|

|

from Collier's

Safety First

by Ellis Parker ButlerIn and around Black Bend, which is the great oil-boom town, Joe Waters was called a careful man, and if he had not been worth considerably over a million dollars -- increasing, it was said, at the rate of a good hundred thousand a month at least -- some less pleasant term might have been used. He had an "office" in the new First National Bank Building, but the three clerks had very little to do. They kept track of the money due him on account of the leases of the small subdivisions of the quarter section that had once been his farm, but which was now a forest of oil derricks, and they deposited the checks to his account in the bank when they came in, and in a general way they looked after his investments, but Joe Waters was so cautious that he invested in nothing but Liberty Bonds. Most of the time Joe's clerks had nothing to do but sit around the office and read the newspapers or do embroidery. Miss Cleaver, who was the head clerk, did the embroidery, and Rex Filson and Sam Miller read the newspapers.

Joe Waters' idea seemed to be that his money and affairs were safer if he had three to look after them, and perhaps he was right. Defalcations and dishonesties did not enter into his calculations at all -- he had faith in his clerks -- but he could not write very well and had only rudimentary knowledge of arithmetic and he felt that if one clerk happened to make a mistake in figures or entries one of the other two would probably notice it and correct it. He had made a mistake once and he believed in playing safe. So day after day and week after week his clerks idled in his office while Joe enjoyed his wealth in his own way, which was mainly riding around the country in his car.

The years had made Joe rather stout, and in cool weather he was rather a sight in his automobile. He wore a coonskin coat, but it looked as if it had grown on a porcupine, the fur being unusually bulky and bristly, and when Joe sat in his little car he practically filled both seats. He drove sitting bolt upright, never proceeding over fifteen miles an hour and usually traveling much slower, grasping the steering wheel tightly with both hands.

The slow pace or his great cautiousness caused him to "drive" more than even the most inexperienced learners, although he had had a car for years. He was continually pulling the wheel one way or the other, and all this with the utmost concentration. When a car passed he would go almost into the ditch; even when the road was clear he drove close to one side.

At railway crossings Joe was particularly careful. He stopped his car dead still, climbed out, walked to the middle of the tracks and looked one way and then the other. In cold weather he wore a fur cap with ear tabs that tied under his chin, and he would untie these and raise them and listen for a train. If all was clear and no train within sight or hearing, he would climb into his car and cross the track. When across he would stop the car again, set his brakes firmly, and tie the strings of his ear tabs. He had never been killed at a railway crossing, and it was pretty safe to bet that he never would be.

One afternoon Joe Waters had been visiting his office and was buttoning the frogs of his enormous overcoat preparatory to going out again when the door opened and a young man, a slender, eager-looking boy of some fourteen years, opened the door and entered. The boy took off his hat immediately, and stood holding it.

"Well, son?" Joe Waters queried.

"Why, now," the boy said nervously, "I want a -- I mean, I thought maybe -- I mean, I'm looking for a job."

Joe Waters continued to button his overcoat, pulling it tight across his large front so that the loops might reach to the buttons.

"Well, now, son," he said, "I'm afraid you've come to the wrong place for a job. Seems as if I got all the hands I want right now."

"I've been through second year of high school," the boy said, as if that might be an inducement. "I've got to get a job, I guess."

"I'm right down sorry," said Joe Waters. "It ain't as if I wouldn't like to hire you if I needed help." The boy said, "Yes, sir," and turned to go, but something in his face brought a memory to the surface of Joe Waters' mind.

"What's your name, son?" he asked.

"Tildock," the boy answered. "William Joseph Tildock."

"Hum!" said Joe Waters. He pulled at his chin, where he had no beard, and frowned a little. He unbuttoned his overcoat and let it fall open, and went to his own desk. From a drawer he took a blank note, ". . . after date I promise to pay --" and carefully scrawled in an amount and signed his name.

"Now, son," he said and beckoned the boy to come to the desk, "here I've made out a note for two hundred dollars, payable to John Smith -- whoever he is -- payable one year from date, with interest at eight per cent. All right! Now this John Smith, he don't step up and pay this note when the year blows by. He don't pay it for three years, two months and seven days. How much interest does he have to pay me?"

He handed the boy the note and arose, signifying that the boy might sit there and use the pad and pencil on the desk, and the boy seated himself. He sat on the edge of the chair, leaning forward, and picked up the pencil, but he looked at the note again and then into Joe Waters' face.

"If you made out the note this way," he said, "he wouldn't have to pay you much, I guess. It only says two dollars and interest."

