from Rotarian

Strike Your Average -- Early!

by Ellis Parker Butler

My family and I spent last summer at a small lake in the Berkshire Hills where we rented a modest shack for the season. I don't mind saying that it cost us considerably less than we would have had to pay if we had rented the Ritz-Carlton for the same period. I got quite a little work done during the days there, and in the early evenings I did quite a bit of fishing that would list as something like Grade 9 or lower, but the shack was located in what people usually speak of as "around at the other end of the lake," and you know what that means. We were blessedly distant from the area of deep-tangled wildwood where, if Papa Jones sticks his foot out of bed during the night it goes out of the window and into the next cottage and hits Papa Smith in the face. I liked the remoteness. I don't really care to go forth into the heart of Nature and spend nine weeks in a cottage that overlaps the next one like a sweetie sitting on her honey-boy's lap. My idea of a satisfactory wilderness is not one where the cottages are so close together that when Mr. Miffis sits down on the edge of his bed and takes off his left shoe and drops it, all the people in the adjacent eighteen cottages quiver and hold their breaths until he has dropped the other shoe. In such far-from-the-madding-crowd places a one-legged man can give the whole gang of nature-seekers nervous prostration in two weeks. His other shoe never drops.

But, after dinner in the evening, in a shack "around at the other end of the lake," as ours was, there is apt to be considerable time between sunset and the hour when a man can go to bed without feeling ashamed of himself. He can, of course, sit on the porch and converse with his family. Then the conversation is apt to run like this:

"Is that a frog?"

"Yes, I think that is a frog."

"It sounds loud for a frog."

"Yes, it is probably a big frog."

"Well, I think I'll go to bed."

On other nights, when there are no frogs singing their love-songs, the conversation may not refer to frogs. It will then run like this:

"Is that a light over there?"

"Yes, it looks like a light."

"I don't think there is a cottage over there."

"No, it's probably on a boat."

"Well, I think I'll go to bed."

It may, however, be raining and no one is out in a boat and the frogs are drowned in silence. This does not necessarily do away with conversation on the porch of the cottage. The talk will then take this slant:

"I did not get the laundry today."

"Well, I have plenty of shirts left."

"If it stops raining I'll get the laundry tomorrow."

"Yes; that's all right."

"Well, I think I'll go to bed."

Ten minutes later it is so cold that one goes inside. Everyone else is in bed. One then looks at the books on the shelf and is sorry he has already read all of them twice. At this point, last summer, I took a pack of cards and seating myself gracefully at the table, began to play solitaire. Sometimes I played until midnight, sometimes until one o'clock in the morning; sometimes I only played until my feet got so cold and brittle that I was afraid to wiggle my toes. Then I undressed and went to bed, walking on my heels and taking care not to knock my toes against the chairs. In one stretch of evenings last summer up there in the Berkshires I played four hundred and ninety-six hands of solitaire at forty-two sittings. Some of these sittings were in the afternoon while waiting for dinner, but most were at night. I know a dozen or more good solitaire games, one pack and two pack, and I have books containing one hundred and thirty-four different games, but in this long run of four hundred and ninety-six hands I played one game exclusively. I played it so long and faithfully that when I quit my daughter said to my wife, "Has papa quit playing that game? Thank goodness! It made me feel as if he were going crazy."

The game I played was one form of the game known as Canfield. It is one of the simplest solitaires and one of the best one-pack games. Of one form of this game it is said that it gained notoriety through having been used as a game in the famous gambling establishment once run by the man whose name the game now bears. As played there, it is said, the patron bought a new pack of cards from Canfield for fifty-two dollars -- a dollar a card; Canfield then paid the player five dollars for each card he could "get out."

There is no use in giving the rules here. It is enough to say that as the aces appear they are put on the table. The game is to build up on these aces, a two on an ace, a three on a two, spades on spades, diamonds on diamonds, and so on. It is clear that if a patron paid fifty-two dollars for a pack of fifty-two cards and then "got out," being able to play the entire fifty-two cards, he would be paid five dollars for each card, which is five times fifty-two, or two hundred and sixty dollars. As he had paid fifty-two dollars for the cards his profit would be two hundred and eight dollars. Canfield would lose that much.

But right there is where the trick comes in; it is not so easy to "get out." A person may play and play, hand after hand, and not get out. One time he may get out four cards, the next time seven, the next time forty and the next only one or none at all. One thing seemed to be pretty sure and that was that Canfield would not have let his patrons play this game unless he had a slight percentage, at least, in his favor. Out of what he won from his patrons he had to pay for rent or taxes, light, heat, employees, and sundries. The professional gambler, or manager of a gambling house, must have the percentage in his favor or he can't exist.

