote an article about his sf anthology[iv], and when it appeared, he actually called to thank me. He was so certain that he'd been completely forgotten—when Mary answered the phone, he introduced himself somewhat forlornly and was both surprised and moved when she immediately responded that she knew his work and had read his stories.[v]

We talked for more than an hour, about the book and his own stories, his career, other writers[vi] and just Stuff. I found him to be bright, personable, funny as hell, and grateful that I'd thought his book was worth writing about. It led to other conversations, phone and e-mail, and a promise that he would approach the editor of the SFWA Bulletin about the possibility of writing a series of articles about his career.

Alas, his health intervened, and it never came to pass. However, his work speaks loudly and clearly on its own, appealing to any reader who is searching for wit and wisdom, for both pathos and joy, for meaning. I heartily recommend the three volumes of his fiction and non-fiction published by NESFA and listed at the end of the bibliography below. There are damned few authors whose (nearly) complete works can be had in three hefty volumes, and even fewer whose (nearly) complete works contain almost no filler. I can think of little else more worth your time and money.

A Bibliography of William Tenn

(As usual, this biblio represents initial appearances only, and is almost certainly incomplete. By all means, if you have additions or corrections, feel free to let me know. Seriously. I want this to be as accurate as possible.)Short Stories

"Sonnet"—? 1935 Cargoes (poem)

"Anecdote"—? 1939 Apprentice (vignette)

"The Apotheosis of John Chillicothe"—? 1939 Apprentice

"Eleven P.M."—? 1939 Apprentice (vignette)

"Incident Gourmandien"—? 1939 Apprentice (vignette)

"Alexander the Bait"—May 1946 Astounding

"Child's Play"—March 1947 Astounding

"Mistress Sary"—May 1947 Weird Tales

"Errand Boy"—June 1947 Astounding

"Me, Myself, and I"—Winter 1947 Planet Stories (as by Kenneth Putnam)

"The House Dutiful"—April 1948 Astounding

"Dud"—April 1948 Thrilling Wonder Stories (as by Kenneth Putnam)

"Confusion Cargo"—Spring 1948 Planet Stories (as by Kenneth Putnam)

"Consulate"—June 1948 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Ionian Cycle"—August 1948 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Brooklyn Project"—Fall 1948 Planet Stories

"The Human Angle"—October 1948 Famous Fantastic Mysteries

"The Remarkable Flirgleflip"—May 1950 Fantastic Adventures

"The Puzzle of Priipiirii"—July 1950 Out of This World Adventures

"The Last Bounce"—September 1950 Fantastic Adventures

"Null-P"—January 1951 Worlds Beyond

"The Quick and the Bomb"—Spring 1951 Suspense Magazine

"Betelgeuse Bridge"—April 1951 Galaxy

"Hallock's Madness"—May 1951 Marvel Science Stories

"A Matter of Frequency"—May 1951 Science Fiction Quarterly

"Venus Is a Man's World"—July 1951 Galaxy

"Everybody Loves Irving Bommer"—August 1951 Fantastic Adventures

"The Jester"—August 1951 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Medusa Was a Lady!"—October 1951 Fantastic Adventures

"'Will You Walk a Little Faster'"—November 1951 Marvel Science Fiction

"Firewater"—February 1952 Astounding

"Ricardo's Virus"—March 1953 Planet Stories

"Liberation of Earth"—May 1953 Future

"The Custodian"—November 1953 If

"Project Hush"—February 1954 Galaxy

"The Tenants"—April 1954 F&SF

"Down Among the Dead Men"—June 1954 Galaxy

"Party of the Two Parts"—August 1954 Galaxy

"The Servant Problem"—April 1955 Galaxy

"The Flat-Eyed Monster"—August 1955 Galaxy

"The Discovery of Morniel Mathaway"—October 1955 Galaxy

"The Sickness"—November 1955 Infinity Science Fiction

"Murdering Myra"—November 1955 Suspect Detective Stories

"Wednesday's Child"—January 1956 Fantastic Universe

"Time in Advance"—August 1956 Galaxy

"She Only Goes Out at Night"—October 1956 Fantastic Universe

"Of All Possible Worlds"—December 1956 Galaxy

"Time Waits for Winthrop"—August 1957 Galaxy

"The Dark Star"—September 1957 Galaxy

"Sanctuary"—December 1957 Galaxy

"Eastward Ho!"—October 1958 F&SF

"Lisbon Cubed"—October 1958 Galaxy

"The Malted Milk Monster"—August 1959 Galaxy

"The Men in the Walls"—October 1963 Galaxy

"Bernie the Faust"—November 1963 Playboy

"The Masculinist Revolt"—August 1965 F&SF

"My Mother was a Witch"—August 1966 P.S.

