By Bud Webster

Let

Me Be Frank (or Welcome to the Allamagoosa Russell-Palooza!)

Eric Frank Russell (who heartily dislikes writing about himself) was born on January

6, 1905, at Sandhurst, Surrey, England. . . . He says he is still dizzy from fighting

his way through courses in chemistry, physics, building and steel construction,

quantity surveying, mechanical draftsmanship, metallurgy and crystallography.

. . . He has a number of ambitions: - to become a social parasite;

- to

write a story with which he is still thoroughly satisfied one year later;

- to

entertain so many readers so well that some may have a momentary regret when they

bury him;

- to type with more than two fingers.

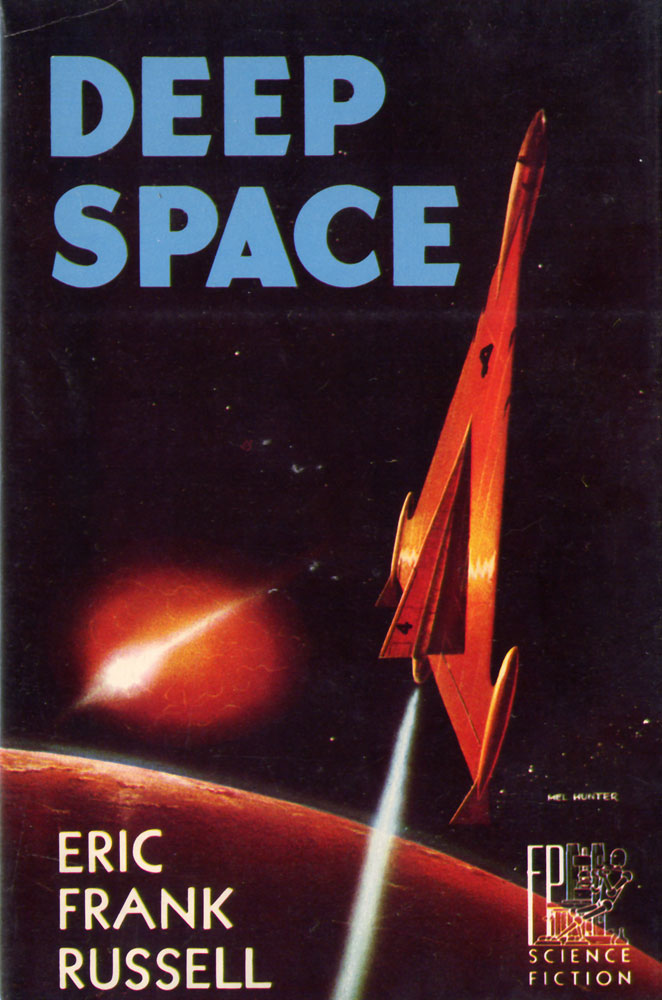

So Russell wrote of himself (like it or not) in the back cover copy of his 1954

Fantasy Press novel, Deep Space. "Age forty-seven, look like fifty-seven,

feel like thirty-seven, act like twenty-seven, think like seven," he said a year

earlier on the back of Sentinels of Space (Bouregy & Curl). "I think

that is all anyone could possibly care about. Oh, yes—I fiddle around trying

to write stories."

"Fiddle around," he says. Would that we all could "fiddle around" as well. Russell

may have been ironically self-effacing up there, but the fact is he wrote a lot

of terrific stories, including one that was so good, legend has it, that John

W. Campbell had to create a magazine to fit around it. I'll get to that a little

later, though.

"Fiddle around," he says. Would that we all could "fiddle around" as well. Russell

may have been ironically self-effacing up there, but the fact is he wrote a lot

of terrific stories, including one that was so good, legend has it, that John

W. Campbell had to create a magazine to fit around it. I'll get to that a little

later, though.

Russell has already told us where and when he was born. I'll

add that he was raised in Egypt, served honorably with the RAF in WWII, and worked

as telephone operator, quantity surveyor and "draughtsman"; certainly the UK equivalent

of cab-driving, encyclopedia salesman and fast-food manager, all typical writers'

jobs (it says here). He was a founding member of the British Interplanetary Society,

which is where he first ran into people like Arthur C. Clarke. You know, the 2001

guy.

It was there in the Society that he found science fiction, and decided

to "fiddle around" with it. In fact, his first attempt, a story titled "Eternal

Re-Diffusion," was based on an idea given to him by one of the other founders,

one Leslie J. Johnson. He sent it to what was then the pre-eminent sf magazine

in the US (and thus, the world, this being the mid-'30s and all), Astounding Stories,

as it was then known. The editor, F. Orlin Tremaine [i],

bounced it as "too difficult" for his readers. Okay, that begs the question of

what Campbell might have said, but he wasn't given a chance to decide, apparently.

The story finally saw print in 1973 in a UK chapbook, The Harbottle Fantasy

Booklet #3. Russell and Johnson did collaborate on a more successful yarn,

"Seeker of To-Morrow" for the July, 1937 Astounding.

