She

did a hell of a job, and within three years had assembled and delivered her very

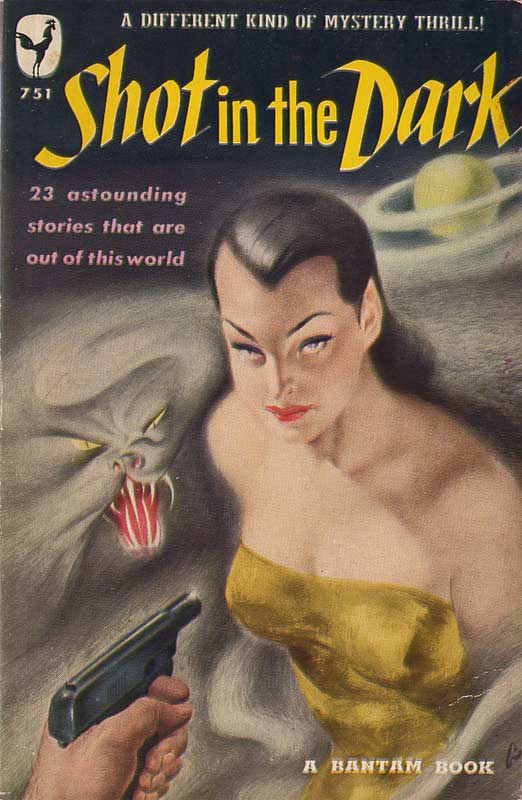

first sf anthology: Shot in the Dark, Bantam 751. Her lengthy dedication

is dated September, 1949; the book itself is copyright 1950.

She

did a hell of a job, and within three years had assembled and delivered her very

first sf anthology: Shot in the Dark, Bantam 751. Her lengthy dedication

is dated September, 1949; the book itself is copyright 1950. By Bud Webster

Merrily We Roll Along or, That's Funny, You Don't Look Judith

Wonder—informed, thoughtful, purposeful wonder—is loose on the Earth again. And this is what "SF" means, what "science fiction" is: not gimmicks and gadgets, monsters and supermen, but trained wonderment—educated and disciplined imagination—a marvelous mirror for Modern Man and the world he is only beginning to make.—from the editor's introduction, Fifth Annual of The Year's Best SF, 1960.

Judith Merril was mid-way through her productive career at the time she wrote those words. I suspect that she came to her understanding of what sf was (to her, at least) early on, and I very much doubt she changed her mind about it as she grew older. It's as workable a definition as I've ever seen, especially in a concise fifty words, and she was as qualified to hold an opinion on the subject as anyone else on the sf scene.

I had cause to write about Our Current Subject a few years ago in another place. I was examining two of her early anthologies, ones that had shown her determination to look beyond the limits of genre publication for material, a trait that she would exhibit throughout her career. Here's what I said:

. . . [S]ome of the best anthologists were also some of the best writers. One only need mention Damon Knight, Robert Silverberg, Fred Pohl and August Derleth to make that particular case.Or you could just say "Judith Merril" and be done with it.

That is as true now as it was when I originally wrote it. What is also true is the fact—unfortunate, perhaps—that Merril is better remembered now as an anthologist than as a writer. This is unfair, however accurate it may be, because much of Merril's writing sits squarely in the top percentile of the field, and almost all of it is elegant and expressive. I'm not alone in this assessment; writing in James Gunn's The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (Viking 1988), Stephen Goldman wrote, "The sum of Merril's impact on science fiction is far greater than her output in the field." She produced memorable and important work in the genre both as a writer and as an anthologist, and in this issue's installment of Past Masters, we'll be examining both these aspects of her career.[i]

Born January 21, 1923 as Josephine Juliet Grossman—some sources cite her middle name as Judith, which she clearly preferred—Merril was a zealous Zionist at the advanced age of . . . ten. That's right, ten. When you were ten, did you even know who the Speaker of the House was? I sure as hell didn't. I barely knew that the veep was Lyndon Johnson, and might not have known that if it hadn't been for Earl Doud's First Family comedy albums.

She became disillusioned with it after the USSR signed a treaty with Hitler in '39, but not until after spending most of the preceding decade at Zionist summer camps(!) and reading the Communist Manifesto. She met her first husband, Dan Zissman, at—I hope you're sitting down for this one, cowboy—a Trotskyite Fourth of July picnic in Central Park. Gotta love New York. They married in 1940, when she was but 17.

Yup, even for science fiction, Judith Grossman was a weird kid. Of course, our Shared World is rife with weird kids, but she didn't just push the envelope, she shoved it off the cliff.

Zissman was a science fiction fan, and he introduced his new wife to it; she took to her new interest with the same passion with which she once denounced running-dog capitalists. He was drafted in 1942, the same year their daughter, Merril, was born.

Zissman's problem was that couldn't stop being a radical (at least in relation to the officers above him), and that and his record of having attempted to unionize a defense plant got him transferred from a cushy gig at the San Francisco radar school to Pearl Harbor.

Mother and daughter went back to New York and fell in with a bunch of political no-goodniks: the Futurian Society of New York. Yeah, those guys again. That connection, as was the case with any number of other pioneers in the field, changed everything.

Judith Zissman began hanging out with these unsavory characters, most of them radicals like herself ("radical" by WWII standards, that is, what with several of them also being members of the Communist Youth League), folk like Isaac Asimov, Fred Pohl, Damon Knight, James Blish, Donald Wollheim, Cyril Kornbluth, Robert "Doc" Lowndes, Hannes Bok, and Larry Shaw. Pretty serious list of names there, as you may have noticed.