On the other hand the patron of the gambling house must have what he believes is a fair chance of winning once in awhile. If he loses every time he will not play. This is one thing the gambler realizes; the patron must have the bait for an occasional winning to keep him coming to the bait like a real sucker. For this reason, before a gambling house owner introduces a new game to his patrons, he must -- I am sure -- have some expert player play that game again and again, possibly thousands of times, and keep a record of how the game runs. Presently, by thus keeping track, a schedule of averages is built up and the gambler knows pretty well what he can afford to do. He demands that he be a sure winner in the long run, but he wants to let his victim win often enough to continue to have hope. Foolish hopes have wrecked more people than sane despair.

Up there in the Berkshires on those chilly nights I did not play the game of Canfield exactly as it was played in Canfield's establishment in the days when that establishment was in existence. I played a variation of it. Neither was I trying especially to see whether Canfield would win or lose or how much.

I had been playing the game more or less and we had a visitor at the cottage and in discussing the game the question, "How many hands, on an average, does a person have to play to 'get out'?" came up. I think someone around the table had "got out" the first time and then again the first time, while another had "just played and played and never 'got out'!" I did some computing, taking into consideration the average number of cards one got out when he did not get entirely "out," and I said, I believe, that Canfield could not have made a profit if his patrons "got out" oftener than once every eleven hands, if the game was played as we were playing it. That was what started me; I wanted to see about it.

Now, in any game or in any business or in any profession the personal equation has to be taken into consideration. One person plays a game better than another. If the game is that of throwing a ball through a hole in a fence you cannot stand John Jones up and let him throw the ball at the hole a thousand times and then say, as a true fact, "A baseball can be thrown through a one-foot hole exactly one hundred times out of a thousand throws" just because that was what John Jones did. Sam Smith might throw the same ball through the same hole two hundred times out of a thousand, or only fifty times. You'd have to choose a hundred average men and let each throw the ball a thousand times before you got anything like a true average that would represent the ability of men in general in throwing a baseball through a hole in a fence. This is the sort of thing statisticians are doing all the time, and I hope they enjoy it.

Well, the first time I sat down to try out this Canfield idea of mine I suppose I was too eager to get going and get finished. I shuffled the cards thoroughly and mixed them up until the red spots began to be pink and the black spots were gray, and then went at it. I laid down the cards according to rule and began to play -- and I didn't "get out" that first time. Neither did I "get out" the second time. I had to play twenty-four hands before I did "get out."

The next time I tried it, I "got out" the second time I shuffled the cards.

That meant, as you can see, that I played twenty-six hands in getting out twice, and the average was thirteen. So I tried it again and I played eighteen hands before I got out. That made my total hands played forty-four and my average fourteen and two-thirds. Then I got out with the second hand; then with the fourth; then with the eleventh; with the fourth again, and then with the eighteenth. From then on the number of hands I had to play varied in much the same way; now and then I "got out" the first time I played a hand; twice I had to play thirty-seven hands before I "got out." When I had played two hundred and seventy-five hands my average was just about thirteen -- the same as when I had played my first twenty-six hands. When I had played four hundred and ninety-six hands my average was still just about thirteen. If I had played a million hands I suppose my average would have been just about the same -- thirteen.

There was one thing about this that struck me as very interesting. When I had played my first series of hands, and had "got out" the first time, my average was twenty-four, because I had played twenty-four hands. The next time I "got out" in two hands. This brought my average down with a whoop, because twenty-four plus two is twenty-six, and half of that is thirteen. By doing a "two" that early in the series I reduced my average a full eleven points, from twenty-four down to thirteen. It was mighty well worth while doing a "two" about then. But when I had played four hundred and forty-two hands my average was exactly thirteen, and the next time I "got out" in two again. Do you think this benefited me any eleven points in my average? No, indeed! It helped me only a trifle; it only reduced my average from thirteen to twelve and twenty-four thirty-fifths.