Russell's first

sale was "The Saga of Pelican West," which appeared in the February issue of that

year. His third story, "The Prr-r-eet," included a plot element given Russell

by none other than the young (20 years old) Arthur C. Clarke. Russell shared the

wealth, passing along to Clarke 10% of the amount Russell was paid, which amounted

to about three dollars. This was Clarke's first stfnal income; Ghu alone knows

what would have happened if it was only one dollar. Why, Childhood's End

might have been written by Deutero Spartacus. Or Pel Torro. [ii]

Before

I get much further into this little laudatorium, I want to break with my usual

practice and step off the dais to talk about my own personal feelings about Russell

and his stories.

Long before I actually put pen to paper (yeah, I started

out that way—didn't we all?) for the express purpose of telling stories I

wouldn't get spanked for, I was reading pretty much everything I could find that

called itself "science fiction." At the library, if it had a rocket or atom on

the spine, it was mine, daddy-o, at least until it was due back. I honestly

don't recall at this far remove where I first encountered Eric Frank Russell's

work, but I can tell you when I first read it and said to myself, "I'm gonna do

this some day!"

It was an Ace Double, D-313 in fact, which put Russell's

The Space Willies back to back with a collection of six of his other stories,

Six Worlds Yonder. I read the A-side first, oddly enough (I was far more

accustomed to reading short stuff), and I don't think I put it down until Mom

had called me the third time for dinner. [iii]

I was absolutely delighted by this yarn about a smart-ass human using his imagination

to put one over on hide-bound aliens. So much so, in fact, that when I came to

write my first salable story, I had Willies and Eustaces very much in mind. It

sold, of course, to Analog, and I'd like to think that John Campbell would

have liked it, even if he wouldn't have bought it.

When I got to the B-Side,

I fell in love all over again with "Diabologic," and after reading "Into Your

Tent I'll Creep," it was more than a week before I could look my dog in the eye.

Is it any wonder I ended up writing for Analog a few decades after that?

I think not, Bubba. It was an inevitability, because that one Double influenced

my reading for a long, long time. It wasn't until Dangerous Visions came

along that I began to look elsewhere.

I learned a lot from reading Russell,

I did, even though it would be decades before I would put it to any real use.

I learned about pacing, characterization, and that humor on the page requires

exactly the same things that stand-up (well, in my case, class-clowning) does:

timing, delivery, wit, and a memorable punchline. I can point to others who influenced

me as well [iv]—Simak, Heinlein, Davidson,

Knight—but it was Russell who put me on the path to writing for Astounding—pardon

me, Analog.