"Does, hey?" said Joe Waters, taking the note and tearing it into scraps. "Sort of careless of me, making it out that way. A man's liable to lose a lot of money if he gets careless like that. A man that gets careless that way ought to have somebody to check up on him all the time. What did you have in mind for wages, son?"

"I thought if I could get twelve dollars a week," the boy said diffidently, "I could pay board and help Ma some. We been having a sort of hard time, crops going back on us right along."

"Your ma's name Tildock?" Joe Waters asked.

"Yes, sir."

"Whereabouts is this farm you're telling about?"

"Back in Colter County, over toward Nord."

"Yeh? Well, Miss Cleaver, you start this young lad in at a hundred a month -- say twenty-five a week, huh? -- and see if you can find something for him to do once in a while."

"But, Mr. Waters," Miss Cleaver protested, "we don't need anyone. There's not enough to keep us busy an hour a day, without him."

"No tellin'," said Joe Waters, buttoning his overcoat again. "I got to be watched mighty close, a careless feller like me. Liable to write a wrong figger any time, come I get excited or somethin'. Cost me lot of money, maybe, if I ain't watched close. You feel so, don't you?"

"No, I do not!" declared Miss Cleaver. "I think. it is mere foolishness hiring another clerk."

"Oh, well, if you feel that way!" said Joe Waters, grinning at her. "That's another breed of cats. If you feel that way, I guess we might as well start the young feller in at thirty dollars a week, 'stead of twenty-five. Well, I got to be goin'. Be back sometime, like as not." He went out, closing the door, and Miss Cleaver laughed sardonically. She looked at the young man as if she did not know what to think of him; probably she was thinking she did not know what to give him to do.

"I don't want to be in the way," young Tildock said hesitantly. "If you don't want me here --"

"Of course we want you here!" she said. "If Joe wants you, we want you. Take off your hat and sit down while I think up something for you to do."

Joe Waters opened the door and put his head inside. "Say," he said to his new employee, "you said your name was Tildock?"

"Yes, sir," young Tildock replied.

"You said your ma was dead?"

"No, sir," Tildock answered. "My mother's alive; she's running the farm -- it's my father is dead."

"Now, hear that!" exclaimed Joe Waters. "How long has he been dead, son?"

"Four years," the young fellow answered. "Four years last June."

"Now, ain't that too bad!" said Joe Waters, and he turned his face in Miss Cleaver's direction. "Miss Cleaver," he said, "this poor young man ain't got no pa; you better pay him thirty-five dollars a week from now on," and with that he went out again, closing the door carefully.

"He must like the way you're doing your work," Miss Cleaver said sarcastically.

"I guess he's just good-hearted," said young Tildock modestly.

Joe Waters went down to the street and took a heavy blanket from the hood of his car, cranked the car vigorously -- it was that vintage -- and when the motor was palpitating heartily climbed in. Grasping the wheel with a death grip, he steered carefully through the streets and out of town by the road that led in the general direction of Colter County. In his pocket he had a reasonable wad of money; there were hotels in some of the small towns through which he expected to pass, and a few days and nights meant nothing to him.

It had been almost fourteen years since Joe Waters had been in Colter County, and his last night there had been a snowy one -- a miserably cold, blowy and snowy night. It had been new country then and mighty poor country at that, and it was no better now. Some of the poorest farmland in the prairie country it was and is, and the quarter section Joe Waters had preempted had been about the worst of all. On this quarter section he had built himself a fairly decent pine shack and a sod stable for his animals -- one cow and two horses. There was also a rough-and-ready bin for his corn, but there was no sale for corn and he burned it as fuel.

Over in one corner of the shack he had a pine board held up by two pine boxes, and this was his table; in another corner was his bed, and a good enough bed it was, being a real bed with a spring mattress. A box nailed to the wall served as food and dish closet; the floor was dirt; around the base of the house, outside, the sod he had plowed up as a firebreak was now piled to keep out the cold, and inside the house the cracks were hidden by strips of tar paper, tacked on. On top of the food box was a flat lamp, but the lamp he used mostly was a taller one on the plank table. Under the food box Joe Waters always kept a pail of water; this was not only for drinking purposes, but for use in case of fire, for he was a careful man, not at all eager to take chances.

On this last night he spent in Colter County Joe Waters had fed his stock and milked the cow and seen that the door of the sod stable was well closed, for a blizzard threatened. It might come and it might not, but a feel of it was in the air, and Joe Waters did not like to take chances. After his supper he sat a while playing old tunes on a rickety accordion, and once or twice, when the songs happened to be romantic in tone, he looked out of his one window in the direction of the Tildocks' shanty across there on the opposite quarter section. A light burned in the Tildocks' window, a yellow spot in the distance, and as Joe Waters pumped the accordion he had a thought now and then of Tildock's wife. Tildock's wife was a mighty fine looking lady, and no mistake.