Here is why:

Played 24 times. Out 1 time. Average 24. (24 divided by 1)

Played 26 times. Out 2 times. Average 13. (26 divided by 2)

But when I had played four hundred and forty-two hands, doing an eighteen in order to "get out," it was my thirty-fourth time of "getting out," or--

Played 442 times. Out 34 times. Average 13. (442 divided by 34)

I then played again and "got out" with the second hand I played, and all the good it did me was this:

Played 444 times. Out 35 times. Average 12 24/32. (444 divided by 35)

This seems to mean to me that when a man gets along to a point where his average is made up of a great many things he has done, it does not do him much good to have one or two strokes of extra good luck. The figure he has to divide it by gets to be too big. In order to "make good" in the end a man has to try just about thirty times as hard after he has had thirty failures as he need try when he is just beginning; the average is against him. If a man has made one failure and one success his average is .500; if he then buckles down hard and makes his next attempt a success he has a success average of .666. If, on the other hand, he fools along until he has one hundred failures and one hundred successes and his average is .500 and he then makes one more success it does not mean much, because it only boosts his average to .500 1/2. When he is that far along he will have to have one hundred successes in succession, and no failures, to climb up to that .666 average.

This figures out the same way whether you compute it in well-spent days and wasted days, in things well done and things ill done, or in playing a fool game with a pack of playing cards. The time to begin getting your average right is right away and just now and the soonest possible. Every weak wallop and careless job I let get away from me means I'll have to do something almost impossibly perfect later on, or I'm a fizzle in the long run.

There is an old story about the clothing merchant who came forward in his store rubbing his hands together and grinning at the customer who had just entered. He showed the man a suit of clothes but the customer said he thought it was too high in price.

"Listen to the man!" exclaimed the clothier. "He says such a suit is too high when I make him a price of twelluf dollars on it yet! Such a suit you could not get anywhere for thirty dollars, my friend. This is the cheapest place in town; nothing we sell except for less than cost."

"My goodness!" exclaimed the customer. "I don't see how you can make any money if you sell everything for less than cost!"

"Listen, my friend; I tell you a secret," said the clothier confidentially; "we couldn't except we sell such big quantities."

Nobody can get rich selling everything below cost all the time; nobody can wind up with a good average of success if he lets the failures pile up against him until not even a ton of T.N.T. will chip a fleck off his average.

I can say these things because I am one of the worst sinners in the lot in all these things. I hold the diamond-studded championship belt for waiting until tomorrow to get at the big job and then putting off the big job until day after tomorrow while I do something just about as important as training a caterpillar to walk backwards on a clothes brush. If a man ever did train a caterpillar to do that it would not profit him much; just about when he had the caterpillar trained it would turn into a butterfly and fly away from him.

I have sometimes wondered just how much the actual worthwhile work a man does would amount to if it could be figured down to hours and minutes. I believe the genuinely creative work of even the greatest men would come to an amazingly small number of minutes per day when averaged over a year or two. I believe it is so small that if the average man would give an average of five additional minutes a day to his real problems he would class among the giants. Go back to those first fifty-four hands of Canfield I have spoken of for a moment. It is a most trivial instance of what I mean, but it does show what I mean.

You know how solitaire is played: the cards are laid out, mostly face down, and certain moves are possible. If you make the right move you have a chance to win; if you make a wrong move you can't win. I played twenty-four hands; if chance was not against me and I played the hands perfectly I might have "got out" in any of those hands. If I had not "got out" the first time I might have "got out" the second time, or the tenth time. If I had not been too eager, and if I had taken a second or two more in studying possibilities before I moved each card, my average for the first two times "out" might have been two instead of thirteen.

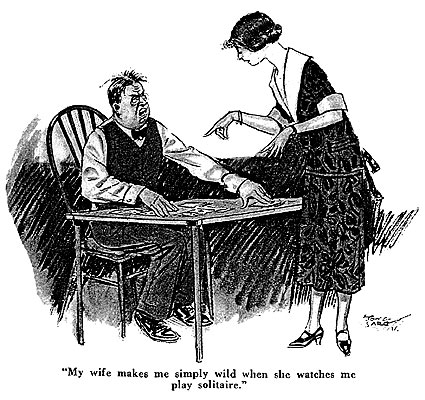

Nearly everyone has sat opposite some card player, or watched some solitaire player, who made one mistake after another that you could see. My wife makes me simply wild when she watches me play solitaire; she says "You can put that six on the five," and so I can; she says "Why don't you play your ten on the nine?" and the reason is I did not see it; she says "Don't you want to use that seven?" when, goodness knows! I would want to use the seven if I saw it. That's one of my "human equations" and one reason why my batting average is as low as it is. I'm like old Endicott's colt that couldn't wait for the corn to get ripe and jumped the fence into the knee-high corn and ate itself so full it swelled up like a giant-size football and died of colic.