But enough personal reminiscences. Let's get back to

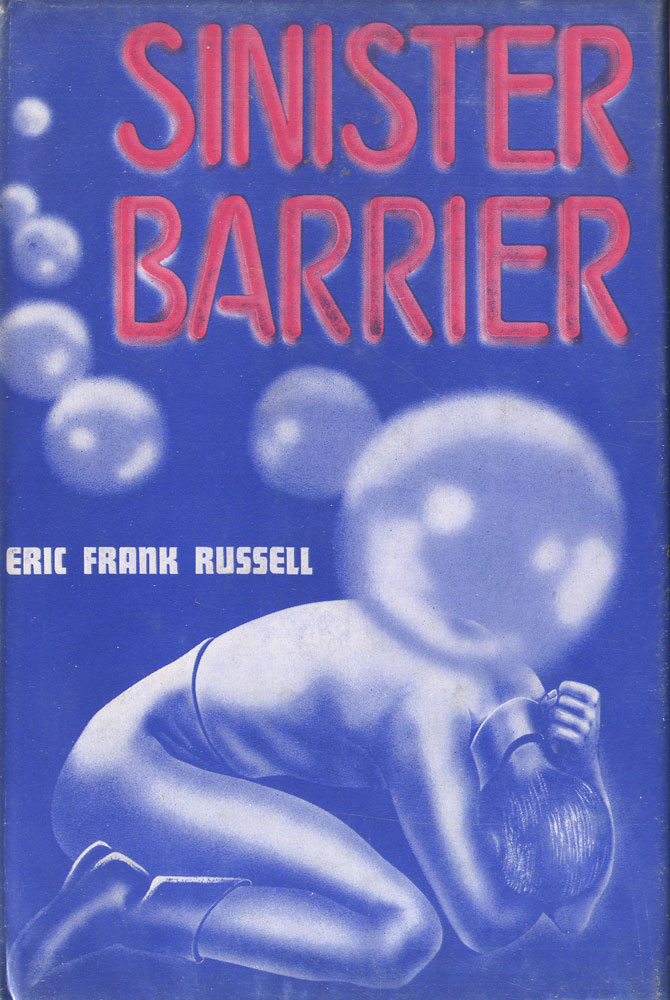

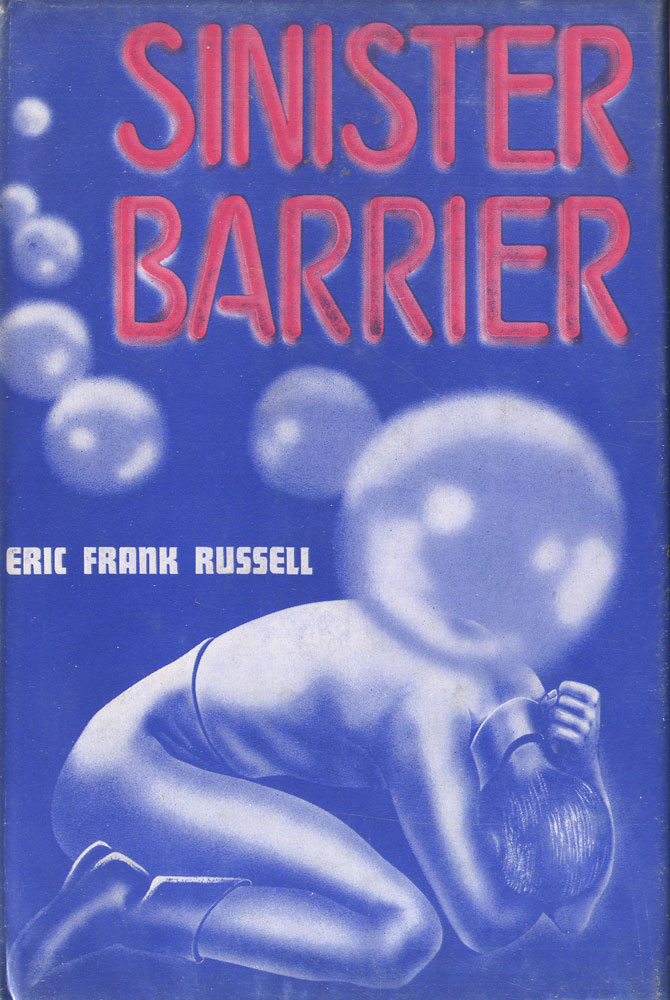

that legend I mentioned in the second paragraph, shall we? That magazine was Unknown,

later Unknown Worlds, and the first issue (March 1939) contained Russell's

justly famous "Sinister Barrier." Much has been said, both at the time and in

subsequent years, of the claim that Street & Smith's decision to launch a

new fantasy magazine as a companion to their very successful Astounding Stories

was predicated on finding the perfect place to publish Russell's "Sinister Barrier."

Stfnal legend tells us that Campbell, planning a fantasy magazine to go along

with his harder sf monthly, had an "AHA!" moment and pegged Unknown to

Russell's short novel.

Moskowitz, though, says this just isn't so. [v]

Writing about Russell in his important collection of authorial essays, Seekers

of Tomorrow (World 1967), he puts the whole thing up to coincidence, more

or less:

The origin of the magazine and the publication of the

novel seemed too happy a wedding to be fortuitous. Nevertheless, it was.

Seems

that Russell first submitted the story to Campbell in 1938 for Astounding

under the title "Forbidden Acres." Campbell loved the first half but not the second,

and sent it back to Russell for a rewrite. SaM continues:

Russell

. . . decided to rewrite the novel from end to end, utilizing as his technical

model the Dan Fowler stories which ran in G-Men, a popular pulp magazine

of the period. Campbell, on accepting the revision, openly admitted he was astonished

that Russell, with his limited writing experience, had been able to do the difficult

theme justice.

We'll get to that theme in a few, but first

I want to add one vote in favor of legend, if I may. In the first volume of his

two-volume autobiography, In Memory Yet Green (Doubleday 1979), Isaac Asimov

writes of meeting Russell at a meeting of the Queens Science Fiction League in

'39:

Unknown was a magazine the like of which had never

appeared before. . . . Campbell had conceived of it precisely as a vehicle for

Sinister Barriers [sic]. . . .

Well, I'm sure the Good

Doctor meant well [vi], but the fact is that

I can find no real confirmation that the above is the case, and a look at the

foreword to the 1948 Fantasy Press edition of the full novel puts, I firmly believe,

the final kibosh on the legend (much as I'd have loved it to be true). In dedicating

the book in part to Campbell, Russell says ". . . for kicking me around until

this story bore more resemblance to a story." Add to this the fact that, although

there is a letter to Russell in The John W. Campbell Letters Volume 1 (edited

and compiled by Perry A. Chapdelaine, Sr., Tony Chapdelaine, and George Hay, AC

Projects 1985), it dates from 1952; there is no mention of the story or its having

been a factor in the creation and publication of Unknown, just a long argument

with Russell about Charles Fort. And finally, Alan Dean Foster, in his glowing

and laudatory introduction to The Best of Eric Frank Russell (Ballantine/Del

Rey 1978), never once mentions it even as a legend. QED, I think we can put this

one to bed.

Which leads us, William Nilliam, to the basic premise of this

justly famous novel: we are property. Cows, if you will. Don't worry, I'll explain.

Charles

Fort was a popular force in the late 19-teens through his death in 1932. He was

heatedly debated, both in the field of science fiction and the Real World, and

his "conclusions" were targets of both derision and reverence. This is not the

place to delve too deeply into his "theories," but the Wikipedia entry under his

name is both informative and, given the vagaries of both format and subject, reasonably

accurate.

To put it concisely, Fort compiled odd-ball news stories, what

newspaper folk refer to as "silly season" items: rains of fish and/or frogs, people

disappearing without explanation, that sort of thing. I suspect he didn't really

believe most of what he gleefully presented to an eager readership, but just enjoyed

screwing with peoples' minds.