Joe Waters did not covet Tildock's wife; he was too careful-going to covet anybody's wife. He just sort of liked her, as he would have said. A bachelor fellow, out there on the prairies all alone, with most of the women immigrant Swedes and such like, it was a pleasure to have a woman like Tildock's wife say a kindly word to you now and then and to talk about things back East with once in a while. Not too much talk, and not too blamed friendly, but just now and then and occasionally, as might happen to anybody with any neighbor woman. Nothing, by a long shot, to rouse up Bill Tildock.

Presently Joe Waters folded the accordion into its smallest compass, took off all his clothes but his underclothes, blew out the light, and got into bed.

Along in the night some time -- it was just after twelve, but he did not know that -- Joe Waters was doubly awakened. First he thought the ache in his knees had awakened him, because the weather had turned bitter cold and the fire in the stove had burned out and he had drawn his knees almost to his chin, the blanket having come out at the foot of the bed, but a moment later the knocking on his door sounded again and he sat bolt upright, swinging his feet to the floor.

"Who's there?" he called.

"It's me -- Emmy Tildock. Let me in," came the answer. It was then that Joe Waters became aware that the snow -- fine, hard snow like sand -- was beating against his window, that the wind was blowing steadily and hard.

"Just a minute; I got to get my pants on," he called, and he went to the lamp and lighted it and threw ears of corn in the stove, opening the damper, and slid into his trousers, buttoning them hastily and drawing his belt close around his waist.

"Please, Joe, let me in; I'm freezing," Emmy Tildock cried.

"Right away in a minute now, ma'am," Joe Waters answered, and glanced around the interior of the shack. He knew with fair certainty what had happened; what had driven Emmy here. Bill Tildock was on another of his raw-liquor rampages, raising hell over yonder, crazy drunk.

"Bill on one of them rampages again?" he called.

"Yes, I was afraid for the baby; I was afraid he'd kill us. Let me in, Joe; we're like to freeze to death out here."

So they were, for that matter, and Joe knew it. As likely as not she had come -- such fools women are! -- half clad, perhaps in her nightgown and a shawl and barefooted. They'll do such things for their babies, women will.

"And at that," Joe Waters thought, "maybe she'd be glad enough to get shut of Bill Tildock, any shape or manner. Only --"

He was a careful man, Joe Waters was. It wasn't by any means only that Bill Tildock was a violent sort of man who would think nothing of coming over in the morning with a shotgun to make mean trouble for his wife and any man with whom she had been shut up in a lone cabin. It was what folks would think too. Things such as that Bill Tildock maybe had a good reason to chase his wife out, because look where she went as straight as an arrow as soon as she had a shred of an excuse -- right straight to Joe Waters' shack!

So Joe Waters opened the door.

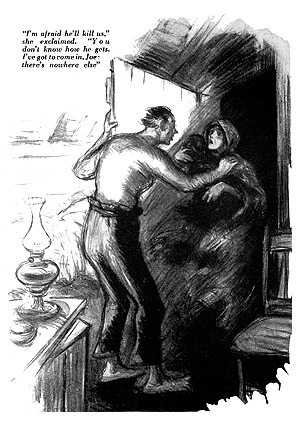

In the lamplight, with the shawl over her head and her dress flapping in the keen cold wind and the baby held close to her bosom, Emmy Tildock was like a Madonna standing there in the storm, her eyes raised to Joe in mournful-eyed supplication. She bent forward to enter and Joe Waters put a hand against her shoulder.

"I'm sort of afraid you can't come in here, Emmy," he said. "You'd ought to go back home."

"I can't! I can't!" she exclaimed. "I'm afraid he'll kill us. He's crazy mad, Joe. You don't know how he gets -- so jealous mad when he's drunk. I've got to come in, Joe; there's nowhere else."

There wasn't either; no other house for miles.

"I guess you'd better not come in," Joe repeated. "It ain't going to look right, somehow, when Bill finds you here in the morning. It ain't going to look right for neither of us. It's going to look bad, me and you here all night alone, and you runnin' off from him this way, like you'd come straight here. Now, you ought to see that, Emmy."

"But what can I do?" she cried. "What can I do?"

"Well, now, how about this?" Joe asked. "What if I was to hitch up the team for you and you was to drive on into Nord? You and the baby, huh? And, come morning, I don't know a word about it. -'You seen my wife?' Bill says to me. 'No,' I says, 'I ain't seen her.' 'She cut away durin' the night,' he says. 'Well, I don't know nothin' about it; I slep' sound all night,' I says. 'But your team and wagon is gone, Joe,' he says. 'By dad, that's so!' I says. 'How do you account for it?' he says. 'She must have snuck over and hitched up,' I says, 'and drove to Nord.' How'd that do, Emmy?"