You may have read the books written by Nansen or Amundsen or Steffanson relating their Arctic and Antarctic explorations. All three came back alive; all three were notable for the thought they gave their plans and outfits before starting. Nansen gave as much thought to the designing of the "Fram," which was to be frozen in the polar ice and travel the arctic currents, as Shakespeare gave to his plays before writing them, and yet the planning of the "Fram" took but a few hours as compared with the years the vessel was wedged in the ice up north there as planned. Nansen planned carefully and all his men came home alive; if Nansen had been one of us sketchy fellows and had cut his planning short by an hour or two he and his whole company might have perished up yonder in polar bear precincts.

I have swung around New York and other places quite a few years now and I have met quite a few thousand men and I am more and more impressed by what seems to me to be the fact that the men who accomplish the big things are apt to be the men who take time to mature their plans and acts before they put them into operation.

There are some occasions when frantic haste is not to be sneered at, I will admit. If you happen to be standing on a street crossing when a high-powered automobile came around the corner headed right at you at forty miles an hour I do not advise you to stand there waiting for anything to ripen. It is a good time to jump, and to jump as far, wide, and handsome as you can. If, on the other hand, you happen to be the man who is contemplating going around that corner at forty miles an hour in the high-powered automobile, it might be as well to draw up at the side of the road and think about it for a day or two. It might be that after you had sat there for a week you might find it unnecessary to go around that corner at all, or you might cool down and decide that excellent results might come from rounding the corner at four miles an hour, tooting the horn violently meanwhile. In any event a contemplative pause of an hour or so would give the man on the crossing time to go elsewhere and you would be saved the work of scraping him off the radiator.

Even when in justifiable haste, a man can usually make better time by using less speed and more brains. Nine out of ten men who sit in the justice court two long hours, waiting for the judge to get back from lunch and fine them twenty-five dollars, are the fellows who were in such a hurry that they tried to save two minutes in a ten-mile run by speeding up. By the time the clerk of the court has entered the officer's complaint against the speeder and the trial is about to begin, some slower but more thoughtful man has reached his destination, completed his business, and is taking home the money in a brown leather valise.

The giants in business, in the professions, in the arts, and in the sciences, are the slower, more serene, more time-taking men. The hasty and unduly impatient man is apt to be the flash in the pan. The higher you look the more apt you are to see this quality of being willing to wait until the time is ripe and the plan is mature. There is an amazing appearance of placidity in the great men of all times. Lincoln might have posed as the model for Rodin's "Thinker"; you inevitably think of Washington as deliberate; many of our great financiers seem almost to deserve the adjective "heavy"; there is no profit in flopping like a minnow on a hot rock -- the minnow bounces around a lot but it does not last long. When Steffanson, MacMillan, and others found their lives depending on securing game in the far north they spent hours stalking the caribou before they shot, and they usually made their kill; it was when some member of a party was too hasty that the game got away and a hungry night was spent. On the Polar ice Steffanson spent hours studying the habits of the seal; he made a table showing the minutes a seal slept between its watchful waking moments; he learned just how long he could crawl across the ice toward the sea while it slept, and he did this so that he might be flat on the ice and motionless, like another seal, when the seal prey he stalked awoke and looked around. Steffanson got his seals when even the Eskimos could not get them. He says the white man can live off the land in the Eskimos' own country much better than the Eskimo himself can, because the white man has a better brain. But a better brain is of no use to a man unless he uses it before he undertakes the job he has in hand. If he makes a sort of ivory jug of his cranium and corks his brain up in it, and lets his brain repose there like a midwinter possum curled up in a hollow log, his brain is not going to help him much. He might as well have a chunk of Swiss cheese under his hat.

When I was young -- young enough to resemble a chicken that has just popped out of the shell and that is looking around with interest and surprise and trying to get acquainted with the world it has been so unceremoniously shelled into -- I saw all the men and women as complete and ready-made pieces of human waxworks. So did you when you were that young. You became aware on a certain day of, let us say, Xerxes P. Cranch and Giffus L. Pilkey. Of these two men Xerxes P. Cranch ran the dry goods store on the east side of Main Street and Giffus L. Pilkey was put down in the town directory as the owner of the dry goods store on the west side of Main Street. The store of Xerxes P. Cranch, when you first knew it, was sixty by one hundred and twenty and had two show-windows with a door between them, and the store of Giffus P. Pilkey was exactly like it in those particulars; in other ways the stores were not alike. Neither were the men alike.