One thing he said, though, not only rang true

with Russell, but Edmund Hamilton and several other authors in and out of the

field (although Russell certainly got more mileage than most). As Russell said

in the intro to the Fantasy Press edition:

Charles Fort gave me

what might well be the answer. . . . Casually but devastatingly, he said, " I

think we're property." [Italics Russell's] And that is the plot of Sinister

Barrier.

More specifically, we are the property of an

unseen (unseeable?) alien race that keeps us in an uproar, prevents a long-lasting

peace, and in essence breeds us like cattle. For much the same reason we breed

cattle, too.

I honestly don't know how much of Fort's blather Russell actually

believed, either, but he was a long-time member of the Fortean Society, and I

think it’s reasonable to believe that he wasn't just in it for the plot ideas.

All

that to give you a background for this very fine novel, and thanks for sticking

around. Sinister Barrier begins, more or less, with those cows I mentioned

a while ago in the form of a quote from one Peder Bjornson, a professor with funny

eyes: "Swift death awaits the first cow that leads a revolt against milking,"

he says. Dunno about you, but it hooked me right away.

Seems that a lot

of his fellow profs, all of whom have funny eyes [vii],

have been dropping like, well, pole-axed steers. An investigator, one Bill Graham

(and didn't I get a kick out of that name in my Fillmore days), is sent

to look into the deaths—he even witnesses one early on—and what he finds

would have Charles Fort nodding his head up and down frantically and yelling,

"See? See, I told you!" There is much ensuing paranoia involving iridescent

blue globes flying about feeding off peoples' emotions, causing wars and strife

so that their à la carte menu will have plenty of daily specials, desserts

and those amber beverages we're all so fond of [viii].

This

is perhaps the best known of his novels, and deservedly so, but there's another

book I constantly and consistently saw in the used bookshops [ix]

I used to haunt that's almost as well-known, if not more famous. That book, one

of my own all-time favorites, is Men, Martians and Machines. A collection

of stories about a man/robot named Jay Score (J20 in his robotic persona), this

was not only my first introduction to aliens and humans working together (predating

Star Trek by most of a decade), but also the first time to my knowledge that an

African-American had been featured as ship's crewman (in this case the doctor).

There was a reason for this in Russell's plot-line—apparently, no Negroes

(as was then the respectful term) ever got space sick. Don't forget this was the

early '40s, a time when the depiction of African-Americans in popular culture

was still less than courteous, and an African-American as a serious character

who did nothing in the way of either shucking or jiving was rare indeed, not to

mention pretty cool. I don't necessarily think that Russell was trying to make

a major point, or to showcase his (comparative) broad-mindedness; I just don't

think he felt that a Negro had to be portrayed as a Steppin Fetchit caricature

instead of a reasonable human being. If this be Libertarianism (or—say it

softly!—Liberalism), then so be it.

Jay Score is a big, quiet man in

the middle of a crew of characters who border on the wacky, and occasionally edge

all the way into zany. One might even call them madcap, if one were inclined to

do so. Most of them are human, but a few are Martians, and they're just as wacky/zany/madcap

as the regular folk are.

Don't get the idea that they're all that two-dimensional,

however. They're fun, and funny, but Russell's skill even in a series of yarns

tossed off to make John Campbell laugh is evident, and if they don't exactly leap

out of the story and dance around the room, they nevertheless work just fine on

the page. I especially like the Martians, haughty and sarcastic, playing chess

at every opportunity and complaining about the thick (to them) atmosphere, who

still manage to get their work done and act just as heroically in defense of their

non-tentacled shipmates as they do to protect themselves. Zany individuals the

crew and officers may be—this is Russell, after all—but they are first

and foremost a crew.

The book contains four stories, "Jay Score,"

"Mechanistra," "Symbiotica" and an original, "Mesmerica." I re-read this one at

least once a year, with as much delight and amusement as I got from it the first

time.

You shouldn't get the idea that Russell was all about cattle or provincial

aliens, either. Perhaps my favorite EFR story, one that still lumps up my throat

a little when I re-read it, is "Dear Devil" (May 1950 Other Worlds [x]).

I honestly don't know why Campbell didn't take this one—it's certainly ASF-worthy—and

I really don't know why Russell sent it to that most pulpish of the digests, Other

Worlds. Leaving aside for the moment that OW seems lost in the '30s,

the editor was none other than Ray Palmer, best known in the field for the Shaver

Mystery (isn't Google wonderful?) and "fact articles" about flying saucers. However

odd the match-up might seem at this remove, though, it was apparently just the

thing for EFR; "Dear Devil" was his first for Palmer, but indubitably not his

last. Perhaps the two men shared a Fortean connection. It's a definite possibility.

The

story itself is, my own teary opinion aside, one of Russell's best, and deservedly

one of his best-known. One could compare it to the famous axiom that clowns aspire

to serious roles, but that's just a little too easy for me to be comfortable with.