(Face it, the Futurians were just about the most important and influential fan groups in the world, let alone NYC. They would write, edit, illustrate and/or publish an enormous amount of the sf written from the late 1930s until the end of the war. In fact, in one way or another, they would tend to dominate the field well into the 1960s-70s. Anyone who considers him/herself to be conversant with the history of sf in America and who underestimates the significance of this little group of faans to the development of modern speculative fiction is on dangerous conceptual ground. Who's your stfnal daddy? The Futurians, hoss, and make no mistake about it.[ii])

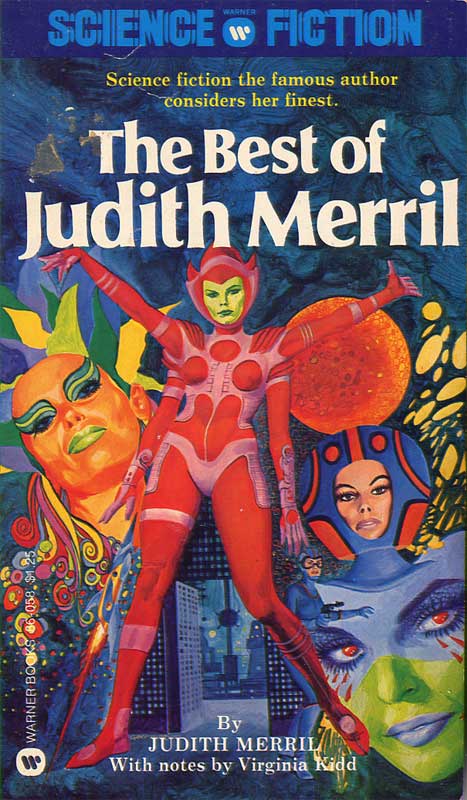

Merril wasn't intimidated in the slightest by the seething political morass she found herself in, though. Remember that remarkable ten year-old? A dozen years sure as hell hadn't dimmed her lights. Future agent extraordinaire Virginia Kidd recalled those days in her introduction to The Best of Judith Merril (Warner 86058, 1976):

Judith Merril was a revelation to me. I had never before known a politically conscious female. . . . I had never known a woman who could outthink me as often as she could outtalk me—not always, but often enough so that I could as easily have disliked her as admired her. . . . This is the best of Judith Merril for me: she knew a lot of the answers before most people realized that there might be, ought to be, questions.

All that added up to this: in 1945, Judith Grossman Zissman moved in with Kidd, adopted her daughter's given name as her professional surname, and Judith Merril sprang full-blown from her own brow. Of such uncanny chains of events are our beloved legends often born, n'cest pas?

All this hanging out with sf writers/editors/illustrators/faans had its inevitable effect, and Merril plunged over the edge of the precipice and began working as a researcher and ghostwriter for the Scott Meredith Agency and also writing on her own. Not sf, or fantasy, mind you, but a genre which was at the time one of the most popular and to which almost every one of our Old Favorites contributed at one time or another: the Sports pulps. Under pseudonyms like "Eric Thorstein" and "Ernest Hamilton," she sold a number of yarns to magazines like Sports Leader, Sports Short Stories, and Sports Fiction. Using the same pen-names she also wrote filler material for some of the Western pulps.

Her first sale wasn't science fiction, fantasy, or even football, however, but a mystery, "No Heart for Murder," to Futurian "Doc" Lowndes (she'd workshopped the story through the group) for the July 1945 issue of Crack Detective Magazine. A few months later, "The 'Crank' Case" appeared in the same magazine. Both were published under her married name, Judy Zissman. However, although they were her first actual sales, neither was her first publication. In 1939, a story titled "The Golden Fleece" appeared in something called The Tower as by Judith Grossman; I have no direct evidence of this, but given her age at the time—sixteen—I suspect it was a high school literary magazine.

None of this really mattered except that it was the beginning of an important career. She didn't stomp on the stfnal Terra until the June 1948 issue of Astounding hit the stands and the sf-reading world was confronted by one of the most moving and chilling stories Campbell would ever publish: "That Only a Mother."

On the assumption that a good percentage of you reading this haven't yet had the, er, pleasure, I won't spoil this disturbing little story for you. I will go so far as to mention that it involves radiation and motherhood. For me, it's more than enough proof that Campbell was a far more able and discerning editor that he's frequently given credit for these days; there's precious little of the problem/solution, smart Terran/dumb alien story he's often blamed for in this one.

The story behind the story is an interesting one, if you're anything like the process-tweak that I am. She ran the story through the Meredith Agency first—in those days, agents were happy to get ten percent of two cents a word—and it was read by Arnold Hano, who was chief reader at the time. He said:

Scott had received her story, "[That] Only a Mother", and he tossed it to me to see if it was marketable. I read it and went crazy over it. He sent it out to Collier's . . . and it bounced back with a weird comment that the editor never wanted to see another story by this writer. . . ."

As I said in that other, earlier article, Hano's recollection isn't dead-on. In Better to Have Loved: The Life of Judith Merril (Between the Lines 2002, completed from Merril's notes by her grand-daughter, Emily Pohl-Weary), the Collier's rejection is reproduced. The text is clear; the editor who bounced the story was, to say the least, appalled by the subject matter, but concludes by saying that she would "like very much to see more of this author's work."

Whatever his recollections might be, Hano championed the story. When Collier's bounced it, he sent it back to Scott Meredith with a note that said (in part), "If you don't get $1,000 for this you ought to quit."

After the war, Arnold Hano went on to become managing editor at Bantam Books (under Ian Ballantine), still fairly new after a 1945 start-up. Bantam wanted to create a mystery line, and Hano immediately suggested Merril. Not content with making her wear the snap-brim Fedora, they asked her to wear their space helmet too, and put her in charge of their sf line.

She

did a hell of a job, and within three years had assembled and delivered her very

first sf anthology: Shot in the Dark, Bantam 751. Her lengthy dedication

is dated September, 1949; the book itself is copyright 1950.

She

did a hell of a job, and within three years had assembled and delivered her very

first sf anthology: Shot in the Dark, Bantam 751. Her lengthy dedication

is dated September, 1949; the book itself is copyright 1950.

Looking at the cover, you'd never know it was science-fiction or fantasy. An exotic woman stares intently at the reader, décolletage visible but discreet, her raven hair combed straight back over her head in a vicious widow's peak. From the lower left, we see a man's hand pointing an automatic pistol directly at her, light glinting off the muzzle. Pretty damned hard-boiled, I'd say, barring the lack of a trench-coat. The only things that give it away are fairly subtle (for 1940s pulp fiction covers, anyhow): a misty, ringed planet behind her in the upper right, a spectral cat floating at her right shoulder, and her decidedly pointed ears.