"The Lemon-Green Spaghetti-Loud Dynamite-Dribble Day"—January 1967 Cavalier

"The Last Bounce"—April 1967 Amazing

"The Remarkable Firgleflip"—July 1967 Fantastic

"On Venus, Have We Got a Rabbi"—in Wandering Stars, ed. Jack Dann, 1974

"There Were People on Bikini There Were People on Attu"—The Best of Omni Science Fiction #5, 1983

"The Girl with Some Kind of Past. And George."—October 1993 Asimov's

Articles

"7 Out of 10 Astrogators Choose Venus!—Marvel Science Fiction August 1951

"The Fiction in Science Fiction—Science Fiction Adventures March 1954

"The Frank Merriwell Compulsion or Winning the Championship the Hard Way"—April 1963 Rogue

"The Student Rebel: Then and Now"—June 1966 P.S.

"The Bugmaster"—? 1968 True (also as "Mr. Eavesdropper")

"Jazz Then, Musicology Now—F&SF May 1972

"An Innocent in Time: Mark Twain in King Arthur's Court"—December 1974 Extrapolation

"From a Cave Deep in Stuyvesant Town—A Memoir of Galaxy's Most Creative Years"— in Galaxy: Thirty Years of Innovative Science Fiction, ed. Frederik Pohl, Joseph D. Olander & Martin H.

Greenberg, Playboy Press 1980

"'The Lady Automaton' by E. E. Kellett: A Pygmalion Source?"—in Shaw: The Annual of Bernard Shaw Studies 1982, Pennsylvania State University Press 1982

"It Didn't Come from Outer Space"—in The Digital Deli, ed. Steve Ditlea, Workman 1984

"The Enormous Toothache"—? 1985 Stories

"What's Wrong with My Daughter?"—? 1992 The Reader's Digest (as by Philip Klass)

"Constantinople"—U.S. Catholic, 1994

"Curiosities: Dr. Arnoldi, by Tiffany Thayer, 1934"—F&SF August 1998

"Author Emeritus Speech: Given Here Without the Gestures, Intonations and Pauses Which Made It Moderately Funny in the First Place"—The Bulletin of the Science Fiction and Fantasy

Writers of America #143, 1999

"Welles or Wells: The First Invasion from Mars"—Synergy SF: New Science Fiction, ed. George

Zebrowski, Gale Group/Five Star 2004; revised from an earlier version in The New York Review of Books 1988 as by Philip

Klass

Novels/Collections

Of All Possible Worlds—Ballantine 99, 1955 (collects 7 stories)

The Human Angle—Ballantine 159, 1956 (collects 8 stories)

Time in Advance—Bantam A1786, 1958 (collects 4 stories)

A Lamp For Medusa—Belmont B60-077, 1968 (a Belmont Double, bound with Dave van Arnam's The Players of Hell)

Of Men and Monsters—Ballantine U6131, 1968

The Seven Sexes—Ballantine U6134, 1968 (collects 8 stories)

The Square Root of Man—Ballantine U6132, 1968 (collects 9 stories)

The Wooden Stars—Ballantine U6133, 1968 (collects 11 stories)

Immodest Proposals: The Complete SF of William Tenn, Vol. 1—NESFA Press, 2001 (collects 33 stories)

Here Comes Civilization: The Complete SF of William Tenn, Vol. 2—NESFA Press, 2001 (collects 27 stories and 1 article)

Dancing Naked: The Unexpurgated William Tenn—NESFA Press, 2004 (collects 36 non-fiction essays and articles)

Anthologies

Children of Wonder—Simon & Schuster 1953 (collects 19 stories and 1 poem)

Once Against the Law—with Donald E. Westlake, MacMillan 1968 (collects 22 mystery stories)

[i] Frankly, all that's different now from when I was a kid is that my great-nephews are watching Larry, Moe and Curly on DVD instead of Channel 13. They still run around the house afterwards yelling "WUBWUBWUBWUB!" and calling each other "knuckleheads" while their mothers despair and their sisters think they're idiots. So did mine, so did mine, and so it goes.

[ii] Well, okay. If he had written more "serious" stories, I'd also have had a lot more really good reading, but that would be pampering myself.

[iii] Actually, Frederik Pohl and Judith Merril did most of the work; Heinlein wrote the intro and approved their choices.

[iv]Children of Wonder, in case you're unaware (it appeared in paperback as Outsiders: Children of Wonder).

[v] "Of course I know who you are!" she said when he introduced himself, and she later told me that he almost cried.

[vi] He mentioned that he used to sell copies of the anthology to a bookshop in the Village, and one day as he was going in, a young Bob Dylan was coming out of the folk club upstairs. They spoke for a while, and Klass's recollection was of an intense but friendly young man who expressed an interest in his work as a writer.