For all his puns and jokes and humor bordering on the bawdy—in Trillion

Year Spree, Brian Aldiss refers to him as "[Campbell's] licensed jester"—Russell

was no clown. His humor, broad as it may be, is satire (if not out-right parody),

frequently of the one major thing other than Forteanasticness that inspired him

to write: bureaucrats and the red-tape restraints which is their only reason for

existence. According to Russell, that is.

Here, though, the humor is gentle,

the satire moderated by honest sentiment. He chews no scenery, bangs no drums,

constructs no bopamagilvies. He gives us a Martian poet, not a soldier with a

steel rod up his fundament or a clever human ready to mess with said rod-butted

soldier. Already, I'm intrigued. How many exploratory missions would NASA make

with a poet onboard to "maintain morale by entertaining"?

The poet, Fander,

asks to be left behind when the captain decides that the third stone from the

Sun is dead and worthless. The captain reluctantly grants his request, and there

the story really begins.

Fander finds people, of course, hiding in the ruins,

"ragged, dirty, and no more than half grown." Children, almost feral, and almost

certainly doomed. Under less capable hands, we could already be moving into the

town square of Greater Maudlinity, but Russell is better than that.

"He

lay within the cave, a ropy, knotted thing of glowing blue with enormous, bee-like

eyes . . ." And tentacles, don't forget the tentacles. No wonder the first child

who sees him cowers from him, calling him "Devil! Devil!" Little by little, the

poet gains their trust by leaving food. Disaster is averted, not by massive Governmental

action or by military intervention, but by the simple acts of kindness shown by

this "Dear Devil" and the love and veneration shown him by his adopted charges.

What happens subsequently won't surprise anyone whose reading level is

somewhere north of Bambi, but that isn't the point. In many cases, the

greatest joy of the tour is not what you see as much as how the curator has arranged

it. Here, the title says it all. If you want to know more, track down a copy of

The Best of Eric Frank Russell or any other collection/anthology that contains

the story (go to William Contento's invaluable Index to Science Fiction Anthologies

and Collections, at http://www.philsp.com/homeville/ISFAC/0start.htm

to find out which ones). Trust me, how can you go wrong?

"Alamagoosa,"

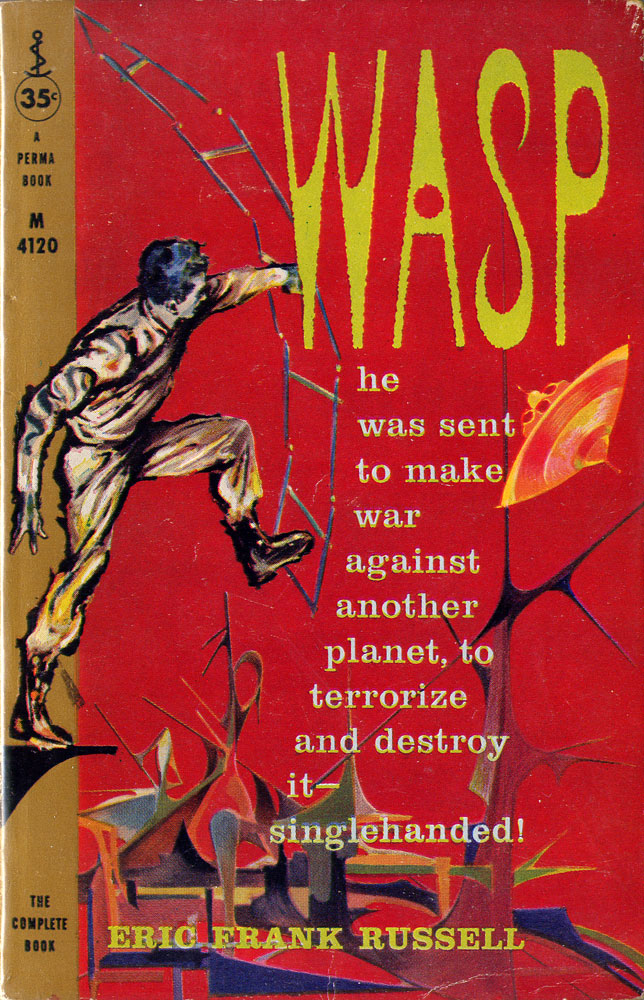

Deep Space, Wasp, "Homo Saps," "The Hobbyist". . . . Y'know what?

The truth, painful as it may be, is simple: I could go on for a lot longer than

I already have about Russell and his work, to the point that most of you reading

this would edge out of the room to escape. I make no apology for this—Russell

is a writer well worth going on and on about. But even though space on the Jim

Baen's Universe site is for all intents and purposes endless, I owe it to

my editors and you as well not to take a chance on running you off. Not to mention

what I may owe Eric Frank Russell himself. There are numerous copies of his books

out there to be had, either online or (preferably) at your local used bookshops

or convention dealers' rooms, so take a tip from ol' Budzilla his own self and

get into them. You'll have a good time, I promise.

"Alamagoosa,"

Deep Space, Wasp, "Homo Saps," "The Hobbyist". . . . Y'know what?