The text at the top promises "A different kind of mystery thrill!", which must have amused many of the authors within—Heinlein, Sturgeon, Leinster, Asimov, and Tenn among others. Why the odd presentation? Well, as much as Bantam trusted Merril to do a good job, they just weren't sure about this science-fiction thing, so they packaged the book as a mystery, as much as was possible. I have to admit that it's a lovely little thing, colors far more muted than you'd expect from pulp fiction, and the contents are just terrific. I won't list them here (much as I'd like to), but you can check it out at William Contento's Index to Science Fiction Anthologies and Collections, Combined Edition, located at http://www.philsp.com/homeville/ISFAC/0start.htm, along with any other anthology or collection you want to dig into.

This first book was well-received (no matter the mixed message the art and blurbs gave the reader), selling out quickly and eventually going through several printings. It would lead directly to invitations to do other, more extensive anthologies.

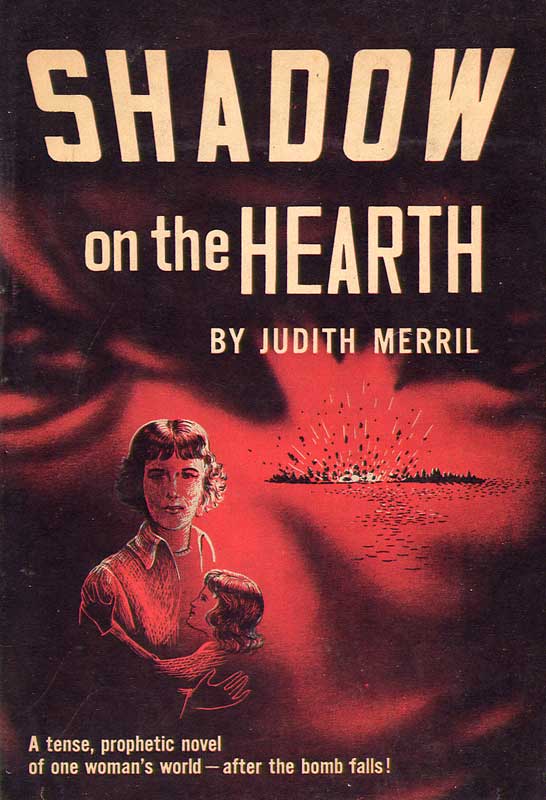

However, before it did, Doubleday published her first novel, A Shadow on the

Hearth, also in 1950. One of the first novels to deal with the aftermath of

atomic war, it's still one of the best. As with "Only a Mother," it deals with

a woman coping with the horrors and dangers of life after a nuclear war, although

the wife and mother in the novel is far more adaptive and capable than the mother

in the earlier story. She is caught where no post-WWII housewife would have wanted

to be—alone with her daughters while her husband desperately tries to get

back home from the city.

However, before it did, Doubleday published her first novel, A Shadow on the

Hearth, also in 1950. One of the first novels to deal with the aftermath of

atomic war, it's still one of the best. As with "Only a Mother," it deals with

a woman coping with the horrors and dangers of life after a nuclear war, although

the wife and mother in the novel is far more adaptive and capable than the mother

in the earlier story. She is caught where no post-WWII housewife would have wanted

to be—alone with her daughters while her husband desperately tries to get

back home from the city.

In the hands of a lesser writer (dare I say a male one?), Shadow could have been merely a blatant exercise in ham-handed satire: June Cleaver, in pearls and apron, meets the Fallout Monster and gives it what-for; or, worse, merely a disaster novel concerned only with blasted landscapes and ludicrous stereotypes. Instead, we're given a strong, resolute woman who belies categorization as a weak, indulged suburban hausfrau, tackling not only the perils of radiation and life without amenities, but the horny and determined guy next door. As a story of atomic awareness, it is perhaps dated; as a character study of strength found through adversity, it's still a solid and rewarding read. Thus began the literary career of one of the most important writers, anthologists and critics in the field. Her footprint may not have been huge, but she cast a long and lingering shadow. As Spencer Tracy said of Katherine Hepburn in "Babe," "There ain't much meat on her, but what's there is cherce."

As good as her first novel is, though, her next solo long-form effort was, well, let's just say problematic. The Tomorrow People was published in 1960 by Pyramid Books as a paperback original. The story, taken by itself, is fine: Johnny Wendt is disheartened by his experiences on Mars, experiences he can't even talk about, but which involve a fellow spaceman's disappearance on the Red Planet. His girlfriend, Lisa, wants to help him, but is unable to penetrate the psychological wall he's built around himself. Worse, there are pages missing from the ship's log, which creates even more (and not terribly compelling) complications.

There are other characters, including the psychiatrist who's trying to "cure" Johnny while being hopelessly in love with Lisa (as is every other male in the book) and a gaggle of military and political cyphers who all have their own agendas.

For whatever reason, here Merril doesn't seem to be as involved with her characters as elsewhere. There's an overall flatness, the characters are less developed, and there's little to engage the emotions of the reader. That, perhaps, is not the worst of the book's faults, sorry to say.

Judith Merril was many things, most of them admirable and commendable, but she was no scientist. For most of her work, this isn't really a drawback. Her stories deal not so much with technology as with her characters attempts to cope with it, and by and large this was a successful tack for her.

In The Tomorrow People, though, she somehow managed to have a helicopter work on the moon. Our moon, the one with no discernable atmosphere. She'd have done as well to write in a glider, frankly, and for many (myself included, which says as much about me as it does the book), this failure to stick to fact makes it difficult to enjoy the story. I mean, you'd expect this sort of thing from, say, Pel Torro, but not the author of "Dead Center." It's much like the Hollywood convention of having a private eye empty a .45 automatic pistol at a criminal only to have the gun click several times as it goes dry; that ain't the way the technology works, and those who are aware of it trip over the silliness and lose interest.

Damon Knight, that most erudite of stfnal critics (as well as fellow Futurian/Hydra), set aside his very real affection for the author and in his collection of reviews and essays, In Search of Wonder, published by Advent in 1956 wrote:

What is objectionable in the book is its lack of any internal discipline, either in the writing or the thinking. Under the crisp surface it is soft and saccharine: wherever you bite it, custard dribbles out.Is this the "woman's viewpoint"? I don't believe it; I think it is the woman's-magazine viewpoint, from which God preserve us.

