| "Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline,

high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull,

and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an

entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science

past and present, with all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government--which,

however, already has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and

you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man." --

Nayland Smith to Dr. Petrie, Sax Rohmer quite consciously created Dr. Fu Manchu as "the yellow peril incarnate in one man." But where did the Devil Doctor come from?Rohmer, himself, gave a number of accounts, not entirely consistent, regarding how "Fu Manchu" came to be. Cay Van Ash and Elizabeth Sax Rohmer provide an account of the "Limehouse Incident" in Master of Villainy, A Biography of Sax Rohmer. Rohmer explained "The Birth of Fu Manchu" in the Daily Sketch of May 24, 1934, again in "The Birth of Fu Manchu," in the "Pipe Dreams" series of articles in the Empire News January 30, 1938, and yet again in "How Fu Manchu Was Born" in This Week, September 29, 1957. All are various accounts of how he was inspired to create Dr. Fu Manchu by a mysterious "Mr. King."The Mr. King saga has been repeated by many fans and writers, and it is generally accepted to have occurred and played some role in the creation of Fu Manchu. In the Dover (1997) edition of The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu, for example, Douglas G. Greene writes "Rohmer based Fu-Manchu on vague stories about a man he had never met." Greene goes on to relate his version of the "Mr. King" story and looks no deeper into what might have influenced Rohmer. A succinct summary of the incident, in the context of the "yellow peril," is found in the Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection:

The Boxer Rebellion provides an interesting context for Fu Manchu and his organization, the Si-Fan. The rebellion was essentially a terrorist movement by the Chinese people to rid China of foreigners and foreign influence. It resulted from the increasingly distasteful attitudes and actions of the British and other foreign powers. China was totally in the control of the Western nations and the culture and religions of the Chinese were ignored or mocked. As it became clear that the Chinese were fighting to expel the foreigners, many assumed they would become aggressive and expansionist and seek to invade or otherwise gain control of the West -- as the West had done to them. Many popular writers explored the possibility of such a turn of events and Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu certainly responded to these fears.It should also be noted that while Rohmer's fictional creation responded to popular conceptions and stereotypes of his day, the character did not represent his personal views. As noted above, in 1938 Rohmer published an essay in The Manchester Empire News. This version of the creation of Fu Manchu is perhaps the most revealing because he delays the telling of the "Mr. King" story until he refutes Bret Harte and other Westerners who believe the stereotype and offers his personal beliefs. He explains that the Chinese penchant for "honesty" may be why Westerners find them "mysterious." He illustrates the total ignorance of typical Westerners with the following anecdote: "As an old lady on a world cruise, who had had a glimpse of the Great Wall of China, confided to me: 'It’s dreadfully out of repair!'" He later observes: "I have a great respect for the Chinese. As a nation they possess that elusive thing, poise, which I sometimes think we are losing." He did, however, recognize the appeal of a fictional character who would respond to popular sterotypes.The "yellow peril" provided a broad popular mindset and context. And Rohmer's account of inspiration in Chinatown is interesting and appropriately mysterious. It is curious, however, that Rohmer never acknowledges an inspiration, an influence or a model in anything he read. The "Mr. King" and Limehouse influences would lead the reader to believe that Rohmer created Fu Manchu of whole cloth, with no influence from earlier writers -- or as a heading in "The Birth of Fu Manchu" would have it: "He Just Happened."In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (1978), Donald H. Tuck notes that "Rohmer had qualities lacking in most suspense and thriller writers: a thorough and first hand knowledge of exotic backgrounds, a flair for vivid description, and a sense of atmosphere, of magic and mystery. He applied his unfettered imagination not only to his fiction but to his personal publicity--interviews, biographical sketches, etc. As a result it is difficult to separate fact from fancy, and many details of his early personal life are obscure." John Harwood ("Speculations on the Origin of Dr. Fu Manchu," The Rohmer Review No. 2, January 1969) acknowledges the influence of Mr. King, but he also asks:

Harwood then outlines a very plausible theory that Rohmer was influenced by news of Hanoi Shan, a powerful Chinese official who, following a crippling accident, went to France to seek medical attention. Bitter in his disappointment in finding help, he disappeared from sight, later to emerge as head of a criminal organization that included "Apaches from the Paris underworld as well as some of the most vicious criminals of the Orient." His height of power and news worthiness was 1906 to 1908 and Harwood notes that "Sax Rohmer would have been able to read of the crimes either in the newspapers or in the official records several years before publication of his first Fu Manchu story." |

|

|

If Sax Rohmer might have read of Hanoi Shan, what else might he have read in London or while traveling on the continent at the turn of the century -- before seeing Mr. King in Limehouse or writing The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu?Seeing Mr. King may have been the spark, but what was the mix? Whether conscious or unconscious, it is more than possible that he read one or more books in his areas of interest that predisposed or influenced him as he created Dr. Fu Manchu and sought to establish his own presence in popular literature.What might those books have been? |