The truth, painful as it may be, is simple: I could go on for a lot longer than

I already have about Russell and his work, to the point that most of you reading

this would edge out of the room to escape. I make no apology for this—Russell

is a writer well worth going on and on about. But even though space on the Jim

Baen's Universe site is for all intents and purposes endless, I owe it to

my editors and you as well not to take a chance on running you off. Not to mention

what I may owe Eric Frank Russell himself. There are numerous copies of his books

out there to be had, either online or (preferably) at your local used bookshops

or convention dealers' rooms, so take a tip from ol' Budzilla his own self and

get into them. You'll have a good time, I promise.

[i] Yes, Virginia, there was an Astounding

editor before John Campbell. A couple, in fact: first, Harry Bates (of "Farewell

to the Master" fame; you'll remember it as "The Day the Earth Stood Still," and

I'm talking about the good one, youngster, not the recent crapola ) edited the

magazine for Clayton, then Tremaine came along when Street and Smith acquired

it in 1933.

[ii] Google Robert Lionel Fanthorpe, cowboy.

Interesting character.

[iii] If you've ever met me, you

know there's ample proof that I've been late for very few meals in my life.

This should tell you how engaged I was in this short novel, n'est-ce pas?

[iv] As opposed to those I wish I'd been influenced by,

including Cordwainer Smith, Harlan Ellison and Alfred Bester. Whew!

[v]

Although much earlier in his treatise on pre- and post-War fandom, The Immortal

Storm (ASFO Press, 1954), he apparently thought otherwise. In chapter XXXV

of this important book, he mentions Unknown ". . . which John W. Campbell

declared was being put out be [sic] Street & Smith solely because receipt

of a sensational novel by Eric Frank Russell called for creation of an entirely

new type of fantasy magazine." However, the gap of thirteen years between the

two books might account for this seeming disparity—and SaM didn't say in

the earlier book that he believed Campbell; he only reported what Campbell was

supposed to have said.

[vi] Dr. Asimov might have had

something of a blind spot where Unknown was concerned. In 1943, he sold

a short story titled "Author! Author!" to Campbell for the magazine, which folded

before it could be published. It was, in fact, the sixth story he had tried at

Unknown, and the only one Campbell had accepted. It didn't see print until

1964, when D. R. Bensen made it the lead in his second Pyramid anthology of stories

from the magazine, The Unknown Five, more than 20 years later.

[vii]

"Strangely protruding, strangely hard" it says here. No, really.

[viii]

Not me, though. I prefer my beer to be root.

[ix] Along

with Conklin's little hardcover-paperback, A Galaxy of Science Fiction,

raggedy-ass copies of The Martian Chronicles and stacks of The Andromeda

Strain.

[x] I find it interesting in a weird kind

of way that the cover date of this issue is the same cover date as the issue of

Astounding which contained L. Ron Hubbard's first article on Dianetics;

I wonder what Charles Fort would have made of this little juxtaposition. Coincidence?

I think not.

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ERIC FRANK RUSSELL

(As is

usually the case, although the list below is as complete as I can make it, I am

more than happy to stand corrected on errors or omissions. Contact me care of

this fine magazine and I'll fix it, and probably give you credit as well. I would

like to thank fellow bibliophile and scholar/historian Phil Stephensen-Payne (

http://www.philsp.com/pubindex.html#gcp)

for his enormous help in compiling the following bibliography. Huzzah,

Phil!)

Stories

"The Saga of Pelican West"—February

1937 Astounding

"The Great Radio Peril"—April 1937 Astounding

"The Prr-r-eet"—Winter 1937 Tales of Wonder, #1

"Seeker

of Tomorrow" (with Leslie J. Johnson)—July 1937 Astounding; Johnson's

name given as Leslie T.

"Mana"—December 1937 Astounding

"Egyptian Episode: The Rocket Plane and the Drug Traffickers"—11/37 Tales

of Crime and Punishment

"Poor Dead Fool"—January 1938 Thrilling

Detective (aka "Murder Without Motive")

"The World's Eighth Wonder"—Sum

1938 Tales of Wonder

"Impulse"—September 1938 Astounding (aka

"The Man From the Morgue" and "A Matter of Instinct")

"Shadow Man"—December

1938 Fantasy, #1 (aka "Invisible")

"Sinister Barrier"—March 1939

Unknown

"It's Hell to Be Shot"—Mystery Stories #15, 1939

"Vampire from the Void"—Fantasy #2, 1939

"Mightier Yet"—Fantasy

#3, 1939

"Me and My Shadow"—February 1940 Strange Stories

"I, Spy!"—Fall 1940 Tales of Wonder (aka "Venturer of the Martian

Mimics" and "Spiro")

"The Mechanical Mice"—January 1941 Astounding

(as by Maurice G. Hugi, a real writer; Russell ghost-wrote the story)

"Jay

Score"—May 1941 Astounding

"Seat of Oblivion"—November 1941

Astounding

"Homo Saps"—December 1941 (as by Webster Craig) Astounding

"With a Blunt Instrument"—December 1941 Unknown

"Mechanistria"—January

1942 Astounding

"Mr. Wisel's Secret"—February 1942 Amazing

(aka "Wisel")