"But I can't do that," she replied, her eyes appealing to him. "With my baby? He'd die in the cold, Joe Waters. And I would die too; I'm not dressed for it. Please let me in!"

The hard snow stung the hand he was holding against her shoulder and already his fingers were stiff with the cold. She saw he was not relenting from his first decision, and she began to cry weakly, bending her head over the baby, crying like a child that is lost. Joe Waters frowned.

"Say, look here, Emmy," he said suddenly, "I ain't goin' to get you in bad with Bill Tildock, and I ain't goin' to get myself in bad with him neither. I ain't goin' to let you sleep in this shack with nobody but me, and have Bill Tildock come rarin' down upon me in the mornin', shootin' and killin'. He's pretty near got it in for me now, and I don't want no more of it, but I'll tell you what's fair and square. I'll sell you my quarter section and get out."

"Sell it?" she queried, not understanding.

"Sell it!" he repeated. "If you got to come in and spend the night, I'll sell it and clear out for good and all, lock, stock and barrel. Then nobody won't have no kick whatsoever. Fair bargain and trade. You pay me and it's yours."

"But how can I pay you?" she asked.

"I'll take your note," said Joe Waters. "Say two hundred dollars, pay it off when you're a mind to, eight per cent interest from the end of the first year. And she's easy worth three hundred, Emmy. What say?"

"I must come in! I must get Baby out of the cold!"

"Well, you just wait there a minute more," Joe Waters said, "and I'll fetch you the note all ready to sign, and I'll get out and leave you have the shack and the whole caboodle, cow and all. Just you wait one minute --"

He closed the door and hurried into his remaining garments and put his fur cap on his head. On a scrap of paper he scribbled the note hastily, and in little more than the minute he opened the door again. Her hand was so cold she could hardly grasp the pencil, but she scrawled her name somehow, and Joe Waters stepped out into the storm. He threw up his arm to shield his face as the cutting snow struck it, and Emmy Tildock stepped across the threshold. It was Joe who closed the door.

As he fought his way to the sod stable he felt glad that there was fresh milk in the shack and that there was a good supply of corn in the wood box by the stove. He hitched his team and clambered into the wagon seat, wrapping the buffalo robe well around his legs, and drove across the field toward Nord. He was through with Colter County for good and all. At Nord he stopped for dinner and to have his team fed, and bought a pair of warmer mittens and drove on. He was not dissatisfied to be out of Colter County and to put distance between himself and Bill Tildock and his jealousy. He was not even sorry to put distance between himself and Emmy Tildock. He drove all that day and the next, and at night inquired about land. Two more days he drove and reached Black Bend, with snow two feet deep on the level, and here found new land to be preempted. It was only then he felt his journey was ended, and it was here he smoothed out Emmy Tildock's crumpled note.

"Well, I'll be durned!" he exclaimed as he gazed at the crumpled paper, for in his haste he had written, not "two hundred dollars," but "two dollars." "And I threw in the cow!" he grinned to himself. "That shows a man's got to be careful."

In the years that followed he thought of Emmy Tildock more than once. He thought of her when he hauled huge wagonloads of corn to nearby Black Bend, where a railway was so handy and corn had a good market. He thought of her when he stood on the rich black soil of his new farm, looking up at corn that towered above his head, and thought of the nearly barren acres of Colter County, the acres Emmy had driven him to sell for nothing. He thought of her when the first oil well started the Black Bend boom and men crowded to him waving money in his face, begging him for lease rights. He thought of her gratefully as the royalty checks came piling in.

And now Joe Waters, not at all a hero, stopped his car carefully before the unfenced dooryard of the Tildock farmhouse. He climbed carefully to the ground and walked to the front door and knocked. As he waited he untied the ear tabs of his cap and tucked them inside the cap, and cleared his throat twice. He heard someone unlock the door and pull at the knob, for the door stuck at the bottom. He kicked it with his toe in the way of friendly assistance, and the door opened and Emmy Tildock was standing there. For a moment she gazed at him as one might at a face seen indistinctly through a mist, and then she spoke.

"Well, if it ain't Joe Waters!" she exclaimed.

"Emmy!" he said and put out his hand, and she took it, and he knew by the handclasp and the light in her eyes that everything was most likely to be all right. "Emmy!" he said again and then took her other hand and said:

"I'll be right in in a minute; just want to toss a blanket over the radiator -- if a man ain't careful, she's liable to freeze."

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 3:14:55am USA Central