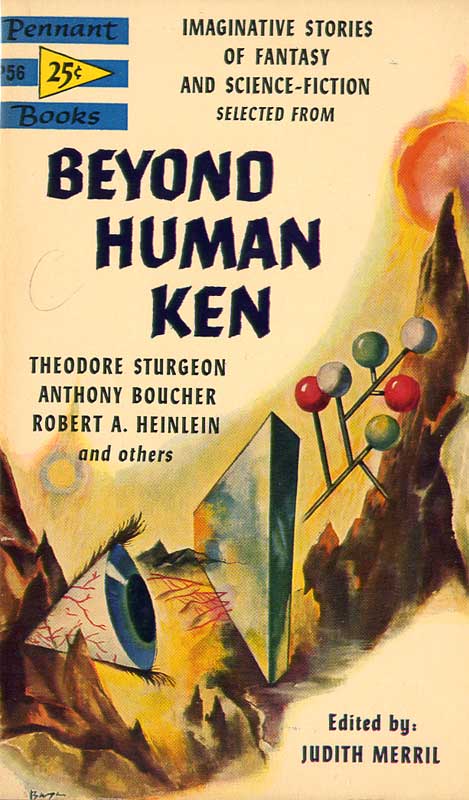

After

Shadow was published, she assembled and produced two hardcover anthologies:

Beyond Human Ken and Beyond the Barriers of Space and Time for Random

House in 1952 and '54 respectively. Now, the first of these two powerhouse books

was pretty well centered on the genre magazines of the time; only one of the stories,

Stephen Vincent Benet's "The Angel Was a Yankee," came from an outsider periodical,

namely the October 1940 McCalls, of all places. The others were gleaned

from the Usual Suspects, except for a single original from Laurence Manning, "Good-Bye,

Ilha!".

After

Shadow was published, she assembled and produced two hardcover anthologies:

Beyond Human Ken and Beyond the Barriers of Space and Time for Random

House in 1952 and '54 respectively. Now, the first of these two powerhouse books

was pretty well centered on the genre magazines of the time; only one of the stories,

Stephen Vincent Benet's "The Angel Was a Yankee," came from an outsider periodical,

namely the October 1940 McCalls, of all places. The others were gleaned

from the Usual Suspects, except for a single original from Laurence Manning, "Good-Bye,

Ilha!".

In Beyond the Barriers, however, she would further develop her penchant for looking outside the stfnal box, choosing stories from Esquire, New Yorker, Saturday Evening Post, and a vintage Agatha Christie story, "The Last Séance," from the November 1926 Ghost Stories.[iii]

As much as I love this hefty pair of hardbacks, Merril's really revolutionary works were to come not long after; before we get to those, we'll take time to consider her own distinct perspective on the rightly-beloved "year's best sf/fantasy" trope.

The first book to pass judgment on the best sf stories of the year was put together by the "team" of Everett F. Bleiler and Thaddeus E. Dikty and was published by Frederick Fell in 1949 under the title The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1949. It may seem a bit presumptuous to issue a book of the year's best in the same year it titularly covers, but "1949" refers only to the year the book came out; the stories themselves ran in '48. Bleiler and Dikty would continue their series together until 1954, and Dikty would carry it on for another two years alone.

In the meantime, Donald Wollheim would create Prize Science Fiction for McBride in 1953 as the first in a series of year's best, but a disagreement with the publisher cancelled that project at the very beginning.

Merril would do her first annual retrospective in 1957 with SF:57 The Year's Best Science Fiction for Gnome Press. Like the B&D book, it covered not the year in the title but the one previous, and unlike the other series (which stayed pretty close to home, stfnally) it presented the reader with a number of stories from non-genre publications like The London Observer, Playboy, Esquire and Harper's. Again, we see not just a willingness on the part of the editor to look in the corners, but a determination to do so and to do so well.

Merril poured herself into this endeavor with enthusiasm and skill. Her association with the Futurians (and later, the Hydras) and her marriage to Frederik Pohl (from 1949-53) would provide her not only with a broad knowledge of literature but contacts throughout the publishing world. This would make it even easier to seek out the beyond-the-pale stories and other material she would present to the readers in the dozen volumes of her year's best series, and give her the insight and courage to offer such off-the-wall choices as cartoons (by Fleischer, Walt Kelly and others), articles, and verse. No one else would have the balls to spread their nets that far until Harry Harrison and Brian Aldiss inaugurated their Best SF series in 1967.

You wouldn't

think this was so much of a much until you realize that Merril's visionary concept

of what constituted "Best" indicated a perspective of science fiction far in advance

of practically every other anthologist at the time, by a good ten years at least.

She demonstrated this perspective in other ways as well: she was instrumental

in creating the seminal Milford Conferences with fellow authors/critics Damon

Knight and James Blish in 1956, which would lead directly to the founding of the

Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America in 1965. Her image of speculative

literature as a vital and essential part of all fiction led her to create a body

of anthological work that transcends the Gernsbackian roots of the genre and anticipates

the revolution of the mid- to late sixties. Over the years the series was active,

you can see the contents moving gradually—if doggedly—away from the

merely traditional and towards the decidedly experimental. This would culminate

in two very remarkable books.

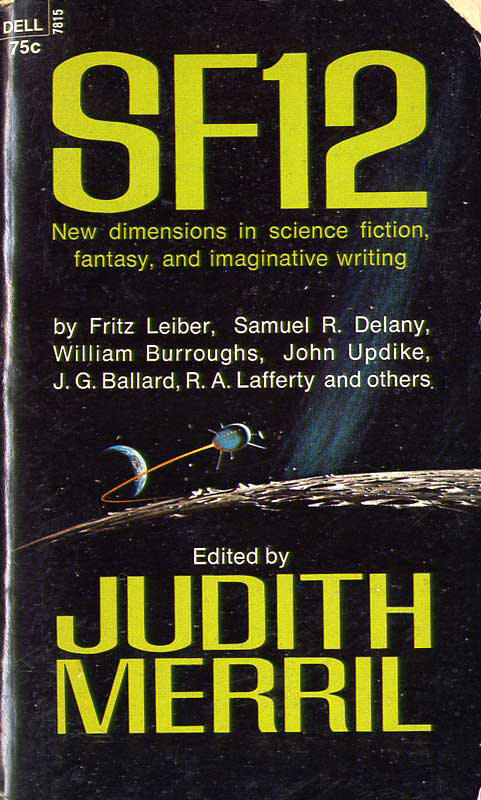

The first was the final volume of her year's best series, titled simply SF12. Thirty individual pieces (the other volumes ran from eleven to thirty-six), half of them from Outsider sources, including four poems from then-Fug Tuli Kupferberg and another verse from Tom Disch. From within the field, she chose stories by Kit Reed, Ballard, Bob Shaw, Aldiss, Lafferty, and Delany (as well as others), but the prizes here are the names that I'd wager the average sf reader knew only by reputation, if at all: Tommaso Landolfi, Donald Barthelme, John Updike, William Burroughs(!), Henri Michaux, and Gunther Grass, author of The Tin Drum. What on earth must have gone through the heads of teen-age Boomers as they read their way through this madness? I know I was seriously challenged by the contents of this hefty book at the age of sixteen, but—and here's the vital factor at work—I trusted Judith Merril to hand me readable and engaging work.