"Describe a Circle"—March 1942 Astounding

"The Kid from Kalamazoo"—August 1942 Fantastic Adventures

"Symbiotica"—October

1943 Astounding

"Controller"—March 1944 Astounding

"Resonance"—July 1945 Astounding

"Metamorphosite"—December

1946 Astounding

"The Timid Tiger"—February 1947 Astounding

"Relic"—April 1947 Fantasy, The Magazine of Science Fiction (aka

"The Cosmic Relic")

"Hobbyist"—September 1947 Astounding

"Dreadful Sanctuary"—serial, June-August 1948 Astounding

"Displaced

Person"—September 1948 Weird Tales (vignette)

"Muten"—October

1948 Astounding (as by Duncan H. Munro)

"The Ponderer"—November

1948 Weird Tales

"Late Night Final"—December 1948 Astounding

"The Big Shot"—January 1949 Weird Tales

"A Present from

Joe"—February 1949 Astounding

"The Glass Eye"—March 1949

Astounding

"The Undecided"—April 1949 Astounding

"U-Turn"—April 1950 Astounding (as by Duncan H. Munro)

"Dear

Devil"—May 1950 Other Worlds

"Exposure"—July 1950 Astounding

"The Rhythm of the Rats"—July 1950 Weird Tales

"First Person

Singular"—October 1950 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Follower"—November

1950 Astounding

"MacHinery"—December 1950 Thrilling Wonder

Stories

"Test Piece"—March 1951 Other Worlds

"Afternoon

of a Fahn"—April 1951 Imagination (aka "Rainbow's End")

". .

. And Then There Were None"—June 1951 Astounding (aka "Talisman")

"The Witness"—September 1951 Other Worlds

"Ultima Thule"—October

1951 Astounding

"The Illusionaries"—November 1951 Planet Stories

"The Star Watchers"—November 1951 Startling Stories

"The

Big Dark"—January 1952 World Youth

"Second Genesis"—January

1952 Blue Book Magazine

"I'm a Stranger Here Myself"—March 1952

Other Worlds

"Fast Falls the Eventide"—May 1952 Astounding

"Take a Seat"—May 1952 Startling Stories (vignette)

"Dreamers

of Space"—June 1952 World Youth

"I Am Nothing"—July 1952

Astounding

"Hell's Bells"—July 1952 Weird Tales (as by

Duncan H. Munro; originally in March 1945 Short Stories, as "Bentley's

Old London Djinn"; slightly modified for Weird Tales)

"The Sin of

Hyacinth Peuch"—Fall 1952 Fantastic

"A Little Oil . . ."—October

1952 Galaxy

"Last Blast"—November 1952 Astounding

"The Timeless Ones"—November 1952 Science Fiction Quarterly

"Design

for Great-Day"—January 1953 Planet Stories (aka "The Ultimate Invader")

"Somewhere a Voice"—January 1953 Other Worlds

"When the

Sun Goes Down: A Fantasy of the `Dark Ones'"—serial, April-June 1953 World

Youth

"It's in the Blood"—June/July 1953 Fantastic Universe

"This One's on Me"—Nebula #4, 1953

"A Great Deal of Power"—August/September

1953 Fantastic Universe (aka "Boomerang")

"Postscript"—October

1953 Science Fiction Plus (aka "P.S.")

"Bitter End"—December

1953 Science Fiction Plus

"Sustained Pressure"—Nebula

#6, December 1953

"Appointment at Noon"—March 1954 Amazing

"The Door"—March 1954 Universe

"Fly Away Peter"—April 1954

Nebula, #8

"Anything to Declare?"—April 1954 Fantastic

(as by Naille Wilde)

"Weak Spot"—May 1954 Astounding

"I

Hear You Calling"—November 1954 Science-Fantasy, #11

"The Courtship

of 53 SHOTL 9 G"—December 1954 Fantastic (as by Naill Wilde)

"Mesmerica"—in Men, Martians and Machines, q.v.

"Nothing New"—January

1955 Astounding

"Diabologic"—March 1955 Astounding

"Allamagoosa"—May 1955 Astounding

"Tieline"—July 1955 Astounding

(as by Duncan H. Munro)

"Proof"—July 1955 Fantastic Universe

"Saraband in C Sharp Major"—July 1955 Science Fiction Stories

"The Waitabits"—July 1955 Astounding

"Call Him Dead"—serial,

August-October 1955 Astounding

"Heart's Desire"—September 1955

Science-Fantasy, #16 (contents page reads "Niall Wilde", story byline is

"Nigel Wilde")(aka "A Divvil With the Women")

"Down, Rover, Down"—November

1955 Nebula, #14 (aka "The Case for Earth")

"Minor Ingredient"—March

1956 Astounding

"Legwork"—April 1956 Astounding

"Sole

Solution"—April 1956 Fantastic Universe (vignette)

"Run, Little

Men!"—June 1956 Famous Detective Stories

"Plus X"—June 1956

Astounding

"Storm Warning"—July 1956 Nebula, #17

"Top Secret"—August 1956 Astounding

"Quiz Game"—September

1956 Fantastic Universe

"Fall Guy"—November 1956 Fantastic

Universe

"Heav'n, Heav'n"—September 1956 Future, #30

"Nuisance Value"—January 1957 Astounding

"Love Story"—August

1957 Astounding

"Into Your Tent I'll Creep"—September 1957 Astounding

"Early Bird"—November 1957 Science Fiction Stories

"Brute

Farce"—February 1958 Astounding

"Wasp"—serial, March-May

1958, New Worlds

"Basic Right"—April 1958 Astounding

"There's Always Tomorrow"—June 1958 Fantastic Universe

"Study

in Still Life"—January 1959 Astounding (aka "Still Life")