The list below is limited to books published prior to 1911. While the book, The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu, was published in June of 1913, the first Fu-Manchu story, "The Zayat Kiss," was published in the October 1912 issue of The Story-Teller, and Rohmer apparently began writing the story sometime in 1911.All this speculation would be unnecessary if we had a list of the books in his personal library such as the catalog of M. P. Shiel's books contained in Morse's The Works of M. P. Shiel (1948). Unfortunately we don't, so let's speculate. |

|

Selected Yellow Peril - Master Criminal Books Published

|

|

Possible PrecursorsSax Rohmer certainly had the opportunity to read any book on the list above, but we have no means of knowing if he, in fact, did. But if he read them which most clearly foreshadowed key elements of The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu?Rohmer must surely have been aware of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Moriarty, but there are two additional authors, curiously both Australian, who created characters who appear to present major elements of Dr. Fu-Manchu's personality, family and penchant for the exotic before Dr Fu Manchu, himself, was conceived: Guy Boothby's Dr. Nikola and Albert Dorrington's Dr. Tsarka. |

|

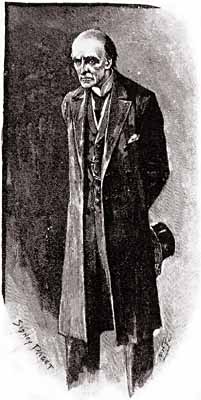

Prof. Moriarty |

|

| He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organizer of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order. He sits motionless, like a spider in the centre of its web, but that web has a thousand radiations, and he knows well every quiver of each of them. He does little himself. He only plans.But his agents are numerous and splendidly organized. Is there a crime to be done, a paper to be abstracted, we will say, a house to be rifled, a manto be removed -- the word is passed to the professor, the matter is organized and carried out. The agent may be caught. In that case money is found for his bail or his defence. But the central power which uses the agent is never caught --never so much as suspected. This was the organization which I deduced, Watson, and which I devoted my whole energy to exposing and breaking up. -- Sherlock Holmes "The Final Problem" |

|

In a two part article entitled "The Long Shadow of Moriarty," (Sherlock Holmes: The Detective Magazine, 29, 30, 1999) Paul M. Chapman makes the case that while not the first great criminal genius in English literature, Moriarty "was the precursor of the early twentieth century trend towards all-encompassing super-criminals." While the "yellow peril" element is notably absent, there are a number of elements that relate closely to Dr. Fu Manchu.First, the passage above clearly foreshadows Dr. Fu Manchu's secret society, the Si Fan. Fu Manchu's agents, including his Dacoits, are also numerous and splendidly organized. Then there is the physical appearance. Doyle tells us Moriarty is "extremely tall and thin, his forehead domes out in a white curve, and his two eyes are deeply sunken in his head. He is clean-shaven, pale, and ascetic-looking, retaining something of the professor in his features. His shoulders are rounded from much study, and his face protrudes forward and is forever slowly oscillating from side to side in a curiously reptilian fashion." It is interesting that upon confronting Holmes, Moriarty's first statement is "You have less frontal development than I should have expected." Sidney Paget's classic portrait in The Strand clearly shows Moriarty's massive Shakespearian brow.We might also compare Prof. Moriarty's "curiously reptilian" movements with Dr. Fu Manchu's "abnormal eyes, filmed and green." Dr. Petrie actually reported a third eyelid which made him "think of the membrana nictitans in a bird." In "The Third Eyelid" (Rohmer Review # 14) Marvin L. Morrison explored the biological possibility and consequent advantages of such a membrane--notably Fu Manchu's ability to have "instantaneous night vision" allowing his many sudden disappearances when lights went out.And finally there is the matter of education and intellectual achievements. Both Moriarty and Fu Manchu are noted for their superior intelligence and education. Moriarty is "a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker [with] a brain of the first order" who also had an "excellent education" and was a college professor at an early age. Dr. Fu Manchu, Rohmer tells us, is "unquestionably, the most malign and formidable personality existing in the known world today. He is a linguist who speaks with almost equal facility in any of the civilized languages, and in most of the barbaric. He is an adept in all the arts and sciences which a great university could teach him. He also is an adept in certain obscure arts and sciences which no university of to-day can teach. He has the brains of any three men of genius. Petrie, he is a mental giant."While the noted similarities are clear, they are generic. The "yellow peril" element so central in the character of Fu Manchu and the threat he represents is absent. For that, we must look elsewhere. |

|

Dr. NikolaIn The Art of Mystery & Detection Stories, Peter Haining describes Guy Boothby as "one of the most unjustly neglected crime and mystery authors of the turn of the century. If any one character might have influenced Rohmer's blending of a super-criminal and the "yellow peril," it would be Boothby's Dr. Nikola, introduced in 1895 in A Bid For Fortune. This was the first of five Dr. Nikola novels. The action moves from Australia through Europe to London and Port Said back to Australia. Dr. Nikola is described physically early in the tale. |

|

|

It would take more time than I can spare the subject to give you an adequate and inclusive description of the man who entered the room at that moment. In stature he was slightly above the middle height, his shoulders were broad, his limbs perfectly shaped and plainly muscular, but very slim. His head, which was magnificently set upon his shoulders, was adorned with a profusion of glossy black hair; his face was destitute of beard or moustache, and was of oval shape and handsome moulding; while his skin was of a dark olive hue, a colour which harmonized well with his piercing black eyes and hair. His hands and feet were small, and the greatest dandy must have admitted that he was irreproachably dressed, with a neatness that almost bordered on the puritanical. In age he might have been anything from eight-and-twenty to forty; in reality he was thirty-three.(pp. 7-8) |