When "Zerk" Cranch went out on the street he was almost as well worth seeing as a complete circus parade with ten elephants. His felt hat -- it was a derby later on -- looked as if it was made of silk fibers pressed into felt by loving hands and ironed by slaves. He wore it one sixteenth of an inch off the level to match his smile and his smile was the sort that includes the eyes. He looked as we would say now, like a million dollars, and he bulged neatly in front but not a great deal. In his vest pocket he had the best watch that Mawn (The Honest Jeweler) ever sold.

"Zerk" Cranch, when he left his store, usually walked to the bank and there left a wad of money which the cashier entered in the Cranch passbook and usually the bank president called out "Wait a minute, Zerk!" and got into his coat and went on down to the post office with Cranch. They stood in the post office lobby while the mail was being sorted, and the other important men of your town and my town -- whichever it was -- joined them and talked of this and that. The mayor (who was the leading dentist), Judge Olvaney of the County Court, Norbert Vindermoor who was retired, and Meefus Diggs, the wholesale grocer, were some of those who joined the group and talked of important matters such as whether it looked like rain and why the 9:08 fast train from Chicago was twenty minutes late last night.

That Xerxes P. Cranch, as you first saw and knew him, seemed to you a completed and static human being; he must have been always like that. And Giffus L. Pilkey seemed to you an equally immutable and permanent being, but of a different sort. "Tuttut" Pilkey was what they called Pilkey, because he was always saying "Tut! tut!" in an annoyed and helpless manner. Although he wore clothes quite the same as those other men wore, "Tuttut" Pilkey always seemed, when on the street, to have come forth hastily in carpet slippers and a bathrobe. He always suggested some shameful plant, grown in a cellar, and for a moment scurrying out into the sunshine which annoyed him.

When "Tuttut" went to the bank it was in a rush and his coat collar was usually turned under at one side at least, and he had the air of a man who had received a warning that if the Billings-Carter draft was not met by three o'clock it would be protested. One of our memories of him is that he was frequently being let out of the bank three or four minutes after closing time, probably because he had been able to raise the money to meet that draft only at the last possible minute. When he went to the post office it was after the mail was distributed and he slithered in, opened the box and got his mail, and slithered out again like a frightened fox gliding along the side of a chicken coop.

The difference between the stores of Xerxes Cranch and Giffus Pilkey you remember well. It was not that Giffus Pilkey was always just out of number sixty white cotton thread but expecting some tomorrow, while Xerxes Cranch could always match the exact shade of the sample of fabric your mother sent you to match and could do it with thread of either number fifty, sixty, or seventy size; it was that the two show windows of the Pilkey shop always looked sick and hungry while those of the Cranch shop looked plethoric and happy; it was further that the floor above Pilkey's store was Lawyer Burton's offices, and the floor above that was where the Heddleburys lived, while the Cranch Building -- see the name on the zinc cornice -- was Cranch store all the way to the roof.

Young as you and I were we knew that Cranch was a success and Pilkey was a failure. We knew that Cranch was not only a business success but that he was happy, contented, and satisfied with life; we knew that Pilkey was sour and annoyed and nervous and fretful. We knew there was as much difference between the two men as between the equator and the pole -- anyone could see that -- but we accepted the two men as ready-made specimens and examples, and if we thought anything about them it was that they had always been just about as they were. Cranch, we thought, had always been successful and Pilkey had always been a fizzle.

The truth about most men, as it was the truth about Xerxes P. Cranch and Giffus L. Pilkey, is that they are and were the result of daily averages of brain-use. You can take two stores, side by side, and put a Pilkey in one with fifty thousand dollars, and put a Cranch in the other with seven thousand dollars in cash and an eleven-thousand-dollar mortgage on his late father's farm, and in twenty years Cranch will be Cranch and Pilkey will be looking glumly at a huge pile of unpaid bills and duns and wondering if he had better go into the hands of a receiver before or after Christmas. By the time you are a middle-aged gentleman with fallen arches or a golf score just breaking one hundred you have lived alongside several Cranches and Pilkeys and you don't have to be told anything about them; you have seen Cranch making a little better average every day than Pilkey makes, and you know why Cranch is Cranch and Pilkey is Pilkey. You are apt to say, if you mistreat the English language as I do: "Why, that poor prune Pilkey never could succeed; he has no head on him; he goes off half-cocked!"

In the long run -- and that's what a man's life is, believe me! -- the winner is not the hasty hustler but the patient considerer. The successful man considers one thing and plans it rightly while the other fellow is rushing to do ten things and doing all ten of them the wrong way.