"Now

Inhale"—April 1959 Astounding

"The Army Comes to Venus"—May

1959 Fantastic Universe (reprint of "Sustained Pressure")

"Panic Button"—November

1959 Astounding

"Meeting on Kangshan"—March 1965 If

"Eternal Rediffusion" (with Leslie J. Johnson)—Harbottle Fantasy Booklet

#3 1973 Articles

"Over the Border"—September 1939

Unknown

"Spontaneous Frogation"—July 1940 Unknown

"Asstronomy"—July 1955 New Worlds

"And Still It Moves"—June

1957 Astounding

"The Creeping Coffins of Barbados"—in Great

World Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"The Riddle of Levitation"—in Great

World Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"Satan's Footprints"—in Great World

Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"The Ship that Vanished"—in Great World

Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"The Case of the `Mary Celeste'"—in Great

World Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"The Child of Nuremburg"—in Great

World Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"Gadgets in the Sky"—in Great World

Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"The Last of the Long-Ears"—in Great World

Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"Ordeal by Fire"—in Great World Mysteries,

Dobson 1957

"The Riddle of Levitation—in Great World Mysteries,

Dobson 1957 as

"The Mystery of Levitation" in Great World Mysteries

"Sea Monsters"—in Great World Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"The

Ship that Vanished—in Great World Mysteries, Dobson 1957 as

"The

Loss of the Waratah" in Great World Mysteries

"Stargazers—January

1959 Amazing, revision of "Asstronomy"

"The Vanishing Courier"—in

Great World Mysteries, Dobson 1957

"Stargazers"—January 1959

Amazing

". . . And Who the Pot?"—June 1959 Amazing

"A Many Legged Thing"—November 1959 Fantastic Universe

"A Trench

and Two Holes"—November 1960 New Worlds (guest editorial) Novels

and Collections

Sinister Barrier—World's Work 1943 (UK);

Fantasy Press 1948 (expanded from Unknown appearance); Galaxy Novel 1,

1950

Dreadful Sanctuary—Fantasy Press 1951; Lancer 74-819, 1963

Sentinels from Space—Bourgey & Curl 1953; Ace Double D-44

(as Sentinels of Space, bound with The Ultimate Invader, ed. Donald

Wollheim; Ace D-468, 1961)

Deep Space—Fantasy Press 1954; Bantam

1362, 1955

Men, Martians and Machines—Dobson 1955 (UK); Roy 1956;

Berkley G148, 1958 (collection)

Three to Conquer—Avalon 1956;

Ace Double D-215 (bound with Robert Moore Williams's Doomsday Eve)

Wasp—Avalon 1957; Perma Books M4120, 1959

The Space Willies—Ace

Double D-315 (bound with his Six Worlds Yonder); Dobson 1959 UK) as Next

of Kin

Six Worlds Yonder—Ace Double D-315 (bound with his

The Space Willies) (collection)

Far Stars—Dobson 1961

(UK); Panther 1691, 1962; Goldmann 1962 (collection)

The Great Explosion—Dobson

1962 (UK); Torquil 1962; Pyramid F862

Dark Tides—Dobson 1962

(UK); Panther 1599, 1962 (UK)

With a Strange Device—Dobson 1964

(UK); Penguin 2358, 1965 (UK); Lancer 72-942, 1965 (as The Mind Warpers)

Somewhere a Voice—Dobson 1965 (UK); Ace F-398, 1966 (collection)

Like Nothing On Earth—Dobson 1975 (UK); Methuen , 1986 (collection)

The Best of Eric Frank Russell—Ballantine 0345277007, 1978

Next of Kin—Ballantine 345-32761-6, 1986

Design for Great-Day

(with Alan Dean Foster)—Tor 1995

Major Ingredients: The Selected

Short Fiction of Eric Frank Russell—NESFA Press 2000 (collection)

Entities: The Selected Novels of Eric Frank Russell—NESFA Press 2001

Darker Tides: The Weird Tales of Eric Frank Russell—Midnight

House 2006] Non-Fiction Books

Great World Mysteries—Dobson

1957

The Rabble Rousers—Regency Books RB317, 1963

The

ABZ of Scouse—Scouse Press, 1966 (as by Linacre Lane)

Back

to index

"Fiddle around," he says. Would that we all could "fiddle around" as well. Russell

may have been ironically self-effacing up there, but the fact is he wrote a lot

of terrific stories, including one that was so good, legend has it, that John

W. Campbell had to create a magazine to fit around it. I'll get to that a little

later, though.

"Fiddle around," he says. Would that we all could "fiddle around" as well. Russell

may have been ironically self-effacing up there, but the fact is he wrote a lot

of terrific stories, including one that was so good, legend has it, that John

W. Campbell had to create a magazine to fit around it. I'll get to that a little

later, though.