This description can profitably be compared to Rohmer classic description of Fu Manchu. Dr. Nikola's "scientific" interests and his arsenal might easily be taken as a description of one of Fu Manchu's own haunts. |

|

| To begin with, round the walls were arranged, at regular intervals, more than a dozen enormous bottles, each of which contained what looked, to me, only too much like human specimens pickled in some light-coloured fluid resembling spirits of wine. Between these gigantic but more than horrible receptacles were numberless smaller ones holding other and even more dreadful remains; while on pedestals and stands, bolt upright and reclining, were skeletons of men, monkeys, and quite a hundred sorts of animals. The intervening spaces were filled with skulls, bones, and the apparatus for every kind of murder known to the fertile brain of man. There were European rifles, revolvers, bayonets, and swords; Italian stilettos, Turkish scimitars, Greek knives, Central African spears and poisoned arrows, Zulu knob-kerries, Afghan yataghans, Malay krises, Sumatra blow-pipes, Chinese dirks, New Guinea head catching instruments, Australian spears and boomerangs, Polynesian stone hatchets, and numerous other weapons the names of which I cannot now remember. Mixed up with them were implements for every sort of wizardry known to the superstitious; from English love charms to African Obi sticks, from spiritualistic planchettes to the most horrible of Fijian death potions. (pp.160-161) | |

And finally the global span of his reputation and sphere of influence might just as well describe Fu Manchu. |

|

| " ' Who is this Nikola, then?' I asked. " ' Dr. Nikola! Well, he's Nikola, and that's all I can tell you. If you're a wise man you'll want to know no more. Ask the Chinese mothers nursing their almond-eyed spawn in Peking who he is. Ask the Japanese, ask the Malays, the Hindoos, the Burmese, the coal porter in Port Said, the Buddhist priests of Ceylon; ask the King of Corea, the men up in Tibet, the Spanish priests in Manila or the Sultans of Borneo, the Ministers of Siam, or the French in Saigon. They'll all know Dr. Nikola and his cat, and take my word for it, they fear him.' (275) |

|

The cat, a large "fiendish black cat," with the habit of sitting on Dr. Nikola's shoulder immediately brings to mind Fu Manchu's marmoset. Throw in the quest for immortality, a two foot eight inch albino dwarf, a Burmese monkey boy, assorted other exotic creatures, an uncanny ability with hypnosis, abductions, poisonings, and an international network of minions and you get a world very much like Dr. Fu Manchu's. |

|

The five Dr. Nikola novels:

All were widely available in London in the years preceding the birth of Fu Manchu. |

|

Dr. TsarkaWhile it doesn't attain the similarities in atmosphere of the Boothby novels, Albert Dorrington's Dr. Tsarka does foreshadow a number of Fu Manchu's qualities. Dr. Tzarka appeared in just one novel, The Radium Terrors published in 1910. He is a Japanese doctor and scientist who uses his superior intellect to gain enormous wealth at the expense of "the rich of England and America," or as he justifies his actions: "In the name of Reason and Justice I have brought the weapon of science to bear upon the beast of sloth -- the idle rich and the leering aristocrat" (99).Dr. Tsarka's scheme involves a Japanese artist whose art works contain Dr. Tsarka's mechanisms for exposing patrons' eyes to radium and consequent blindness. The only hope for their vision is a cure by Beatrice Messonier, a young female British doctor who charges enormous fees at her Messonier Institute -- secretly controlled by Dr. Tsarka, who is described early in the novel. |

|

|

|

The "capacious brow" quite naturally brings to mind Fu Manchu's "brow like Shakespeare." Dr. Tzarka, while capable of horrible deeds, is also known to keep his word. He blinds and disfigures his partner by pouring molten metal on his face. He blinds people with radium and has no regard for those less fortunate than the aristocrats who can afford the fees. Yet he keeps his word.Two other aspects of the novel are echoed by Rohmer. Tsarka has a beautiful daughter, Pepio, who, much as Dr. Fu Manchu's daughter, does not always agree with her father and, on occasion, actually helps the hero, young British detective Gifford Renwick -- as when she secretly gives him the money to pay for his cure after he is blinded by radium. In addition to his various scientific mechanisms and formulas, Tsarka also uses Kezzio, an intelligent white rat from Nagasaki, to commit crimes. Kezzio, too, would be quite at home in Fu Manchu's company.Dr. Tsarka is no Fu Manchu, but if Rohmer had read the novel or been familiar with it, he might have used these elements, consciously or not, when fleshing out Fu Manchu. |

|

We have no way of knowing with certainty that Sax Rohmer even knew of the existence of these books, let alone read them. But the possibility is intriguing. As Cay Van Ash said while speculating about the origin of Sax Rohmer's name: "Of course, this is all just theorizing---but theorizing of the sort in which Sax Rohmer himself took delight, so I make no apology for it." |

|