Oh, believe me, I didn't know what to make of Grass, or Barthelme, and I'd only just learned of Burroughs and hadn't yet read any, but how cool was it that she included poetry by a member of the Fugs[iv]? At the time, I was the only person I knew who'd ever even heard of the Fugs, let alone listened to any of their albums. And here was this woman, this Judith Merril, this old adult person (she was forty-five at the time. "Old.") who not only knew about them but wanted to publish poetry by one of them. Yow.

I'm not joking. This book was, as I look back on it now, a turning point for me. It prepared me for new literature the way that listening to John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen prepared me for avant-garde music. Had it not been for this book, and her next one, I would never have been able to fathom Dangerous Visions and its follow-up a few years later. I doubt that I'm alone in this regard, either, as I still sell as many copies of SF12 as I can get my hands on, mostly to people my age or a bit older, eager to relive the experience or to introduce it to their kids/grandkids.

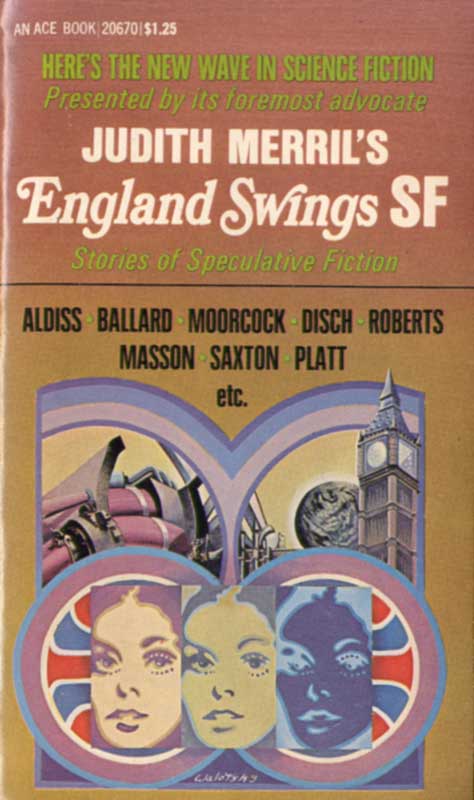

As important as SF12 was, though, it pales beside her next anthology, the hideously titled England Swings SF.[v]

In the year this anthology

was published, John Brunner won the Hugo for his mosaic novel Stand on Zanzibar;

Robert Silverberg won for his novella "Nightwings"; Harlan Ellison for the short

story "The Beast that Shouted Love at the Heart of the World"; and Poul Anderson

walked away with the rocket for his novelette "The Sharing of the Flesh."

In the year this anthology

was published, John Brunner won the Hugo for his mosaic novel Stand on Zanzibar;

Robert Silverberg won for his novella "Nightwings"; Harlan Ellison for the short

story "The Beast that Shouted Love at the Heart of the World"; and Poul Anderson

walked away with the rocket for his novelette "The Sharing of the Flesh."

Things were changing. Only a few years before, Heinlein had won for The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, with Jack Vance and Larry Niven taking the short fiction awards. Both writers and readers were becoming more erudite, eschewing "space opera" and looking for more mature and complex stories. Ellison's ground-breaking anthology, Dangerous Visions, lit the way for a revolution of sorts and the spotlight was on experimentation in both concepts and techniques. To many, it was a rude and objectionable intrusion into their comfortable world of time machines, robots and spaceships, and there was an enormous amount of ink spilled both in decrying and defending what quickly became known as the New Wave. Where did it come from, this wholesale transformation of genre from pulp to sophistication?

Good question.[vi] The Milford Conferences, organized as I said before by Knight, Blish and Merril, certainly pre-dated and foreshadowed the mid-60s madness, but in its own way the work that resulted was fairly conservative—at least in relation to what would be done a few years later in England.

The history of the UK magazine New Worlds deserves far more space than I'm able to give it here, but I'll hit a few high spots. It was begun in 1946 as the continuation of a pre-WWII fanzine edited by John Carnell, who remained at the helm until 1964 when Michael Moorcock took over. Carnell was certainly no slouch as an editor (his anthology series, New Writings in SF lasted for twenty-one volumes under his guidance and showcased many new writers), but it was Moorcock who twisted the beast's tail and let it fly.

New Worlds spearheaded what would soon become known as the New Wave[vii], and fostered the early careers of many of the "movement"'s stars: Josephine Saxton, J. G. Ballard, Thomas Disch, Keith Roberts, Charles Platt, Chris Priest and Brian Aldiss were only a few of the authors who saw key work published there. Harlan Ellison's Nebula-winning "A Boy and His Dog" saw its first publication in New Worlds.

Merril, who was living in London at the time, was very impressed by what she read there and in a few other UK magazines, and she was determined to make the best of it available to US readers. Thus was born one of the most important anthologies of the 1960s, and one which would confound, frustrate and even infuriate more traditional sf fans and pros.

England Swings SF, for all the cheesiness of the title, was a vital and necessary exploration of what science fiction could be if authors were left unfettered to write what and as they wanted. Yes, much of the experimentation was influenced by non-genre writers from much earlier in the century, but most of those writers were largely unknown at the time to all but academic readers. I'm not going to spend a lot of time defending it—Ghu knows there was a lot of very bad writing issued as "New Wave"—but as an evolutionary step in the development of science fiction as literature, it was absolutely crucial.

So, what of the book? It is, in a word, brilliant. Forget the arguments in the fanzines and prozines of the day, ignore the pronouncements the pundits issued vilifying their Opponents, and never mind the knee-jerk cries of "Blasphemy!" heard from the Old Guard. Here is the only thing that matters: story. Story, plain and simple. Or, in the case of much of the contents of this book, rich and complex.

See, it doesn't matter how many typographic tricks or oddball formats you use, if you don't have much of anything to say. If you don't engage the readers' emotions and intellect, you can use all the fonts and page designs you want and the reader won't get past page three. Catch the reader up in the web of your story, though, and they'll be willing to forgive anything unusual, especially if it enhances their experience.

Merril, writer/editor/critic that she was, knew this, and she skimmed the cream for England Swings SF. Don't underestimate this substantial little book, you're going to be challenged even today by many of the stories herein. That speaks to the value of the work, and all I can say is that you'll be rewarded for the effort.

I'm going to drop any pretense at objectivity at this point and tell you my initial reaction to one of the stories, specifically Ballard's "The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered as a Downhill Motor Race." [viii]

I hated it. I despised it, I railed against it and I hocked metaphorical lugies at it and its author. On those occasions when I spoke of the New Wave to others, this was the story I pointed to as exemplar of how wrong-headed the "movement" was.

But . . . it haunted me. It provoked me, yeah, and it pissed me off (for me, the Kennedy assassination was as sacred as the Crucifixion—and I wasn't alone), but I couldn't get it out of my head. I re-read it. Then I re-read it again. It still angered me, but I was beginning to understand that it was supposed to. This wasn't some English snob snorting derisively at my dead president, it was an intellectual examination of the events that occurred in Dallas and the people involved. The very intellectualism of it was awash in emotion, and it carried me along like a rip-tide. It is an inspired and virtuoso performance, one I still find painful to observe, for all that I now recognize that it must be read over and over to get its full impact.

Another striking story is Pamela Zoline's "The Heat Death of the Universe," about which I have written elsewhere; I can do worse, I suppose, than to quote myself:

Its format is experimental, a sort of by-the-numbers timeline of a woman going mad. Little by little, Zoline deftly shows us piece by piece how entropy is realized directly and specifically in the life of one Sarah Boyle. Although I recall a number of faans and pros alike decrying this story (and others like it) as unreadable and even as "anti-literature" (in the sense of matter/anti-matter), the proof of any pudding is how it tastes after 40 years in the fridge, and to me this one is still pretty yummy.

The constraints of a deadline prevent me from going into further detail of this fascinating book, but it is readily available online. If you're curious, drop the few bucks the Ace paperback will set you back and devote some time and thought to it.

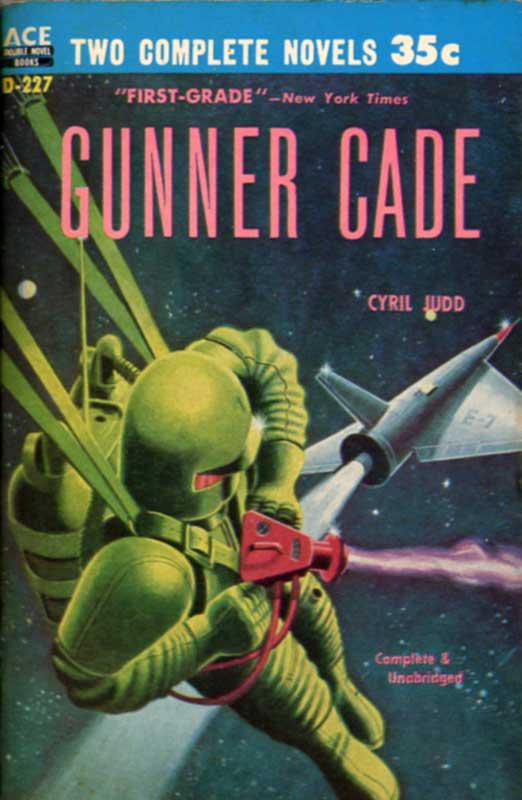

Although Merril hung with both Futurians and Hydras, and even married one or two,

she didn't choose to collaborate with any of them except Fred Pohl (one story,

"Big Man With the Girls" in the March, 1953 Future as by James McCreigh)

and Cyril Kornbluth [ix], with whom she wrote two novels,

Gunner Cade (1952) and Outpost Mars (also 1952), and the story "Sea

Change," all as by Cyril Judd.

Both novels are good but not outstanding; the reason for that may be the simple fact that Kornbluth had not yet written a novel on his own and wouldn't until he wrote Takeoff (also 1952) [x]. Merril had, but only the one. I suspect that they perhaps hadn't gotten their long-form chops yet. It could also be that Merril just plain didn't work well with others, as I'm unaware of any other confirmed collabs. I can also readily imagine potential ego-clashes between two equally talented—and self-confident—authors.

As you look over the bibliography below, don't be fooled by the low numbers. Judith Merril was no Murray Leinster as far as quantity is concerned, but she was just as skilled a story-teller and, from a purely literary standpoint, more so. I say this as a long-time Leinster fan, too. It's all about story, y'all, and if Leinster had his inventiveness, Merril was eat up with erudition. Ain't nothing but a thing.

Merril moved to Canada for political reasons in 1968, telling Robert Fulford (editor of Saturday Night, a Canadian magazine):

My feeling was that in Canada I could at least offer some usefulness or assistance to some of the guys who had come [to avoid the draft]—who didn't have the choices I had . . .

This began yet another phase of her remarkable career, one which echoed her life-long love of books and learning, and to which she devoted not only an enormous amount of time, but her personal holdings as well.

In 1970, she donated her extensive sf/fantasy collection to the Toronto Public Library to create the Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation and Fantasy, known until 1990 as the "Spaced Out Library." Why the change? I asked Collection Head Lorna Toolis:

The name was changed in 1990 to honour Judith, over her strenuous objections. The Friends [of the Merril Collection] were also acting upon advice from the Chairman of the Library Board, who gently told them that the Library Board was finding it difficult to get funding from City Council for the Spaced Out Library because the '60s were long gone, and cute wasn't traveling well.

Subsequent donations from others has built up a reference collection of more than 70,000 books (including a complete set of Arkham House) and 25,000 magazines. Altogether, there are 1700 graphic novels, 6000 non-fiction books about sf/fantasy, and 500 gaming-related material. The rest are novels and anthologies.

Sort of makes what you and I have on our shelves pretty limited, right? Never fear, though; if you find yourself in Toronto, you can make use of the Merril Collection for your masters thesis or just a few hours' reading. The books no longer circulate, but it's worth the trip just to fondle Leah Bodine Drake's A Hornbook for Witches (Arkham 1950), of which there are only a few hundred copies. I'm not sure I'd ever leave the place once I got in.

Looking back at what I've written, I realize that there's much left out. Can't help that, really, as I have neither time nor space for the book-length examination that Merril deserves. Back up there near the beginning I mentioned the autobiographical book that Emily Pohl-Weary assembled from Merril's notes, but as valuable as that volume is, there are flaws in it. Don't blame grand-daughter Pohl-Weary for that, as I suspect that the notes left behind by Merril were as casually slap-dash as those for her reviews for F&SF.

Judith Merril was named SFWA's Author Emeritus for 1997, and although I attended the Nebula Awards that year in Kansas City, Merril was unable to be there due to illness. I had been looking forward to meeting her and telling her how much I enjoyed her work, both as fictioneer and anthologist, and I regret that I was never able to do so.

She passed on September 12, 1997, leaving behind a legacy perhaps less broad than others', but as deep as anyone's.

[i] Well, I mean I will. You can look over my shoulder if you want, just don't chew so damn loud. And quit humming.

[ii] There's plenty of ink out there about this fascinating group, but in my own decidedly unhumble opinion the two best references are Frederik Pohl's The Way the Future Was (del Rey 1978) and Damon Knight's The Futurians (John Day 1977). Copies are available online for cheap enough that you can satisfy your curiosity without having to forfeit your daily latté.

[iii] I'll say little more of these two wonderful (and full-of-wonder) books, as I covered them pretty thoroughly several years ago in a column subtitled "Two Steps Beyond" published in the Fall, 2006 SFWA Bulletin. Back issues are available from the SFWA website.

[iv] Haven't you Googled 'em yet, youngster? Do so. While you're at it, check out Frank Zappa and the Holy Modal Rounders, too. Primus ain't got nothing on those guys.

[v] Not her choice, as I understand it. Put the blame on Larry Ashmeade at Doubleday, who wanted to capitalize on the popularity of the Roger Miller hit. Bleah.

[vi] As if I'd ask a dumb one.

[vii] Merril is credited with coining the term. I can't say for certain that she did, but I've found no evidence that anyone else used it prior to her in referring to the revolutionary fiction it came to describe.

[viii] I trust I'm not stealing Ballard's thunder by noting that his primary influence—aside from the assassination itself—was Alfred Jarry's "The Crucifixion Considered as an Uphill Bicycle Race". Jarry was influential in other areas as well, vis. Pere Ubu, the late '70s experimental band formed by David Thomas who took the name from Jarry's play, Ubu Roi.

[ix] See "Cyril With an M (or I'm As Kornbluth as Kansas in August)" a couple of issues ago.

[x] Clearly Kornbluth was pretty busy in 1952, wouldn't you say?

(As is always the case, the following bibliography is as complete as I can reasonably make it given time and resources. There is much missing in the Non-Fiction/Criticism section, especially that material published in Japan; that material is available elsewhere on the Web.

Shadow on the Hearth—Doubleday,

1950

The Tomorrow People—Pyramid G502, 1960

Gunner Cade—(with

C. M. Kornbluth, as by Cyril Judd, originally serialized in the March-May 1952

Astounding) Simon & Schuster, 1952; Ace Double D-227, 1958 (bound with

Crisis in 2140 by Piper and McGuire)

Outpost Mars—(with

C. M. Kornbluth, as by Cyril Judd, originally serialized as "Mars Child" in the

May-July 1951 Galaxy) Abelard, New York, 1952; Dell 760, 1953; Beacon 312,

1961 (revised, as Sin in Space)

Out

of Bounds—Pyramid G-499, 1960

Daughters of Earth—Gollancz

1968; Dell 01705, 1970

Survival Ship—Kakabeka, 1974

The

Best of Judith Merril—Warner, 1976

Daughters of Earth and Other

Stories—McClelland & Stewart, 1985

"The

Golden Fleece"—The Tower, 1939; reprinted in Bakka Magazine #6,

1977 (as by Judith Grossman)

"No Heart for Murder"—July 1945 Crack

Detective Stories (as by Judy Zissman)

"The 'Crank' Case"—January

1946 Crack Detective Stories (as by Judy Zissman)

"Horsethief Hero"—December

1947 Blue Ribbon Western (article, as by Judy Zissman)

"Five Men Don't

Make a Team"—Winter 1947 Big Book Sports (as by Ernest Hamilton)

"Pass

for Arabella"—December 1947 Double Action Western (as by Ernest Hamilton)

"Strike 'im Out"—December 1947 Western Action (as by Eric Thorstein)

"Section Gang"—January 1948 Complete Cowboy (as by Ernest Hamilton)

"That Only a Mother"—June 1948 Astounding

"Squaw Fever"—January

1948 Blue Ribbon Western (as by Eric Thorstein)

"Dry Dust"—February

1948 Double Action Western (as by Eric Thorstein)

"Goldplated Greenhorns"—February

1948 Double Action Western (as by Ernest Hamilton)

"Five Men and Fate"—March

1948 Sports Short Stories (as by Ernest Hamilton)

"Golfer's Girl"—Toronto

Star Weekly, 1949

"Death is the Penalty"—January 1949 Astounding

"Outlaw, Ride for Me!"—January 1950 Real Western Romances (as

by Eric Thorstein)

"Barrier of Dread"—July/August 1950 Future

"Survival Ship"—January 1951 Worlds Beyond

"A Woman's Work

is Never Done!"—March 1951 Future

"Mars Child"—serial,

May-July 1951 Galaxy

"Gunner Cade"—serial, March-May 1952 Astounding

(with C. M. Kornbluth, as by Cyril Judd)

"Whoever you Are"—December 1952

Startling

"Hero's Way"—November 1952 Space

"A Little

Knowledge"—February 1953 Science Fiction Quarterly

"Big Man With

The Girls"—March 1953 Future (with Frederik Pohl, as by James McCreigh)

"Sea Change"—March 1953 Dynamic Science Fiction (with C. M. Kornbluth,

as by Cyril Judd)

"So Proudly We Hail"—in Star SF Stories, ed.

Frederik Pohl, Ballantine 16, 1953

"Daughters of Earth"—in The Petrified

Planet, ed. John Ciardi, Twayne, 1953

"Stormy Weather"—Summer 1954

Startling

"Rain Check"—May 1954 Science Fiction Adventures

"Peeping Tom"—Spring 1954 Startling Stories

"Connection Completed"—November

1954 Universe

"Dead Center"—November 1954 F&SF

"Project

Nursemaid"—October 1955 F&SF

"Pioneer Stock"—January

1955 Fantastic Universe

"Exile from Space"—November 1956 Fantastic

Universe

"Homecalling"—November 1956 Science Fiction Stories

"The Lady was a Tramp"—March 1957 Venture (as by Rose Sharon)

"Woman of the World"—January 1957 Venture (as by Rose Sharon)

"Wish Upon a Star"—December 1958 F&SF

"Death Cannot Wither"—February

1959 F&SF (with Algis S. Budrys?)

"The Deep Down Dragon"—August

1961 Galaxy

"One Death to a Customer"—June 1961 Saint Mystery

Magazine

"Shrine of Temptation"—April 1962 Fantastic

"Muted

Hunger"—October 1963 Saint Mystery Magazine

"The Lonely"—October

1963 Worlds of Tomorrow

"One Does Not (Have to) Equal Empty"—January

1967 New Worlds

"In the Land of Unblind"—October 1974 F&SF

Shot in the Dark—Bantam

751, 1950.

Beyond Human Ken—Random House 1952; Bantam P56, 1954

(edited, as Selections From Beyond Human Ken)

Beyond the Barriers

of Space and Time—Random House 1954

Human?—Lion 205,

1954

Galaxy of Ghouls—Lion Library LL25, 1955; Pyramid G-397,

1959 (as Off the Beaten Orbit)

SF: The Year's Greatest Science Fiction

and Fantasy—Gnome 1956; Dell B103, 1956

SF:'57:

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy—Gnome 1957; Dell B110,

1957 (as SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy, Second Annual

Volume)

SF:'58: The Year's Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy—Gnome

1958; Dell B119, 1958 (as SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy,

Third Annual Volume)

SF:'59: The Year's Greatest Science Fiction and

Fantasy (Gnome 1959; Dell B129, 1959 (as SF: The Year's Greatest Science-Fiction

and Fantasy, Fourth Annual Volume)

Fifth Annual of the Year's Best

S-F—Simon & Schuster 1960; Dell F118, 1961 (as The Year's Best

S-F, Fifth Annual Edition)

Sixth Annual of the Year's Best S-F—Simon

& Schuster 1961; Dell 9772, 1962 (as 6th Annual Edition, The Year's Best

S-F)

Seventh Annual of the Year's Best S-F—Simon & Schuster

1962; Dell 9773, 1963 (as 7th Annual Edition, The Year's Best S-F)

Eighth

Annual of the Year's Best S-F—Simon & Schuster 1963; Dell 9774, 1964

(as 8th Annual Edition, The Year's Best S-F)

Ninth Annual of the

Year's Best S-F—Simon & Schuster 1964; Dell 9775, 1965 (as 9th

Annual Edition, The Year's Best S-F)

Tenth Annual of the Year's Best

S-F—Delacorte 1965; Dell 8611, 1966 (as 10th Annual Edition, The Year's

Best S-F)

Eleventh Annual of the Year's Best S-F—Delacorte

1966; Dell 2241, 1967(as 11th Annual Edition, The Year's Best S-F)

SF: The Best of the Best—Delacorte 1967

SF12—Delacorte,

Aug '68; Dell 7815 1969

England Swings SF—Doubleday 1968;

Ace 20670, 1968

Tesseracts—Press Porcepic 1985.

Merril supplied book reviews for The F&SF from March, 1965 until February, 1969; these were frequently turned in on whatever scraps of paper she had at hand rather than typed.

She also wrote a two-part critical piece titled "What Do You Mean, Science? Fiction?" for the journal of the Science Fiction Conference in the Modern Language Association, Extrapolation, edited by Thomas Clareson. It is still used in academic sf courses by many colleges and universities.

In addition, she wrote introductions and headnotes for her own books, as well as intros for others.

"Mars—New World Waiting"—August 1951 Marvel

Science Fiction

"The Hydra Club"—November, 1951 Marvel Science

Fiction

"Theodore Sturgeon"—September 1962 F&SF

"Japan:

Hai!"—in OSFIC #24, 1970.

"Science: Myth Tomorrow, Magic Yesterday"—February

1972 Issues & Events

"Basil Tomatoes a la Ipsy Wipsy"—in Cooking

Out Of This World, ed. Anne McCaffrey, Ballantine 1973

"The Three Futures

of Eve"—September 11, 1976 The Canadian

"Close Encounters of a

Monstrous Kind"—May 6, 1978 Weekend Magazine

"Beverly Glen Copeland"—Canadian

Women's Studies, 1978.

"Questions Unasked, Issues Unaddressed"—Perspectives

On Natural Resources—Symposium II, ed. Page, Sir Sandford Fleming College,

1979.

"The Future of Happiness"—January 1979 Chatelaine

"Jamaica:

A View from the Beach"—April 1981 Departures

"The Crazies are

Dying"—September 25, 1986 NOW

"Public Disservice"—Quill

and Quire, 1994.

"Message to Some Martians"—Visions of Mars,

CD Rom, Virtual Reality Laboratories, Inc., 1994

Better to Have Loved:

The Life of Judith Merril—comp. by Emily Pohl-Weary, Between the Lines

2002

"Auction Pit"—in Survival Ship,

Kakabeka, 1974

"In the Land of Unblind"—F&SF, 1974

"Space

is Sparse"—Daughters of Earth and Other Stories, McClelland &

Stewart, 1985

"Woomers"—Unpublished; written for a poetry reading at

Harbourfront Benefit for Pages Bookstore in 1985.